In his monograph The Art of Failure, Jesper Juul argues that while failing in gameplay is necessary to produce a fulfilling experience, “it is always potentially painful or at least unpleasant.”1 According to Juul, because modern video games are designed to be winnable, failure highlights the insufficient ability in the player– it produces discomfort but also motivation to close the challenge-skill gap. Becoming better at the game through repeated play then results in the pleasure of escaping defeat. As Bonnie Ruberg notes,2 Juul and others in game studies assume that fun is what players are after, and though losing isn’t fun, it is at least helpful in leading to the fun of eventual victory. This “paradox of failure” as Juul calls it appears to extend well beyond the sphere of gaming. For example, entrepreneurs and designers are encouraged to “fail faster” in order to reap the lessons learned that will propel one to ultimate success.3 Buried within this advice is a pair of assumptions – first, that achievement is the point of it all, and second, that failure’s only value lies in what it can teach us about how to win. Juul argued that while he analyzed emotions in single-player and competitive multiplayer digital games, his analysis should apply to other play contexts. But we challenge the universality of this apparent paradox, both within and beyond the world of games. For example, writing about America’s views on failure, journalist Eric Weiner writes “We love a good failure story as long as it ends in success… In these stories, failure serves merely to sweeten the taste of success.”4 But other cultures do not necessarily feel similarly – according to Weiner, creativity flourishes in Iceland because of the admiration its people have for artistic expression, regardless of whether the product is deemed successful or not. It’s the attempt, the trying that matters. Just as failure cannot be understood through the lens of a single culture, we argue that an account of failure in gameplay is incomplete without considering how it feels to lose in diverse contexts. Although it is important to consider the individual experience of failure as Juul has, we aim to reconsider what might be uncovered by considering collaborative gaming experiences–we address this gap by uncovering the social and emotional space that failing together creates.

Cooperative board games have emerged in the last decade as a particularly popular and successful segment of the hobby tabletop game industry, especially since the release of Matt Leacock’s Pandemic, in which players attempt to save humanity from four rampant viruses.5 In cooperative board games, players work together against the game itself, typically discussing strategy and tactics with each other but playing their own moves, and then enacting the moves of the game’s “AI”. Failure is common in cooperative games because there is often only one victory condition, while multiple conditions will end the game in a loss. In this article, we describe the insights from a systematic exploration of how it feels to lose together, face-to-face, against a board game. We question Juul’s depiction of failure as an unpleasant means to an end, and focus on its inherent value as a rewarding emotional and social journey. When experienced together, both the process of losing and loss as a final result carry with them opportunities for camaraderie, humor, memory-making, and storytelling. In addition, the collaborative nature of the activity reduces the sting of failure through a shifting of focus from the self to the group. These findings reject failure as inherently or wholly unpleasant, and align with Ruberg’s point that, from the perspective of queer studies, winning is not even the goal for all players in the first place. An examination of cooperative gameplay provides a more nuanced view of how failure can feel–disappointing and frustrating, perhaps, but also potentially exciting, joyful, or simply unimportant. This lesson from cooperative play–that working together toward a goal is meaningful and impactful in itself–suggests that perhaps we can benefit from a more collaborative approach in our schools, institutions, and communities.

Crashing and Burning… Together

To better explore this question, we played four different cooperative board games several times.6 In total, we played four games a combined total of 12 times,7 with anywhere from one to five players (seven different players participated in at least one game session). Most commonly, the authors played together as a team of two. When possible, we played the games at the highest difficulty level. Eight of the twelve games ended in a losses, some worse than others. We played Flash Point: Fire Rescue (2011), Hanabi (2010), Reiner Knizia’s Lord of the Rings board game (2000), and Dead of Winter (2014) each at least twice. These games were chosen for their differences in theme, mechanics, and/or scoring. In Flash Point, players take the role of firefighters trying to save victims from a burning home before it collapses; the game emulates some of the mechanics found in Pandemic, such as each player taking multiple actions, and then playing the AI’s moves. Hanabi is a card game in which players can only see each other’s cards and must attempt to steer teammates toward playing the appropriate card at the right time by use of the very limited communication that is allowed. It has a very thin theme of building fireworks, and a scoring system for judging final performance. The Lord of the Rings board game puts players in the role of hobbits in Tolkien’s epic tale of Middle Earth, struggling toward Mount Doom to destroy the One Ring before they are overtaken by the Dark Lord Sauron and the evil power of the ring. Finally, Dead of Winter is a zombie-themed survival game which incorporates secret individual win conditions on top of a shared main objective, as well as the potential for one of the players to be a traitor (although in the two-person variant, the game is played in strictly cooperative mode with no traitor or individual objectives).

