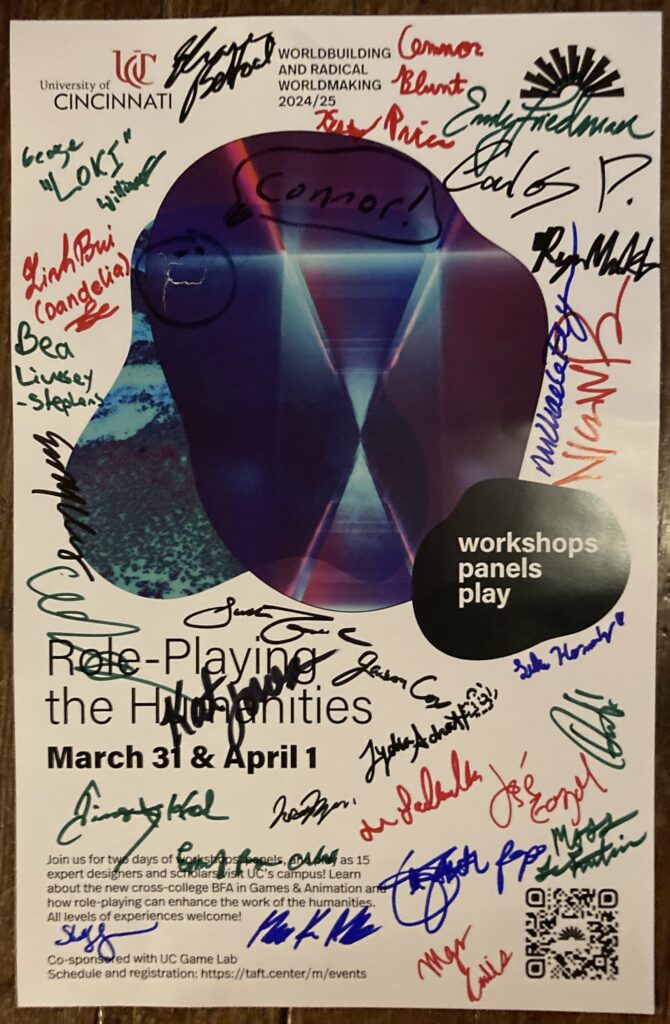

This collaborative, retrospective essay weaves together the reflections of fourteen participants at the Role-Playing the Humanities event at the University of Cincinnati (UC) on March 31 and April 1, 2025.1 The symposium brought together students, faculty, and administrators with expert designers and scholars of role-playing to think about how role-playing can enhance the work of the humanities and to explore the worldbuilding and radical worldmaking possibilities of role-playing games.

* * *

In 2015, David Jara and I hosted a few role-playing game scholars from DiGRA (Digital Games Research Association) at the University of Heidelberg for a Role-Playing Games workshop sponsored by the university. If I recall correctly, participants besides David and myself were Kat (Castiello) Jones, Felix Schniz, Jerôme Larré, José Zagal, David Simkins, Annika Bohrdt, and several other German participants. There, we gave a few lightning talks but chose to focus most of our time on serious interpretation of play materials and live, in-person role-play among the participants. It was a gaming convention for academics, or an academic seminar that took play very seriously. Based on others’ prior successes at the Knudepunkt and Living Games 2014 conferences on LARP as well as my own at the 2014 and 2015 DiGRA Role-Playing Summits, we surmised that better networking and interchange would happen if the participants played relevant games together, rather than just talk about them at each other (which is what academic games conferences are usually like). Thus, the “Heidelberg model” was born. Role-playing workshops should embrace both scholars and practitioners, meditations on role-play as well as role-play itself, and open, inclusive environments that nevertheless seek to advance ongoing conversations, rather than re-invent the wheel. I continued to build on this model via a few follow-up events: the 2019 DiGRA Role-Playing Summit in Kyoto, Japan as well as the respective 2023 and 2024 University of Bonn workshops on Role-Playing as Media and Agency and Asymmetrical Dependency in Role-Playing hosted by Adrian Hermann and co-organized with Emily Friedman.

