This essay narrows the gap between analog1 and digital games by connecting Dungeons and Dragons (1974) or D&D to the origins of the video game industry. Despite its analog status, D&D is a video gaming platform much like a Nintendo Switch, Mattel Intellivision, or the Atari Lynx. In fact, it is the first platform, or environment that programming can be performed on2. D&D was formed of the same military logic as programming languages and shared a release date with the first computers available for public use.3

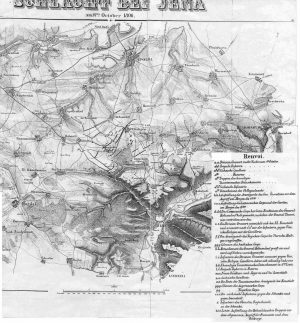

The concept used to bind these histories together is a long, discontinuous, yet disconnected process Gilbert Simondon refers to as individuation.4 This process is a de-segregating one that allows the researcher to make sense of disparate events and objects over time. Starting with the military campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte, D&D manifested through a collection of intersections between war games, commercial play, and the growth of computation. This role-playing game offered these new programming enthusiasts a glimpse at what logic-based games could be besides sport, toy, and physics-based games.

Scholarship on D&D

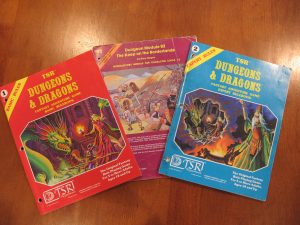

It is no controversy to say that D&D is the first role-playing game (RPG).5 RPGs are game systems through which players assume the role of a character in fantasy world. The player-character relationship is mediated by easily modified rules, variables, descriptive objects, and randomization. As the first of these types of games, D&D quickly spread around the world and remains one of the most popular games of all time. Now over 45 years old, D&D can still be seen everywhere in nearly every language on the planet. The addition of streamed sessions, online, and celebrity-played games have broadened and diversified D&D’s audience in the present. Yet, scholarly work on D&D often does not reflect its cultural and historical complexity.

For example, one aspect of D&D is that as a piece of white male geek culture in the United States, it has appropriated other cultures. The history of the Oriental Adventures handbook for D&D allows us to glimpse at how little white male culture has changed.6 The history of D&D also contains a lack of representation of a diverse gender representation,7 LGBQT+, or handicapped or other-abled individuals.8 What’s more, much of this representation from the game’s initial creation has continued mostly unabated. The discussion of D&D currently sits within a space that could be better described as a culture war9 that transcends medium.10

As narratives about specific fights in the culture war, each of these pieces are very important. They allow us to see something about ourselves in the present. However, each piece gets lost among an undefined, opaque, and often undiscussed historical context. As a result, most work about D&D is not connected to anything more than this nebulous object called D&D. This is a consistent issue with the state of game studies as a whole (analog or otherwise). We have forgotten to incorporate gaming’s history in our analyses and so offer little more than temporally constrained observations rather than poignant moments of criticism. By reconnecting D&D to its history, each of the above pieces and all other pieces attached to D&D can move beyond analog game studies toward the study of how playful culture is–or the play element of culture11 Some even argue that objectivity as we understand it now was also created during this time.12 The present research traces the birth of the platform through the success of Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaigns in Prussia, calculating probability and chance of actions, and the training of military officers in the logic of war through war game.13 The logic of war was perfected as chance and evaluation became the focal point of increasingly complicated statistical measures. This process would inevitably give rise to computation itself.14

But logic, most easily represented in pop culture through Star Trek’s Spock, is often missing the narrative, emotion, and the minutiae of humanity. Those human elements of war, the “narrative” of soldiers within those wars began to rise in popularity in the post-World War II world. That narrative would join with the logic of war in 1974 when a small group of game developers happened upon an innovation: players could use the logic of war to give weight to soldiers inside a narrative that they all shared. It was called Dungeons and Dragons (D&D). Almost immediately after its creation, a significant portion of modern gaming was built using the relationship D&D fostered between narrative and logic.

Platform Studies

In order to explore the D&D’s individuation as the platform, it is important to define a few terms. Additionally, it is important to describe the processes through which those definitions came to be as it is within these processes through which individuation occurs. The most important of these definitions is what exactly a platform is. The Platform Studies series has defined the platform as an environment that programming can be performed on15 and Nathan Altice has advanced the argument that analog games like playing cards can be viewed as a platform.16 The present research contributes to this discussion by linking analog games to the individuation of–or process of becoming a named technical object.17 The process of individuation begins well before the computer appears.