While playing, we experienced some emotional reactions that were consistent with Juul’s observations about difficulty and failure. For example, we observed that our emotional investment and immersion were dampened when we were able to handle the challenges and win easily, because the ‘crises’ did not actually feel dangerous (as was the case with our first play of Flash Point on the regular difficulty level). A sense of having ‘figured out’ the game can diminish interest in playing again.8 For players in this situation, most cooperative board games, like many single-player video games, offer a ready solution for this problem – increase the difficulty level the next time you play. In contrast, losses – especially when victory seemed within reach – tended to be motivating.9

As described earlier, Juul also describes the feedback that failure provides, which helps a player understand the game and the skills and techniques required to succeed:

Whereas success can make us complacent that we have understood the system we are manipulating, failure gives the opportunity to consider why we failed… Failure then has the very concrete positive effect of making us see new details and depth in the game that we are playing.<ref>Juul, p. 59.</ref>

Similarly, post-game analysis is a common, natural addendum to the cooperative board gaming session, particularly after a loss. Just as in competitive play, such as with a chess player pondering the moves made in a recent match, players can try to make sense of what went wrong, and when, and what strategies would lead to better performance the next time.

However, we also identified several features of cooperative board game play which serve to enhance the emotional experience of struggle and failure in a way that feels distinctly less painful than the experience of failure in video game play that Juul describes. And, in fact, players of cooperative games seem to want to fail, at least most of the time. A recent informal survey of nearly 300 hobby gamers suggest that roughly 80% of respondents prefer to lose more often than they win, and the most common preference was to lose 70-79% of the time.10 One possible reason for this willingness to lose, we believe, is that when people play, they have multiple goals (though some may be implicit), and victory is at best just one of those goals. Consider a group who are about to play a round of Pandemic. Goals for the session among the players might include winning, but also socializing with friends, taking a break from work or other responsibilities, engaging in a mentally challenging task with no ‘real’ consequences, exploring a new game system (for those unfamiliar to the game), teaching the game (for experienced players), and creating memories to reminisce about later. In light of all of these reasons for playing, if the game ends in defeat–as it does in this episode of the web series TableTop–the players are likely to experience both negative emotions such as disappointment or frustration, but also positive emotions such as social connectedness and vitality.

One of the hallmarks of cooperative board games is the dialogue players trade as they play. When we play by ourselves against others or against a computer opponent, we weigh the pros and cons of potential strategies we might employ and the moves we might make, as well as engage in an occasional accounting of how well or poorly the game is going. These thoughts represent a sort of internal dialogue with ourselves.11 The same kind of conversation takes place in cooperative board games, but in the form of an actual collaborative discussion with one’s fellow players. Joint decision-making can be both fruitful and eye-opening in and of itself. They prompt us to consider how different perspectives and ideas can yield even better ideas which no single individual would have come up with alone. In addition to the potential for improved play through coordinated strategy, this externalization and sharing can enhance how it feels to play (and often lose) the game.12 Certainly, the revelry associated with a group victory is often exhilarating. But struggling together against a cooperative game provides enjoyment in the form of collective tension and uncertainty as problems mount and the margin for error evaporates. Because of the slower pace in tabletop games, this tension and drama often feels sustained and extended in time. While death or defeat due to a wrong move can occur swiftly in many video games, in a number of our plays, we often spotted our impending loss well before it arrived. Additionally, players can easily put actual gameplay on hold temporarily while commenting on recent in-game events, the current state of the game, and their perceived chances of surviving the next crisis. Of all our plays, the most powerful and pleasurable was a game of Flash Point that we knew for the last 20 minutes of play we would almost certainly lose. On the verge of game-ending defeat for multiple turns, a string of good luck (including three potential victims consumed in the spreading fire which turned out to be simply false alarms) allowed us to draw out and savor the palpable despair, tinged with faint hope. The situation also drove home to us that if we were to have any chance of winning, we needed to work together to make the best possible moves.13

