The adventure begins…

Emerging from our games cupboard with a lately neglected copy of Lord of the Rings by Reiner Knizia 1 I aim to challenge myself two-fold; by attempting to cleanse a world of pernicious evil and to explore whether I can reconcile Middle-earth with my feminisms. Identifying myself as a feminist killjoy, 2 I feel my strongest embodiment and public manifestation of killjoy moments appear as I embrace my gaming feminist killjoy. The gaming space allows me to challenge the status quo and explore different approaches to knowledge (re)production and representation, within delineated boundaries which allow many things to be said that I would perhaps feel timorous of exploring in a different context. By examining and questioning modes of knowledge and representation in this manner, the foundations are set in which I can articulate and share my perceptions, engaging in dialogue with contemporaries and exploring the ways in which we take such discussions outside of the gaming space, into our private-public lives.

My focus in this essay is to analyze Knizia’s Lord of the Rings, exploring the extent to which a game involving a substantial amount of thematic and trans-textual content, as well as novel play (cooperation), can offer multiple ways of considering and challenging knowledge (re)production and representation specifically linked to patriarchal structures. Lord of the Rings has been cited as one of the first popular collaborative games (released 2000) designed for a mass international English-speaking audience.3 Knizia aimed to create a game with the power to overcome tensions between individual rationalities, and to encourage collaborative working with positive effects on the overall gaming group.4

My analysis occurs in a particular time and place, following feminist modes of enquiry in which I read it from my own situated perspective 5 and imagination. 6 As my feminisms are not separate from myself, the way I play and engage with games is already invested in feminist frames of knowledge critique. Whether this critique is undertaken purposefully or not (i.e. as research or casual in-game commentary), I embody my gaming feminist killjoy to create and question knowledges of the world (through gaming) as informed by my own life experiences, beliefs, engagements with literature and other forms of cultural ‘knowledge’ as well as my imagination. I therefore carry with me a knapsack of ‘resources’ through which I dive to sustain myself throughout the gaming journey. By employing autoethnography, scribbling notes as I play, I aim to bring method to my thought processes, articulating my experiences and insights in a manner which brings both the pleasures of play and academic thought together. In addition to engaging in discussions regarding the above I also imagine myself to be in dialogue with Tolkien vis-à-vis the game board, crossing temporal-spatial boundaries,7 bringing Middle-earth and its narrative into our own troubled and unsettled contemporary climate. The decisions and problems facing the characters of Middle-Earth, whilst they journey along our tabletop, could be viewed as symbolic of wider issues and political maneuverings outside the game, offering the potential for critical insight into our own worldmaking machinations.

Theoretical tools: Resource knapsack

A key framework for this analysis lies in juxtaposing differing concepts of space and time and how these can be inhabited on various levels. ‘Western’ social space has often been seen as colonized by the logics of white normativity and heteronormativity 8 and this seems likely to include gaming spaces (although there are arguments this notion may be complicated by Western neo-liberalist thinking which would posit gaming as a sub-cultural/non-normative phenomena. 9 10 Indeed, both digital and analog game research supports the notion that gaming spaces, especially within the West, have traditionally been claimed as the domains of white, self-declared heterosexual male gamers,11 12 and whilst such spaces are currently undergoing reconfiguration, opening up analog game spaces to a wider audience via board game cafes, Kickstarter programs, online board gaming communities, and Covid-induced recreational opportunities, there is still a threatening undercurrent of hostility towards those challenging the white, heterosexual, male dominance of this space.13

