Cozy Aesthetics and Queer Domesticities

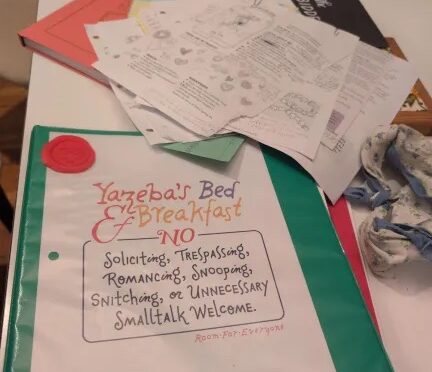

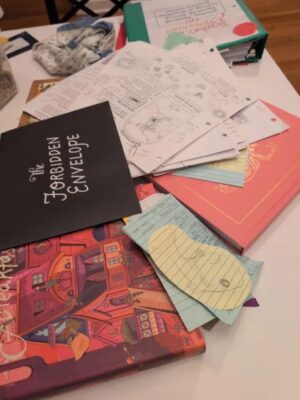

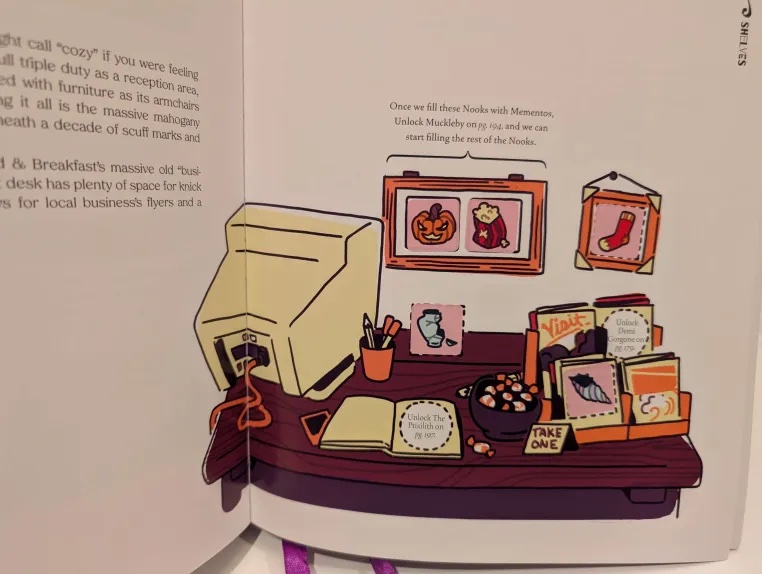

“Once upon a time, the world was cruel, and there was a witch who knew it well. And so, she sold her heart away and built a house in the woods where the world could never find her.” Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast (Possum Creek Games) by Jay Dragon and M Veselak begins with these words and presents a game focused on found family and queer domesticity in a whimsically detailed world. Each session revolves around small acts of care and chaos inside a magical, liminal home. Yazeba’s does this structurally and narratively through a legacy-style, slice-of-life system set in a magical, ever-changing house populated by a rotating cast of characters called Residents. The game owner is called “the Concierge,” who is described as a facilitator and narrator rather than a game master. The game is composed of standalone chapters that can be played in any order with mechanics that vary by chapter and often mirror the chapter’s tone. These features create a flexible, emotionally rich play experience shaped by both narrative choices and evolving game materials. Yazeba’s also encourages players to modify the physical game materials by adding marginalia as they progress through the chapters. This creates a personalized and evolving game experience that reflects the group’s collective storytelling journey.

Yazeba’s remediates, remixes, and alters the traditional mechanics of analog tabletop games. It actively encourages diverse forms of play, evocative of Boluk and Lemieux’s understanding of metagaming, the type of play that “ruptures the logic of the game, escaping the formal autonomy of both ideal rules and utopian play via those practical and material factors not immediately enclosed within the game as we know it.” There is a curated level of double awareness that is encouraged in Yazeba’s. Players are encouraged to “cheat” and unlock chapters if it feels true to their gameplay. Even the Concierge is instructed to respond a player’s contradiction of their own description of game reality with the phrase, “As you say,” and allow the player’s version to take precedence.

The game presents of vision of queered, cozy, and gameful domestic life. But does its very domesticity undercut the potential for queer play? Sparked by my own experience of playing Yazeba’s with a queer group, this article seeks to broadly interrogate how the aesthetic environments—the visual, affective, and tonal choices that shape the sensory and emotional experience of play—of the created worlds in which we play may reinforce or demand certain types of play. In this piece, I explore the tensions between cozy aesthetics and queer disruption through a close reading of Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast, drawing on both gameplay experiences and philosophical reflections. Furthermore, putting different philosophical theories of aesthetics in conversation with queer theory, I unpack the relationship between our created worlds and queer gaming to examine the importance of resisting normative expectations of identity, narrative, and success in analog play.