The rich communication and joint decision-making common to most cooperative board games also allow the player and her actions to become part of the collective whole. Although initial tactical options are usually generated by the player whose turn it is, this decision is ultimately chosen in consultation with her fellow player(s). We regularly experienced collective ownership over our entire play so that our failures were shared and exempt from the self-evaluative process that typically comes with active performance. According to the pioneer of flow research, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, this loss of self-consciousness is one of the key features of deep enjoyment of an experience:

Because enjoyable activities have clear goals, stable rules, and challenges well-matched to skills, there is little opportunity for the self to be threatened… When a person invests all her psychic energy into an interaction… she in effect becomes part of a system of action greater than what the individual self had been before. This system takes its form from the rules of the activity; its energy comes from the person’s attention.14

We experienced a counterpoint to this feeling in our plays of the card game Hanabi. Hanabi relies on effective communication–properly signaling to teammates about the cards they should or should not play is at the core of the game. But because open communication is severely limited, there is much less room for the collaborative strategizing common to most cooperative board games. The focus of play thus resides more with the individual players, who are unable to contribute to or comment upon each other’s planned moves. Like trick-taking card games such as bridge, or sports like doubles tennis, players are working toward a collective team goal, but doing so individually. For this reason, failure can produce the unpleasant taste associated with the awareness of personal shortcomings.

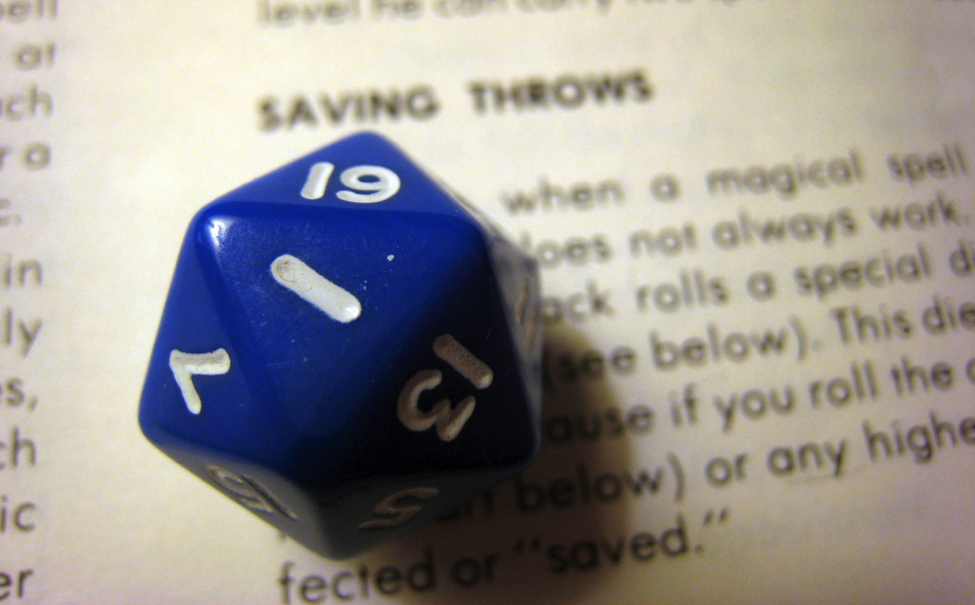

Again, while Juul describes failure as painful or unpleasant, he regards it as valuable and even necessary for the feedback and motivation necessary for ultimate triumph. But while both he and Koster have focused on the instrumental value of player failure for learning and improving one’s future play, in our cooperative sessions, we often experienced failure as a pleasurable social opportunity for banter, joking, and storytelling. Spectacular failure is just that–a spectacle to view and savor, and it turns out that, like most humor, it is best experienced with others. Because of the slower pace mentioned above, and the chance to detect defeat as it approaches, there is ample opportunity for players to commiserate over their misfortune, to identify the comedy within the tragedy, and to satisfy their curiosity not about whether the team will fail, but when and how the demise will play out (one fellow player admitted after a game that, upon judging that we were going to lose, he began secretly rooting for a particularly dramatic disaster to revel in). Taken together with the lowered self-consciousness and the observable vagaries of randomness from dice rolls and card draws, these features of cooperative board games make it particularly easy to experience camaraderie and humor with one’s companions. Indeed, the two solo plays that the first author engaged in – both losses – lacked the joviality and humor of our other failures.15