By inhabiting and focusing on a particular game space and its subsequent knowledges and representations through a feminist lens I intend to deviate from such a colonization of the space and to explore alternative forms of experiencing space and gameplay. I do this firstly by imagining the space as heterotopia.14 By this I mean space which deviates from dominant normative space in a neo-liberal world – it offers a seemingly non-productive place from which to critique existing social arrangements. It also acts as a space where varying configurations of knowledge and representation are present, drawn from transtextual parameters and player backgrounds. We draw from our own knowledges, recognizing that the game space and content mirror and enact many of the social issues of our own realities regardless of the game’s mythological origins.15 By thinking of the game space as a heterotopia, the gaming table denotes the beginning and end of our immediate immersion in the game and allows me to situate myself within a particular place where I can examine various disidentifications I have with the game as it progresses. In this way whenever I come up against something I detect as patriarchal I can stop and consider it, discussing such aspects with my gaming partner. We may experience and act differently in this space according to how we approach and play the game, and hence I expect a lively gaming session to occur.

Furthermore, moments of disidentification, defined by Munoz16 as negotiations of majority culture which are transformed for their own cultural purposes (through performance, survival, activism) rather than as staunch alignments or exclusions associated with certain ideas/identities, are also highly influential in highlighting the various ways I play and move across the gameboard.

Within the heterotopic space of Lord of the Rings, disidentification with both the narrative and the choice of characters available further emphasizes and reflects my feminist identity and following critique. By recognizing disidentification as a strategy for challenging knowledges and representations, I am able to transform and comment upon various narratives embedded within the game and to consider these outside of the parameters of the gamespace itself i.e. in writing up this analysis. Disidentification allows me to see myself juxtaposed with the character I must embody, as well as the narrative(s) I find myself within, able to recognize differing and contradictory world views I hold which de/construct gameplay as I traverse across the gameboards. For example, I may not identify with the characters or narrative in Lord of the Rings but neither do I turn from them completely; I disidentify with certain aspects such as the patriarchal and male-dominant world it seems to uphold but yet recognize the collaborative ethos underpinning the narrative which works across difference to create alliances for triumphing over oppression. I see an ethos and commitment to something I want to embrace but it is located within a context that does not sit right with me.. In a motion similar to that undertaken by Norma Alarcón,17 of thinking through the ways in which one’s own subjectivity or ‘voice’ cannot be arrived at through a single identificatory category (we embody multiple subjectivities that live in resistance to competing notions for one’s self-identification or allegiance),18 I am grasping and working through dominant and marginal spaces to find the ideal which reflects my own experiences, wishes and desires that I have yet to find. I thus write my disidentifications into the game space and contribute to challenging and transforming it through embodying and subverting highlighted constructed knowledges. By disidentifying with certain representations and narratives within the game, I also bring in my own political imaginations,19 20 challenging and subverting a world which continues to call for normative engagement and universalizing conceptions of certain knowledges (i.e. heterosexual love as the norm;. Indeed, these are not new challenges as researchers, creators and gamers have been highlighting such issues for years; the continued universalization of certain dominant knowledges prevails in many forms across gaming territories.21 For me, the game space provides both space and time to delve deep into myself and to (re)emerge in the world (both gaming and non-gaming) through a recreation of myself and a restructuring of society that is informed by a continuous learning process constantly encouraging me to challenge the ways I live and know.

I embody the tools above as I play through the game, reflecting on my positioning and affective responses both during and after the game. Entwined with analyzing this particular gamespace and embodiments of play, the visual and textual elements of the game also inform my perception of Lord of the Rings and how I interact with my gaming partner; these elements, preliminarily glanced during game set up and play, induce reactions linked to disidentifying moments in which I consider the power of certain representations in conveying and challenging assumed knowledges.22 23 By also highlighting these elements throughout the analysis, I deploy an ethic of embodiment which further conditions my creative and political insights into the game and wider societal considerations. As a gaming feminist killjoy in this heterotopic world, I experience multiple contestations of meaning located within the game, combining and working across my emotional, affective and discursive reactions to the narrative. As my partner and I engage in dialogue during the game, I am also aware that we embody different reactions to certain scenarios and elements of the gameplay. Personally, I find this provides a heightened immersive experience of the game, where the gaming world and outside world (or what Paul Wake terms the ‘meta game’)24 coalesce to form my own unique current habitable reality (neither purely ‘in’ the game world or ‘out’ of it). I am immersed in a world of my own making.

