Live streamed tabletop roleplaying games (TTRPGs) are doubly mediated experiences. Susana Tosca describes tabletop roleplay games as a “hybrid entertainment form” that is “highly intertextual and convergent.” This highlights relations to other media, but fails to emphasize how TTRPGs themselves are a medium through which multiple people engage in participatory storytelling. That is, the narrative expression of the game’s designers, the interactions between players, including the Game Master (GM) who coordinates the story for the rest of the players, and the stories that arise from these interactions, are mediated by the game’s rules. Live streaming remediates TTRPG gameplay through digital networks, bringing the experience to audiences distributed across the world and tuning in at a different times. As TL Taylor argues, “Live streaming programs, while riffing on the televisual, have developed their own unique set of conventions, practices, and pleasures. They have their own sets of celebrities, their own histories and forms of interaction with their audiences.” This requires media scholars concerned with games and play to attend to both forms of mediation.

In a March 24, 2020 live-stream of Far Verona, a cyberpunk-themed roleplaying game using the Stars Without Number system streamed on the RollPlay channel on YouTube, the character Johnny Collins (played by “EE”), a synthetic humanoid, seeks help from a mechanic named Rocket (played by GM Adam Koebel). Rocket takes Johnny to a back room away from the rest of the characters and hits on him before plugging a device into Johnny that gives him a “robot orgasm.” Koebel narrates the experience, complete with blurred vision and buckled knees, before saying through his laughter, “I think, maybe, that’s the last shot, the shot of the episode.” This unwanted sexual encounter, a sexual assault, would be the final scene of not only the episode but the entire game. A temporary break that would become a permanent cancellation was announced by Koebel in a video hosted by itmeJP, the founder of the RollPlay channel, on March 31, 2020.

In this article, we focus on this interaction as an exemplar of the problem of player safety in live streamed TTRPG gameplay. The next section reviews theorizations of play developed by games scholars and the notion of bleed emerging from the Nordic LARP community. These are critical for our premise, which is that not only does TTRPG play take place in and across multiple frames, but the frames themselves are acted upon. We will show a layered exchange of actual play in which players move across and blend multiple frames as they work to achieve player/GM and character aims, some of which are in conflict, and which are further complicated by the public character of this interaction. We conclude by asking whether the current set of safety tools for TTRPGs are sufficient, and consider the role of the audience as an additional pressure that shapes actual play when it is a monetized streaming event.

Boundaries, Bleed, and Play

While community, sociality, and relationality are critical touchstones in recent TTRPG scholarship, little attention has been given to responsibility within TTRPG play groups. In Functions of RPGS, Sarah Lynne Bowman argues that TTRPGs are “community building” activity. Bowman describes the interactional dynamics of role-playing in terms of functions such as altering perceptions, overcoming social stigma, and shared ritual, arguing that this “shared experience creates a bond out-of-character,” and when she does address in-group social dynamics it is in the context of problem-solving in-game; only gesturing to in-party conflicts. Bowman also offers a typology of social conflicts between players, which includes schisms, internet communication, intimate relationships, creative agenda differences, GM/player power differentials, and bleed. The exchange around which we organize this article could fit into several (possibly even most) conflict types in Bowman’s schema, depending on one’s gloss of player intent and responsibility, and where one draws the temporal boundary around the ‘conflict’ as an event. We focus on how specific player interactions can come to produce real world outcomes and experiences, whether they be deepened bonds or lasting conflicts. Our analysis of the Far Verona exchange allows us to specify and deepen the concept of bleed, a phenomenon of blended frames.

Beyond recognizing that bleed is an important component of this interaction, we aim to use the interaction to describe how bleed can happen, and locate it within a set of accountable TTPRG practices, or ethnomethods. Ethnomethodology, coined by Harold Garfinkel, is an empirical orientation to the locally produced orders of meaning and interaction, which Garfinkel called “ethnomethods.” Thus, rather than being a particular theory, discipline, or analytic tool, ethnomethodological studies attend to situated, moment-by-moment interactions, include the words spoken and other non-verbal action such as pauses, overlap, tone, volume, and tempo changes. Depending on what is relevant to the activity in question and how it was documented, the analysis may also attend to gestures, gaze, and interaction with objects and materials in the environment, as we do in this study.

The concept of “bleed,” coined by Emily Care Boss, originally emerged from the community of players and developers of Nordic larp. In the early 2000s, when the academic study of games fixated on the idea that games stand apart from reality, Nordic larpers developed the emic term bleed to mark off instances where the competing realities of everyday life and gameplay influenced one another. In this section, we first discuss the magic circle in order to contextualize how recognizing bleed re-embeds games in reality rather than emphasizing their separateness. We then discuss the notion of bleed and its relation to what scholars describe as dark play, deep play, and brink play, in order to give a better sense of how bleed occurs and how related features of play have been theorized. We close this section by turning to the limits of safety tools that have been designed precisely to protect players from the risks entailed by bleed.

The notion of the magic circle, extrapolated from Johan Huizinga’s claim that play takes place “outside and above the necessities and seriousness of everyday life” is a contested concept in the study of games and playful media. Formalist games scholars leveraged the term, particularly Huizinga’s argument that all play occurs in the spaces “temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart,” to make a case for the distinct structure of games and gameplay. As game studies has moved away from efforts to define and describe the object of study and towards approaches that consider the social, psychological, and cultural dimensions of games and play, the concept of the magic circle has been productively critiqued.