In addition to laughing off poor performance, players often construct a unique narrative to flesh out the actual in-game events. In a talk he gave at LinkedIn, Pandemic designer Matt Leacock explains his hesitance to design games with a built-in storyline; instead, he prefers to give the game a solid premise, and let the players tell the rest of the story with each game they play.16 Players are not weighed down by a dominant narrative and are free to add their own flavor and personality to the plot of the game. In other words, in addition to the strategic collaboration in trying to win the game, players may also engage in a second, creative collaborative endeavor: interactive storytelling. As evident in the TableTop episode (shown below) the players embellished the story of the unfolding events through their roles (e.g., medic, researcher), current locations (e.g., Miami), and the names they gave to the four diseases (which are unnamed in the rules of the game). In our play of Flash Point, the three players ultimately lost when fire spread to the location of a victim–a cat who happened to be sitting on the toilet in the one bathroom in the house. This fire then caused an explosion in an adjacent space containing a “hazmat” (hazardous materials), which destroyed the bathroom and its contents, and then led to the collapse of the entire building. Although play had ended and the game was lost, the game session’s highlight was this unlikely chain of events. The social nature of cooperative board games gives players the space to turn a devastating defeat into an amusing and memorable narrative.

Intra- and Extra-Game Considerations

While the features described above set the stage for pleasurable struggle in cooperative play, the in-game, social, and physical environments strongly impact the emotional experience of the players beyond what happens in the game world. In this section, we show how emotional experiences are related to the game mechanics of the particular game being played, and the dynamics of those doing the playing.

Each game we examined contains a unique combination of mechanics and features that have the potential to impact the emotions we feel when we lose. For example, we found that scoring player performance may or may not detract from the enjoyment of tension as the game progresses. In Hanabi, once basic communication patterns are established, it is fairly easy to succeed, and the score at the end helps to distinguish the degree to which players have succeeded. As a result, an experienced group can play to beat a previous score, but the perceived stakes of play feel relatively low. On the other hand, in The Lord of the Rings board game, success is relatively rare, and the scoring track simply represents how close the losing group came to succeeding, so victory remains elusive as the journey is fraught with peril.

As another example, consider semi-cooperative games, in which one player may be selected through a secret and random process to play as a traitor, working from the shadows against the group’s goals (such as Dead of Winter) while attempting to prevent others from discovering the betrayal.17 The traitor mechanic affects the social dynamics of these games by sowing suspicion and mistrust in the player group. The “semi” in semi-cooperative provides added dramatic tension, but it may also prevent failing traitor-players from being able to engage in the open strategizing, joking, or storytelling that enriches the experience of failure.18

It is also worth considering whether the game provides a repeatable, self-contained experience, or a series of linked missions to be played in progression. Many video games are designed to be played through to completion, and failure results in a reset to the beginning of a section or the last save point. This lack of progress in an experience with this progressing, serial element almost certainly exacerbates the frustration associated with failure. Most card and board games are more akin to sports in that they are not completable in this sense–the conclusion of a single play session has no bearing on the next game’s state, which is simply reset back to a starting position. However, some recent cooperative board games, such as the Pathfinder Adventure Card Game and Pandemic Legacy emulate a campaign approach to gaming where progress is dependent upon, or at least impacted by, successful completion of the current scenario. Therefore, we hypothesize that in such games, the desire to move the game or narrative forward (and, in some cases, to continue the development of one’s character as in tabletop roleplaying games) may prevent failure from being as enjoyable or entertaining.