Ultimately, I consider the game to offer a mirror of the ‘non-gaming’ world (i.e. it’s patriarchal world structure and potential for collaborative efforts to bring about positive change) and for myself to mirror the game outside of its parameters in subtly revealing ways (i.e. such as striving to ensure I work collaboratively, establishing alliances, in continuing struggles against misogynist and patriarchal power relations in ‘the real world’). So how does this all converge when I play? What does such an analysis have to say about knowledge (re)production and representation? What exactly can a feminist critique of Knizia’s Lord of the Rings (2000) look like and what is the point? In the following section I aim to answer these questions and offer playful feminist insights based on my own experience of play.

A Playful Analysis: Journeying to Mount Doom and hopefully not our own

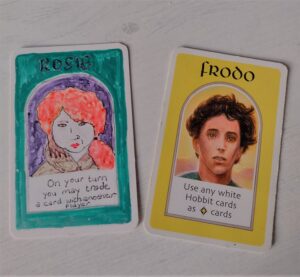

My gaming partner has willingly agreed to participate in adventuring through Middle-earth. The scene is set; an early spring afternoon, sunlight streams through the second-floor window onto a dining table transformed into a mini Middle-earth. ‘Sauron’ is placed on square ‘13’ of ‘15’ (‘Hard’), assuming we will work well together and that defeating evil will be but a small trial for us. For the purpose of a two-player game the rules dictate Frodo and Sam to be the available hobbit pieces (all playable characters are hobbits) as they are envisioned as integral members of the fellowship. Randomly allocated I become Frodo and my partner becomes Sam. Frodo’s special power lies in being able to utilize cards as ‘any’ resource whilst Sam moves only one along the corruption line after rolling the dice (players generally move up to three spaces). Three other hobbits are also available for larger games; Merry, Pippin and Fatty. As the fellowship, depicted by Tolkien25 includes a combination of hobbits and other races, the game reflects only a limited choice confined to hobbits. One curious thing which strikes me is that Fatty is never part of the fellowship, playing only a minor role at the beginning of the novel. I question whether a different hobbit could have been chosen instead, for example, Rosie Cotton who makes Sam her husband later in the story: the character with a feminist approach to the adventure who also draws on an ability to help others when in need and also to request their help, encouraging a relationship of reciprocity. The inclusion of blank cards, albeit without a single reference to their inclusion in any of the game’s paratext, encourages me to think the designer would welcome creative additions from the gaming community. There is the potential to create and think through various experiences through utilizing these blank cards – not just in terms of introducing a non-male playable character to the game, but also to think about the various subjectivities that form and propel us through life. Whilst I recognize my own analysis is fairly limited in scope focusing on patriarchal relations and thus to some extent gender binaries (employing Spivak’s26 use of strategic essentialisms), there is the potential for a larger, more intersectional analysis to be embraced as space and time permit a more extensive research project. Using the blank cards to create a whole host of playable characters, based on players’ own subjective experiences could be a fine starting point for such research. For now, however, I have created a character that I now more closely identify with and look forward to channeling my embodied gaming feminist killjoy through this character during the game journey. As I ‘become’ Rosie, I enter into the game space as an embodied, ‘moving’ being, a cyborg-fictional character not completely myself. I test myself by adopting this hobbit persona, keeping in spirit (to a degree) with the storyline, and also by challenging Rosie’s fictional representation as a passive ‘home-maker’ in the novel. I re-write her with agency and control; adventurous in myriad ways, happy and free in her choice of undertaking domestic work if she pleases, and always taking an active role in her life choices. I feel I can now represent, contest and invert female representation and the fictional reality of the novel, alongside an exploration of the ways in which the world of Middle-earth, a masculine-dominated world, embodies “institutional male chauvinism”.27 In this heterotopic ‘unreal’ space28 29 both my partner and I can ‘speak’ as our hobbit characters, commenting upon actions, ourselves, and the story setting, evidencing heterogenous and ambivalent positionings to the gaming narrative. With Frodo displaced I Sam, as embodied by my gaming partner, is my actual real-life husband.

