Before the first turn was over, I knew I had won—a circumstance typically only achievable through overwhelming skill, prognostication, or cheating. In this case, however, the game itself gave me an insurmountable advantage via my starting position. It’s tempting to label this as poor game design1 since it certainly violates the principle of fairness almost universally assumed in competitive gaming. Yet in a world where the myth of a ‘level playing field’ obscures and authorizes ongoing social inequalities, problematizing the notion of ‘fairness’ in gameplay may provide unique insight into the ‘fairness’ of capitalist culture. This insight is possible because contemporary games are cultural phenomena that have also become media phenomena. Games, that is, need not merely reflect culture, but have critical potential for reflecting on culture. The following reflections work toward developing such a critical paradigm by showing how the Oil Springs scenario for The Settlers of Catan plays out ethical dilemmas raised by the emergent and systemic inequalities generated by capitalist systems.

In order to analyze these inequalities, this paper first explores game balance as the interplay between emergent inequality (how games determine winners and losers through the inputs of skill and chance) and systemic inequality (how an asymmetrical game state may privilege certain players).2 This paper then analyzes how the Oil Springs scenario for Catan links resource generation to land ownership, the runaway leader problem to the tendency of capital to accrue capital, and industrialization to market destabilization and ecological catastrophe. Finally, I reflect on the experience of enacting inequality within an unbalanced game system. Throughout, I suggest that while competitive games are typically designed to produce emergent inequality from within a level playing field (systemic equality), the rules that govern such emergent inequality are systemic in ways that allow for critically engaging systemic inequality.

Fair and Balanced

While not all games are competitive,3 the history of games is thoroughly intertwined with agon (or ‘contestation’) as an organizing principle of Western culture. According to French sociologist Roger Caillois, agonistic games play out agonistic culture “like a combat in which equality of chances is artificially created, in order that adversaries should confront each other under ideal conditions, susceptible of giving precise and incontestable value to the winner’s triumph.”4 With mathematical precision, agonistic games create balanced contests that reflect the ideal of agonistic culture: a perfectly level playing field that produces a genuine meritocracy. Yet, even while reflecting this agonistic ideal, the complicated balancing act performed by actual games demonstrates the limits of this ideal. Recognizing that fairness is problematic even within the carefully-controlled medium of games should also call into question the very possibility of a level playing field in arenas as complex as global capitalism.

Fairness, like beauty, is left to the eye of the beholder. What standards determine which is most fair: that everyone gets the same amount of pie (equality), that everyone gets pie according to their need for pie (equity),5 or that everyone gets pie in proportion to how much money or labor they invested in the pie (meritocracy)? There are similarly divergent ways of considering fairness in games. Caillois is adamant about the fundamentality of fairness, arguing that games of both skill and chance (agon and alea) “require absolute equity, an equality of mathematical chances of most absolute precision. Admirably precise rules, meticulous measures, and scientific calculations are evident.”6 Taken together, however, skill and chance presuppose contradictory paradigms of equality, making it difficult to determine what counts as fair for games that incorporate both (as most contemporary tabletop games do). Similarly, although Caillois argues that “The search for equality is so obviously essential to the rivalry that it is re-established by a handicap for players of different classes,”7 notion of fairness behind the handicap does not reinforce but rather undermines the agonistic ideal. Such contradictory messages suggest that fairness is a highly subjective notion. That is: standards of fairness vary not only according to individual preferences, but also by context (casual gaming vs. tournaments), game genre (wargames vs. party games), and even circumstance (games are generally only ‘unfair’ when one is losing).

Unsurprisingly, this variability amongst subjective standards yields a spectrum of paradigms for promoting balance, a somewhat vague negative term that presents fairness as ‘not unbalanced.’ Most commonly, games that tend towards symmetry tolerate emergent inequality but very little systemic inequality: symmetrical games allow skill and chance to separate players as the game progresses, but provide roughly parallel pathways to victory. In such games, the inevitable asymmetries are typically either minimized (playing first often confers an advantage, but usually a minimal one) or counterbalanced by other asymmetries of relatively equal value (the komi in Go compensates black’s advantage in going first with a point bonus given to the white player). Asymmetrical games extend this latter technique by counterbalancing different ways of playing (via differing pieces, abilities, rules, goals, etc.) to create a more or less equal game balance. Thus, asymmetrical game design provides two possibilities for exploring systemic inequalities. Balanced asymmetrical games can explore themes of inequity while maintaining an environment of fair play that adopts a perspective of critical distance—the player observes the interplay of differences that contribute to inequity without being immersed in the experience of inequity itself. By contrast, deliberately unbalanced asymmetrical games can explore inequity both thematically and procedurally, immersing players in a fundamentally inequitable world.

