The board game industry is currently experiencing an enduring renaissance, with sales, media coverage, and levels of creativity soaring. Indeed, in 2016 the industry saw a 28 percent sales increase in the United States, with global sales reaching over $9.6 billion,1 whilst current predictions point toward a market value of [$26.91] billion by 2025.2 Positioned within the larger industrial contexts of gaming, tabletop games “made six times more money than video games in the first half of 2016”3 through the online crowd-funding website Kickstarter, and ten times more in 2020.4 In fact, funding totals for Kickstarter’s tabletop games category demonstrate seven consecutive years of growth, with 2021 reaching a record breaking $272 million; a 13% increase from 2020.5 Over 30,000 games, both digital and tabletop, have now been funded via Kickstarter, with 2020’s board game Frosthaven topping the most funded list at just under $13 million.6 Instances of intertextuality and transmediality are also apparent in this renaissance when considering the success of projects such as The Witcher: Old World and Dark Souls: The Board Game, both ludic interpretations of popular video game worlds, as well as games residing within the cinematic universes of Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Marvel and Alien. From this renaissance—particularly in regard to games stemming from intellectual properties—an increasingly visible and active fan culture has emerged, one which offers vast insights into the nature of contemporary media fandom and the workings of the gaming industry as a whole. As such, I propose that by analyzing instances of transmedia storytelling, participatory cultures, and convergence, this emergent fan culture will reveal itself to be a considerably appropriate source of information for academics within the field of media to draw from when applying and exploring pre-established theoretical views.

Of particular interest to this investigation is the nature in which board games inherently promote notions of interactivity and play, more so than examples present in other media industries and even the video game industry. As Paul Booth notes, “using board games to analyze media illustrates the performative aspects of media interpretation and reveals the multiple ways all viewers play with their media.”7 Such notions of play can be analyzed and ultimately positioned within fan cultures and the industry as a whole, demonstrating how certain ways of interacting with media can have larger impacts on social, cultural, and economic contexts.

Using the Star Wars transmedia landscape as a focus for theoretical readings is an ideal entrance point for exploring the validity of board game fandoms for scholarly attention. Not only does it ensure accessibility on account of it being an extremely popular source text, but it simultaneously provides broad access to a particularly active fandom. This active fandom—within the context of the board game industry—is exemplified by the wealth of resources evidencing textual productivity in the form of fan-made expansions and rules modifications. Consequently, these will act as explicit evidence of the board game industry’s penchant for producing academically relevant communities, rich with both licensed and unlicensed sources. Despite the inherent physicality of board games, theoretical perspectives will largely be applied to evidence sourced through internet communities thus implying the application of methodological aspects of virtual ethnography.

Background and Explorations

The work of late media scholar and critic John Fiske serve as a useful entrance point to further explorations into concepts of the active audience and participatory cultures, particularly his explorations into “categories of productivity.” Whilst not commonly applied within academia to such ludic, analogue iterations of fandom, Fiske’s categories nonetheless demonstrate an insightful compatibility. Fiske identifies three forms of productivity apparent within media fandom: semiotic, enunciative, and textual. Whilst the construction of personal meaning from particular texts can apply to the consumption of contemporary board games, Fiske argues that notions of semiotic productivity are largely universal and “characteristic of popular culture as a whole.”8 With that said, it is Fiske’s remaining identifiers of fan productivity which display the most valuable correlations when applied to analysis of board game media fandom.