Critiques of the magic circle are explicitly and strongly articulated by both Consalvo and Calleja. Consalvo’s polemic “There is no Magic Circle“ leverages her work on players’ conceptualizations of cheating to argue that, for players, there is no demarcation between play and everyday life. Players bend and break game rules to accommodate their busy lives, win grudges against other players, and repurpose games for ends aside from simple pleasure. Consalvo writes: “[The magical circle] emphasizes form at the cost of function, without attention to the context of actual gameplay.” Like Consalvo, Calleja points to the work of cultural anthropologists Thomas Malaby and TL Taylor to show that distinction between the ‘ordinary world’ and the ‘temporary world’ cannot be marked in actual gameplay or the “situated study of players.” This means that the concept of the magic circle is a limited, even ineffectual tool for studying play. Calleja suggests that this is a problem endemic to the concept as Huizinga sought to simultaneously and paradoxically construct play as an ideal space circumscribed from everyday life and claim that play pervades culture.

Both Consalvo and Calleja highlight Goffman’s frame analysis as a more productive critical tool for interpreting complex social situations. A sociologist studying symbolic interaction, Goffman employed frames and keys to analyze social interaction. Frames describe ways of understanding/defining a situation that delimit sensible responses (e.g. “Sir, this is a Wendys”), while keys signal that an already defined situation should be perceived differently (e.g. “but now it’s a meme”/Tik Tok). Consalvo, in particular, draws from Fine’s work with TTRPG player communities, highlighting Fine’s reconceptualization of keys as signals for shifting to different frames, rather than alternative versions of an already existing frame. Fine’s analysis, in turn, points to three common frames for TTRPGs corresponding to the person, the player, and the character, respectively: ‘‘the world of commonsense knowledge grounded in one’s primary framework, the world of game rules grounded in the game structure, and the knowledge of the fantasy world.” The context of live-streamed gameplay adds a fourth frame to the consideration, that of a performer in a mediated entertainment production.

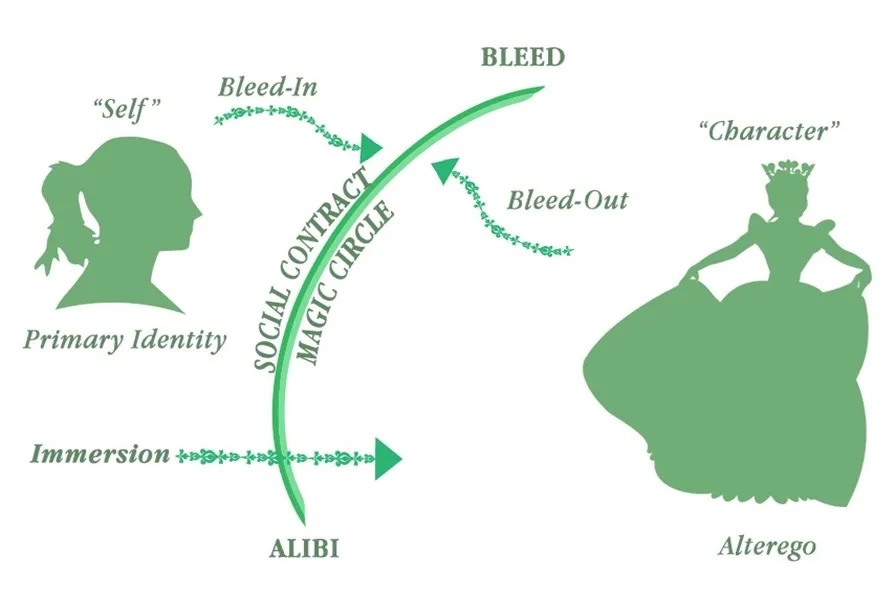

The notion of bleed becomes intelligible when approached in this way, but unlike Goffman’s frames, bleed rests not upon the shifting or the distinction between various frames, but on their ambiguity, leakage, or overlap. Bleed experience stands in contradiction to Goffman’s position that “for every utterance or action only one frame is active.” With Jørgensen, we maintain that the TTRPG gameplay in question here “is not on the threshold between different states, but absorbs features from both side[s] of the threshold.” Indeed, bleed describes situations where multiple frames not only intersect but spill over into one another. Piironen and Thurøe explain:

Bleed is experienced by a player when her thoughts and feelings are influenced by those of her character, or vice versa. The experience of bleed often comes when players are playing close to home or on themes that are part of the player’s everyday life, like friendship, love, or death. Bleed can make the game seem more powerful and meaningful, and therefore it’s an active goal for some players.

Montola differentiates between “bleed in [which] occurs when a players’ ordinary lives [sic] influence the game, while bleed out occurs when the game influences players despite the protective framing.” Significantly, Montola understands bleed as a phenomena that not only pierces the frame of the game, but straddles multiple frames; it “is based on a double consciousness: players both acknowledge and deny the nature of play.” We build on these insights from Montola, in particular the dual directionality of bleed and the conception of bleed not only as an effect of play but also as a type or style of play.