To advocate critical play with and against capitalist systems, there are good reasons to challenge any standard of competitive balance that supports the myth of capitalism as a level playing field. Insisting on perfectly balanced games is not just an impossible ideal; it is a problematic one. Balanced games imagine idealized worlds that may reinforce the deep cultural assumption that contestation is a practical and ethical way of organizing society. Yet, there is a substantial disconnect between the fair and balanced worlds of gameplay and the many systemic inequalities that emerge in everyday societies. In practice, major genres of competitive game design—such as wargames, race games, betting games, and economic strategy games—often uncritically invoke and thereby reinforce broader forms of cultural contestation. Strategic wargames, for example, may intellectualize war tactics while glossing over the cost of violence. Similarly, economic strategy games may glamorize profiteering while failing to represent exploitation. For instance, Monopoly depicts rents as an arena for capitalist competition but ignores the consequences for tenants, worker placement games often reinforce the dehumanizing representation of laborers as human resources,8 and Catan fails to represent the violence of settler colonialism.9 And even as these games ignore disenfranchised populations, they ask players to become complicit in the systems that produce such disenfranchisement: the participatory medium of games often entangles player agency with the logic of capitalism by promoting a particularly capitalist model of agency—a self-interested agonistic impulse that plays out within a quantifiable, rule-governed system of exchange.

