Darth Vader’s signature TIE fighter swoops in behind Luke Skywalker to line up the killing blow when, at the last second, the villain’s ship is disabled by laser blasts from the Millennium Falcon, piloted of course, by… Rey and Finn? Where were Han Solo and Chewbacca?

This sort of situation plays out regularly in Fantasy Flight Games’ Star Wars X-Wing Miniatures Game (2012).1An expandable miniatures combat system moreso than a board game, X-Wing (as I’ll refer to it to save space) allows players to mix and match Star Wars heroes and villains on the table via plastic models of iconic, recognizable spaceships.

In this piece, I will undertake a close reading of X-Wing and surrounding texts in an attempt to locate the player within the game. While players will sometimes refer to themselves “pilots,” the game suggests a different role: Namely, that players of X-Wing are placed into the combined role of filmmakers and audiences. The game’s dedication to the scaled accuracy and detailing of its miniature spaceship models, coupled with its use of secret movement (which, if players are playing well, results in moves that surprise and delight their opponents in the way that a dramatic movie would), point to a non-diegetic position for the player. Instead of placing its players into the diegetic Star Wars universe, X-Wing places its players onto an imaginary Lucasfilm / Industrial Light & Magic backlot, playing with plastic spaceship models just as the creators of the original films did. While players of X-Wing do not generally conceptualize themselves in this way, using this model of player positionality opens up new possibilities for reading X-Wing.

Having so positioned players, this reading will then pivot to X-Wing‘s unique take on Star Wars canon: The game’s product line includes ships and characters from sources that are currently canonical (i.e., the original films, the contemporary Star Wars Rebels cartoon) and ships that were previously considered canon but have since been relegated to non-canonical status. This situation between canons returns agency to the players, casting them as fan re-writers in the tradition of fan studies. By mixing and matching game elements from different diegetic time periods (e.g. the example above) or levels of canonicity (e.g. a canon ship flying alongside a non-canon ship) these empowered players use the game’s system to create narratives that the hegemonic owner of the franchise has deemed inappropriate.

By shifting lenses, we can appreciate the strange and unpredictable outcomes of games as elements of a transmedia franchise. By giving the game’s structures agency in the first half of the piece, we can discover a unique take on player position (one that most players, in my experience, do not use when conceptualizing of their own play). This new positioning, however, results in a situation where the players are re-empowered to craft their own Star-Wars-but-not-quite-Star-Wars narratives, using the game’s systems as an engine for creative rewriting.

Blast It, Biggs, Where Are You?

One of the first documents that you encounter when you open X-Wing’s Core Set suggests that you should conceive of yourself as a pilot: “We wanted to give players the opportunity to pilot the iconic ships from the Star Wars universe.”2 While it is understandable that the position of the player in a game like X-Wing would be that of the pilot, a close look at the material and thematic constraints of the game do not allow for a coherent diegetic reading of the player as the pilot.

The first such constraint is point values: X-Wing uses this common wargaming convention to determine which ships’ players can field in a given session. Each pilot (there are multiple per ship) is given a point value, and a list of allowable upgrade cards that can be equipped to that ship, each of which is also given a point value. Players can field ships of their choosing, selecting from numerous options, as long as the sum of ships and upgrades does not exceed a set value (100 in the game’s most common format). In most games of X-Wing, playing a single ship is rare. The most expensive ships have a base cost in the forties, and even fully upgraded, rarely exceed sixty points. Thus, suggesting that a player is playing as a “pilot” in X-Wing is disingenuous, at least when referring to the game’s standard play mode.

To reach their full 100 points, almost all players field from two to eight ships, perhaps situating them as “squadron leaders” in the diegetic parlance of Star Wars. Even this position, however, is precluded by the realities of gameplay. If one is playing as a squadron leader, presumably one seats oneself in a ship within the playable squadron. In all three “original trilogy” Star Wars movies, we see squadron leaders in starships flying alongside their fellow pilots. So it would follow that, if the player is a squadron leader, they would have to choose a ship in which to seat their in-game representation. The game contains no such mechanic, however. There is not a “king” piece (to use a chess analogy) that corresponds to the player’s position as a squadron leader whose survival is necessary to win the game. No matter which or how many ships are destroyed by the opponent, as long as a player has a single ship in play, even a lowly “Rookie Pilot,” they have a chance at victory.

If the players of X-Wing are neither pilots nor squadron commanders, perhaps they are more distant command figures. Star Wars (1977) has a clear option for this position: Princess Leia and the Rebel commanders surrounding the green-and-black table in the war room during the cutaways in the climactic final scene. Since the game precludes situating players within the ships on the game table, perhaps players of X-Wing are meant to assume the roles of these characters. Nothing in the game’s promotional materials or physical artifacts suggest this, however. Pilot and upgrade cards feature art focused on ships, crew members, and mechanical elements.