In much of the literature on the subject, bleed is an evocative name for the effect of blurred boundaries and leaky frames and signals both risk and reward. Seekers and theorists of bleed experiences tend to glorify bleed and related forms of play for their ability to provide profound “positive negative” experiences, to free players from social prohibitions, or to expand expressive capacities of games and play. Building from Montola and others, Poremba coins the term “brink play” to describe gameplay that puts game rules in implicit conflict with social rules,“ which she argues, “allows play with social rules at a reduced risk, removing much of the prohibition behind breaking the taboo —it is after all, ‘just a game.’” This is similar to how Schechner conceives of “dark play,” to the extent that it “involves intentional confusion or concealment of the frame” and has the effect of creatively destabilizing normative modes of being and thinking. Critically, for Poremba, Schechner, and others, bleed draws attention to the borders between everyday reality and the fiction of the game to invite the possibility of deconstructing and reimaging social realities.

Without discounting these rewarding possibilities, our analysis ruminates on the risk, which has been under-theorized and grievously under examined. In her effort to locate the seriousness of all play, Jørgensen discusses bleed in relation to deep play. Drawing from Clifford Geertz, for Jørgensen deep play is play “where the risks to the player are so high that it is irrational to engage in the play act at all.” In line with highlighting the risks inherent in all play, metaphors of bleed, leakage and seepage also evoke a lack of agency. Sometimes, ideas or actions flow across boundaries in intrusive ways. Not only are these occurrences uninvited, they can be disempowering and even traumatic. In such cases “the alibi of the felt experience being ‘just a game’ and ‘not real’ is compromised” in ways that precipitate emotional, psychological, or even physical harm to players.

Indeed, the TTRPG community has developed safety tools and protocols that aim to safeguard players from emotional harm and trauma while improvising in a fictional world in which players may witness, enact, or be subject to danger, violence, intimacy, and dehumanization. Among the most prominent of these tools are the X card, developed by John Stavropoulos in 2013, and lines and veils, developed by Ron Edwards in 2001, both of which are designed to communicate boundaries between players. Where the X card is tool used in-game by a player to signal their discomfort to the GM and prompt a change in topics or themes lines and veils are a pre-game tool enabling players to indicate what topics and imagery they are comfortable dealing with directly, what topics and imagery they only want to deal with implicitly (e.g. veils), and what topics and imagery are completely out of bounds (e.g. lines).

While we see them as a positive step, this case study shows that conventional safety tools like the X card and lines and veils are insufficient on two related fronts: 1. Safety tools are premised on an understanding of bleed which acknowledges risk while obscuring agency. As a result, 2. They are over-reliant on explicit refusals, even when most refusals in ordinary interaction are indirect. As in the case of indirect sexual refusals documented by Kitzinger and Frith, we find that indirect to increasingly-direct refusals in our instance of play are recognized and responded to sensically, but selectively ignored. Thus, recognizing bleed as a feature or a core force in play, as something that is both integral to the activity and as something that happens within players, makes accountability between players harder to keep in view but also makes doing so imperative.

We want to bring player agency to the forefront and show that by looking closely at the turn by turn interaction of play, the boundary between play and life is actively and dynamically negotiated, manipulated, and utilized. In other words, overlapping frames are not simply a situation in which players find themselves facing fluid, inherent risks, but are acted upon in organized ways that can be described and analyzed. By specifying bleed as play practice, as a technics of TTRPG play, we can begin to illuminate the accountable methods by which active manipulation of frames can cause harm. On the other hand, active manipulation of frames can also resist and highlight potentially harmful interactions. We draw attention to these methods with an eye toward building more grounded safety tools that go beyond contending with inherent narrative and situational risks, and emphasize agency and accountability in game play.

While most TTRPG play occurs either in-character or out-of-character, we highlight instances where the frame is ambiguous or even multiple, in which the “I” is either the character or player, or both. We further complicate this by also considering the primary frame of social reality and a fourth frame that is both independent of and encompasses the others, that of the live-streamed commercial entertainment performance. In what follows, we aim to uncover and elaborate the ethnomethods of bleed play. Put otherwise, our concern is with re-specifying the moves or plays that might otherwise get described as bleed, but which are a more active manipulation of intersubjectively agreed upon frames. This repertoire of bleed play techniques includes epistemic maneuvers, linguistic shuffling, and embodied performances that cut across and blend these frames.

Ethnomethods of Bleed Play in Far Verona

Far Verona, a live-streamed actual-play of the Stars without Numbers TTRPG hosted on the RollPlay YouTube channel from May 2018 to March 2020, was created, written, and game-mastered by Adam Koebel. Koebel is a celebrated game designer (Dungeon World) and a celebrity in the TTRPG community. In addition to his prominent role GMing multiple games on the RollPlay channel, he had been invited to speak at prominent gaming conferences, appear on numerous streams and shows, write for multiple games, and was the GM-in-Residence for Roll20, the largest virtual table-top website. As such, Koebel’s power in the Far Verona game extended beyond the explicit authorities legitimated by his role as GM. We begin with the players’ and Koebel’s comments on and accounts of the incident in the weeks that followed. However, our analysis focuses on the communicative gameplay interactions at the table itself.

Koebel offers a cursory apology to the players and fans of the show in both a March 31RollPlay video with itmeJP and his blog. In the video, Koebel’s primary focus is on safety tools:

The big thing here, I think, for me is to recognize that these situations can be avoided by implementing the right protocols. For me the biggest take away is that… I wanted to apologize for missing that integral step. Normally it’s something we do at the beginning of a campaign. We talk about themes. We talk about lines and veils. We talk about safety protocols. But… we didn’t for Far Verona and that’s something I regret, I regret missing that point. It’s something we usually do, and it just didn’t happen and this is the result (emphasis added).