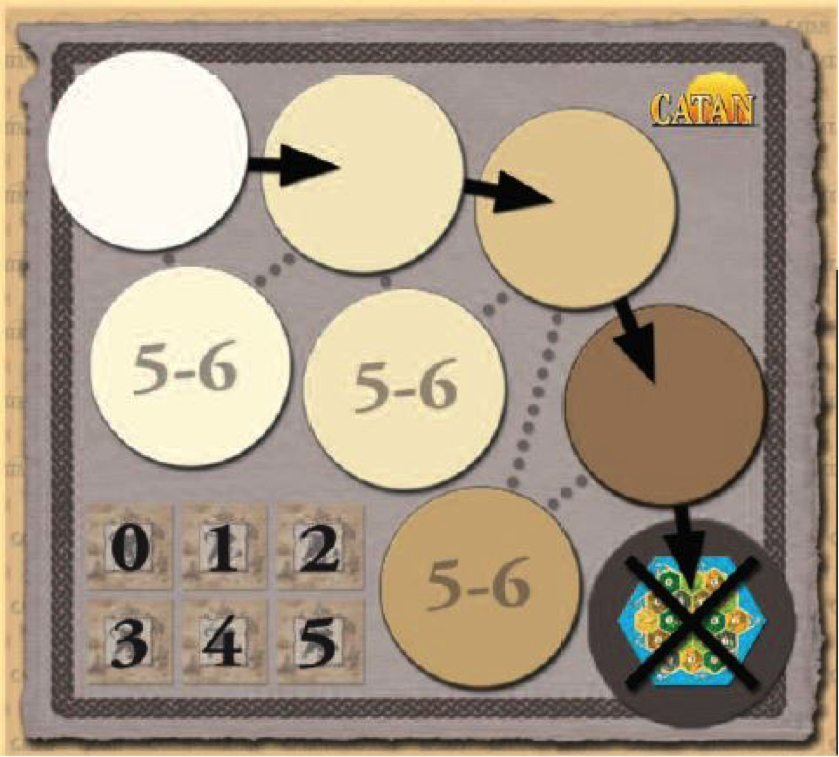

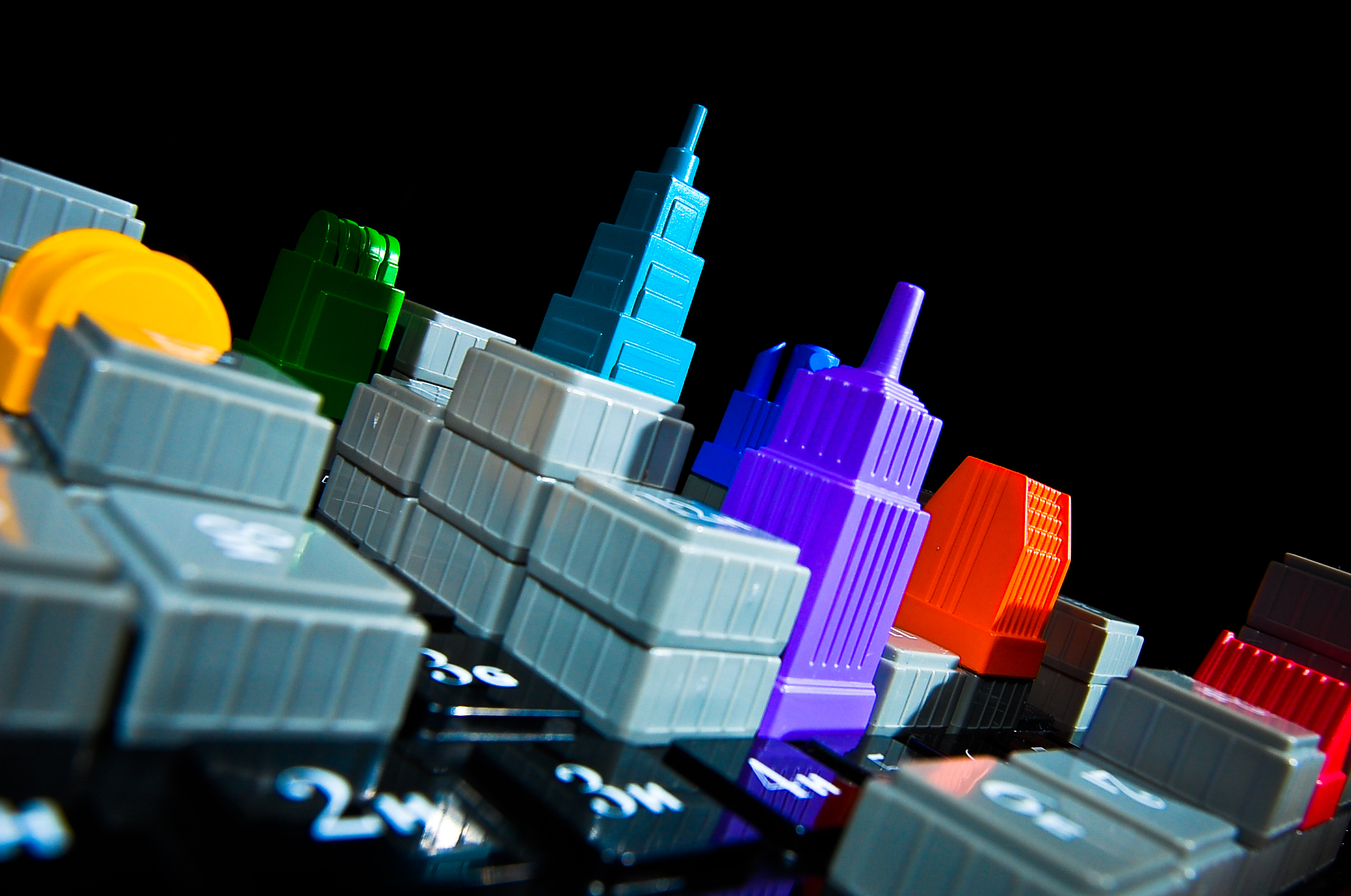

Although the way that games are more generally implicated in capitalism10 (and vice versa)11 deserves more critique, this parallelism may also provide games like Catan with a special critical potential to expose systemic inequality. For instance, in The First Nations of Catan, game designer and scholar Greg Loring-Albright describes how he developed “a balanced, asymmetrical strategy game” that “creates a narrative for Catan wherein indigenous peoples exist, interact with settlers, and have a fair chance of surviving the encounter by winning the game.”12 As discussed above, this type of game represents a critical intervention into historical inequalities while minimizing systemic gameplay inequalities, such as ones that might give the indigenous peoples a less than “fair chance.” By contrast, Catan and its Oil Springs scenario are mostly symmetrical and, if not actually unbalanced, certainly balanced unstably. With respect to Catan, Oil Springs makes more explicit the thematic connection to capitalism and, in a related move, makes the game balance even less stable “to draw attention to important challenges humanity faces, in relation to the resources that modern society depends on.”13 It accomplishes this by adding to the five original pastoral resources in Catan the modern resource of Oil, which is simultaneously more powerful (it counts as two standard resources), more flexible (it can be used as two of any resource), and more dangerous (its use triggers ecological catastrophes). By raising the stakes in these ways, Oil Springs further unbalances Catan to make a point about emergent social inequality tied to the unequal distribution of resources.

Playing Capitalism

Capitalism is far too multifaceted for any game—even one with as many variants and expansions as Catan—to model fully. Yet, games can indeed critically play with capitalism by condensing capitalist principles into their game systems through the systemic constraints and affordances that structure game interactions. Rather than describing capitalism, many agonistic games are themselves simple capitalist systems in which self-interested players engage in more or less free market competition with each other. Certain game designs, therefore, are not only tied to the agonistic logic behind capitalism, but are unique microcosmic economies that can represent specific facets of capitalism. The abstraction of Catan, for instance, obscures the history of settler colonialism and the exploitation of labor to focus instead on portraying land ownership as a lynchpin of modern capitalism, both in relation to resource generation and the tendency of capital to accrue capital. Similarly, the mechanics in Oil Springs focus on the role of the natural resource of oil as fuel for industrial capitalism by showing how industrialization accelerates resource production and exploits the environment.