“Role-Playing the Humanities” was simply me bringing the Heidelberg Model home to my own institution, the University of Cincinnati. My goal was to gather together several different folks working both domestically and abroad on this area in a conversation that would also invite local students and faculty to join. The physical “gathering” was crucial to me, for pandemic-era global isolation has kept us from the kinds of productive, casual, and serendipitous togetherness that unfortunately only an in-person gathering of fellow human practitioners can bring. When the Taft Research Center had the relevant thematic cluster for 2024-2025 “Worldbuilding and Radical Worldmaking,” I leapt at the chance to bring the kinds of role-playing scholars and practitioners who, indeed, are helping envision a better world.

The “Humanities” portion of the event title I see as a cry for help. Humanistic inquiry is threatened everywhere. Humanistic analysis and discussion of texts brings us together, whereas regimes of power seek our fear and isolation. Moreover, every humanities discipline, from linguistics to history, has something to gain from role-play as a medium. If we want to re-configure and revitalize humanities engagement, we must work from the fundamentals, including the act of character embodiment and the mechanisms that keep us safe while we do it.

“Role-Playing the Humanities” helped us validate our work through playful engagement, and I hope the conversations and play sessions that took place at the University of Cincinnati in Spring 2025 continue to resonate for years to come. As director of the UC Game Lab, I could not have done this without the generous support of the Taft Research Center, the A&S Associate Dean of the Humanities Jay Twomey, and my brilliant, capable student assistants Connor Blunt and Kasey Price.

—Evan Torner, University of Cincinnati

* * *

Wow!

Really?

Cool…

As I sat there, I thought to myself what a mixed bag of academics I found myself invited to join. All those Professors, published authors and other assorted academics I found myself sitting around a big table with, here to talk about role-playing in education. Many self-pinches ensued.

We were really convened to talk about role-playing in school? Was this all a wonderful, if a bit confusing, mirage? We were. Laboring in Gary Gygax’ basement 50 years ago, we never, in our wildest dreams and speculations, saw this coming. We were concerned with making a very skimpy payroll, and keeping our small job-print shop paid on time. We were hoping to make converts to role-playing, as a hobby. It was supposed to be fun, a trifle, an amusement. We set out to change gaming, never did we realize, in those early days, just how powerful a social tool we were creating. What we had designed for a table full of players had grown into a games with unlimited numbers of players, in college.

I came away with a sense of just how cool all of this is. We didn’t set out to, back in those heady days, change society. We didn’t plan to seep into the culture so thoroughly, but we did. We have. When I see all this, how can it not be cool, very cool?

