My friend and I were 13 years old in 1992. His younger brother and a friend of his were 10 years old. We used to stay over for the weekend at their home in a smaller town, 45 minutes north of the city of Bogotá, where I lived. We spent hours reading the Player’s Handbook, to understand how we were expected to play. Once we had a grasp of it, we created characters and began playing. Every once in a while, we had to go back to the books, dictionary in hand, and re-check our translations. More often than not, we got it all wrong, and we played many times trying to make our translation work in our gameplay. This is probably how we learned most of our written English.

This brief excursion into my personal biography aims to bring forth an issue that was common among those of us who started engaging with role-playing games in the 1990s in Colombia. Our first exposure to the game had been different, but we had converged when we acquired together a copy of the Forgotten Realms Campaign Set to be played with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. My first exposure to anything close to Dungeons and Dragons had been an action figure of Elkhorn, the Dwarf, I received at a cousin’s birthday party (Cousin A), while my older brother had received Strongheart, the Paladin. It was probably 1984, and back then we had a confusing, yet attractive video game called Quest for the Rings (Magnavox, 1981), which our dad brought us alongside a Magnavox, Odyssey2 console. A few years later, another cousin (Cousin J) had some books of Aventura sin fin, the Spanish translation by the publishing house Timun Mas of Spain of the collection The Endless Quest. These short adventure books which required the occasional dice roll became our first experience of role-playing games. You can imagine the surprise when, a couple of years later, that same cousin brought a D&D adventure, “Quest for the Heartstone” which included the full character stats and pictures of Elkhorn and Strongheart! My cousin did not know that the adventure was only playable with the D&D rulebooks, so we engaged in a creative cultural translation of the adventure, mixing what we knew from the Endless Quest series and making do with only 6-sided dice.

All of this took place before 1987, when the TV show Dungeons and Dragons began broadcasting in Colombia under the translated title Calabozos y Dragones, and the whole thing began to make more sense. This transmedia experience of D&D is akin to the one presented by Evans, where the relationship with the D&D game playing experience came surrounded by non-D&D specific fantasy games, books, and TV shows.

In 1992 a friend from school who had recently come from the US had a copy of the Player’s Handbook of AD&D (2E) and had a set of dice. He had little to no knowledge of how to play the game, but with the book at hand we began our translation efforts. It was a demanding task, for we all had Spanish as our first language, and we were just starting our middle school English courses. In the Colombian system, where only international schools would provide full bilingual (Foreign Language and Spanish medium) courses, our twice a week one-hour course made us considerably underprepared for this project.

By 1993, we were regular players of AD&D (2E) following our folk-translation. It turned out that Cousin A had been into Role-Playing games, and I had no inkling about it. Working together with the then head manager of the only bookstore which sold RPG books – Librería Francesa – he launched the first D&D tournament in Bogotá, which I joined as one of the youngest players. This tournament eventually led to the development of the first RPG club – Trollhattan – and to the boom of Role-Playing games in Colombia.

Learning the language and translanguaging on the go

Although all this information may seem like anecdotal evidence, it sums up something that goes beyond personal experience. Take a look, for instance, at the Translating D&D Beyond Feedback Forum post by Warius:

“Hey! I’m a spanish-speaker from Mexico. I have no trouble understanding English and I grew up playing the game in English, making an effort to know the terms and eventually growing to feel familiar with them. D&D was actually one of the reasons I learned English in the first place.”

His experience, akin to mine and others’ in Bogotá in the mid-1990s, was that RPGs like Dungeons and Dragons allowed for the development of linguistic skills, as well as the creation of a frame of reference that has enabled the appropriation of a Euro-North American series of fantasy myths. Since the rulebooks for the RPGs were mostly found in English but actually played in Spanish, the whole process implied a form of code-switching or translanguaging –depending on your perspective – at the same time as appropriation of a mainly European-based fictional mythology.

