…in light of the recent extraterrestrial incursion, this council of nations has convened to approve the activation of the XCOM project. You have been chosen to lead this initiative to oversee our first and last line of defense. Your efforts will have considerable influence on this planet’s future. We urge you to keep that in mind as you proceed. Good luck, Commander.

So begins XCOM: Enemy Unknown, a 2012 turn-based strategy game in which the player takes on the role of the Commander of XCOM—short for “Extraterrestrial Combat Unit”—an international paramilitary organization responsible for defending Earth against an invading extraterrestrial force. To do so, the player must command and lead multiple teams of soldiers from 29 different nations to defend against this new threat while simultaneously managing and supervising the more bureaucratic tasks of research and development, communications, construction, and funding and expenditures. XCOM is supported and funded by “The Council”, a UN-like entity comprised of 16 nations from around the world, and the Commander must complete their tasks while trying to keep these nations appeased by reducing their “panic,” a measure inversely related to the amount of satellite, aerial defense, ground force protection, and services afforded to a given country. In the tutorial mission, “Devil’s Moon,” the player is introduced to XCOM’s Chief Scientist Dr. Vahlen, whose native fluency in German allows the Commander to attempt to speak to a mind-controlled, alien-enslaved German recon team before witnessing their own ground team of four XCOM rookies—an American, a Russian, a Japanese soldier, and an Argentinian—overrun by the enemy. Upon returning to the base, the player views a short exchange between Central Officer Bradford, Chief Scientist Dr. Vahlen, and Lead Engineer Dr. Shen, that concludes with Vahlen’s final remark to Shen, “…I’d say our work is cut out for us, Doctor.” The racial and national diversity of the characters, and the narrative emphasis on their working together as citizens of Earth thus inform the player that even in the face of the planet’s annihilation, working towards unification across national, ethnic, racial, and linguistic differences is key to humanity’s survival and proliferation. The defense of Earth is a distinctly multinational, human-oriented endeavor.

This emphasis on multinational collaboration, however, is absent from the game’s recent board game adaptation, XCOM: The Board Game. In fact, references to individual nations at all are replaced with more generic identifiers; in lieu of The Council’s funding countries, the players must concern themselves with panicked continents, and instead of soldiers being recruited from various nations, all soldiers come from a single, a-geographic “recruitment pool”. Even Dr. Vahlen and her XCOM peers Dr. Shen and CO Bradford—presumably Taiwanese and American, respectively—are absent, as the game’s players themselves now act as the bureaucratic managers of varying resources for XCOM. Without these characters, the board game version is also more heavily focused on the administrative functions of the game, as players must make rash decisions that are bound to a strict budget and even stricter countdown clock, oftentimes negatively impacting their peers as they cooperatively yet self-interestedly vie for strategic monetary support against the incoming alien onslaught. If the player is reminded of the multinational efforts needed to deter the alien invasion in the XCOM: Enemy Unknown, XCOM: The Board Game instead reminds players that all organizational labor, even in the face of apocalypse, is formally institutional, intimately tied to capital, and dehumanizingly bureaucratic.

Ostensibly, XCOM the video game and XCOM: The Board Game are games “about” the same thing: “an escalating alien invasion” and “the tension and uncertainty of a desperate war against an unknown foe.” Various scholars in game studies invite us to explore, however, the ways in which games produce meaning in ways particular to the gamic form, from Ian Bogost’s concept of “procedural rhetoric,” the persuasive power of algorithmic and formal processes, to Alexander Galloway’s approach to informatic control critique over the ideological. Gonzalo Frasca’s oft-cited “Simulation versus Narrative” serves as prime evidence of the work to establish games as producing meaning not through traditionally representative features, as would normally be accounted for by traditional literary theory. And fundamentally, Espen Aarseth’s notion of games as “ergodic,” requiring “non-trivial effort to traverse the text,” highlights the importance of examining the gamic form as interpolating and hailing the player-as-subject differently than other forms of media. To this end, game studies has historically privileged the mechanical and rule-based features of games as the foundational site of meaning-making and subject construction.