Enunciative productivity is the result of the personal aspects of semiotic productivity becoming more vocal, and thus ultimately circulated within a particular subculture. Identifying “fan talk” as the “generation and circulation of certain meanings of the object of fandom within local community,”9 Fiske then notes that “much of the pleasure of fandom lies in the fan talk it produces.”10 In the context of the board game industry, such fan talk largely occurs within online communities. Whilst this displays a deviation from the immediate social locality Fiske attributes to the generation of enunciative productivity, Suzanne Scott, assistant professor of media studies at the University of Texas, argues that when observing the increasingly digital performances of contemporary fan culture “we must amend Fiske’s description of the ‘restricted’ circulation of analog fan talk to incorporate the online forum/message board.”11 The fan mediated online resource boardgamegeek.com holds a wealth of information regarding board games and gaming culture. Aside from providing a vast board game encyclopedia, the site offers a space for fans to discuss their experiences and opinions, trade, and share their knowledge.

Such community forums undoubtedly achieve the circulation of meanings that Fiske attributes to enunciative productivity, yet some academics have criticized Scott’s relocation of the term to an online setting. Matt Hills, a lecturer of media and cultural studies at Cardiff University, argues that by “shifting from a ‘restricted’ to a distributed, mediated context…online postings, reviews or commentaries themselves become textual in the sense of being digitally reproduced and reproducible.”12 Such sentiments consequently position the online practices of fan talk as representative of Fiske’s third form of productivity, that of textual productivity. Textual productivity under Fiske’s definition, infers the unlicensed production and circulation of texts inspired by a licensed primary text, usually “narrowcast” and non-profit. Whilst it is certainly worthwhile positioning online “fan talk” as inherently textual, it is nonetheless important to acknowledge the potentially malleable nature of such categories in the context of a hobby where fans interact and enunciate explicitly in both on and offline contexts.

Deemed by prolific media scholar Henry Jenkins as “textual poaching,” Fiske’s definition of textual productivity has provided the self-professed “Aca/fan” with the basis for much of his studies on fandom, albeit focusing on more than the circulation of fan talk. The work of Jenkins helps to identify fans as extraordinarily active in comparison to other media audiences, noting their refusal “to simply accept what they are given, but rather insist on the right to become full participants.”13 In their efforts to achieve such participation, Jenkins identifies the internet as a “powerful new distribution channel for amateur cultural production,”14 offering a means of participation “that includes many unauthorized and unanticipated ways of relating to media content.”15 The aforementioned boardgamegeek.com is a notable exemplar of the distribution channels available to contemporary board game fans, offering a platform for budding fan/designers to share alterations to rules, additional game components, or even whole new game “poached” from existing designs and applied to certain franchises. Jenkins’s book Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture examines the nature of fans and their means of media participation, analyzing cases of textual production and the resulting cultural productions such as fan-fiction and fan-videos. With fandom possessing elements of cultural production, fans can be seen as re-appropriating source texts to cater to the “special interests of the fan community,”16 in turn negating the “self-interested motivations of mainstream cultural production”17 through “systems of distribution that reject profit and broaden access to its creative works.”18 The freely available print-and-play game Aliens: This Time It’s War demonstrates Jenkins’s ideas of textual poaching with its design sharing elements of popular card game Magic: The Gathering meanwhile applying a theme more attuned to this active fan’s preferences. The existence on the page’s forum of fan-made Gears of War and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles re-themes of this fan-made game serves to further illustrate Jenkins’s notions of poaching and the active fan audience.19

Introducing a contrast between the video game industry and the board game industry, Will Emigh, a video and board game designer at Studio Cypher and lecturer in game design, notes how the former can sustain efficient means of distribution through the utilization of online spaces. The latter, as producers of a more inherently physical product leads Emigh to suggest that “it can be difficult for authors to express their message without significant costs.”20 Combating this and exemplifying the participatory notions explored by Jenkins is the emergence of crowdfunding sources. Websites such as Kickstarter allow for designers to submit ideas for potential games and other products offering any potential fans the opportunity to help fund their ultimate production. Such fans, known as “backers,” will receive updates on the product’s progress, oftentimes contributing to elements of design, and eventually a copy of the product. When audiences are contributing to the development and production of media texts to such large extents, Jenkins’s notions of convergence as “both a top-down corporate-driven process and a bottom-up consumer-driven process”21 must be recognized. These convergent models of distribution “have allowed board games the leeway to tackle critical themes that the major publishing industries preclude,”22 securing designers, often through the input of fans or as fans themselves, the space to “address social issues more honestly and openly.”23 Such facets of the board game industry help to position this form of media as possessive of strong bonds between producers and consumers, facilitating the emergence of a participatory role for fans, which can aid in the production of culturally transgressive games and enhanced fan immersion within particular franchises.