The process was, then, a type of cultural translation or cultural transduction, in the sense that products from one cultural market (RPGs from the US or UK) found a way into, and an appeal in, a different cultural market (Colombia, in this particular case). Lacunae in the comprehension of the rulebooks came in two forms, using Rohn’s classification, as either a) content or b) capital lacunae. That is to say, Bogotá Role-Players either a) did not understand or like RPGs because of the activity it implied, its structure of play, or the characteristics of their content which they considered foreign, or b) because the cultural requirements for access (i.e. certain English reading proficiency, demanding reading habits and basic knowledge of fantasy settings/literature/film) were beyond their knowledge. The relatively small group of people that could satisfy the requirements for access –or who struggled strongly to acquire them– became, therefore, gate keepers that transformed the foreign cultural product into something they could all play together. This process required considerable transformation of the original texts and the creative folk translation of specific terminology, in such a way that it would suit the players’ needs, as well as remain coherent for all those involved in the game.

Following Uribe-Jongbloed and Espinosa-Medina’s classification, these gamers were effectively alchemists who would transform the information in the rulebooks and ancillary items into coherent game contents that could be discussed. Furthermore, they would meet beyond their limited gaming group or party with larger communities that joined gaming clubs or associations at the local or university level. At that stage, the translanguaging practices would develop more formally into a gaming slang that would include the appropriation of certain terminology, the normalization of English lexical items, the use of words in the foreign language but pronounced, most likely, in the local language –with a clear disregard for normative phonetics–and the development of verbs arising from the transformation of English verbs.

This is exactly what Warius describes in his forum entry:

“So, say that I decide to translate on the fly [from English to Spanish], which I have tried. The problem with that is consistency–As a TTRPG [Table-Top Role-Playing Game], D&D uses language and terms to refer to specific mechanics that everyone can recognize, things like Saving Throw, or the names of spells. If I translate the name of a spell one way, and then later my brother wants to refer to the same thing but uses a different word (because things can be translated different ways) it creates dissonance, because I might not recognize what he’s referring to and ends up dragging the game down. This also brings the problem of trying to refer to something as its translated name, and then having trouble referencing it in the book. If a player says to me “I want to cast *translated name of spell*” I have to mentally try to reverse-translate to look for it in the English book, and, again, things can be translated a ton of different ways. Just having a single point of reference at hand that we can all agree on would go a long way.”

This is not an issue that only happens between the named languages of English and Spanish. It also happens with other languages, as this other forum posts attest:

“I’m German and while I myself don’t have a problem using D&D Beyond – and D&D books in general – in English, my friends aren’t as fluent as I am. And even if they were, we would still speak German when we play. This went so far that three years ago when I introduced them to D&D and there was no translated version of the books, I would help them create their characters and then translate all relevant class abilities for them. I would even create little spell cards with the translated spell descriptions – and we had both a cleric and a druid, so that was a lot of writing.”

“I find that as a DM, the biggest challenge is translating flavour text on the fly. It might be boxed text or the more general information. My brain processed the text in English, but it doesn’t “spit out Swedish” unless i make it. It’s hard to explain, but it’s either in English mode or Swedish mode and it’s a bit sluggish in jumping between them.”

These perceptions are similar to those found in a small sample survey (n=61) carried out among Colombian Role-Players, conducted through a snowball sampling technique.Almost all respondents (60 out of 61) mentioned that they read the rulebooks and other materials in English, even when the game was played in Spanish. Most of them also commented on the use of specific terminology based on the requirements of the game, focusing on elements like the stats on the Player’s Record Sheets, the names of spells or weapons, and even referring to the name of the places. In fact, they also mention instances in which they dislike the official translation into Spanish found in some of the rulebooks (see Figure 1). In fact, in their own answers written in Spanish they use words like “stats”, “setting”, or “master”. They actively recognize they used lexical elements from English when playing, but they also include the translated versions of certain verbs as explained above. Their translanguaging practice included this ample lexicon, taken from the books. The fact that when they found out there were translations into Spanish they found unsuitable, reflects how languages are also anchored on collective cultural experiences, and many of them refer to the translations into Spanish as not being of good quality or just a general dislike of these versions.

Thus, more than code-switching between the named languages of Spanish and English, they show that their gaming jargon includes certain terminology, not because of their value as part or normative named languages, but rather because of the collective meaning they enjoy with fellow bilingual gamers with whom they can share their idiolect (see in bold the English elements in a common RPG session in Figure 1).