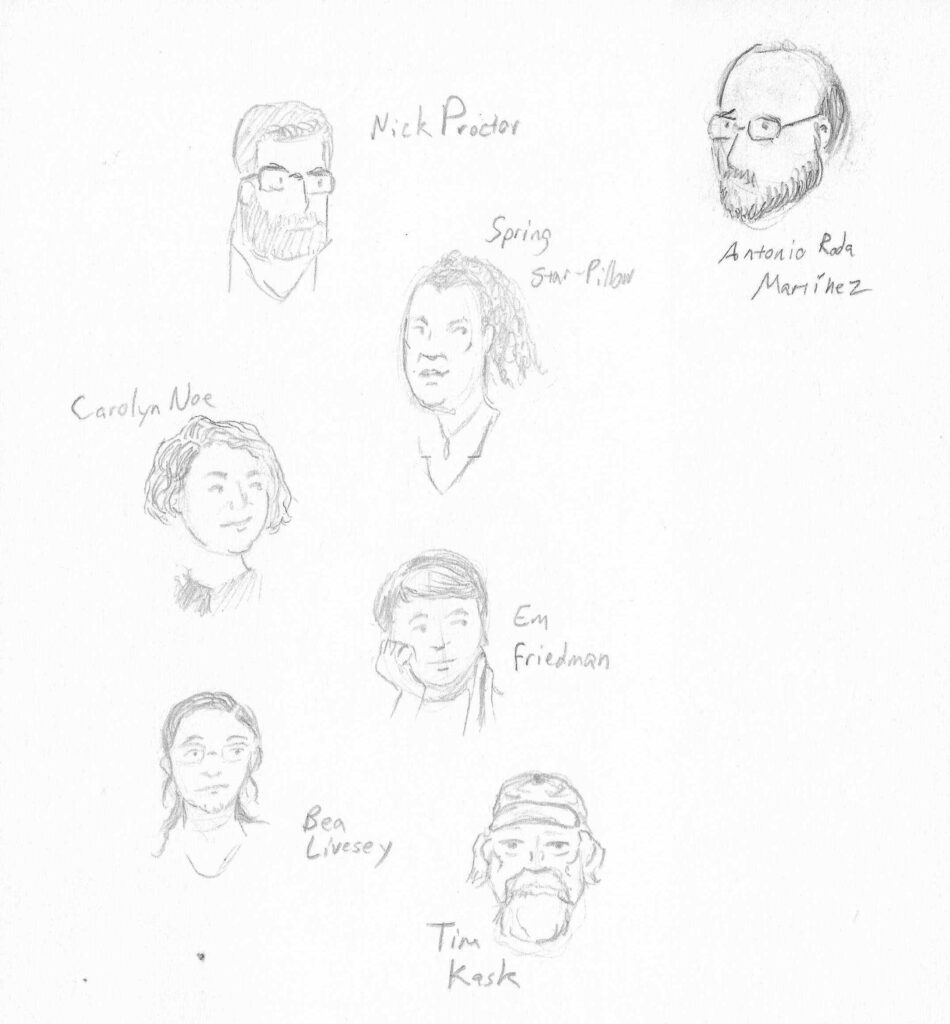

—Tim Kask

* * *

Balancing one’s positionalities as a player and a scholar is common in TTRPG scholarship. Without actually playing first, it’s difficult to theorize experiences that are both embodied and also tend to involve a plethora of game mechanics and play conventions. Foundational concepts from Gary Alan Fine’s Shared Worlds, Daniel Mackay’s The Fantasy Role-Playing Game, and Jennifer Grouling’s Creation of Narrative in Tabletop Role-Playing Games all explicitly come from these scholars’ deep experience playing and observing TTRPGs long before writing about them.

Why recap this? Because it’s also how I’d summarize my experience at Role-Playing the Humanities—participating in this practice in real time alongside a stellar troupe of TTRPG designers, scholars, players, and interested parties.

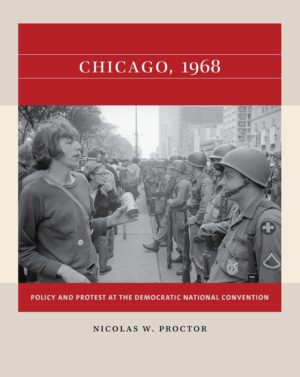

I was struck by how panels and roundtables were fluid, with conversational strands being introduced by speakers, but conversations then carried by the whole party. Likewise, it was incredible to both connect with and also play alongside designers whose work really brought me to this point: particularly Nick Proctor and Michaele Ferguson from Reacting to the Past, the pedagogical LARP that kicked off my own experience in higher education some fifteen years ago, and also Tim Kask, who in between talks very graciously answered many questions about Dragon magazine, Appendix N, and second edition AD&D.

In the case of Reacting, this pedagogical tool is one I remember fondly from Honors courses at Cleveland State University (thank you, Dr. Jo Gibson!). I have been looking for ways to introduce Reacting to my department, and hearing about design, playtesting, and reception from the team was such a good peek behind the curtain. Elsewhere, I’m both an avid D&D player and also forever tweaking the syllabus for my literature course ENGL 2235: Fantasy—Dungeons & Dragons. Therefore, Kask’s memories and perspectives of these core D&D texts are literally invaluable.

Finally, I’d be remiss not to mention that we had several gaming options per day to could choose from, but I played two in particular: Jason Cox’s Five Hundred Year Old Vampire, a collaborative artifact-making TTRPG, and Tim Kask’s impromptu “original” D&D game. Both were such different, fun exercises to participate in as a scholar-and-player playing alongside other scholar-players!

—Maria K. Alberto, University of Utah

* * *

The Role-Playing the Humanities event at the University of Cincinnati was a deep dive into, among other things, how role-playing games can help us make meaning. And in a time when nothing seems to make sense, this experience was one of the most emotionally and intellectually rewarding conferences I’ve ever participated in.

In particular, I appreciated the emphasis on play throughout the two-day event: casual play in our off time, playtesting colleagues’ games and providing feedback, playing the Reacting to the Past game Chicago 1968 or Five Hundred Year Old Vampire, and, of course, ending with the Shadow Scar one-shot, run by the incomparable Cody Pondsmith (whose agility and sense of humor as a GM were incredible).