In his blog post three months later, he also casts blame on the live-streamed nature of the game, stating “The nature of most content on Twitch is that it’s unrehearsed and spontaneous. In roleplaying, players work together to create an improvised narrative and I was doing so in a highly public venue.”

EE describes the encounter as something that “felt premeditated,” having occurred despite recently telling Koebel that she wanted her character, Johnny, “to be able to say NO to more people.“ She also notes “multiple red flags,” including Johnny backing away to refuse an initial advance and Johnny telling Rocket that he wasn’t “thirsty,” a slang term referring to sexual interest. EE also comments on the way that it happened in front of the streaming audience of thousands, and emphasizes that Koebel abruptly ended play after the assault, leaving no in-game opportunity for players to respond to, process, or resist what had happened.

The contrast between these accounts illustrates the shortcomings of relying on explicit refusals for preventing sexual assault. Koebel distributes accountability to the “we”, the group that failed to implement a safety tool, but even if a protocol had been in place, the burden would have fallen to EE to be explicit rather than indirect. Recalling Kitzinger and Frith, relying on formalized rules or specific “magic words” to ensure safety or assure consent ignores the varied ways, direct and indirect, that people conversationally engage in (and usually recognize) refusals. Kitzinger and Frith describe how college-aged men were seemingly unable to heed indirect refusals in a sexual context, while clearly able to recognize such refusals in other contexts. They argue that “Just say no” as a sexual assault prevention policy places the burden of responsibility on the person at risk of assault, and artificially lowers expectations of young men’s capacity to understand ordinary refusals in sexual contexts.

In the sequence of actual play during this episode of Far Verona, Johnny Collins/EE makes several implicit refusals that are not taken up by the GM, Adam Koebel. First Johnny goes along with the processes needed for the repair, but responds to Rocket’s questions in a markedly different tone than the way they are delivered. Next, EE narrates Johnny physically backing away from Rocket. Finally, EE – out of character – speaks up about Johnny’s programming, specifically, Johnny’s lack of capacity to experience, recognize, or respond to romantic/sexual attraction. This is preceded by Koebel’s character, Rocket, convincing Johnny to accompany him, alone to a back room where he ultimately sexually assaults Johnny. We highlight these moments because they emerge from various frames: that of the characters, the players, and the performers. Importantly, in overflowing and fluidly moving through these frames, the response to these refusals illustrates how players enact, ignore, and reject the boundaries of TTRPG gameplay.

Our transcripts adopt some of the conversation analytic conventions developed by Gail Jefferson, to indicate utterance onset, overlap, pauses, and to describe gestures and expressions. The lines in each excerpt are numbered according to a full transcript that can be found in Appendix 2. We distinguish between character speech (Rocket, Johnny, Haley, Autumn, Jasnah) and player/GM speech (Adam Koebel (AK), EE, Vana (V), Mark Hulmes (MH), and Marcus Graham (MG)). Often player and character will share a line number, for instance, when the performer narrates before speaking. We indicate EE’s use of a voice modulator for her in-character utterances as Johnny by italicizing Johnny’s name when the modulator is used. Finally, there are lines where both names are referenced because it is notably ambiguous whether the words or actions belong to the player or the character. In transcribing in this way, we aim to respecify ‘bleed’ by capturing how the functions and consequences of manipulation of frames are enacted through the mundane yet specific micro-practices, mechanics, performances, and negotiations local to TTRPGs. (See Appendix 1 for a glossary of transcription conventions used).

Splitting the Party, Drawing Blood

After a particularly harrowing combat in an industrial facility in the previous episode, the March 24 session begins with the characters further injured as they escape an explosion. They find shelter in a mechanic’s shop run by Rocket, who Koebel describes as a “rockabilly Bruce Campbell”. While most of the players are healed by one another, as an older model robot, Johnny requires help from Rocket, who offers to take him to a back room so that he does not have to remove his chassis in front of the rest of the group. What unfolds is an interaction in which Koebel, having perhaps let slip more of his/Rocket’s intentions than he would like the characters to be able to act on, uses a game mechanic to withhold information from the characters which informs (and limits) their subsequent actions.

Vana stops Rocket and Johnny in-character (as Haley) and expresses concern about Johnny going off alone, reminding him of a recent betrayal by another NPC. EE turns on the voice modulator on her microphone to respond in Johnny’s voice and invites Haley along but then reconsiders when Koebel narrates: “Johnny, Rocket makes a face when he realizes Haley is going to come with [you].” He begins to describe it before saying, “Actually, you know what, can you make a roll? I wanna see how much you can read his internal business here” (line 21). In this instance we can observe two ethnomethods of bleed in TTRPG play: one epistemic, and one grammatical.