My central question is not whether the game is queer enough—it undoubtedly is and delightfully so, down to its mechanics and vision of home. Rather, I use Yazeba’s as a case study to interrogate a more subtle tension: how game aesthetics, particularly those of coziness and domesticity, might shape or constrain the emotional and narrative registers available to queer play. In doing so, this piece is meant to contribute to an emergent conversation in queer game studies about how tone, affect, and visual and mechanical design intersect with queerness, not only in terms of representation, but in how we play. I argue that aesthetics are not merely a backdrop, but an active force that can invite or foreclose queer chaos, conflict, and failure. This essay ultimately explores what it means to make space for unruly, dissonant queer experience within the aesthetics of comfort and care.

Queerily Home At Yazeba’s

There is no one correct way to play Yazeba’s and that is by design. Game sessions and chapters feature changing rules, with most chapters utilizing an ever-shifting primary character’s perspective. Game designer and pop culture critic Armaan Babu described Yazeba’s as

…a single place, fixed in time, a single story that can be told a thousand different ways, but growing, always growing. About community. About becoming who you have chosen to be — and having the agency to decide how fast that happens, when that happens, and how that happens. It is a game about making memories.

Gameplay focuses on cooperation, complexity, and aspects of what Edmond Y. Chang calls queergaming or gaming that “engages different grammars of play, radical play, not grounded in normative ideologies like competition, exploitation, colonization, speed, violence, rugged individualism, leveling up, and win states.”