It is not enough to simply state, “D&D was the first platform” as this is a dubious, if not destructive statement. The platform studies space revolves around physical objects like the Atari 2600,18 the Nintendo Entertainment System,19 or environments like Flash.20 None of these are games in their own right, so how can we call a game like D&D a platform? What’s more is that this definition is just as easily broken by calling upon the materiality of computation and its requisite electrical currents, silicon, and machined language. In order to make a better case, this essay begins considering how platform is defined.

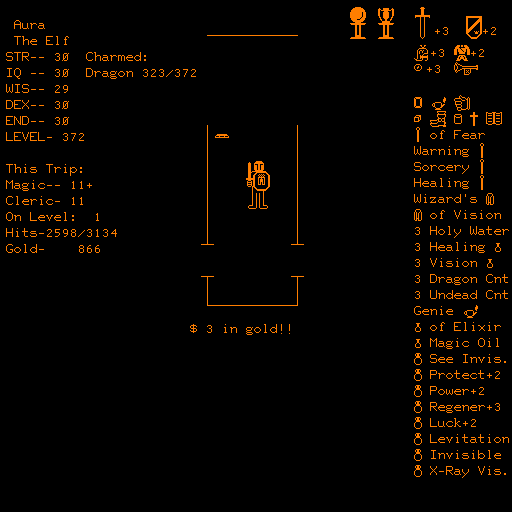

According to Montfort and Bogost, platforms are, “Whatever the programmer takes for granted when developing, and whatever, from another side, the user is required to have working in order to use particular software, is the platform.”21 Using this definition, the first step in determining if an object is a platform is to find what the programmer takes for granted and what the user needs to have working. This essay takes this formula literally—I argue that D&D’s system is its programming language, the GM is it’s processor, and the players and GM together work as its memory.

Thinking through the stated definition then, one can say that users of D&D must have working knowledge of The Player’s Handbook. This is what the programmer or GM takes for granted. This is also what every video game requires, the player’s understanding of their side of things. The GM then is required to have developed a space for playing using the other two core books: the Dungeon Master’s Guide and the Monster Manual. The objects that embody the user are the same as a video game, their avatars or characters – one of the most important developments from D&D.

Finally, what exactly is the software that D&D runs? The campaign—or connected game sessions—are what we would refer to as software running on a platform. This is the assertion that this essay explores. The most direct way to contextualize this point is to consider the connection between D&D and the history and philosophies surrounding war games.22 To understand this connection, one must first understand Napoleon Bonaparte’s influence on the world.23

War and play are inexorably linked through the computer and D&D borrows from this legacy. The link is best captured through the campaigns and tools of Napoleon Bonaparte. According to Hegel, Napoleon embodied the spirit of the age he lived in and that spirit was mathematics, probability, and complexity.24 The spirit of the age surrounded careful measurements and use of data in an effort to maintain a war machine that was magnitudes of complexity beyond anything anyone had seen up until that point.

Understand that the concept of war had shifted throughout the 1700s to battles that occur in large open land. Because of this openness, spatial reasoning became essential and this opened the act of making war up to an increasingly complex machine. Napoleon’s use of the Carte de France – the most detailed map ever created up until that time – was how Napoleon not only embodied the spirit of the age, but changed the world forever.25

Therefore, the referee links this history of wargaming to a history of computation. The referee, or gamemaster, is a a system of computational logic that multiple users input commands into. This logic-engine is very similar to what we now know as the computer processor.

D&D as Platform Architecture

Fast forward to the 1960s, where the logic of computation is outsourced to a referee, a set of manuals, and a dodecahedral random number generator. With the publication of D&D, the role-playing game platform was born. D&D showed us how logic-mediated play could generate meaning for the players. At this time video games were based on physics (e.g. Tennis balls, bullets, and asteroids) or toys (hide and go seek, poker, and mazes). What the publication of D&D showed was that another form of play within logic was possible. The potential commercialization of this form of play was evident as computer-mediated games based on D&D were created immediately after its release..