For Karl Marx, ownership of private property14 precludes fair compensation of workers by granting the capitalist (the holder of capital15]) legal ‘rights’ the value generated by production without requiring that they contribute any labor towards generating that value. Land in Catan reflects this model by automatically generating resources which are given directly to the player/landowner, completely bypassing the question of labor. Instead, the emergent inequality is between rival capitalists played by the game participants. Although class differences are not represented, these emergent inequalities are structurally linked with class differentiation. Indeed, private property is problematic for Marx primarily because it forms the conditions for emergent inequalities to become systemic inequalities through wealth consolidation. Thus, private property parallels an emergent asymmetry known in game design as the runaway leader problem, in which it becomes increasingly difficult to catch the lead player as the game progresses. This occurs in any game design—such as Catan—that links point accumulation and resource generation, creating a feedback loop such that the further one is towards achieving victory the more resources one gains to reinvest in that progress. In contrast to a game like Dominion, in which accumulating victory points can actually reduce the effectiveness of one’s resource-generating engine, in Catan the closer one is to victory the faster one should move toward victory.16 The idiom it takes money to make money captures this fact about capitalism, which Marx describes as “the necessary result of competition” being “the accumulation of capital in a few hands, and thus the restoration of monopoly in a more terrible form” (70). In fact, emergent and systemic inequalities often do synergize in this way as the material consequences of emergent inequalities become concretized as systemic as they are passed down from generation to generation, maintaining fairly resilient wealth disparities between different social and ethnic groups.

For Marx, these problems with land ownership are only intensified in industrial capitalism, in which ownership over the machinery of production further disenfranchises the industrial worker. This is precisely the shift in emphasis behind Oil Springs, which introduces Oil not just as one more roughly equivalent commodity, but one which radically unbalances Catan’s market economy. Representing the increasing pace of production from pre-industrial to industrial societies, one unit of Oil is worth two resources. In fact, it is worth two of any resource, which means that the strategic value of a single Oil resource ranges from two to eight resources (since it can take up to 4 resources to trade for a resource of one’s choice), making Oil so much more valuable than other resources that it seriously unbalances the game. In addition, Oil is required for building a Metropolis, the most powerful building in the game. Depicting how new industrial processes destabilize existing economic relationships, Oil Springs shows how the problems of capitalist land ownership are compounded when such land contains scarce resource reserves that are essential to industry. Such resources encourage relationships of dependence not only over renters and laborers (who are nowhere represented in Catan), but also over other industrialists who require these resources. Thus, the game makes the inequality between different starting positions more dramatic to depict a shift in modern geopolitics away from territory being valued primarily for it land, population, and location to being valued primarily for its strategic resources.