These playful experiences anchored us, reminding us why we love studying games, why we incorporate games into our curriculum in meaningful ways. Playing 500 Year Old Vampire resonated with me in unexpected and emotionally evocative ways (as is so often the case with roleplaying). In this two-hour session, we roleplayed as vampires mourning their loss of community, unpacking generational trauma, and attempting to survive. We, the players, who before sitting down at the table, had been virtual strangers, folks we had seen on our Zoom screens in conferences past or maybe shared a table of contents with, but had never actually met, wrote moving letters to one another about the unexpected twists and turns of our characters’ lives. Strangers yesterday, now we were nearly in tears over our characters’ (dis)connections, crafting and creating representative objects of our shared stories. This playthrough was truly emblematic of the core principles of the Role-Playing the Humanities event, focusing on being welcoming, encouraging, and collaborative.

—Shelly Jones, SUNY Delhi

* * *

Evan Torner has been helping me become the scholar, gamer, and person that I aspire to be ever since I first entered game studies, and I am thrilled that I got to share his gift of the Role-Playing the Humanities event with so many new friends and colleagues. He crafted it so that instead of a space wherein I was either talking at people or being talked at, we were given the opportunity to construct the rarest of things to find in an academic setting: meaningful discourse. Whether talking over hotel coffee in the morning, pontificating at the Taft Research Center, chatting around the games we all loved, or telling stories long after I knew I should have gone to bed, there was never a time when I was not engaged and excited by this discourse.

I also received the gift of sheer terror in the form of my first actual play. As an arts professor I often critique the work of students, but I am rarely up close and personal with an audience for my own work. The result, in Graham Walmsley’s terms, is that I don’t always remember what it is like to “play unsafe” the way that I ask my students to.2 Being watched by my peers brought the game “closer to home”3 and made a game that was ostensibly for an external audience into an intensely personal experience. While I enjoyed myself, the memory of wrestling with my self-doubt while the audience looked on and the camera rolled spurs in me the empathy for artists of every media and at every level that I sometimes fear I may lose. It is a treasure that I hold close to my heart.

—Jason “Doc” Cox, The University of Toledo

* * *

My favorite part of Role-Playing the Humanities was learning about aspects of analog game studies that I don’t otherwise have the chance to dive deep into—such as how roleplay can be used in history classes. It was really special to have people working in so many different specializations in the field and to hear their perspectives.

Specifically, I wanted to contrast the fact that analog RPG studies is such a young field yet there is already such a wide intersection in the topics, interventions, and discussions. In fact, what surprised me is that there is such a big gap between TTRPG scholars and non-scholar TTRPG fans. I was reminded that the vast majority of non-scholar TTRPG players aren’t involved in academic circles, and that there’s kind of an observer’s paradox about how knowledge of the academic dimension of TTRPGs can affect the way we play. This tension, of course, isn’t inherently good or bad. I mean there is a nuance to it because the interface between playing as a hobby and playing for research can be blurred. With that said, I hope that any TTRPG player who does decide to read analog game studies is able to better understand their experience and understand what they derive from playing without losing the fun they have.

For example, I really enjoyed playing Jason Cox’s Five Hundred Year Old Vampire and learning about how to use epistolary games to explore history, how fictional accounts can still be really good pedagogical tools. My particular group looked at Inuit history. My character was wrestling with the mortality of the people around them and how this meant they weren’t able to sustain their community. The crafting aspect of the game encouraged me to think about the “unwritten” messages that the keepsake item could communicate. I was also interested in the interface between the written word and the crafted object. In my character’s case, a significant aspect of their personhood and personality was their hair: if it was cut, it would immediately grow back. Therefore, one of the keepsake items I made was a lock of my character’s hair wrapped around a candle to think about my character’s relationship to time.

Overall, I had a wonderful time at Role-Playing the Humanities. It has been a decade since I had visited the United States, and it was really interesting, even surprisingly fluid, to reorient myself. I got to experience Panera Bread and to have Goldfish again. (I took a bunch home). I also really enjoyed getting to get together with Analog Game Studies folks in person and playing Edmond Chang’s card game.

—Beatrix Livesey-Stephens, Abertay University

* * *

Attending Role-Playing the Humanities at the Charles Phelps Taft Research Center was both a scholarly and personal turning point. The event foregrounded how TTRPGs can embody the values of the humanities—especially empathy, complexity, and negotiated meaning. As someone researching screenwriting pedagogy through analog games, I was struck by how conversations continually circled back to role-playing as a practice of co-constructed knowledge.