If players were meant to situate themselves as Princess Leia or another Rebel commander, it seems safe to assume that the game would re-create or at least nod to the game-table-like war room prop, or the vertical screens in the control room. The lack of textual or visual referents to this (or other, similar scenes: Admiral Ackbar in his wheeled command chair; Emperor Palpatine watching his squadrons through the window of the second Death Star) indicates that the game does not situate its players in this part of the Star Wars universe either.

Where, then, is a player to sit? Not in the cockpit of a single fighter, either as a solo pilot or as a squadron commander. And not in the base or command ship launching scores of ships into a pitched battle. It seems that there is no diegetic position for the player of X-Wing to assume.

Industrial Light and Miniatures Game

Because this is a game centered on a (transmedia, but originating in) film franchise, it is no great leap to match the game’s diegesis to the film’s diegesis, and, by extension, the game’s extra-diegetic space to a filmic extra-diegetic space. In short, if players of X-Wing are not onscreen in a Star Wars film, maybe they’re off-screen. If the realities of standard gameplay in X-Wing forces players to take an off-screen role, then a separate line of inquiry points towards the player’s specific role behind the camera: That of the Industrial Light and Magic animators. The original trilogy of Star Wars movies (Star Wars, 1977; The Empire Strikes Back, 1980; Return of the Jedi, 1983) relied heavily on model-based special effects for its space sequences.

Fantasy Flight Games’ marketing materials highlight both the high quality of their pre-painted models, and their fidelity to the source text: “Accuracy was paramount to us, regarding … the fine details of the miniatures.” 3 This focus on the physicality of the models is important. After all, X-Wing can be played without the models; the game’s rules only require the plastic bases and the reference cardboard placed onto them. Calculating position, range, and adjacency can be done without the model ships (and, indeed, sometimes close positioning of large ships requires that the models be temporarily removed). In this light, the models may seem to be an afterthought, yet the centrality of these models to the marketing (and to many positive4and mixed5 reviews of the game) indicates that they are not to be overlooked. Indeed, as someone who has played X-Wing myself, I can attest to the joy of looking at a table covered with detailed models of Star Wars ships, and the comparative boredom of looking at the same table covered with plastic-and-cardboard squares representing those ships.

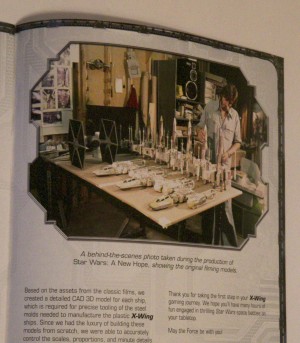

These two observations about X-Wing point us to the place where the game wishes to situate its players: By denying players an explicit position within the diegesis (as a space pilot, squad leader, commander, etc.) and by rooting the joys of its play in the specific physicality of its plastic models, X-Wing positions its players as filmmakers, specifically, as special-effects-makers. The previously-cited “Production Notes” section in the core game’s rulebook gives us more evidence of this: A photograph of an uncredited special-effects worker finalizing a model on a table covered with large Star Wars models. This man, the rules seem to suggest, is you: the purchaser of this product, the reader of these rules, and the player of this game.

Having used the lens of the game-as-text to situate its players, it is now time to turn the tables. X-Wing situates its players as filmmakers, so it is worth considering what kinds of films these filmmaker/players are making. Having given agency to the game system, it is now time to place agency in the hands of the players, these miniature-George-Lucases.

Remix-Wing

This focus on the player-as-creator unabashedly borrows from Fan Studies, which posits viewers of pop culture texts as co-creators with the hegemonic directors, writers, network executives, etc. (See Henry Jenkins’ Textual Poachers, a seminal text in fan studies.)6If we allow that the game positions the players of X-Wing as behind-the-scenes model-builders, then we accept them as fan co-creators in a classical fan studies sense.

The notion of the player positioned as filmmaker extends beyond the links to the physical models and a single photo in a rulebook. The game’s reliance on a hidden-movement system creates a cycle of building and breaking tension as each ship’s movement is selected in secret, then revealed. In a well-played game of X-Wing, players will be attempting to outguess each others’ movement selections. A well-chosen maneuver at a critical moment in the game can condemn its chooser to defeat or catapult them to victory. These moments of tension parallel the structure of a Hollywood movie, with its sequence of buildups and reveals. Each player is making a movie, containing surprise twists and dramatic reveals, for the audience of their opponent, even as their opponent is simultaneously making a similar movie for them.

This formulation serves to remind us that, when using a fan studies lens, the viewer (player) is in control of their experience of the text (game). Though we arrived at the X-Wing-player-as-filmmaker conception by letting the game set the terms of the player’s positionality, now that we have arrived here, we must give the players their due agency as a co-creators.

Indeed, though X-Wing is a game licensed by the hegemonic author/owner of the Star Wars franchise, it contains resources whose presence can only be considered subversive, giving the players incredible resources to re-play and re-mix Star Wars on their own tables. To understand these realities, however, we must detour into a brief history of the Star Wars canon.

Fire the Ion Canon!