The first is an ethnomethod of bleed which is epistemic – it manages the boundaries between character and player knowledge. Koebe paused the narration and imposed a die roll to determine how much subtext the characters pick up on, specifically whether Johnny picks up on Rocket “mak[ing] a face” when he hears that Haley intends to join. As Koebel’s initial response demonstrated (“Actually, you know what, can you make a roll?”) the die roll was not required but rather a technique imposed to withhold information, enable intrigue and uncertainty, and build dramatic tension. This move hedges against the possibility of epistemic bleed in by utilizing the game mechanic to predispose EE to have Johnny decline Vana’s company and leave alone with Rocket. Working from Koebel’s ruling based on the die roll – that Johnny doesn’t pick up Rocket’s “internal business” – EE proceeds to have Johnny reassure Haley that Johnny knows this guy from previously using his services, and they can trust him. It’s notable that this past experience is imagined as a backstory, rather than having been played through earlier. The decision to have Johnny decline Haley’s company relies, then, on a tacit agreement between players that Johnny really does have a reason to trust Rocket. Trust between players is leveraged to establish support for trust between characters.

Koebel also employs a second TTRPG ethnomethod, this one grammatical, which heightens tension for the players. He begins by speaking to Johnny in third person (“he, Johnny”) but concludes using second person tense to ask EE for a die roll (“you”). This technique of addressing the player as the character is a commonplace in many GMs’ repertoires intended to enhance player-character identification and enable bleed. But Koebel takes this one step further by conflating the two in one single utterance. That is, by evoking both the in-character and out-of-character frames in the same statement, Koebel is able to “simultaneously maintain a sense of alibi, and to weaken the protective frame” of the game. This form of address is far from uncommon as Koebel has previously and will continue to address players in second-person. And where it seems fairly mundane for the GM to tell players what happens when “you” press a button or that “you” are able to open the door, this mode of address takes on a different tenor describing an unwanted sexual encounter at the end of the session.

Despite Johnny and EE’s repeated refusals, Koebel describes Rocket placing a device against a port on the back of Johnny’s neck and stimulating a “robot orgasm.” His narration is entirely in second person and seems to be cognizant of Johnny’s lack of agency, at one point describing Rocket approaching Johnny with his hands up “like you’re a scared animal” (line 116) EE, meanwhile, maintains the distinctions between player and character, turning on her voice modulator to say, “okay, sure,” when Rocket indicates he is going to start the repair procedure before speaking in her own voice as a player to narrate, “Johnny has no idea what he’s [Rocket] going to do. No idea” (line 120). Koebel proceeds to describe Rocket stimulating Johnny with the device, and continues to grammatically conflate the third person and second person. Employing this common grammatical GM ethnomethod as a technique of bleed play, Koebel facilitates bleed out at the table. By more closely suturing player and character, and thereby better enabling identification and immersion, both EE and Koebel are primed to carry the affect from the gaming table out into their lives.

Implicit Refusals: Suturing Bleed

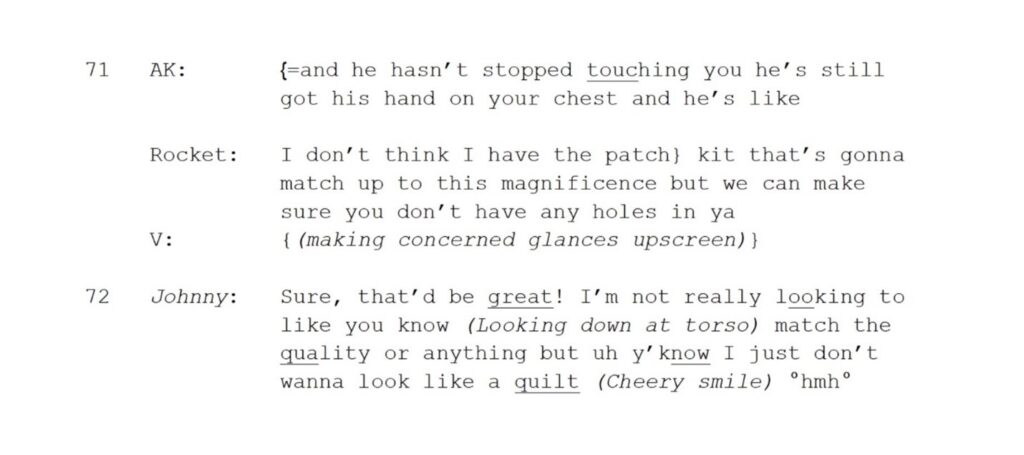

Before the assault, but after the discussion among the players about his safety, Johnny allows Rocket to take him to his separate workshop space. Rocket asks him to take his shirt off, stands “real close” to Johnny, touches his torso, and admires the workmanship of Johnny’s skin:

In this excerpt, Johnny brushes off the awkwardness of Rocket’s overly long, intimate gesture and compliment by tonally sidestepping it. Responding brightly, “Sure, that’d be great!” (line 72) and joking about not wanting to look like a quilt, Johnny’s utterance combines a palliative and a weak acceptance. Johnny accepts the repair procedure while deflecting the awkward compliment. While Rocket’s actions are largely narrated by Koebel as GM, EE’s responses as Johnny entail physical gesture and action that respond to actions narrated by Koebel; looking down at her chest as Rocket’s hand lingers on Johnny’s torso and joking about looking like a quilt. These gestural refusals demonstrate a third ethnomethod of bleed play: that of embodied performance.

In this moment of dialogue, EE embodies Johnny’s response, and the frames that separate EE and Johnny blur. Because Haley is, diegetically, in another room while this is occuring, Vana’s concerned glances can only be read as the out-of-character expressions of a fellow player.