The notable differences in how the video games and the board game treat race and nation, however, invite us to explore their functional roles in facilitating and producing play, despite neither being accounted for fully in the process- and rule-based structures of the games. And scholars such as Adrienne Shaw, Shira Chess, and many contributors to Analog Game Studies have articulated the need to look beyond the mechanical and algorithmic features of games, particularly around issues of race, gender, and sexuality. Based on play sessions of XCOM: Enemy Unknown and Within and XCOM The Board Game, this paper suggests that games scholarship, in order to accurately address nation and race, must grapple directly with the affective role of race and nation, despite often being ignored in more formal and mechanical accounts of games and game design. I take the video game and the board game as interesting comparative cases, given their distinct similarities yet glaring differences, to explore the means by which scholars can explore more affective dimensions of play as inherently built in to the structures of games themselves. Nodding at sociological scholarship on organizations and culture, I argue that games operate beyond their calculable, formal rule sets and employ “affective structuring” informally to facilitate play through cueing and priming of certain emotional responses and the interpolation of certain relational subject positions in players. Given our contemporary socio-cultural and geo-political landscape, I argue that such affective structuring in games is imbued with and built upon raced concepts and ideas. Even an absence of racial demarcations signals certain modes of race logics, from the deracialized modern bureaucratic logic of XCOM: The Board Game to the liberal multiculturalism of XCOM: Enemy Within. This suggests a necessary rethinking of games as a combination of formal rules and informal affective structuring, wherein race and nation figure largely in the organization of human-player activity.

The Video Game

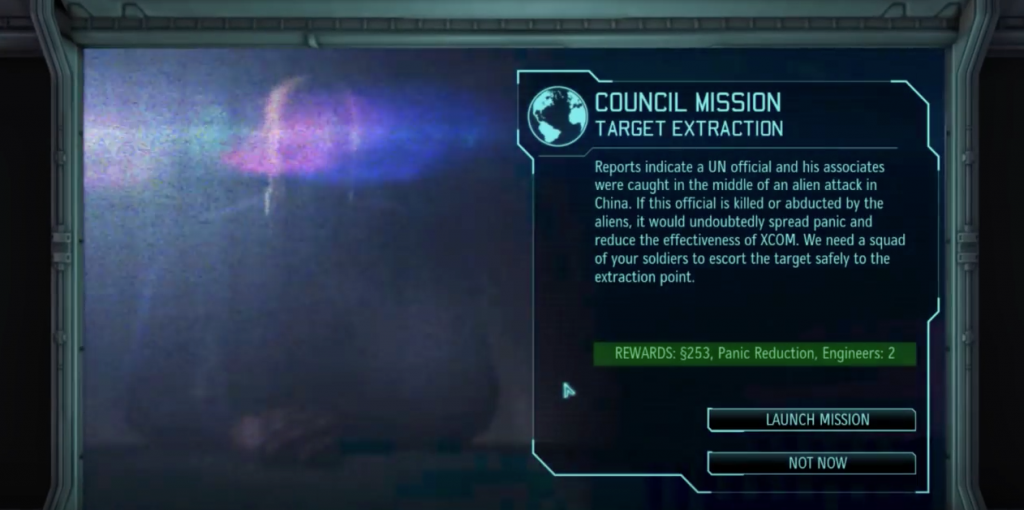

In XCOM: Enemy Unknown and its 2013 DLC expansion XCOM: Enemy Within, the Commander is responsible for the administrative and bureaucratic upkeep of the organization, the on-the-ground assault of alien facilities and defense of humans at abduction and terrorism sites, and the orbital and aerial defense of funding nations. The game divides its time progression into months, and at the end of each month, the Commander is given a report card summarizing XCOM’s successes and failures for that month. As part of this report, funding nations that have become too panicked can withdraw their support from the organization. Allowing eight nations to withdraw ends the game. Preventing this outcome through defensive maneuvers and support, while overcoming the alien onslaught through direct assault of their bases and landed ships thus form the primary objectives for players.

To meet these goals, players oversee the bureaucratic functioning of XCOM during “base management” and engage in direct combat during the “squad-based tactics” phase. Mechanically, race serves no inherent ludological, rule-based role in the design of the game. Despite being racially diverse, XCOM’s soldier base does not gain race-based statistics; all statistics are determined by equipment, classes, and military rank. Similarly, nations serve as mostly aesthetic frames for the funding, mission sites, and Council-based mechanics. But these aesthetic frames are very important to the structuring of players’ affective relationship to the game. For instance, witnessing a nation withdraw from XCOM—and it appears to visibly fall to the alien incursion thereafter—produces an affective drive in players to reduce panicked outcomes as much as possible.