Board Games as Paratexts

Providing the link between the board game industry and larger industries surrounding intellectual properties such as Star Wars, the work of Paul Booth, a media scholar and writer of several books exploring media theories through a tabletop gaming lens, is essential for expanding upon ideas of paratexts and their effects upon industry and fan practices. Booth defines a paratext as “a text that is separated from a related text but informs our understanding of that text,”24 noting that in the context of board games, meaning is created through “the tension between authorial presence and audience play: this meaning is created between player, designer and original text.”25 Thus a board game such as Star Wars: Imperial Assault can be deemed a paratext reliant upon “play” existing “within an already-extant space as well as within an imaginative space of the player’s own creation.”26

Adding to Jenkins’s understanding of convergence previously addressed in regard to notions of crowdfunding, Booth notes that “board games deepen and extend our understanding of cross-media convergence by relying on the complex interaction between the original text’s top-down ‘authority’ and the game’s bottom-up ‘play.’”27 Booth’s identification of “play” as a “specific mechanism by which players inhabit and make media their own”28 also serves as a useful starting point in the application of board games to the theories on “play” discussed by senior lecturer in transmedia and digital cultures Colin Harvey.

Analysis of board games can offer insight into the unique contemporary form of transmedia storytelling that the industry and its creative community conjure. Whilst recent study into transmedia storytelling has largely emphasized the effects of digital and online spaces, the analysis herein demonstrates the board game industry’s proficiency at combining both the physicality of games and the act of play itself, with the communities and creative avenues afforded to the internet.

The board game industry arguably harks back to a time where opportunities for transmedia storytelling existed in a largely physical space. Harvey reminisces on his transmedia escapades during the 70s and 80s where “‘storyworlds’ unfurled across films, novels, comic books, pen-and-paper games”29 and the act of playing with licensed toys. Harvey comments on the centrality of “play” to the transmedia storytelling experience, elaborating that “‘creative play’ is vital to the process of making stories.”30 Indeed, this centrality is maintained within the context of the board game industry, often with “play” evolving from the mechanical constraints and rules of a particular game, to the “play” associated with textual productivity. Harvey suggests that “in terms of the creation of transmedia storyworlds, the experimentation associated with playfulness might give rise to new characters, settings, scenarios or plots.”31 Whilst such suggestions have been widely applied to transmedial examples of fan-fiction, comics, and fan videos, their analysis within the board game industry, and in particular fan made game texts, is arguably lacking. Thus, in the following analysis of a pair of fan-made expansions to popular licensed games, Harvey’s broad approach to transmedia storytelling is supported whilst offering a potentially valuable but underused form of media applicable for future research into the relationships between industries and fans.