While Oil Springs does have mechanisms that restore some balance, such as keeping Oil off the highest-probability hexes and capping the amount of Oil a player may hold at one time,17 its primary mechanisms for balancing Oil ironically further unbalance the game. By making Oil use precipitate ecological disasters, Oil Springs highlights the costs of industrial capitalism and makes an implicit ecocritical statement about how environmental consequences affect us all. They affect us, that is, randomly but not equally. Demonstrating that even negative consequences can be exploited by the industrial capitalist, the game’s two forms of environmental disaster turned out to be less damaging to me than to other players. The first environmental disaster, in which rising water levels destroy coastal settlements, played in my favor because I planned to exploit Oil and therefore avoided building coastal settlements.18 The second disaster, representing ‘industrial pollution,’ randomly strikes individual hexes, causing them to permanently cease to produce resources. More precisely, it does this to the ‘natural’ resources—affecting all hexes except for Oil Springs, which continue to produce after a reduction in the shared Oil reserves. Thus, because I was disproportionally less accountable for the consequences of my actions, I was able to safely initiate risky behavior that the risk-averse players suffered from. As risk and accountability can become unhinged in a free-market society that pushes for deregulation, Oil Springs speaks to the fact that those most responsible for climate change—be they individuals, corporations, or nations—do not generally bear the brunt of the consequences.19

In all the aforementioned ways, the game systems of Catan and Oil Springs use emergent inequalities to reflect on various systemic inequalities. This conflation, however, raises another question of fairness, namely how systemic inequalities emerge. In the case of Catan, this question becomes how to distribute land that has such intrinsically unequal value that it is sometimes possible to accurately predict the winner based on the starting positions (as in my case). The game attempts to solve this by using a snake draft to organize how players select their starting positions. Fairness is achieved not by creating equal spaces, but by assigning fundamentally unequal spaces using the mechanisms of emergent inequality: skill and chance (agon and alea). There is a fundamental difference, however, in the role these two forms of emergent inequality play in the deep interpenetration of games and culture. For Caillois, whereas agonistic games reflect the meritocratic ideal of cultural contestation, aleatory games play with the fundamental uncertainty of life—they are ludic, even carnivalesque experiments in fatalism. Unlike the triumphalism of agon, therefore, the aleatory elements of games explore consequentiality beyond the limits of human agency. This explains, for Caillois, how aleatory social institutions such as gambling and lotteries counterbalance the fundamentally agonistic structure of society by providing a faint hope that any individual may leap out of a condition of systemic inequality through an emergent (but rare) inequality. This demonstrates how capitalism balances itself by using the possibility of upward mobility to obscure its systemic conditions for economic immobility.

This also reveals a way in which game design struggles to represent systemic social inequality: games often achieve balance by using aleatory elements to subsume systemic inequality within emergent inequality, sacrificing the critical experience of systemic inequality in order to maintain the ideal of balance. Thus, the emergent inequalities in Catan fail to represent how historical inequalities are invariably systemic as race, gender, class, and nationality play prominent roles—how in America, for example, the original occupants were dispossessed by force of arms and land was redistributed according to explicitly discriminatory laws.20 It also fails to represent how even after more recent legislation has eroded many of these practices, their legacy21 necessarily lingers within a capitalist system where ownership is passed down from generation to generation. There are limitations, therefore, to representing social inequality exclusively through emergent mechanisms—when games create a genuinely level playing field, they become incompatible with capitalism, which perpetuates the myth of a level playing field while in fact perpetuating systemic inequalities.

Playing with Privilege

It was only upon further reflection that I began to tie my play experiences to the preceding forms of social inequality. In the moment, however, my focus was more narrowly focused on executing my strategy—or, to put it bluntly, on winning. At the same time, this was tinged with a growing sense of discomfort that can only be described by an even more uncomfortable word: privilege. Certainly, my ability to win the way I did was due to a privileged starting position, which tilted the balance of power in my favor. Yet, privilege is an attitude as well as a condition: being able to focus exclusively on strategy and winning is itself a form of privilege. Games (even so-called serious games) are not theories of social inequality—as embodied, performative spaces, games express a procedural rhetoric22 in which players develop perspectives by exploring the consequences of their decisions and actions as they play out within the game system. To play certain games in certain ways, therefore, is to play as capitalists and play out capitalism.