During the worldbuilding panel, I reworked my initial contribution: a journey from the distinction between our reality as a Primary World and the fictional Secondary Worlds we create,4 through how audiences navigate them based on perception and expectation,5 and ending with the role of genre and tone as shortcuts that facilitate access to these worlds by framing them as coherent and believable.6

But, here, I’d rather focus on what I received from the other participants:

- Watching Tim Kask speak about early classroom RPGs; playing D&D alongside Edmond Chang, Maria K. Alberto, and George “Loki” Williams.

- Receiving incisive feedback from José Zagal and others on CONsensus, my GM-less game about asymmetrical power and fragile agreements, affirmed for me the value of games that interrogate both narrative and social structures.

- Role-playing is about learning the importance of choices, and I had a difficult one to make between two games I’m considering for classroom use: Nicolas Proctor’s LARP Chicago 1968: Policy and Protest at the Democratic National Convention (2022) and Jason Cox’s TTRPG Five Hundred Year Old Vampire (2024); I ultimately chose the latter drawn by its integration of writing and artistic creation—elements I’m eager to adapt to my Ph.D. thesis.

—Antonio Roda Martínez, Universidad de Sevilla / Centro Universitario EUSA

* * *

It was a whirlwind. I learned too many things and now I have to sort through them all. Whirlwinds—the metaphorical ones—can be useful as they shake things up and push you towards reassessing your assumptions and understandings. So, I’ll focus (unfairly, because everything was incredible) on a single thing that stood out for me.

Learning about and playing a Reacting to the Past game challenged my understanding of worldbuilding and role-playing (see https://reactingconsortium.org/). I would have said that historical role-playing’s proximity to re-enactment makes it a context largely anathema, or at least hostile, to worldbuilding. We should not “worldbuild” the past! However, I learned about the “corridor of plausibility,” a concept describing an agential space for worldbuilding within historical constraints. The corridor of plausibility reframes the historical role-playing activity by giving players freedom and alibi to roleplay such that they might build a past different from what occurred: it is ok if things do not happen in a “historically accurate” way. Simultaneously, it signals where the roleplaying should not go—things may be different from what happened, but they should remain plausible. I was especially appreciative of learning about the iterative design process used in creating Reacting to the Past games and its emphasis on empowering game designers to, through their design choices, create a corridor of plausibility both wide and narrow enough for learning.

The corridor of plausibility is a powerful concept for achieving pedagogical goals. I think it is also useful for thinking more broadly about worldbuilding at the edges. For Reacting to the Past games, the edge for worldbuilding is due to their educational and historical nature. But what are the edges of worldbuilding that exist in other contexts?

In all? I am incredibly grateful for the invitation and opportunity to participate and I am grateful to all the sponsors and organizers. Thank you!

—José P. Zagal, University of Utah

* * *

I have been very lucky to work with Evan Torner over the last few years bringing designers, academics, and thinkers together to play and think about TTRPGs in intentional communities. With Professor Adrian Hermann of University of Bonn, we hosted gatherings in Germany in 2023 and 2024, and last October our “Big Bad Academy” track at Big Bad Con paired career researchers with respondents from across the TTRPG field: designers, makers, performers, and more. No event is perfect, but something always emerges that we could not have planned for, and that generates new insights, which is why I study roleplaying games and Actual Play.

In fact, when I had surgery rescheduled to just days prior to this event, my first question to my care team was whether I would still be able to attend. I am on leave to write my book on Actual Play, and this gathering was one of only two spring events I had let myself schedule because I knew it would be a space to reflect, fill my cup, and get back to book writin’ with renewed vigor. Thanks to help from family, we made the eight-hour trip from Alabama to Ohio, and I was glad I did. Every RPG gathering or event is a little bit different, shaped by who is in the room. This group thought more pedagogically than others I’ve been a part of, thanks to the presence of University of Cincinnati students as well as the Reacting to the Past designers.

I’m preparing to follow in Evan’s footsteps and hopefully organize a similar meeting at Auburn University in the coming months. It’s a precarious time to do this work and make plans, but I am reminded why we do so.