As an object that united logic and narrative, the final evidence of D&D’s existence as a platform can be found in how it was translated to computation. This is important as it is an essential quality of any platform within which creators can port games from one platform to another. The historical appearance of D&D coincided with college students gaining access to the first computer systems available for enthusiast use. The first video game developers not making games based on toys or physics ported D&D’s pseudocode into these new computational spaces.

The act of individuation is often a long process that is not always obviously connected. D&D combined computational logic with the narrative of war. It did this by fostering an attachment to a character that lived in its own world with its own rules. In this way, players could explore war-based concepts while simultaneously experiencing a lessened, but non-zero amount of that character’s emotion.

The first video game developers not making games based on toys or physics ported D&D’s pseudocode into these new computational spaces. By quantifying character attributes, D&D had created an easy to translate language of pseudocode or set of logical structures that could be used in computer programs. D&D’s pseudocode spoke to the then trend of teaching programming through structures.26 Through this pseudocode, these new programmers could translate their experiences into the digital spaces of computation.

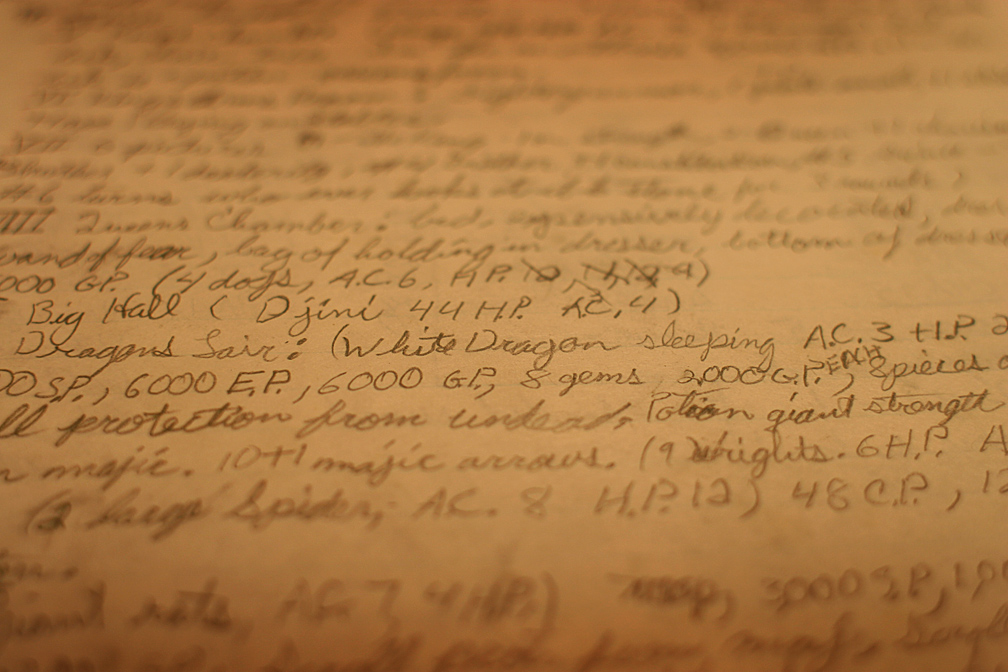

The game pedit5 (1975) was one of the earliest D&D inspired games. It appeared not too far from the first Gencon that D&D was available for in Champaign-Urbana, home of the PLATO computer system. The creator of pedit5 Reginald “Rusty” Rutherford notes about his creation process that:

About the spring and summer of ’75, my friends in the gaming group at Illinois had gotten deeply involved in this [D&D]….It was a fierce game. It was awfully easy to die at level 1. Well, we kind of got really deep into it to the point where not much else was happening in our lives.27

The name pedit5 was not the name of the game itself but the name of the “lesson” file that the game existed on. Pedit was the Population and Energy Group and program slots 1 through 5 were the spaces of memory upon which that group could store programs. Rusty was a programmer for this group and stored his game inside the 5th memory slot. This game was a hit and featured numerous aspects of D&D. In his own words:

I used the basic features of D&D as much as possible: hit points, monster levels, experience and treasure awards, and so on; the character was a combined fighter / magic user / cleric; in a monster encounter, the character had a choice of fight (F), cast a spell (S) or run (R); after that, if the monster was not defeated or avoided, it was a fight to the finish run entirely by the computer.28

Unfortunately, this game was constantly deleted by PLATO administrators. Games were frowned upon due to the scarcity and expense of memory at the time. Inevitably, Rusty abandoned the game; however, the game had become so popular that others began to take the game’s code and “improve” it in some way. This led to a game that took or borrowed from the core of pedit5 but, “improved” upon it.