Our past experiences of playing the game influence this particular gaming interaction as we are both aware of the rules and aim before we start. We were however intrigued to discover how this particular game would unfold knowing a feminist analysis was about to ensue which would critique a world not particularly known for its feminist values, depictions, or representations of female characters.30 Whilst Tolkien’s approach to female characterization has been interpreted by some as anti-feminist and by others as sensitive to nuances of female experience31 this ambiguity of interpretation would be an interesting facet to explore in our own gaming experience. Middle-earth is depicted as a very male-dominated and patriarchal world, feasibly reflecting Tolkien’s own place within and experience of society. The “War of the Rings” laying the foundation for the narrative has been defined in masculine terms as “a war of phallic edifices (contesting for, and threatened by, the power embodied in a symbol of the feminine, the ring).”32 The plotline of Lord of the Rings includes very few female characters and when they do appear they are not part of the fellowship but have specific roles often entwined with a reserved heterosexual love interest. Bearing these points in mind, alongside preconceived ‘knowledges’ we held linked to the transtextual parameters of the game and what we saw as its anti-feminist slant, once we became immersed in the gameplay we soon realized and recognized some rather unexpected Indeed, feminist collaborations seemed to appear all over Middle-earth as we played on; in hobbit dialogue, as we journeyed across the game boards, in our use of special abilities even if detrimental to ourselves, and in our sharing of resources. The game play seemed to reflect a need to build alliances across difference, recognizing and productively engaging with differences33 to enable survival through creativity and collaboration.

To further account for these somewhat unexpected and unsettling conclusions, I will briefly contextualize and indicate the key mechanics of the game. The aim as mentioned above, lies primarily in cooperating and collaborating with other players “[w]ithout cooperation there can be no success.”34 After ‘becoming’ our hobbit characters we journey to Mount Doom over four different game terrains/boards (Moria, Helm’s Deep, Shelob’s Lair and Mordor) in an attempt to destroy the ‘One Ring’. A ring-bearer takes charge of the ring for each board, decided by who amasses the highest number of ‘ring’ tokens during the preceding scenario. Events and obstacles are met along the way, dictated by turning over a game tile at the beginning of each character’s turn. These contribute to the slow corruption of the hobbits as they proceed towards Sauron along the corruption line on the main scoring board. Various decisions must be made, resources swapped and dialogue encouraged throughout the journey to ensure Sauron does not meet any of the hobbits; if he does the hobbit has been captured by evil forces and the game ends if they are also the ring-bearer. Evil triumphs. The game is won if the ring-bearer makes it to space ‘60’, rolls the dice and manages to cast the ring into Mount Doom without meeting Sauron or running themselves out of cards. All the hobbits must work together and will receive the same score at the end whether they meet Sauron or not.

To our irritation, we realized the power of Sauron and the power of the ring, which I saw as analogous to patriarchy and capitalism, were omnipotent and suffused the game from beginning to end. There seemed to be no escape from the clutches of either. Sauron moved closer to us even though we tried desperately to fight him through combining our resources, discussing how to approach our next turn(s) and making decisions about utilizing Gandalf’s ‘one-off’ powers to prevent certain ‘evil’ events from affecting one or the other of us. I saw this as an omen and mirror of society, aligning it with feelings of hopelessness in the face of adversity when everything one tries to do appears to make little positive difference. We both became despondent and dialogue faltered for a while, my partner becoming visibly grumpy and myself starting to act recklessly with regard to resources, wanting to try and overcome Sauron by myself to prove my worth and pretend bravado at this time. This offered an interesting insight into the affective dimensions of play35 36 and how it contributed to our thoughts of society outside the game and in relation to one another. Realizing we could not achieve our joint goal if we both continued to act in our own interests, we both decided to re-strategise and agreed that even if we lost we still had our collaborative relationship to hold on to and could learn from this attempt, perhaps better prepared for our next effective tackling of the patriarchal and capitalist inflected demons.