—Emily C. Friedman, Auburn University

* * *

As part of the Role-Playing the Humanities event, my Diversity in Gaming class attended the session on Worldbuilding. While I personally found the session helpful for my own teaching, what I found even more pedagogically impactful was student reactions to this session on our weekly discussion board. The Worldbuilding session, which included a discussion of games in the classroom, how to engage with historical themes in games, and safety and calibration tools, prompted my students to engage with these themes in complex ways.

For example, my students offered different perspectives about how to introduce games with mature or sensitive themes into a classroom, grappling with the limitations of safety and calibration tools, but also the potential to shut down important discussions by excluding certain themes or games from classroom play. One of my students stated this session had caused them to re-examine their assumption that the exclusion of oppression in games was always the most inclusive option. Finally, several students discussed introducing the safety and calibration tools discussed in the session into their own play communities. They examined potential difficulties in introducing these tools into established gaming groups but encouraged their fellow students not to compromise their boundaries for play.

Not only did the Worldbuilding session introduce my students to new perspectives about these topics; it also encouraged them to engage with the complexities of these issues (several students explicitly rejected simple or “one-size fits all” solutions), and empowered them to take these new perspectives beyond the classroom, all important learning goals for my course.

—Katherine Castiello Jones, University of Cincinnati

* * *

The Role-Playing the Humanities conference was not only fun but also demonstrated how complex and generative the term “play” was among scholars, gamers, and game developers. While I mostly study play in relation to digital game studies, going to this conference reminded me of my own roots in analog games and how play unites us in the way of research but also in community. I came from a family of gamers where I played Dungeons and Dragons when I was younger, and even then, I recognized how ambivalent role-playing was. Take that to every analog game and there will be endless stories that reveal so much about us and society from playing together. During the conference there were sessions dedicated to playing games together. Truly, it was nice to see play in action, and it was interesting to navigate how others play. I was also able to play games where I had the opportunity to talk with the game creators! What resonated with me was how close the play felt. Perhaps it was the literal proximity with others, the vibe, or maybe I need to get out more, but this type of close-knit playing was something I personally enjoyed, but it is also an aspect I wish to configure more in my own research work. Of course, I love researching digital spaces, but the format and discussion of the conference reminded me of the importance of considering the analog when researching the impact of play. In a political climate that is very tumultuous, what united this conference community was envisioning the various routes to a more playful future.

—Luke Hernandez, The University of Texas at Dallas

* * *

The Role-Playing and the Humanities event was such a delight and I am so thankful for the invitation from Evan Torner and the University of Cincinnati!

Something that really struck me over the course of the event was just how much of a game changer (forgive me) it was to be interacting with practicing game designers. Listening to and (be still my heart!) playing alongside amazing designers like Tim Kask, Loki Williams, and Cody Pondsmith was so invigorating and inspired an embarrassing number of ideas for new research projects, new venues to encourage student engagement, and new ideas for special issues of AGS. It also made me realize how important it is for us as academics studying tabletop role-playing games and the communities surrounding them to cultivate relationships with creators and fans. Establishing trust and rapport with these stakeholders is vital to doing this work, and so I am grateful that our annual conference, Generation Analog, has always been a venue to bring researchers, creators, Actual Players, and fans together.

And finally, the event drove home for me once again the importance of experiential learning, of playing excellent games like Jason Cox’s Five Hundred Year Old Vampire, Nick Proctor’s Chicago 1968, and Cody Pondsmith’s Shadow Scar. Playing these games did so much to enrich the discussions that we were having around them and helped me to articulate questions that I would have never likely have thought to ask if I had merely read through the games by myself. The process really made me re-commit to dedicating lots of time in my class to play (and also to debriefing students about what they experienced afterwards).

Congratulations to Evan and to the Taft Research Center on a phenomenal and productive event!

—Megan Condis, Texas Tech University

* * *

The Role-Playing the Humanities conference fittingly took place in the lull between two major storm systems that brought heavy rains, flooding, and tornadoes to the Midwest. In the midst of a stormy period for the humanities, for higher education, and for the US and the globe, the conference gave us a much-needed respite to think and play together.

What has stuck with me in the weeks since we all met are our conversations about how role-playing can cultivate our students’ capacity for agency. Reacting to the Past games were my gateway drug into the wider world of role-playing. I’ve been using them for over a decade to teach my students political theory texts, but early on I learned that my students were also learning through play how to do politics. I found it energizing to meet other academics in Cincinnati who—while they are using very different kinds of role-playing games—are also thinking about how to teach political agency and the capacity to resist democratic backsliding through play.