Star Wars as Paratext

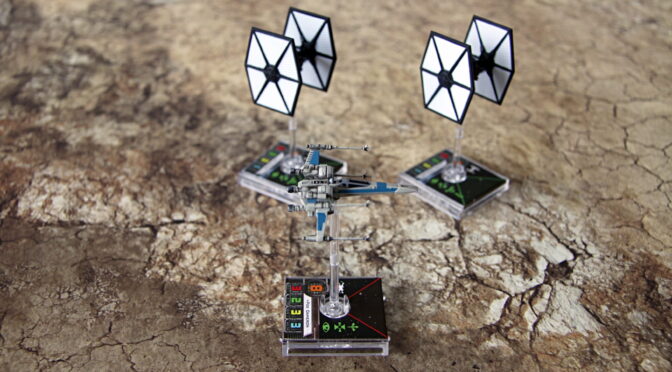

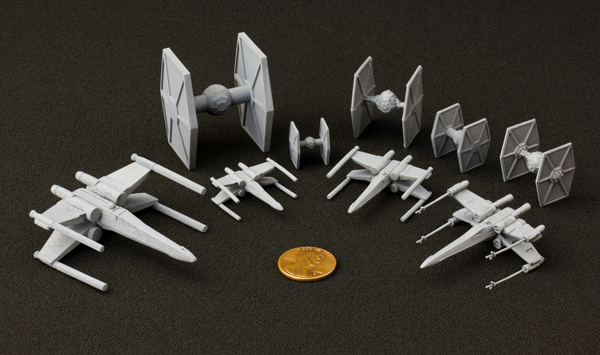

The gameplay of Star Wars X-Wing: The Miniatures Game revolves around players manipulating detailed miniatures depicting the franchise’s various ships around a designated play area. Particular movement templates are chosen in secret and then performed, with players then ideally maneuvering their ships into positions suitable for attacking the opponent. Such games are indicative of possessing what Kurt Lancaster describes as a haptic-panoptic relationship between fan-players and the images on physical pieces and the cards, often depicting particular pilots or key scenes from the films, yet rendered through detailed illustrations. Such a haptic relationship relies on players’ abilities to touch, experience, and reconfigure an element of the franchise “they have only previously viewed from a distance,”32 usually through the screen. The haptic nature of paratextual games essentially freezes previously dynamic visual moments, allowing players to interact with their fandoms with more agency, yet under the governance of game rules. The panoptic element of the game refers to how over time, the cards played and miniatures positioned represent a distilled tableau of the franchise, “a panoptic representation of the universe, to be looked at in one sweeping view.”33 Of course, considering the variety of paratextual games within the industry, some perform better, or at least differently compared to others, at providing fan engagement through haptic-panoptic elements.

Arguably, these notions of haptic-panoptic performances apply more fittingly to the structure of play Star Wars: Imperial Assault. Fantasy Flight’s popular miniatures game effectively acts as a Star Wars themed “dungeon crawl,” a genre of game that distills the experience of popular roleplaying games such as Dungeons and Dragons, offering players a shorter, more structured approach to game mechanics of exploration, combat, and character development. These games, Imperial Assault included, are played out across modular map tiles, with players unlocking larger areas the further they explore. Through the combination of narrative, card-play, dice rolling, and miniatures, Imperial Assault offers a literal panoptic aerial view of a Star Wars story. Card events and character boards are complimented by detailed miniatures atop familiar set pieces, with the board’s final state undeniably suggesting an active, haptic engagement with the franchise.

Fitting into Harvey’s analysis of Star Wars toys and video games, board games also “rely on the operation of memory,”34 and in particular, notions of “nostalgia play.” It can be summated that the tactility of board games and toys tap into a nostalgic relationship occurring between childhood experiences with certain franchises, and the paratextual transmedia storytelling associated with tactile play. In part referencing the physical special effects of the early films, Harvey notes, “Star Wars is, at some fundamental level, a tactile franchise which must look and sound real. This cultural memory could represent the enduring legacy of the toys—the transmedial paratexts—that constituted young fans’ experience of the franchise in its earliest days, and the memories associated with them.”35 Thus, the games Star Wars: Imperial Assault and the Star Wars X-Wing Miniatures Game can be seen as the board game industry’s continuation of a tactile sense of nostalgia, increasingly lost within the franchise’s contemporary, more digital form, encouraging fans to “play” and continue in the formulation of the storyworld. Harvey accentuates the importance of this tactile transmediality, noting that in some instances, namely the influence of the 1980 Boba Fett toy on his continuing mythos, they may “feed back into the ongoing narrative of the transmedia franchise in question.”36 Whilst this is not explicitly apparent within the Star Wars board games and their relation to canon, the production of fan made campaigns nonetheless provide an expansion to fan players’ interpretations of the franchise.