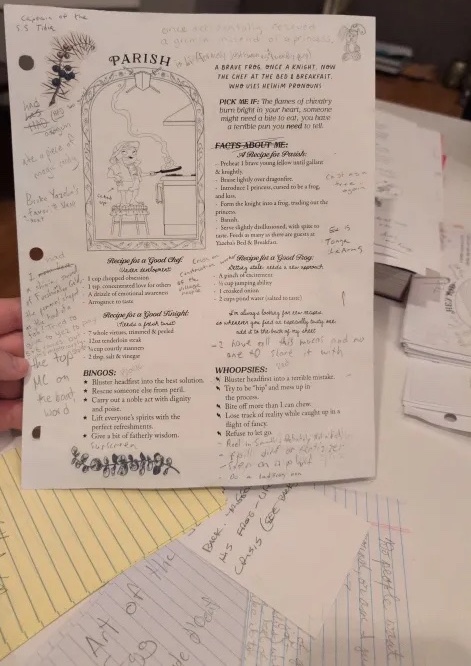

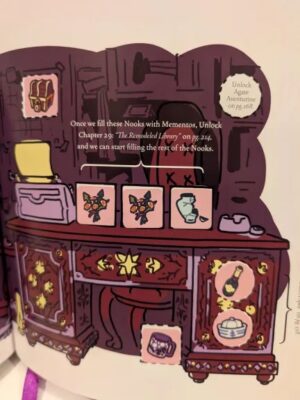

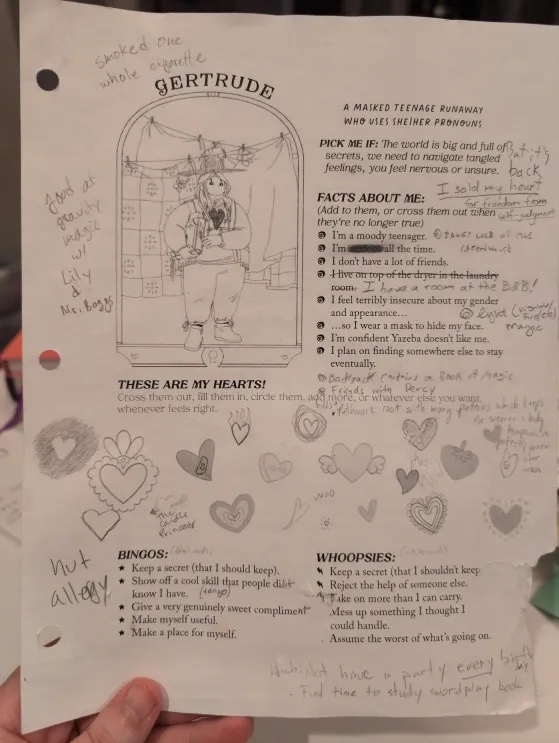

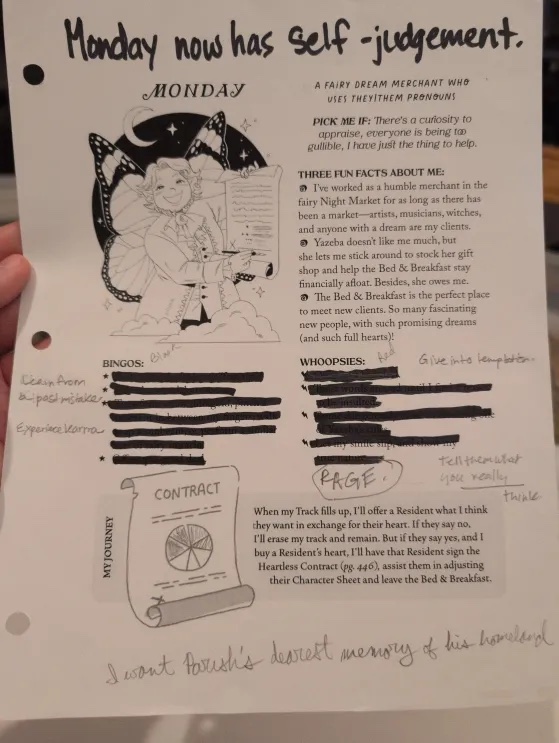

Specifically, Yazeba’s evinces what Chang calls queer remediation or the taking elements and aspects, remixing them, having them come together and interplay and interact in games in different ways. The initial characters of the residents are pre-determined misfits like Gertrude, a teenage runaway; Parish, a gallant knight transformed into a frog who now serves as the inn’s cook; Hey Kid, a mischievous devil-child; Amelie, a robotic housekeeper; and Sal, a wandering musician. The game is structured into 48 distinct chapters, each functioning as a standalone mini-game with its own unique mechanics and even different components. For example, one chapter might involve investigating a basement and have players draw playing cards from a standard deck to determine what they find. Others may involve a large group of players and involve flipping coins frantically to determine success. This episodic format allows players to explore different narratives and gameplay styles in each session.

Play of Residents is rotated through different people, all of whom have the power to alter aspects of the character’s fate, motivation, and even abilities through their choices. The Yazeba’s gamebook intentionally encourages this rotation, saying,

Whenever we play, it’s likely that we’ll swap between Residents from Chapter to Chapter. We shouldn’t worry about playing a Resident precisely the same way another player did; everyone will bring out different facets of a Resident, and all of them are equally authentic. It’s a lot of fun to share Residents, and to mix up which Characters we play. When we give a Character to someone else, it gives that Character a chance to grow in new ways.

These repercussions are passed along to the next gaming session. You might come into a session to find that someone has played Parish the week before and added notes to the character sheet.

Moreover, the game discourages a fixation on linear storytelling and continuity. Players are intentionally encouraged to reject the idea of canon. The gamebook’s section on play philosophy says, “There can be no definitive canon, and every version has its own reality and truth.” It is understood that chapters will be played out of chronological sequence and that this style will not be a barrier to player understanding.

For my first game of Yazeba’s, I was playing with a completely queer table of fellow gamers who played together many times before. We were a group of gamers who delighted in independent games, telling weird stories, and evoking emotional experiences from gameplay. I had actively had conversations about the emotional impact and transformative power of TTRPGs with many of the other players at the table. With this knowledge in mind, I approached my first session of Yazeba’s anticipating and expecting the eruptive, meta, and flirtatiously unstable play that Chang later calls “queer chaos,” an extension of queergaming, a mode of queer play that embraces exuberance, disruption, and affective messiness to resist the normative expectations of narrative and performance. Chang describes at length:

First, queer chaos is queer excess, queer exuberance. It is totally extra, totally meta. It further reimagines, even unravels, the fantasy of the magic circle, the fantasies of immersion and interactivity. Second, queer chaos is queer challenge, queer change. It is disruptive, even eruptive. It reconfigures our relationship to desire, to identity, to performance, to play. Finally, queer chaos is queer mending, queer healing, queer repair. It is disruptive, even eruptive. Queer chaos is not always legible to non-queer players and observers. It is play that subverts and appropriates the narrative of “straight” or “proper” play to center queer, BIPOC, and non-normative identities, practices, and participation. Ultimately, queer chaos is troubling play, troubling performance, and troubling the past, present, and future; it is finding new and alternative paths to the future.

Queergaming and queer chaos resists the logic of tidy narrative arcs and proper conduct. I entered my first session of Yazeba’s hungry for this chaos and excited for the potentiality for queer joy with a primarily queer table. What I got was pancakes.

The chapter our table played centered on one of the residents starting a rival bed and breakfast in the backyard so that they can eat pancakes all day long, and the panic that ensues. The session I attended essentially ended up playing out almost exactly like an episode of a TGIF sitcom from the late 1980s, complete with moments of lesson learning and emotional repair. While the game experience was lovely, at the end of it, several of the players, including myself, reflected on the vanilla, family-friendly tale we explicitly enacted. The whole thing felt cloyingly sweet, cozy, and hauntingly straight.