Such thoughts continued to flit around my mind as we continued playing. Alongside notions of collaborative play, I also detected a commitment to inclusivity in the implied collaborative efforts of the fellowship (through special cards which depict the non-playable fellowship characters) despite ‘racial’ differences (hobbits, elves, dwarves and ‘men’) and life experiences. However, this unfortunately does not extend to the actual characterization and representation of the gaming pieces and illustrations leaving something to be desired in combinations of non-male, non-white, and non-normative representation. In this sense I disidentify with the narrative and its representations; I recognize the potential of the game to highlight an experience of moving through a world following a feminist and communal mode of play, potentially linked to feminist ways of knowing and doing through the forming of alliances against oppression and the building of networks as feminist strategy – “[a]ccept that players will contribute at different times and in different ways during the game,”37 but I also feel an intense disidentification with the characters as they can be embodied and/or represented via their illustrations, all influenced by the story as created by J.R.R. Tolkien. By disidentifying in this manner I want to be able to encourage productive transformations of knowledge by engaging in dialogue that can transcend both time and space, to bring this narrative into 2022, inspiring representations which reflect a wide audience engagement with the story as indicated by its mass popular appeal. I do not believe Gandalf, as a wizard, has to be ‘white’, nor do I believe the female characters who are depicted must be white, thin, pale and delicately featured. Similarly, I also wish to challenge the ‘race’ of ‘Man’; a normative imagining to be contested as it further underlines the patriarchal sub-structures of Middle-earth society which by its substitution with ‘human’ (although also fraught with identificatory issues) would perhaps subtly reinforce a more (non)gender-balanced worldview. I wish to contest these representations and counter any arguments about remaining true to the original, as alterations to these representations would not compromise what some see as one of the greatest fictional worlds created by a western author.38 Greater visibility of diversity, in text, imagery and content to better reflect and invite existing and potential fanbases of Lord of the Rings (and of course any game or narrative) could contribute to a more inclusive gaming culture. I was pleased to note that Knizia’s rulebook avoided gender prescription by employing the direct ‘you’ throughout; in comparison The War of the Ring rulebook as analyzed by Jones and Pobuda39 utilized the male pronoun without exception, further highlighting the saturation of masculine representation pervading The War of the Ring. Whilst using non-gendered pronouns may be seen as a token or surface gesture, it does at least have the potential to encourage dialogue regarding representation in games and how this can be achieved for more productive transformations in the future. In many cases it is likely to go hand-in-hand with other inclusive practices and therefore move beyond the tokenistic to actually effect change.