Finally, it is no secret that the broader player relationships and dynamics have an enormous impact upon how playing feels, and this is true of how failing feels as well. Tired or disinterested players, long playtime, or significant player downtime between turns (all of which happened when playing Dead of Winter on a weeknight with a full group of five players in a dimly-lit lounge) can drain interest and weaken any tension or immersion associated with failure or near failure. Conversely, deep familiarity and friendship with one’s fellow players likely allows for an enhanced social experience – for example, laughter is more contagious among friends than strangers.19

Conclusion

In conclusion, our analysis of a dozen plays of various cooperative board games suggests that, at least within this subgenre of the tabletop gaming space, defeat is neither necessarily nor completely unpleasant. Rather, it has the potential to produce at least as rewarding a social gaming experience as a victory. The shift in focus from personal performance to collaborative action has the potential to remove much of the pain of losing, and even when we fail in our epic struggle against mighty foes and long odds, the pacing and social nature of cooperative board games provides a space for us to engage in fulfilling acts of camaraderie, humor, curiosity, and creativity. More generally, this exploration illustrates that by examining play within the broader interpersonal and motivational context in which it takes place, we gain a greater appreciation of the complexity and nuance of the resulting affective experience.

In her analysis of “no-fun” from a queer studies perspective, Ruberg argues that presumably natural player goals (e.g., to win, to have fun) and reactions (e.g., failure-induced pain) are in fact socially constructed assumptions of the way one does or should interact with games. She reveals that on deeper examination, individuals are free to (and do) exercise their agency in creating or playing games in subversive ways, such as a designer purposively building in an interactive experience that will elicit unpleasant emotions in the player, or a player choosing to pursue a goal other than victory or completion of the game. Ruberg’s point is that such choices and experiences are uglier than the normative message of “play to win, enjoy the ride,” but they are more authentic in the existentialist sense.20 Our own findings suggest a more subtle, less conscious form of rebellion – when working together toward a common goal, players may not only tolerate failure, but may be engaging in play for the purpose of something very different than the emotional spoils of victory. This runs counter to the messages we receive from professional sports (“The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat!”), political campaigns, standardized testing, and Wall Street, but investigations such as these underscore that social institutions need not repress failure or proscribe how we feel when we fail. In the context of education, for example, we can start from a more explorative, thoughtful, process-oriented approach. Learning in such a context, such as John Hunter’s world peace game,21 is difficult and rife with ethical and interpersonal struggles, but real and impactful. Such is the power of releasing ourselves from the bonds of the binary outcome and instead embracing the messy, human journey.

–

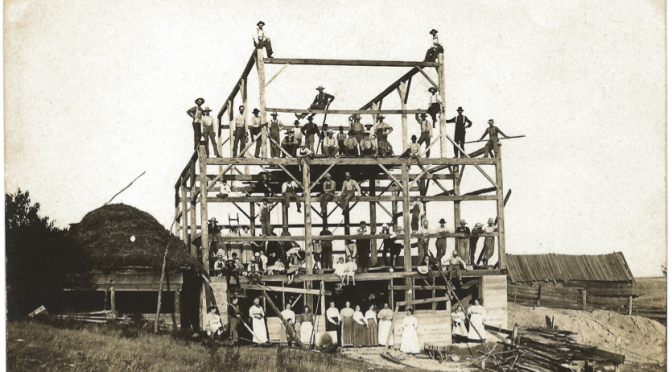

Featured image of a barn raising in Ludington, Michigan, USA provided by Don Harrison @Flickr CC BY.

–

Douglas C. Maynard, PhD is Professor of Psychology at the State University of New York at New Paltz. His scholarship lies at the intersection between game studies and positive psychology, and revolves broadly around the role of play, playfulness, and gaming in adults. He is Director of the Positive Play Lab, where he and his students conduct empirical research using a variety of methodologies to investigate the impact of analog game experiences upon emotional states, social connectedness, and well-being. Outside of academia, he co-organizes a local game designers guild and volunteers at his local library, introducing kids to modern board games.

Joanna R. Herron is a double major in psychology and mathematics, a tutor in the math lab, and President of the SUNY New Paltz chapter of SIAM (the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics). She also enjoy cooking/baking and spending time outdoors in her free time.

This also aligns with my experience that the least satisfying part of Pandemic is not difficulty, but the potential for back seat quarterbacking. So it’s not failure that makes it not-fun, but lack of agency.

The BGG survey should probably be tempered by the BGG crowd being more likely to be the people who buy and teach the games to their friends. When I’m teaching a game, I’d rather help another player win and get to play again than to win and have them not want to play.