While this scene involves shifting between the in-character and out-of-character frames, those frames are, for the most part, distinct. But the brief moment of overlap between frames, sutured together by EE’s embodied performance, creates a channel for bleed play. And coming from EE, it also suggests a shortcoming of the terms dark play and brink play, which describe activity intended to subvert normative social conventions or engage in something typically forbidden. EE’s embodied conflation of frames is, in fact, part of an effort to deflect Koebel’s transgressive actions and prevent the negative experience.

As the scene continues, Johnny/EE gives escalating indirect refusals. Shortly after the previous scene, Rocket compliments Johnny’s chassis and describes him as beautiful, touching Johnny’s face with the back of his fingers.

![92 Johnny: (Eastman miming Rocket’s hand on her cheek with one hand and patting it 6-7 times with her other hand, as Johnny)Thanks buddy! [I really appreciate it that really makes me feel great. Um (.) Can you e like (1.0)(looks down at their torso as if to indicate he wants Rocket to do the repair).] V,MH: [(visibly laughing and MH nodding, though muted on the stream)] 17 93 EE/Johnny:I’m just gonna like take a step back here, just step (pushes chair back away from the computer and then pulls back up)](https://analoggamestudies.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Lines-92-and-93-1024x525.jpg)

Vana and Mark Hulmes’ laughter following Johnny’s hand pat acknowledges Johnny’s refusal. It is clear to the players that Johnny wants nothing beyond the repairs Rocket has offered. Nonetheless, the other players’ affirmations cannot “bleed in” to the moment of game play itself, since none of their characters are present to witness the escalating refusals.

After Johnny steps away, Koebel has Rocket awkwardly blather, knocking his tool, muttering to himself “ Ah stupid Rocket come on….” and telling EE “You can see him trembling” (lines 94-97). Koebel plays his character’s response in a way that shows that he recognizes Johnny’s stepping away as a refusal, but turns the focus on his own character’s struggle with perceived rejection. Koebel/Rocket’s response is transparently read as a manipulation tactic by Vana, who dramatically rolls her eyes and shakes her head. What, then, do we make of Koebel’s post-hoc evasion of accountability with which this article began? Regardless of Koebel’s conscious intent, by examining the interaction it becomes clear he is perceiving and responding to refusals, yet ignoring them. Like the college-aged men in Kitzinger and Frith’s study, who are capable of recognizing indirect refusals in ordinary, nonsexual contexts, Koebel, too, can be held to a higher standard when it comes to recognizing players’ communicative intent.

As EE continues her efforts to rebuff Rocket’s advances toward Johnny, the shift between in-character and out-of-character frames is, once again, ambiguous. While the refusal is increasingly explicit, the matter of who is refusing – the player, or character, or both – is uncertain. Again, EE blurs and overlaps the frames not to transgress norms through dark or brink play, but to maintain them in order to protect herself. This suggests that bleed play, the overlapping of frames, can, when examined closely, be a method of resisting and refusing the bleed effect.

Indeed, there is a clarity to EE’s performance that may be germane to a skilled player/performer in the context of remote TTRPG play, where the players are each joining from their own devices. For instance, EE’s active verbal highlighting of her character’s embodied actions may also have the function of magnification or visual description, as if to say “in case you missed it, I am doing this.” Similarly, EE mimes the hand of Rocket caressing Johnny’s cheek, bringing the caress and Johnny’s reaction to it into her own frame in spite of the player/performers being physically in different locations. EE physically enacts Rocket’s caress in order to dismiss it with Johnny’s awkward pats (using EE’s other hand). EE’s complex performance stands in stark contrast to Koebel’s subsequent characterization of Johnny as “a scared animal.” (line 115) Instead of performing “scared animal,” EE performs “asexual robot,” to what appears to be comedic effect for the other players. In spite of the virtuosity of this performance, and the clarity of her multiple refusals and gestures depicting her character’s discomfort – not only to the other the players, but presumably to much of the livestreamed audience writ large, EE’s performance to this point does not deter Koebel/Rocket.

It is at this point that EE interrupts Koebel’s narration to clarify what Johnny can and can’t recognize in this situation – and thus, what he can and can’t consent to. This is the most explicit sequence of refusals in the entire interaction, but still not enough to ward off Rocket’s advances. Immediately following AK’s narration of Rocket disparaging himself, EE breaks character to say that, while he has probably been the subject of other’s affections, Johnny doesn’t have the ability to reciprocate Rocket’s amorous intent. Koebel cuts her off with a joke about Johnny, a bartender, having been hit on by drunk housewives but EE continues to say, through crosstalk, that “I don’t think he’s ever been programmed to respond [MH interjects: “to recognize”] romantically … to recognize attraction” (lines 98-102). Here EE makes it clear that Johnny is incapable of consenting to intimacy, which Koebel seems to affirm by riffing on her comment with a joke. Insofar as it is a negotiation of the boundary of player and character, this is a kind of bleed play as well, as well as an interruption to the flow of role play action, and arguably EE’s most explicit refusal. EE’s contextualization of her character’s asexuality is another moment where the player character boundary is at once split and sutured in order to resist harm. And yet, in marking this split and clarifying the character’s orientation, we could also read this as a last ditch effort to engineer bleed out, where the player deploys their avatar’s characteristics to prevent something harmful from happening in the outermost layer of the interaction – the fictional assault that would cancel a series and end a friendship.