Rusty’s pedit5 began an intense period of competition and development. In doing so, D&D as a technical object was fully realized. In response to the inconsistent availability of pedit5, Gary Whisenhunt and Ray Wood created the game dnd (1975). These new programmers wanted to take the core of pedit5 and improve upon it. They focused on making the game “fun” more so than making the game a direct port of D&D. Whisenhunt and Wood were also administrators of the account that hosted their file. This meant that their game would not disappear or need to be uploaded elsewhere. Their file space was safe.29 dnd was unique for a number of different reasons.

First, Whisenhunt and Wood decreased the difficulty of pedit5 by making it more survivable. Next, they added a maze editor so that they (and others) could create dungeons for players to run around in. Third, they added consequences to actions. For example, players’ avatars grew tired if they carried around everything they found. Finally, dnd did something no other game had done up until that moment; it included a “boss” monster for players to defeat at the bottom of the dungeon. These big monsters would be the final hurdle for players to overcome in order to win. The creation of dnd started a process within which new programmers would identify new ways to change or improve an existing game based on D&D with new concepts and new ways to excite players.30

dnd signaled the start of what could be referred to as the curve of constant improvement. When Rutherford created pedit5, he used his best guess at how to use the computer to replicate his experiences inside of D&D. After this, for a variety of reasons between a dialectic of experience with D&D and programming knowledge, a variety of new games appeared. While this strand is tied to the groups that had access to PLATO, the process itself was replicated in a variety of ways with similar results. The most famous of these other strands are the games inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure (1977).31

Between pedit5, dnd, and Adventure, the foundation of modern video gaming was set. These early games formed the boundaries within which games would develop. The set of video games that build on these initial D&D inspired games would further define this type of play within computation. Games like Oubliette (1977), Akalabeth (1979), and Castle Wolfenstein (1981) expanded upon the boundaries of the earlier games as D&D itself began to cope with its own weight. Out of the third generation come genre-defining global phenomena like Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord (1981) game and the first-person shooter, Wolfenstein 3D (1992). From this base, games steeped in the way that D&D (1974) organized rules and narrative became a global industry.32

Conclusion

When war games were created, the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz criticized them for focusing only on the disconnected logic of war. The narrative part of war, he claimed, would be kept in texts written by soldiers from their perspectives on the battlefield.33 Between the early 1800s and late 1960s, narratives, philosophy, mathematics, militarism, and systemic thinking all individuated a space that would overcome Clausewitz’s criticism. That technical object that was born after the process of individuation was called Dungeons and Dragons.

In this game, players construct a character to exist inside of a world that contained its own ways of knowing and doing. Role-playing games allowed players to form relationships with foreign characters in worlds with systems that could or could not exist in the real world. Players engaged in play with software, a campaign or connected series of adventures, that was built using the platform of Dungeons and Dragons.

The emotional and narrative quality of these sessions were not only shaped by the rules at the table, but co-created by the game master, the players, and the procedurality of the game system. The resulting exploratory aspects of this game were directly connected to war and as a result, shared an ancestor with the history of computation. Seeing easy to translate concepts like hit points, attributes, and formulas for damage, programmers replicated the complex logical relationship inside the computer. These attempts helped to move video gaming away from physics-based or toy-based concepts and toward ones that D&D itself helped to create.

While D&D was the individual or technical object that was produced in 1974, it was not static. By the mid-1980s, early pioneers who sought to replicate or translate their D&D campaign’s pseudocode to the computer established new genres, new foundations upon which to build. This shifted the space of the platform, the space of D&D. With every new edition, D&D shows us what the potential for the strictly computational platform is and where we it has yet to go.

–

Featured image is “IMG_7857” by Marc Majcher @Flickr CC BY-SA.

–

Nicolas LaLone, Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor at University of Nebraska at Omaha. His research focuses on the ways that computer technology and culture interact within disaster and emergency response. He uses the study of games as a means to find new ways to increase coordination and collaboration within response efforts. In his spare time, Nick is a collector of old war games, board games, and histories of the social sciences from the early 1900s.