Star Wars has had a long and contradictory history of canon, starting with Splinter of the Mind’s Eye,7a licensed novel released shortly after Star Wars (1977), which contained plot points that were quickly contradicted by the later two films in the original trilogy. The franchise’s major canonical, non-movie texts were (until recently) contained by the label “Expanded Universe” (EU). This label contained short stories, comics, and novels, all existing in a roughly contiguous diegesis. While some details may have been contradictory from one story to another, when a major character died, was injured, or turned from the light side to the dark (or vice-versa) in an EU story, they were dead, injured, or turned in future stories. Star Wars’ EU was a textbook example of a transmedia franchise.

Then, in December of 2012, Disney acquired Lucasfilm.8In preparation for new films, books, comics, and toys, the newly-sold Lucasfilm cleaned the slate: Less than two years after the acquisition, all Expanded Universe stories were re-branded as non-canonical “Legends.”9These books, comics, etc. remained available, but the events that they describe are, from a canon standpoint, nothing more than well-produced fan fiction.

X-Wing is a collectible miniatures game. Unlike a more static board game product (but similar to a collectible card game or living card game model), numerous expansion sets, released at timed intervals, are a part of the game’s overall experience. Fantasy Flight Games publishes these sets in “waves,” each containing two to five expansions that are made available to players simultaneously. The game’s first few waves of expansions (2012 – 2014)10consisted entirely of ships that had been seen on-screen in the original Star Wars films. By the middle of 2014, however, FFG had exhausted the most recognizable in-movie starships, and included a ship that had only been seen in extra-filmic texts: the HWK-290, first featured in Star Wars: Dark Forces (Lucasarts, 1995). The game’s fourth wave contained no ships that had been seen in any Star Wars movie, and subsequent waves mix ships from the (newer) films with ships featured in Expanded Universe / Legends stories.

This inclusion of dubiously-canonical narrative items and characters in toy releases is not unusual. Transmedia franchises tend to value sales over strictly defined canons, and tend to leave the discussion of canon in the hands of fans, rather than containing it within in marketing materials. Nonetheless, Fantasy Flight Games, in an advertising update for an X-Wing expansion pack, gives a subtle nod to the game’s situation of itself between the new canon and the Legends canon: “There are many legends in the Star Wars galaxy, and while they aren’t all true, there’s generally a kernel of wisdom hidden within all the most durable of these legends.”11 By acknowledging that some pieces within the game are not canon (or, at least are part of the second-tier “Legends” canon), Fantasy Flight is acknowledging, from a position of hegemony, a reality that fan studies usually considers the province of the fan re-writer: Canon is rewriteable.

I Will Become More Powerful…

By situating players as filmmakers, and by giving them tools to mix and match canon and non-canon elements, Fantasy Flight Games has created, in X-Wing, a fertile ground for fan activity. Players can re-mix narratives, fielding an E-Wing (the old-canon replacement for Luke Skywalker’s classic X-Wing) alongside a T-70 X-Wing (the new canon’s answer to the same narrative issue), or compress timelines, putting new-trilogy villain Kylo Ren in the pilot’s seat of a shuttle and recruiting his long-dead grandfather Darth Vader to crew that same shuttle. These “incorrect” uses of the Star Wars canon abound, as players attempt to optimize their squads for tournament play, or create new narrative scenarios not present in the films. Indeed, the game has so many waves of upgrades drawing from so many different sources, both Legends and new canon, that some X-Wing players intentionally limit players to using ships seen onscreen in the original three Star Wars films: “…it’s going to be the good guys versus the bad guys like in the movies.”12That this game could become so sprawling as to engender this playfully reactionary development speaks to its willingness to engage and embrace fan activity. By allowing non-canonical ships, characters, and pairings, Fantasy Flight Games has recognized the power of fan activity, and the importance of situating the player in a place of power.

Though X-Wing’s positioning of its players at first seems mysterious and perhaps even constraining, using the lens of fan studies and the notion of viewer-as-co-creator (player-as-filmmaker), we can see that X-Wing positions its players as directors. The hegemonic controllers of the Star Wars universe recognize that, though they can control their story on a macro level, the fan’s imagination (as embodied on their game table, covered in licensed X-Wing ships) is, to a certain extent, beyond their control. By refusing to limit players of X-Wing to the strict confines of a starship cockpit, and by providing them with a broad palette of options, the game authorizes players and fans to do what players and fans do, whether authorized or not: Play with and re-write their favorite movies.

–

Featured image “X-Wing Fighter” by David Pinkney @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND

–

Greg Loring-Albright is a student in the Communications, Culture & Media PhD program at Drexel University in Philadelphia, PA. He makes tabletop and pervasive games, most recently “Leviathan,” published by Past Go Play, an asymmetrical card combat microgame inspired by Moby Dick. Find him on twitter @gregisonthego participating in coffee- and gaming-related chats.

The initial part of the article argues that the player is positioned as a producer. Part of the argument is that there is no clear fictional location for the player.

It would be interesting to know how other miniature games handle the issue of placing, or not placing, the player into the fiction. It might be that it is a common abstraction in the genre of games to simply ignore this issue, or it might be that the issue is usually addressed.

Greg Loring-Albright, thanks so much for the post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.