It doesn’t work. Koebel goes on to question how EE is playing her own character, blurring frames as he says, “But, as a counterpoint you were also not programmed to drive a car, Johnny. Today is a day of exciting new feelings” (line 105). Notably, where EE was speaking in third-person about her character, in this moment Koebel, speaking out-of-character and as the GM employs a grammatical ethnomethod again, returning his counterpoint directly to “you (…), Johnny.” EE replies with her own palliative, “that’s so true,” then circles back to describing Johnny’s palliative actions and words in response to Rocket’s reaction to rejection. EE enacts a variation of this grammatical move by switching from third-person narration (“he”) to first-person (“I”) to say “hey”, as Johnny:

![106 EE: [that’s so true (.) so ] I think that he is (.) he can see that this person wanted to display like affection or have like a tender moment, so he goes over to him and he kinda like puts his hand on his back, and um [ºheyº] 107 AK: [You feel] him like freeze up a little like oh god= 108 Johnny: Hey (gently) uh listen. I uh (1.5)(slowly opens hands) am open (.)to new adventures. So (.) (slowly) I don’t want you to feel weeeird about anything but I (.) think it’s kind of like when you have a glass of water and you’re not really thirsty you just kind of drink it you know what I mean. Does that make sense?](https://analoggamestudies.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Lines-106-to-108-1024x624.jpg)

In this sophisticated performance spanning multiple frames, EE employs a final ethnomethod of bleed play that operates metatextually. Johnny tells Rocket that he is “not thirsty,” evoking a slang term for sexual interest that Koebel is aware of, as evidenced by his use of the term during out-of-character talk with the players earlier in the episode. This language, that could exist in the world of Far Verona but certainly exists in the primary frame of the social world, is the figure at the heart of Johnny’s reply to Rocket, once again overlapping frames. But in spite of having just demonstrated through his character’s fumbling response that he recognized an indirect refusal, Koebel only takes up Johnny’s weak acceptance (I am open to new adventures) and maybe his palliative (I don’t want you to feel weird about anything), before having Rocket say “Don’t be scared” and plugging in the device that gives Johnny a robot orgasm (lines 111-120).

Conclusion/Discussion: Someone Loses an I

Why didn’t EE stop the game to issue an explicit refusal? In addition to the fact that explicit refusals are relatively rare in ordinary conversation in comparison to indirect refusals, we suggest there are two factors at play here.

The first reason is the live-streamed nature of the Far Verona game. The audience is an invisible elephant in the room, influencing play. Hope suggests that players performing for an audience tend to maximize narrative content and minimize out-of-character talk. Furthermore, Franklin argues that the social-contract between audience and player in live TTRPG actual play is the consummation of narrative. Thus the audience increases the pressure to stay in character; this necessitates Johnny’s use of bleed ethnomethods to enact palliatives, deflections, tonal changes, and eventually resort to an out-of-character but in-universe explanation of Johnny’s asexuality.

The second reason is because, as observed in Koebel and EE’s TTRPG ethnomethods – culturally situated and intersubjectively agreed upon cues and techniques for managing meaning between multiple frames – they both engage in bleed play where only EE risks ‘losing her I’. This is because Koebel’s authority as GM allows him greater agency to not only set the context and stakes of the interaction but also to manipulate the competing frames. The space between Koebel and his character, Rocket, was never at immediate risk in this interaction (though it would collapse in the weeks and months following this incident alongside his persona as a sensitive and progressive player/GM). Rather, it is EE who is simultaneously positioned and positions her corporeal and in-fiction selves within multiple frames, a gambit that exposes both to injury in an effort to stave-off a greater harm. While some of this is thrust upon her by Koebel’s storytelling, EE’s bleed play is itself creative and skillful, responsive to Koebel’s doing of the storytelling, returning his (mainly epistemic and grammatical) moves with grammatical, embodied and metatextual moves of her own. But (if ever there was a lesson bleeding in- and out- of games, this could be it) skill cannot always defeat structural power.

This analysis identifies four distinct ethnomethods of bleed play. The first, and most clearly tied to the game mechanics of TTRPGs, are epistemic moves. These bundles of routines and norms of play, governing what characters know about the game world and its inhabitants, variously restrict and enable the players actions. In this case, Koebel’s use of the perception check sidelines Vana and EE’s concerns about Rocket, and suggests that the appropriate attitude for Johnny to have is trust. A second ethnomethod identified is grammatical, and it takes two forms in this interaction. When enacted by the GM it involves the slippage between third-person and second person address, and when enacted by other players it involves the slippage between third-person and first-person address. A third bleed play ethnomethod is gestural and/or embodied performance that blurs the interaction’s frames. EE gestures toward their own body as Johnny’s body and pushes themself away from their computer to physically remove both the character and player from a harmful situation. Finally, EE weaves contemporary slang, used in a prior out-of-character conversation, into their character’s speech in a metatextual move. This ethnomethod crosses the primary frame of the players’ social reality, with the secondary frames of the players at the table and the characters in the world of Far Verona.

Just prior to Rocket separating Johnny from his party, players negotiated a code word for how Haley could know if Johnny was in danger. They laughingly exchanged comments about what mechanical sounds to listen for, then agreed upon the simple “code word” “help”. When the players reference “help” after the game session has concluded, it functions as an ironic metacommentary about how the scene went. That is, “help” existed only in the world of the characters. While the characters had planned an ad-hoc, in-world safety tool, when a player actually needed one, it was rendered unintelligible, lost in the gap between character and player.