Blurring the Line Between Consumer and Producer

Despite these licensed game iterations largely satisfying elements of fandom usually sought through unlicensed means, fans within the board game industry have nonetheless used such games as starting points for even deeper involvement with franchises. Indicative of enunciative productivity, fans can be seen discussing the objects of their fandom through online forums, and to a lesser extent, organized play events promoted within the industry. These spaces of fan talk have consequently led to textual productivity, with fans discussing their wishes for particular games, be they for personal, affective means or for the expansion of storyworlds, and physically realizing them. Thus, the following analyses focuses on the notions of transmedia storytelling and affective play that can arise from Jenkins’s views on textual poaching.

In addition to the board game industry’s catering to notions of nostalgia play and the resulting contributions to a franchise’s storyworld through transmedia storytelling, other theories on play indicate a more explicit engagement with the personal and social contexts surrounding the industry itself. Referencing Hills’s notion of “affective play,” whereby fans’ application of their own emotional attachments to media texts results in a form of cultural creativity which deviates from usual media experiences, Booth notes how media producers may sometimes even entice such engagement.37 The board game industry is certainly indicative of this, both in the context of major publishers, but perhaps more so, the active fan audience. Whilst large game publishers such as Fantasy Flight do entice audiences to “play” within particular franchises, it is the creative efforts of fans and the ensuing textual poaching associated with unlicensed expansions and game alterations that most explicitly exemplify notions of affective play.

In the process of straying from both the game’s and the films’ predetermined structure and content, players of custom campaigns and other examples utilizing additional fan text, construct a more personal narrative and “paratextual world that extends beyond the boundaries that were established by the original text.”38 Hills notes that the varying types of “play” associated with the practice of fandom are “not always caught up in a pre-established ‘boundedness’ or set of cultural boundaries, but may instead imaginatively create its own set of boundaries,”39 thus allowing for active participants to explore personal and cultural issues. Contrasting with the video game industry, which has often been subjected to various critiques, the board game industry and its wealth of designers and communities have recently demonstrated the potential for progressive approaches towards particular social and cultural issues. Lundgren and Bjork repeat accusations that suggest the use of video games may “increase aggressive behavior, promote sedentary lives, increase the risk of obesity, portray sexist worldviews, and that they show simplified and shallow versions of reality.”40 In relation to the mention of sexism, the board game industry has historically been perceived as being largely male-oriented space, but an increasingly vocal female community combined with the board game’s physical nature being prone to liberating examples of textual productivity, the landscape is beginning to change.

Star Wars: Imperial Assault is a prime example demonstrating “affective play” and how the board game medium and the connectivity of online fans has enabled female players to increase their agency in regard to the micro elements of actual game play and transmedia storytelling, and the macro elements of erasing the gender divide in the larger gaming community. Boardgamegeek.com’s file section allows for the uploading of fan-made content, which in the case of Imperial Assault, has often been the choice of alternative playable characters to those offered as standard. Thus a multitude of various identities become available for players to utilize in order to maximize their immersion within the game, whilst simultaneously demonstrating how the textual productivity board gaming affords surpasses the often restrictive options for identity formation and visibility in video game texts.

Boardgamegeek.com user “Darth Jawa” and his fan made campaign for Imperial Assault exemplifies the aforementioned notions of affective play, textual productivity, and transmedia storytelling. His custom made campaign For a Few Credits More,41 complete with printable terrain maps, character sheets, and additional cards and tokens, enables fans of both the game and films to play the role of bounty hunters—as opposed to the standard rebel characters—hunting down a mysterious rebel leader. This reversal of alliances both appeases fans of the game that may wish to inject some variety into their games and expand upon official content, but also fans of the Star Wars franchise in general. The campaign’s focus on bounty hunters and their encounters with varying races (namely the Twi’lek) highlights Jenkins’s summations that fan audiences will “work to resolve gaps, to explore excess details and undeveloped potentials,”42 which in this context involves the active production or alteration of a game-based transmedia narrative to explore and expand upon existing, yet perhaps sparse elements within the Star Wars canon.