The game primarily does this through three techniques: (1) producing interpersonal commitments between the Commander and XCOM’s multinational staff and soldiers; (2) illustrating the one-ness of the globe through modular representations and sites of engagement; and (3) positioning XCOM’s approach to global multiculturalism in contrast to competing ideologies. That is, the player is driven to feel connected to XCOM’s staff through their racial and national differences, but de-emphasizes those differences as actually mattering in any formal, rule-based manner. Players have to invest heavily in the training of their soldiers to ensure they can compete with increasingly difficult enemy encounters, and, in doing so, begin to develop a shared experience on missions that can build a sense of relationship between players and their soldiers. And, as each soldier represents their countries via a flag emblazoned across their upper backs, the relationship between players and soldiers microcosmically represents and emulates the Commander’s relationship to the countries of the world. Indeed, the game includes a “memorial” for deceased soldiers, reminding players of the harsh realities of war but also treating soldiers as real people with real origins and national ties. In this sense, players are simultaneously accountable to the funding nations themselves and to individuals from those nations in their employ, facilitating an affective, emotional tie to the cause that is rooted in tight social connections and shared experience on the battlefield. It’s not solely a matter of the rule-based funding mechanics that drive the player; the sense of urgency around saving entire nations of people results in a desire to save more than the bare minimum of nine nations or partial squads.

The Commander is, thusly, accountable to a multicultural XCOM just as the player is accountable to a globally interconnected Earth. This approach is then verified as proper through the lack of local specificity of mission sites and the racial and national ambiguity of escort mission NPCs. That is, Corporation warehouses can be located in Lagos, Sapporo, and Kansas City; diners can be found Sydney, Beijing, and Bloemfontein. Escort targets, such as Anna Sing and Hongou Marazuki, have names that are ambiguously global, due to the use of surnames common between languages with slight errors or variance in Romanization or Anglicization. At its core, the modularity of mission sites and NPCs yields a sense of one-ness of Earth that continues to tie players to its shared struggle against the alien invaders. In contrast, the aliens and the “human traitors” that join the pro-alien organization EXALT come to represent competing, failed racial ideologies; the aliens emphasize highly eugenic forms of racial caste ordering and hierarchy, while EXALT, whose membership is exclusively white and male, represent the Amero/Euro-centric and white supremacist problems of color-blind post-racial futurity. These three techniques—of simulated interpersonal accountability, representative verification, and external comparison—structure and produce the necessary affective response from players necessary to traverse the game-as-text appropriately.