That “help” – an improvised safe word – failed to bridge this gap emblematizes why a conventional safety tool would likely have been rendered just as unusable. We asserted earlier that 1. safety tools are premised on an understanding of bleed which acknowledges risk while obscuring agency and, as a result, 2. conventional safety tools are over-reliant on explicit refusals even though most refusals in ordinary interaction are indirect. TTRPG ethnomethods are a blend of ordinary and extraordinary interaction across frames, but we show that these aren’t blended evenly, randomly, or without agency or responsibility. Our analysis also shows that role play relies on ordinary conversational resources, negotiations, and norms, even while taking place in a fictional world and across blended player and character histories. Explicit refusals can therefore be expected to be as rare in role-played character interaction as they are in ordinary interaction. Explicit refusals that also break character and interrupt the narrative, like deploying the X card, are likely even rarer, especially with the added pressure of a live-stream audience.

The GM has orchestrated a scene in which the character – an asexual robot – does not understand or foresee what is happening to him even as the players are increasingly uneasy. This is a splitting of character and player that Koebel enforces as GM, and which only deepens as the interaction proceeds.

In this scene the subject of the assault is split: Johnny and EE. And yet, the assault is experienced, through this particular implementation of bleed ethnomethods, by both character and player. This differentiation – at the heart of bleed play – can be deployed and experienced as both a splitting and as a suturing. It is a structure over which GM and players have differential power. This differentiation is reinforced further by the presence of the livestreaming audience, adding pressure to stay ‘in character.’ As demonstrated in the excerpts above, EE’s range of responses, limited by Koebel and facing the livestream audience, become increasingly acrobatic in having her character attempt to evade the NPC’s uncomfortable advances. While Koebel splits and sutures the characters’ and players’ epistemic and affective capabilities, EE’s complex performance uses bleed play to perform protective assertions of self within the GM-imposed constraints. Elaborating her character’s lack of capacity to consent, highlighting a literal step away, and importing metatextual slang about “thirst” can be read as deployments of bleed play that suture character back to player (as if to say “I am here too”), which might have averted a harmful bleed effect, and stemmed the bleeding-out that would ultimately lead to cancellation of the series and the end of the friendship.

In this article, we elaborate the concept of “bleed” by identifying a set of TTPRG bleed play practices, play with and between and across frames, that can facilitate vulnerability. This vulnerability is only deepened in monetized, livestreamed contexts where players experience additional pressure to stay in character. And we have seen that, ultimately, even explicit safety tools like the X card or in this case, the cry of “help,” can be rendered ineffective or unintelligible, even with players who consider each other friends. Something more is required: tools that are sensitive to the ethnomethods of TTRPG play, and which cultivate higher standards of care, communication, and accountability for all players.

Having specified ethnomethods of TTRPG bleed play and the risks and consequences thereof, our research suggests that further uptake of one-size fits all tools and protocols is not sufficient to ensure player safety. It is a challenge to imagine a world in which norms of care and accountability through communication could supercede the wants and desires of the audience to a monetized livestream. And yet, TTRPG performances with a broad, popular audience are an opportunity to model flexible tools and approaches for accountable, responsive and caring play, over and against the pressure to “consummate the narrative” – the parallel of hedonistic consummation across frames is not lost on us. There is a near-certain risk that a subset of audience members would oppose any protocol that interrupts their enjoyment of the narrative, especially if it is perceived to be associated in any way with feminism and/or the promotion of social justice. Likewise, there is a near-certain risk that a subset of players who as GMs will continue to abuse their structural power at the expense of their players’ safety while laying blame elsewhere, placing the burden of intelligibility on their victim while at the same time orchestrating the terms of intelligibility. Nonetheless, there was a vocal subset of audience respondents to this Far Verona episode who would likely welcome TTRPG livestreams that model protocols of care and accountability through communication. We offer the account and analyses here to emphasize the need, and as a possible starting point for, the development of flexible, situated practices and protocols which embody the values of care and accountability for TTRPG players and GMs wishing to contribute to cultural change.

–

Featured Image is “Reflections.” Image by Peter Castleton on Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Cite This Essay: Klein, Sarah, and Gerald Vorhees. “It’s All Fun and Games ‘Till Somebody Loses an I: Ethnomethods of Bleed.” Analog Game Studies 11, no. 4 (2024).

–

Sarah Klein is an assistant professor in Communication Arts at the University of Waterloo. Her research centers on how methods travel across time and space. She is interested in play in/as method, including studying the aesthetic, theatrical, and craft modalities of science, and amplifying the empirical capacities of play, art and craft. Her current research takes an ethnographic and ethnomethodological approach to think through and intervene in everyday scientific practice, as well as using ethnomethodology and STS to reconsider and reconfigure practices of reading, performance, and play.

Gerald Voorhees is associate professor in the Department Communication Arts at the University of Waterloo. He researches games and new media as sites for the construction and contestation of identity and culture and has edited books on masculinities in games, feminism in play, role-playing games, and first-person shooter games. Gerald co-edits Bloomsbury’s Approaches to Game Studies book series and was managing editor of the Gender in Play trilogy in Palgrave’s Games in Context book series.