Looking at the practice of RPGs using translanguaging and idiolects, rather than concentrating on code-switching and named languages, becomes very useful here. Each idiolect expands its lexicon using the available linguistic opportunities: local Bogotá colloquial Spanish and formal, mainly American, printed English –with smatterings of names, expressions, and other bits and bobs from a variety of pop culture and fantasy literature influence, including artificial languages as Tolkien’s Quenya–, and rejecting formal printed Iberian Castillian translations. When these idiolects are set in play, they find common ground in the translanguaging practices of the Role-Players. Not all elements of the idiolects were accepted –I used to play with those who openly rejected the transformation into Spanish of verbs in English–, but there used to be no discussion about the constant use of many words in English during game play.

The RPG scene in Bogotá: Librería Francesa, Trollhattan, Camelot Millenium and Escrol

The rise of RPGs in Colombia in the mid-1990s came with the development of a new urban space for this social activity. The first place of note was Librería Francesa [The French Bookstore], a bookstore that would cater to the growing ‘nerd culture’ of the city. It sold the main RPGs of the time, as well as comics, graphic and fantasy novels –all in English or French–, and dice, figurines and other elements. When they opened a new branch in the city, they named it the Hobby Center, and it became a place where the Role-Players would find their equipment and engage in informal chat with fellow players. Much like the places described by Woo and Hermann, Librería Francesa allowed for those who could be considered “nerds” or “geeks.” Since “eventually ‘geek’ became synonymous with persons who collected comic books, were interested in computers, and otherwise engrossed with topics considered outside the mainstream,” Role-Players became part of the “geek” and “nerd” culture of the time.

But Librería Francesa and the Hobby Center did not have much extra space to receive groups of players. Regulars then opted to create their own places for gathering, and Trollhattan –the name given to the first Role-Playing club–, opened its doors in 1994. The site was an old mill in the centre of the city, on the slopes of the eastern ridge, a building owned by the Bogotá Waterworks. During the day, it operated as a restaurant which was managed by the father of one of the regular Role-Players of Librería Francesa.. Trollhattan would open on weekends for all-nighters. Club members paid a small membership fee and could buy snacks and soft drinks. In its heyday, it probably received about 200 guests a day. It eventually moved out of the old mill into a residential part of town, but the move was short lived. By 1997 Trollhattan closed its doors, but it had a strong impact on all those who played there.

Following the demise of Trollhattan, the new place to gather was Camelot Millenium. Camelot appeared at the same time as university student associations and guilds were being developed. Places like Avathor, the local RPG club at the Faculty of Arts of Universidad Nacional de Colombia, hosted the students by day, whereas Camelot would host them by night. By 1998, Camelot was acknowledged as the only public venue to play RPGs in Bogotá, and it was probably at the time where there was the widest interest on the phenomenon. Camelot did not survive for long either and by 2000 only the university guilds were active.

On February 22, 2001, a new gaming club appeared which would be the longest running of its kind: Escrol. Escrol –an acronym for Estrategia, Café y Rol [Strategy, Coffee and Role]– developed its name as a play on the English word “scroll” but using the pronunciation under Spanish phonemes. A few former members of Trollhattan founded Escrol in a residential neighbourhood in Bogotá where it hosted RPGs, Risk tournaments and Collective Card Games (CCGs) like Magic: The Gathering and The Lord of the Rings CCG. Escrol would have two incarnations, moving into miniature collectible games – such as Warhammer – and even some computer games. In 2007 Escrol finally closed its doors to the public.

These four places remain fundamental to most Role-Players today. A little less than half of those that took part of the survey (28 out of 61) mentioned Librería Francesa as the place where they acquired RPGs. Other places mentioned include online shopping (11), bought outside the country (7) or Escrol (3), with some of them mentioning borrowings or copies. Regarding the places where they used to play, the main entries are Trollhattan (11), Escrol (9), Avathor (3), Camelot (1) and Librería Francesa (1). Private homes (45) are the main place where people mention they played RPGs. The kind of intimacy of the private sphere that surrounded RPGs, being played at home or at a club, rendered it ideal for the display of personal idiolects, which could be shared with a small community without expecting any problems arising from differences in pronunciation (see Figure 3).