The Board Game

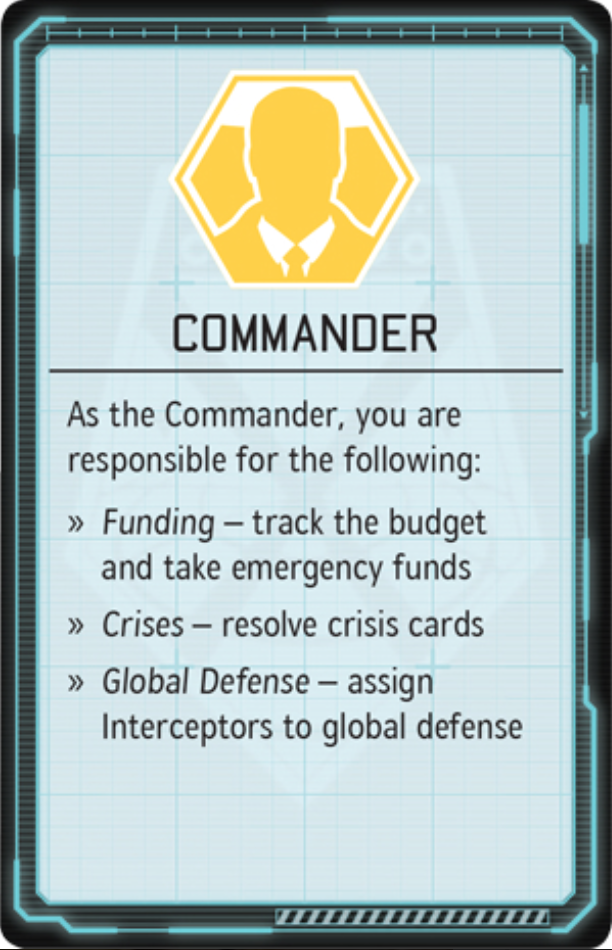

Whereas the single-player XCOM video game positions players in the role of Commander, XCOM: The Board Game is designed for up to four players, with distinct bureaucratic roles for each. The original Commander responsibilities are still central to the game play, but are now divided between the “Commander,” responsible for budgetary and aerial defense, and the “Squad Leader,” whose primary role is combating ground units and alien invaders in the XCOM base. The video game’s CO Bradford and Dr. Vahlen are replaced in the board game version by players as the “Central Officer,” who communicates responsibilities to other players and manages satellite coverage, and the “Chief Scientist,” who researches new technology for players to improve their abilities when confronting alien threats. Dr. Shen’s responsibilities are either absent or offloaded onto the Chief Scientist’s R&D work. All four roles are tasked with defending Earth against alien threats by working collaboratively to improve and build upon XCOM’s resources and capabilities. The board game is divided into two phases—a “timed phase” and a “resolution phase”—which are managed by a digital app usable on mobile devices or computer. During the timed phase, players make rushed, snap decisions under strict timed limitations about their respective bureaucratic spheres of influence—which items to research, which continents to aerially defend, etc.—oftentimes competing for resources despite sharing the ultimate goal of protecting the planet from the incoming assault. Those decisions are then “resolved” through dice rolls and player intervention during the resolution phase.

As with the video game, race and nation do not figure into the formal rule mechanics defending Earth. Unlike the video game, however, they also do not visibly figure into the aesthetic and subsequent affective structuring of the game, either. Without voiced and animated NPCs or explorable global mission sites, the emotional cueing and priming found in the video game that attempts to guide the player to a particular affective space is absent, unreplicated in textual or visual form in the board game’s format. Perhaps more importantly, however, the framework of funding nations and diverse teams are erased, as well. In lieu of nations, players defend entire continents without regard to their geopolitical states. Soldiers do not enter the game through recruitment from supporting nations, instead occupying a central recruitment pool for later purchase. Overall, the game foregoes the multinational, “shared humanism” ethos of the video game to instead focus more heavily on the bureaucratic management of the base and the probability risks of confronting alien threats.

In this regard, the board game employs a much different affective structuring to elicit player engagement. The timed phase replaces the sentimentality of the video game with an intense panic over lack of time, disrupting the players’ capacity to thoroughly strategize and communicate, despite demanding it of them. And, indeed, players will panic. The timed phase does not offer substantial time for decision making, and one of the primary differences between difficulty levels on the app is the amount of pauses afforded to players during this phase. The sense of constant threat and dire circumstances, and the necessity of rapid efficiency and proper time and resource management as a result, are the primary affective drives of play for the board game. While both the board game and the video game rely on fierce urgency to drive action, it manifests differently in its execution. The fierce urgency of bureaucratic efficiency replaces the fierce urgency of shared humanity’s salvation. And in that sense, XCOM: The Board Game doesn’t necessarily not include race, but rather adopts a racial logic in its affective structuring akin to bureaucratic management. That is, that racial difference doesn’t matter formally; technical expertise and efficiency do.

But, like in bureaucratic organizations, the formal dimensions of technical and corporate relations are but half the story. As sociologist Charles Perrow writes,

The development of bureaucracy has been in part an attempt to purge organizations of particularism. This has been difficult, because organizations are profoundly “social,” in the sense that all kinds of social characteristics affect their operation by intent.