With further recourse to the illustrations of the game, I find the images aesthetically pleasing and evocative, especially in portraying the various landscapes of Middle-earth. They do however also appear to reflect a male-dominated world, further consolidated by my knowledge of the narrative. Gandalf, positioned in the middle of the box cover, holds center-stage, an ancient, white wizened male, surrounded by pastoral forests and mountains. Sunlight streams from the right-hand corner whilst darkness descends on the left; I immediately consider the pejorative connotations Western society links with ‘left’ (‘dark’, ‘bad’, ‘evil’, ‘feminine’) and ‘right’ (‘good’, ‘masculine’, ‘rationality’).40 This is my interpretation of the box cover; I see it as a motif which runs throughout Western society and thus puts me on my guard as I play the game. In terms of character representation, especially in relation to the hobbits, there are no overt ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ features which can be discerned and the characters of Sam and Frodo are relatively androgynous. Furthermore, the hobbit resource cards include activities such as cooking and ‘hiding’ which could be viewed as subversions of a masculine identity. These embodiments can be contrasted with the depictions of the other ‘races’ within the game who all appear to embody identifiable hegemonic ‘male’ body shapes and features. For example, the race of ‘men’ (as aforementioned a problematic denotation of a race of people who do not all identify as ‘men’) are portrayed with rugged good looks and strong, square jawlines. Their hair, whilst long, reflects an image of perceived Anglo-Saxon normativity and they wear helmets and fighting gear to emphasize their prowess and presence in battle. Perhaps this raises interesting questions about depictions of masculinity and what masculinity might actually ‘mean’ in contemporary society as well as within the time period in which the novels were written? The hobbits are essentially the ones who save Middle-earth (even if my partner and I fail in our current endeavor) and they are not embodiments of the traditional hegemonic alpha-male.41 In contrast, the only three depicted female characters (Arwen, Galadriel and Éowyn) are all evidenced as white, thin and (to myself) startlingly pretty. As much as I do not wish to admit it, the first time I ever played this game in 2012, I wanted to be each of these gorgeous elves/women from a purely visual perspective (I had no idea as to their roles in the novel) and I still find myself drawn to collecting these cards (all three are resource cards which can be used on any activity track; the best type of card to gain during the game) to the detriment of my fellow gamer who may have been best placed to later use them. I am however now aware of their roles and find myself identifying with Éowyn as a fighter who subverts gender stereotyped roles and who finds herself slaying the ‘Lord of the Nazgul’ in the finishing scenes of the story. Éowyn in this regard acts oppositionally to the male figure who initially brings about the evil adrift in Middle-earth and perhaps even offers a reverse reading of the fall of ‘Paradise’ – Éowyn as Eve who saves Adam from his ultimate downfall which may or may not have been an intention of Tolkien, given his strong Christian beliefs.42 For these reasons I make an especial attempt to claim this card during the game (unfortunately I fail and my partner and I fall to the corruption of Sauron) but I feel happy that I subverted my male partner’s urging to forego Éowyn as this turning away would have sat wrong with me and my wishes at the current time, feeling in a particularly angsty feminist mood that afternoon. Luckily for me this is just a game and we can try and rid the world of evil again another time.

In playing through the game, aligning it with our own experiences and beliefs, we can also envision supplementary storylines differently; exposing the heteronormative relationships which contribute to the story such as the love interests between Aragorn and Arwen, Sam and Rosie, and Éowyn and Aragorn/Faramir. The game space allows us to create a dialogue about these relationships and to discuss the ways in which the fellowship encourages same-sex relations which can be viewed in multiple ways, both romantically and platonically, raising questions of how such depictions in culture are alluded to; defined in terms of camaraderie and ‘repair work’43 lest accusations of ‘lewdness’ be levelled by those fearing anything considered to be outside social ‘norms’. Such discussions highlight ongoing societal perceptions and issues which require addressing. In this instance moments of homophobia, racism and sexism can all be identified as potentially implicit in the game, whilst at the same time the ethos of the game would tend to counteract such accusations. This is a tricky terrain and yet by playing the game we raise questions around all of these issues and hope to raise awareness of the perniciousness of them within contemporary society.

Conclusion: Combating demoralization and keeping up the fight

Over the half-hour it took to play Lord of the Rings, I came to live in and (re)constitute myself in the space, reflecting on moments of disidentification, problems I had with parts of the narrative (both immediate and as a result of transtextual engagement with the game), and how I responded to these in certain ways. Whilst my partner became despondent that we lost I was at least buoyed and motivated by my attempt to insert myself into this space as a re-visioned, empowered female hobbit. We feel energized to try again.