As mentioned above, the procedural rhetoric of Oil Springs is paradoxically predicated on privileging the very strategies of industrial capitalism that this ecocritical game otherwise censures. This presents players with a dilemma, in which playing to win may require performing actions that are thematically represented as ethically problematic. Thus, the primary reason I received such advantageous placement in my case study is that I ruthlessly pursued Oil from the start, whereas several of my opponents hesitated to do so (possibly due to their ecological consciousness). Sometimes gamers attempt to justify a win-at-all-costs mentality by claiming they are merely following the dictates of the game (indirectly valorizing the cultural ideology of agon), or that they are merely solving an abstract puzzle without regard to thematic considerations. While these are valid ways to play a game, they nonetheless represent an active choice on the part of the player rather than some ‘objective’ or ‘default’ position. Indeed, the phrase “win at all costs” itself admits that such play necessitates a cost. While I can understand why some players would choose to play in this way, this position is not viable for game scholarship. To properly study a game, one must account for the interplay of its many facets. Theme, which can evoke representational content and complex psychological and affective23 responses, is an essential facet of a game as text. When players respond to a game’s theme, they are performing a genuine textual engagement worthy of analysis. Thus, this section draws on my own play experience to reflect on possible consequences of systemically privileging certain positions.

If I had to sum up my experience, I would say that playing and subsequently winning this particular game was no fun at all. And, although I cannot speak for the other players, I imagine it was not much fun them either. Working from an advantaged position altered the game experience in ways that counteracted much of the enjoyment I typically derive from gameplay. I say ‘working from’ rather than ‘playing from’ because rather than playfully exploring new strategies, I found myself merely implementing the most obviously advantageous strategy. My narrow focus on winning imposed an inappropriately results-driven framework on play, something I typically value more for the experience than the results. This focus was driven, moreover, less by the rewards of victory than by the fear of failure24—even while my privileged position robbed winning of much of its merit, losing would have been still worse. Although the game was unbalanced in my favor, an increased probability of winning did not, in my case, lead to an enriched game experience. This is because the value of a game experience cannot be reduced to winning, which is why games—even agonistic ones—are distinct from non-playful tests or contests. This is surprisingly analogous to Marx’s argument that capitalism not only inequitably distributes resources, but also reduces human experience to something instrumental and transactional. Indeed, Marx suggests that even while the capitalist is materially advantaged over the laborer, both are equally alienated by being reduced to their respective roles within the capitalist system. Systemic inequality, that is, is dehumanizing for all its participants—whether privileged or marginalized.

Systemic inequality in games is, of course, less consequential and more voluntary than social inequalities,25 but it can alienate players in similar ways. In fact, most games eschew systemic inequality because it tends to be unpleasant for everyone involved. Players in privileged positions may find their roles overdetermined by the game structure, resulting in a narrowing of strategic, exploratory, or playful possibilities (for example, I had no reason to trade with other players when I could acquire all the resources I needed on my own). Similarly, players in less privileged positions may find their choices narrowed by their limited resources as the runaway leader problem renders their choices increasingly inconsequential. Systemically unequal game design, that is, looks like a lose-lose situation. Yet, it is not that inequality deprives play of choice, but rather that it overdetermines the consequences or relative viability of various choices. In the right conditions, therefore, such unbalanced play may add a unique dimension to the play experience. Rather than playing as an industrial capitalist, for instance, I could have chosen to play as an environmentalist. Instead of using Oil, I could have chosen to ‘Sequester’ Oil by permanently removing one of my Oil resources from the game each turn, gaining 1 Victory Point (VP) for every three Sequestered Oil, and an additional VP for sequestering the most Oil. Simple mathematics suggests that this is a terrible strategy: 1 VP is a paltry reward for the relative value of three Oil.26 This discrepancy underlies a model in which industrial capitalism is systematically more viable than environmentalism. Yet, what counts ‘viable’ can be called into question. Precisely because sequestering is ‘bad’ strategy, it offers an interesting thematic possibility: role-playing as an environmentalist knowing that one is not likely to win. From a thematic perspective, this strategy could be quite rewarding. Whereas my privileged play would lead either to failure or a victory deprived of merit, pursuing sequestering could offer either an impressive victory or a loss offset by the satisfaction of maintaining a moral position.