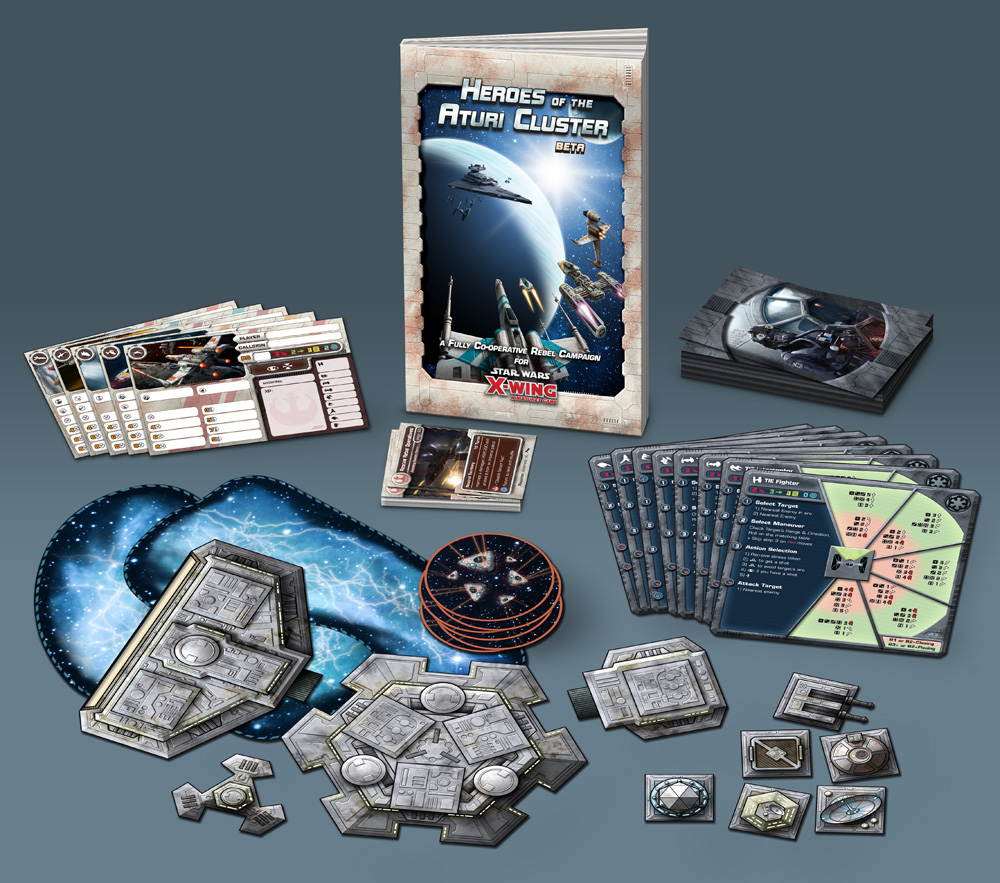

Heroes of the Arturi Cluster is a fan-made campaign for the X-Wing Miniatures Game that, through the co-opting of the original game’s player versus player format, demonstrates how textual productivity can alter games at a mechanical level to suit how players want to play. Heroes of the Arturi Cluster significantly alters the game’s structure, replacing the traditional Imperial player with a game controlled AI mechanism. This in turn renders the game as a cooperative, communal experience requiring players to efficiently work together, and as the campaign book suggests, even role-play their characters. This alteration to game mechanics could be indicative of the fan-designer’s “poaching” of the increasingly popular cooperative mechanic within the board game industry—a genre made popular following the success of designer Reiner Knizia’s award winning paratextual board game The Lord of the Rings in 2000. Additionally, it could also be seen as providing a thematic link to the camaraderie depicted within the Star Wars films.