Throughout the game, I re-visioned characters that better reflected myself and challenged aspects of the game’s patriarchal nature. As a ‘minority’ participant I felt I managed to resist and confound socially prescriptive patterns of identification44 by (re)investing the female characters (one of which I ‘created’ within the game space) with agency, building up richer narratives to surround them and making them more highly visible; aspects I found lacking in the game and Tolkien’s novels. Whilst the overall narrative of the game remained fairly linear (characters moved through prescribed landscapes in the order they appear in the novel/s) the various side-quest activity trails (Friendship, Travelling, Hiding) added an extra element of worldmaking to the game play experience. My re-visioned character, Rosie Cotton, chose to collect certain ‘life-tokens’ and special resource cards by focusing on the ‘Travelling’ activity in each landscape, allowing me to avoid the main ‘Fighting’ track which my partner took on. I made myself visible by both creating and aligning myself with Rosie Cotton, and also by physically moving along the ‘Travelling’ track whenever I could, rather than along the ‘Fighting’ track which might have allowed us to exit certain landscapes more quickly.

By both counter-identifying with the all-male fellowship and underlying patriarchal structures shaping Middle-earth and identifying with the goals of the adventure and my own desires to fight against oppressive regimes (i.e. patriarchy), I adopted a disidentificatory position in this space. I subverted the assumed character positions as denoted by the storyline, playfully taking control of an erstwhile minor female character invested by my own situated perspective to highlight the strong threads of female agency and survival I saw glimmering throughout the story; I led the way across Middle-earth to show who and what a female (hobbit) could be. The characters as embodied by myself and partner also communicated in a way I felt to reflect a commitment of working together, because of different abilities, highlighting resonances with the goals of intersectional feminism.45 For example, considering the game as a challenge to neoliberal values (such as patriarchy and imperialism i.e. Sauron – the all-seeing ‘Eye’) denotes a commitment to socialist work organized around collective benefits (gathering resources and destroying the ring to end oppressive forces against all) for a diverse group of people (differing Middle-earth ‘races’) who all contribute to success in various ways (via the special abilities of the playable characters).46 47 This ethos of working together across and within difference clearly arose during our game play encouraging us to comment on the power of such connections and the ways in which they link to feminist ways of doing and engaging in knowledge (re)production, with the potential to be explored by a wide gaming audience outside of delineated feminist knowledges. Whether such engagement is denoted as ‘feminist’ or not, the importance of highlighting such connections and the ways by which people adopt feminist practices in their everyday lives is surely worth exploring. For those who eschew feminism as being about ‘man-hating’,’ and/or a ‘lack of femininity’48 such play and concurrent discussions could open up feminist engagements to a wider population i.e. could the advantages of feminist knowledges be embraced through rethinking them through the lens of a game like Lord of the Rings? My gaming partner and I found it a challenging and compelling half-hour, infused with play and pleasure in its very entwinement of playing and thinking.

In sharing my experience and insights I invite further opinions and considerations of the game, evidencing a commitment to exploring the myriad ways by which knowledges are generated relating to differing life experiences. Similar analyses could be extended to other collaborative and/or transtextual games such as Shadows Over Camelot,49 Pandemic,50 and Arkham Horror: Third Edition51 all of which would offer rich sources of analysis were I not limited by time and space. Additionally, as mentioned earlier, adopting a wider analytical and experiential lens focusing less on strategic essentialisms such as gender52 and more deeply on intersectionality (the experiences and subjectivities of multiple players, the designers, the game content) may further encourage critical game play, thought and design inviting people to work and play cooperatively across divisions and differential positionings.53 There are many interpretations of this game out there and this is just one.

—

Featured Image is Rakotzbrücke by Dirk Förster, Public domain.

—

Pilar Girvan I am a UK-based PhD researcher interested in representation and knowledge (re)production both within and around the spaces of tabletop games. I previously completed a Masters in Gender Studies at Linköping University, Sweden, where I focused on intersectional explorations of sub-cultural spaces (mainly board games and video games), as well figurations of the feminist killjoy. I am an avid lover of board games (with a penchant for critique) and enjoy anecdotally sharing my board game play as part of the board gaming community on Instagram as @quirkyboardgamer.