These benefits, however, are psychological rather than ethical. While environmentalism is certainly much needed, playing environmentalism in a game is no more intrinsically beneficial than playing industrial capitalism. Critical gameplay requires more than importing real-world values into games; it requires interrogating the assumptions players bring to the game and the positions they adopt within the game. To sequester Oil solely for the sake of feeling morally superior is not a critical position (although it could certainly be an attractive one). Precisely because environmentalism matters, it deserves critical attention and critical gameplay. After all, activism can be problematic in, for example, replicating colonial attitudes towards the developing world or performing a kind of ‘conscience laundering.’27 Critical play,28 that is, is not an outcome but a method. Or, as Marx puts it, “I am therefore not in favor of setting up any dogmatic flag. On the contrary, we must try to help the dogmatics to clarify themselves the meaning of their own positions” (13). The potential consequences of such reflection are not just two, but many. Beyond simply stating that one way of playing (environmentalism) is superior to another (industrial capitalism), critical play provides an opportunity for players to self-reflectively engage the decisions and feelings of occupying different subject positions within inequitable systems.

Coda

Games have not historically been on the forefront of discussions on social inequality.29 This is partially because the fundamentality of agon in games reinforces certain cultural logics, partially because the carnivalesque nature of play tends not to revolutionize prevailing systems,30 and partially because social inequality presents a special challenge for game design. To reverse this trend will require a critical perspective that pushes the limits of the game medium, such as the imperative toward balance at the heart of competitive game design—especially in a world where ‘fairness’ alternatively means ‘light-skinned,’ and the myth of a level playing field is used to justify a clearly uneven one. As Oil Springs demonstrates, experimenting with the interplay between emergent and systemic inequality is one way games can explore capitalism as similarly rule-governed, self-interested systems. In deconstructing the myth of the level playing field, it becomes clear that emergent inequalities in capitalism are develop systemic qualities. As a rule-governed agonistic system, capitalism legally positions the capitalist to leverage the rights of ownership to exploit the worker’s labor. Similarly, capitalism promotes the runaway leader problem by passing down capital via inheritance rather than need or merit. Furthermore, despite all claims to neutrality, economic hierarchies in capitalism are historically intertwined with other social hierarchies, such as race and gender. The problems of social inequality, therefore, are necessarily multiple and intersectional.

Games have historically also lacked nuance with respect to intersectional analysis.31 If they represent categories like race and gender at all, most games do so either via problematic stereotypes or via visual and narrative means that bypass the procedural rhetoric that makes games so distinctive. I suspect that most game design avoids systemic unfairness at the level of identity politics to avoid alienating players who identify in diverse ways. At least on the surface, class—an extrinsic marker of social identity—seems easier to dissociate from sensitive identity politics and, thereby, more implementable in games like Catan.32 However, critical play must resist the ways that games by their nature simplify and abstract what they represent. Instead, critical play draws upon but moves beyond such simplification and abstraction to respond to complex social realities. And the reality of capitalism, as discussed above, is that class is intertwined with race and gender. Indeed, an intersectional perspective on critical play may provide a way of exploring the paradoxical unity and disunity of player and role that complicates the gameplay experience. After all, despite the common association between criticism and distance, critical play is still an experience—an embodied calling into question of certain social systems.

–

Featured imaged “Giant Settlers of Catan” by Ethan Trewhitt CC BY-NC-ND.

–

Jonathan Rey Lee, PhD is a comparatist currently researching toys and analog games, especially as performative sites for transmedia, narrative, and philosophical engagement. He received his PhD in Comparative Literature from UC Riverside and currently resides in Seattle. He has written (and is still writing) on LEGO and his paper “The Plastic Art of LEGO: An Essay into Material Culture” is available in the Design, Mediation, and the Posthuman anthology. Jonathan can be contacted at https://ucriverside.academia.edu/JonathanLee.

This is so good! I know this post is over a year old but I just stumbled upon this blog and this caught my eye because I’ve been saying the same thing about Catan for a long time… I wish this topic were raised more in the game community, so thank you for your extensive analysis and putting all of this so elegantly into words.