Indeed, the emergence of the “human relations” school from the late-1920s to the 1940s, and the subsequent professionalization of “management” with a distinct focus on “good leadership” as a central role in organizations is testament to the profound importance of social relations in organizational labor. And nationality and racial difference shape and influence otherwise highly bureaucratized role relations. The same can be said of other forms of social categorization and identity. Indeed, in business and leadership scholar Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s pivotal study Men and Women of the Corporation, she illustrates “how relative numbers—social composition of groups—affect relationships between men and women (or any two kinds of people)” and how gendered behavior in organizations is not psychosocial or inherent in given job responsibilities, but a “response to the problems incumbents face in trying to live their organizational lives so as to maximize legitimacy or recognition or freedom.” In an effort to purge particularism, bureaucratic technologies merely positioned identitarian categories of persons and the social relations they influence in the latent, informal dimensions of organizational life rather than its overt, formal dimensions. Organizational rules alone do not fully encapsulate the work of and the work within bureaucratic organizations.

Affective Structure as Informal Game Studies

I wish to suggest that we take XCOM: The Board Game’s adoption of bureaucratic technologies and deracialization therein as a metaphorical launching point for engaging with the question of how to better account for nation and race in games and play. As in bureaucratic organizations, which, like games, are highly formal rule-based systems designed to facilitate and guide action, nation and race are rendered absent in formal logics while they surface continually in the informal and otherwise unaccounted-for social relations between actors. These social relations can range from direct discursive engagements to much more ephemeral affective sentiments in the workplace. Formal organizational rules only tell half the story of a given bureaucratic system, partially in the service of occluding the informal, latent organization driven by affect, emotion, and meaning between social actors.

The same, perhaps, should be acknowledged regarding race in games. Rather than focus analysis on the formal rule-based dimensions of games, we must understand those rule-based dimensions as working simultaneously alongside an affective structuring that guides players to certain sentiments, even if subjectively variable in its execution. In this regard, games can be understood as necessarily raced, as embedded in their affective structuring logics are some presumption about both the player as a human subject and about social relations more generally. XCOM: Enemy Unknown positions its relationship to race as one of shared humanism akin to multiculturalism, wherein all peoples of the world can work together in harmony and embrace difference without acknowledgement of internal conflict. XCOM: The Board Game adopts the deracialized, color-blind logics of bureaucratic control and management, seeking to erase difference in the service of efficiency. Both are highly raced logics.

To account for such racialization, and for affective structuring as a key element of game design and play, I wish to suggest we engage with games not as formal texts—as is often the case in the humanities fields—but instead as complex organizations. Erving Goffman, in his 1974 Fun in Games, described games as “situated activity systems,” that emphasize and highlight certain forms of meaning-making through their construction of “largely what shall be attended and disattended” (i.e., producing a hierarchy of meaning and relevance) and as “world-building activities” rooted in their social dimensions. And while games are about the production of explicit fictional worlds, sociologists account for the production and management of emotion and affect beyond formal rule structures in organizations, often addressing such issues as sound and music, spatial relations, and performance and affective role adoption spawning out of developments from Arlie Hochschild’s early work on feeling and emotion management. Embracing these analytic strategies and research approaches, I believe game studies will be able to better account for nation and race as visible and functioning in game spaces even in the absence of formal game mechanics around race, such as the highly eugenic logics of Dungeons and Dragons (1974) or Skyrim (2011), and in the absence of explicit, visual racial representations, as we might find in Puerto Rico (2002) or the Grand Theft Auto series (1997-2013). Nation and race operate also at the level of informal affective structuring, a scaffolding of meaning beyond the formal rules of play. Thinking about nation and race as inherent components in the informal structuring of engagement with games, we can begin to uncover and unravel the racial logics that guide affective responses from players through informal, non-rule-based structuration by identifying their playable allegories, their “allegorithms.” Acknowledging that, even in the absence of their explicit presence in formal gamic rules, we can see that “win states” are not devoid of social meaning or of symbols like nationhood and race.

—

Featured image by Joshua Livingston on Flickr, licensed under CC BY.

—

Evan W. Lauteria is a PhD student in Sociology at the University of California-Davis, where he works in the UC-Davis “ModLab,” an interdisciplinary digital humanities and video games research lab. His primary research interests include production of culture, formal organizations, video games, gender and sexuality, and comparative-historical methods. He is the co-editor of Rated M for Mature: Sex and Sexuality in Video Games (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015), and his current research is a comparative-historical analysis of Nintendo and Sega’s business practices in the 1980s and 90s.