The challenge I confronted at the conference is that, while games create the conditions for students to learn resilience and resistance, we do not have a way to guarantee that they will take these lessons from play. We discussed different game designs that can highlight (such as Melissa Spangenberg’s A Single Man of Good Fortune) or obscure (like Storybrewers’s Good Society) power relations. Perhaps one solution is to design games thoughtfully to bring hierarchy and power to the foreground of play. Yet even then, our students can be disengaged from play, or conversely, so engaged in playing that they do not make the connection between games and the world they live in.

Looking back, I wish I had taken more opportunities to talk with people who use very different styles of gaming in their classrooms about this issue: how can we improve the games we use, or improve how we teach with games to increase the likelihood that our students will learn the skills and ways of thinking we wish for them to cultivate in these stormy times? I hope to continue this conversation with you in the months and years to come.

—Michaele L. Ferguson, University of Colorado, Boulder

* * *

Role-Playing the Humanities was like sleepaway camp for analog game nerds. The minute I arrived at the hotel on Sunday evening, a storm brewing at my back, I knew I was in for an experience, a happening. Those that had arrived earlier in the day were gathered in the lobby sitting area, eating snacks, knitting, crafting, and chatting. From that moment on, we would spend nearly every waking hour together talking about games, pets, life, work, writing, designing, teaching, our hopes and dreams. Each day was intensive, special, even startling. I remember sitting across a table from the inimitable Shelly Jones, with whom I have worked for nearly five years at Analog Game Studies, and suddenly asking, “Is this the first time we’ve actually met in person?” Other standout moments include the discussion of using role-playing games for teaching, engaging students, and offering innovative experiential learning; the session on worldbuilding and creating community, collaboration, and connections; the deep dive into actual play, live play, parasocial relationships, gamer celebrities, and fan labor; and especially, the in-between times like getting breakfast or dinner, walking to and from the venue, and looking for coffee or snacks during breaks.

Of course, my favorite parts of the three days were when we got to play games. Playing Jason Cox’s keepsake game Five Hundred Year Old Vampire was thought-provoking and fun even though my group took things to a dark, emo place in the first round. I particularly enjoyed the making of artifacts, the artsy-craftiness of the game’s storytelling mechanics; it really allowed us to visualize and materialize our ideas and role-play. I really wish we had the time and opportunity to play more games; I really wanted to experience Nick Proctor and Michaele Ferguson’s running of Chicago 1968, a Reacting to the Past live-action role-playing game. Lucky for me, I did get to play old school Dungeons & Dragons with a small group game-mastered by living legend Tim Kask, who noted at the start that we were playing pre-first edition rules; I was Wesley, a cleric, in a group of mostly rogues it turns out. I am also deeply fortunate and honored to be included in the live play of Cody Pondsmith’s Shadow Scar, a new tabletop RPG from R. Talsorian Games about multiverse-hopping, ninja-inspired agents; I played a woman named Aisha, a shy but aristocratic information and secret gatherer. I rarely get to be on the player side of the table. For this closet performer, it was amazing to be a part of a committed group of role-players and strangely exciting to play in front of an audience. Finally, I am thankful to all of the participants that I cajoled into playing my cooperative, semi-autopoietic card game Archaea: Bane; the game has been years in the making and nearly ready to be released to the world. It was great to get folks’ reactions to gameplay and to feel supported by fellow designers, scholars, and players whose expertise is undeniable.

But, as with all good things, nerd camp had to come to an end. I do hope that we can build on what Evan Torner and others started. As I wrote elsewhere, “I sense and see a need in the world for new games, different players, and better worlds. Against fear, against despair, against violence, against injustice, against devastation, games can encourage hope, possibility, change, imagination, and curiosity…” We all need this, the humanities need this, and the world needs this. Here’s to Role-Playing the Humanities Second Edition and beyond!

—Edmond Y. Chang, Ohio University

–

Featured image by Edmond Chang. Used with permission.

–

Abstract:

This collaborative, retrospective essay weaves together the reflections of fourteen participants at the Role-Playing the Humanities event at the University of Cincinnati (UC) on March 31 and April 1, 2025.

Keywords: conference, postcards, TTRPG, role-playing, humanities, University of Cincinnati, pedagogy