Role-Playing, Bilingualism, Class and Education

The locales where Role-Playing took place are relevant on two accounts: on the one hand, they were places located near the main universities or in middle-upper class neighborhoods, attesting to the class credentials that were almost always needed to be part of the bilingual community; on the other, they represented spaces of cultural elitism for the highly educated. Role-Playing in Colombia was thus mediated by class and education.

Class can oftentimes be measured by proxy with bilingualism according to school enrollment. In Colombia, one-third of secondary students are enrolled in private education. Based on school-leaving examinations of 2014, private school leavers fare better than their public school counterparts –especially in regards to English-language competence–, and the resources available in the classroom, more so than family and personal resources, are to blame for the gap.It can easily be said that Colombian high school graduate English levels are very low, lower than all neighboring countries, except for Panama. English proficiency is higher in international (bilingual) private schools, which are also expensive. Finally, the best results in English proficiency are to be found in the most demanding universities in the country, bringing bilingualism in line with education.

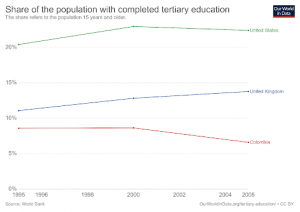

Colombia has a low rate of graduates from higher education. In 2003, 492493 people enrolled in higher education out of the 3.8 million people of the 17-21 age group, going up to 956106 out of 4.3 million in 2015. From 1995 to 2005 only 6-9% of the population over 15 years of age had completed tertiary education in Colombia – the US was between 20-23% and the UK 11-14% for the same period– (see Figure 4). Also regarding the percentage of people within 5 years of high school graduation, Colombia went from 16.15% in 1995 to 51.29% in 2014. The survey respondents included 28 people holding postgraduate degrees (PhD or Master’s), 30 with an undergraduate degree and 2 with a secondary degree out of 60 people who answered that question. This is quite important considering that in 2018 only 27151 graduated with a master’s degree and 803 with a PhD in Colombia. Although the small sample prevents us from assuming a direct correlation between post-graduate studies and RPGs, it does open an interesting avenue of research. Could it be that academic endeavours prompt RPG interest? Is it the other way around? Or is this a mere coincidence, like rolling a natural 20 on the d20 when expecting the most important saving throw in the game?

Discussion: RPGs and social elites

This paper began from my own experience to connect aspects that address the relationship between RPGs and translation in the form of performative translanguaging. Although the main subject at hand was the use of various linguistic repertoires during the sessions of role-playing in Bogotá from the mid-1990s onwards, it also brought up a concern that remains relevant in the present day, namely, who were the Role-Players and what social characteristics defined them and made their translanguaging possible. Undoubtedly, but perhaps differently than how it has been expressed elsewhere,Role-Playing was evidence of privilege. Privilege is also localized and whilst many elements in RPGs in Colombia received considerable transformation in the process of playing, from accommodation and adoption of game terminology to translation and creativity, Role-Playing is, undoubtedly, a pleasure of a social elite (see Figure 5).

The cultural capital requirements of the game mentioned above rendered limited access to RPGs. Even with resistant practices towards the cost of materials circumvented through pirated copies and folk translations to overcome language barriers, Role-Playing remained the practice of a few middle-to-upper-class, highly educated clusters. The process of translanguaging to develop a gaming jargon only understood by the in-group was simultaneously a system of selective exclusion. As opposed to common renditions of “geek” and “nerd” culture as the social outcasts, RPGs were the realm of the more culturally savvy –an intelligentsia of sorts– in Colombia. Since the number of Role-Players remained low for most of the 1990s, it is easier to see how group members turned out. The data obtained in the small-scale survey not only highlights the education level of Role-Players, but also their mobility, since 11 of the 60 respondents of that question mention they live outside Colombia now.