The fan expansion is clearly celebratory of both its cinematic and board game sources, with the well constructed fan website featuring a high quality downloadable campaign booklet, printable terrain pieces and cards.43 The campaign book itself features several images from the Star Wars transmedia landscape including the films, comics, fan art, and the original X-Wing game, as well as suggesting an accompanying Star Wars soundtrack during play. In the campaign book’s foreword the designer states: “Since X-Wing miniatures was released in 2012 there have been numerous fan made campaigns, ideas for new terrain types, and projects to write artificial intelligence to control opposing ships. To my knowledge, no one has combined these elements into a cohesive package.”44 This statement is representative of the nomadic fan, who in this case is not only borrowing from licensed sources but also from within the fan community itself, a notion previously explored in the review of Jenkins’ work on textual poaching.

Participatory Possibilities

This study into the board game industry has highlighted emerging academic voices within media and fan studies alongside confirming the viability for pre-established theoretical views on media to be applied to this exciting and dynamically progressive medium. The various forms of “play” attributed to consumer interactions with media have been soundly identified within the licensed, mass marketed texts available to audiences, suggesting that media industries themselves are adopting and encouraging active fan practices. Alongside the financial benefits of catering to fan activities previously perceived as “fringe or underground,”45 the board game industry can also be seen as a component in the continuing expansion of franchises through transmedia storytelling. Yet, most interestingly, it is the more explicitly participatory and unlicensed practices of board game fandom that yields the most valuable information regarding theories on textual productivity, affective play, and transmedia storytelling. Or as Greg Loring-Albright writes, these games return “agency to the players, casting them as fan re-writers in the tradition of fan studies. By mixing and matching game elements from different diegetic time periods…or levels of canonicity…these empowered players use the game’s system to create narratives that the hegemonic owner of the franchise has deemed inappropriate.”46 The creativity exemplified by fans’ productions of unlicensed expansions, has, in this short analysis, demonstrated the potential for the board game industry and its community to progressively engage with personal, social, and cultural issues. This has been achieved through the adaptability of characters and scenarios, and through the malleable avenues of production and distribution that bypass official methods, ultimately complimenting fan discourses on issues such as gender, sexuality, and race.

In summation, the paratextual board game industry affords academics a rich tableau of sources to expand upon the fields of media studies and fan studies, with those wishing to delve beyond the official and licensed contexts of the industry potentially being rewarded with information concerning some of the most explicit examples of fan textual productivity within the media industries. Furthermore, with the current surging popularity of board games, the industry will undoubtedly provide an increasing number of viable case studies to compliment prior research. Indeed, the boardgamegeek.com file section for Dark Souls: The Board Game has already demonstrated the eager participatory nature of fans, evidenced through the uploading of custom map tiles,47 boss encounter cards and even 3D printed miniatures,48 merely days after the game’s release. Such an example, demonstrating familiarity with creative technologies, draws forth a potential avenue of investigation in regard to the levels of technical proficiency, bordering on professional, fans may possess and expend in the pursuits of their fandoms. Thus further analyses into the board game industry may benefit from broader ethnographic considerations on consumers’ technology-related human capital, alongside their cultural and economic capital.

–

Featured image from Piqsels: https://www.piqsels.com/en/public-domain-photo-fyfvm#google_vignette. Public Domain.

–

Chad Wilkinson is a freelance writer from the south coast of England. Since receiving his Masters degree in Media and Communication at the University of Portsmouth, he has contributed work to several publications. Currently, he is a reviewer and features writer at Tabletop Gaming Magazine. Primarily, he is known for “Around the World in 80 Plays,” a regular column examining the tabletop hobby from the viewpoint of a different country each month.