Finally, bearing in mind the limitations of the survey, it was interesting to see the breath of ages of the respondents, going between 20 years old and 54 years old, with the main cluster of respondents between 37-45. Their reported age of initiation into RPGs ranged between 9-33, peaking at the age of 12 years old (7 responses) and remaining on that same peak (7 responses) between 15-17. Clearly, RPGs tend to be embraced in adolescence, well prior to academic pursuits. Although further research would be required here, it would suggest that academic studies are no prerequisite to playing RPGs. Another final aspect of the survey was that many claimed to have played in more than one named language. At least 44 claimed to have played in English (9 of whom mentioned that English was used in the forms of rulebooks or materials, rather than actual play), whereas 58 claimed to have done it in Spanish, and 2 to have done so in other – not clarified – languages.

Conclusions

Role-Playing in Colombia in the 1990s was an instance of translanguaging and cultural transduction that, also, led many into learning the written form of English. Literacy in English was certainly promoted by those playing –or wanting to play– RPGs, much in the same way that those working in computers at the time find it necessary to become competent in the language. Even if RPGs were not introduced in Colombia as a tool for language education, this seems one of their main side-effects. The addition of a variety of lexical elements into everyday speech, both from named languages or transformation and creation of new terminology in Bogotá Spanish, increased the idiolect of a whole generation of players.

Although it was beyond the scope of this article to determine all the correlations between class, cultural capital, education and RPGs in Colombia, it does provide hints and avenues that could be explored, along the lines presented by Evans. In Colombia, or at least in Bogotá, RPGs became relevant from the mid-1990s, living into the 2000s as the entertainment of an elite that received considerable attention by local media. For example, the major national Newspaper El Tiempo issued at least one news piece every year between 1997 and 2000, and then still mentioned RPG clubs in 2003. The clubs and university guilds that were developed at the time also bear witness to the impact of RPGs, and the demands in terms of cultural capital might have construed this groups as an elite, different than in the US or UK.

RPGs were constantly translated by players, particularly those taking the role of referees or Dungeon Masters, in order to bring the rules into action with the players. One such words that was adopted to mean, exclusively, a group of Role-Players was the word “party”, used with a feminine article in Spanish as “la Party” (see Figure 2). This use of an English language term to refer to the specificity of a Role-Playing group was negotiated between those who abhorred borrowed terminology and preferred the generic expression “grupo de juego” (play group) or translations to more colloquial Colombian Spanish, as in “la parranda” –quite literally a music and dance party–, and those who would be keen to use other borrowed terms as well “los runners” – in the case of Shadowrun (FASA, 1989).

Translanguaging involved, then, not only the transformation of the terminology between named languages, but a process of cultural transduction in which the elements were imbued with a given specificity of meaning when borrowed, and a marker of identity by those who used them. The shared idiolect became a label to recognise “roleros” –Role-Players– as a distinct social group. Similar to a gang, most of those who played in Trollhattan or Escrol also had nicknames, which made them even more cohesive. Cultural capital was displayed through many elements and one of them included the ability to read English to a certain level and to know the lingo.

There remains an avenue of research regarding other forms of cultural capital related to the cultural transduction or RPGs. Class and education may have a bearing to understand Role-Playing in Colombia and it may serve as a point of comparison with other countries. Translation, as the D&D Beyond forum shows, is still important when it comes to RPGs. It may also work along the same lines as dubbing; Latin American Spanish-language dubbing has become prominent in the consumption of American films in Colombia now, whereas it was not in the 1990s, when subtitling was commonplace for films and dubbing was almost exclusive for television series. Yet also more localised dubbing has also taken place in Argentina and Mexico, promoting the idea of named national languages. If the market for RPGs experiences a revival, they might follow the same path as dubbing and deliver a variety of Spanish-language versions. But so far translanguaging remains the trend.

–

Featured image 41|52 words is by Alan Madrid @Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

–

Enrique Uribe-Jongbloed is professor and researcher at the School of Social Communication and Journalism, Universidad Externado de Colombia. He has dedicated much of his life to playing table-top RPGs, reading comics and watching television, and in his academic persona, Enrique has written extensively on those three topics.

Drawings: Daniel E. Aguilar-Rodríguez (used with permission)