Whither Queer Chaos: An Aesthetic Problem?

Despite a queer-identified group of players playing a very queer game, the story we collectively created felt cloyingly heteronormative. Players began joking that they had been typecast into familiar roles: the sitcom dad, the zany (vampire) aunt, the precocious child. While Yazeba’s promotes a vision of inclusive and harmonious domestic life, that togetherness as it manifested in our session may have inadvertently aligned with traditional ideas of domesticity. This was a vision of home that embraced stability and harmony, potentially at the expense of acknowledging and embracing and fluidity and complexity that often surrounds and queer identities, stories and experiences. Players articulated not wanting to disturb the setting of Yazeba’s itself.

I wonder if the overall aesthetic of the game show us a desire for a domestic vision that may truncate the experience of queering play? Or, what kind of home is Yazeba’s, and what kinds of queer play and politics does it enable or inhibit? Stephen Vider reminds us that “home has been a crucial though contradictory space in LGBTQ life and politics—a site of constraint and a site of self-expression, a site of secrecy and a site of recognition.” While the game never explicitly instructed us to follow these harmonious and peaceable paths, the aesthetic cues (with twee illustrations, language of “whoopsies” and “bingos” in lieu of success or failures, et cetera) seemed to pull us toward domestic harmony that left little space for queer volatility. Yazeba’s also had an element of almost chasteness that made the possibility of more erotic play seem out of the question. Upon further reflection, I believe my gaming table was not pushed towards good wholesome play by mechanics alone, but by something about the cozy aesthetic of the game that also seemed to domesticate us. The games seemed to exert a gravitational pull toward suburbanized family values and emotional stasis. This is not a flaw of Yazeba’s design, but a reminder that aesthetic form shapes affective response. Our gameplay was not merely guided by mechanics, but domesticated by the game’s aesthetic frame. The experience raised even deeper questions: Can cozy aesthetics (however well-intentioned) pacify queer potential? Can a world designed to feel safe still hold space for the risk, rupture, and excess that queerness sometimes demands?

Cozy games, which are notoriously difficult to define and range widely across genres, are often described as being defined by their aesthetic goals, and not their topics or mechanics. Cozy aesthetics typically evoke feelings of warmth, harmony, and emotional safety, often drawing from visual and narrative cues rooted in domesticity, nostalgia, and homeyness. The session showcased the aesthetic demands that were also being placed upon player gameplay.

The experience we had at Yazeba’s points to the impact of aesthetics on our lived reality and behavior. Aesthetics refers to the study of perception, taste, and the nature of beauty and artistic experience. It examines how people are moved by forms and sensations, and how style and design influence one’s understanding of the world. But aesthetics is not just about beauty or design—it is inherently ideological and political, shaping what is seen as valuable, acceptable, or possible within a given cultural frame. Terry Eagleton vividly describe aesthetics as “nothing less than the whole of our sensate life—the business of affections and aversions, of how the world strikes the body on its sensory surfaces, of what takes root in the guts and the gaze.” Aesthetic conversations in game studies have often focused player experience and design elements, emphasizing how visual style, sound, and mechanics produce affective responses and shape gameplay. Scholars like Jesper Juul and Miguel Sicart highlight how aesthetics are deeply tied to interactivity, with Sicart arguing that games are “ethically and aesthetically expressive systems” that communicate values through play. Thinking aesthetically involves understanding the meanings and values embedded in pleasure and design. This extends to Juul’s idea of “ludic aesthetics,” which even considers the pleasure derived from the rules and gameplay itself. Ludic aesthetics refer not just to how a game looks or sounds but to the aesthetic experience produced by its rules, structure, and mechanics. In cozy games like Yazeba’s, the rules themselves may also be gentle, forgiving, and collaborative, but these qualities also produce a certain kind of affective tone.

When ludic aesthetics emphasize harmony or comfort, they can predispose players toward cooperative, low-stakes narratives, reinforcing emotional safety at the expense of narrative risk or rupture. Through ludic aesthetics, rules can actively shape the affective palette of a game world and help determine what kinds of stories feel appropriate or playable. This approach is notably pragmatic, attending to how aesthetic choices influence player behavior and immersion. On the surface, this could seem to solve the predicament of pancakes that my fellow players and I experienced. However, Yazeba’s should not receive the blame for our gameplay’s descent into heteronormitive play so quickly.

While in game studies, aesthetics are often treated as structuring player experience through things like game feel and affective affordances, in the philosophical tradition, aesthetics also examines personal judgment and reflection spurred by what we experience through our senses. Where game studies often treat aesthetics as instrumental to engagement, philosophy interrogates aesthetics as a mode of critical reflection potentially separate from utility. Instead of foregrounding what aesthetics do, philosophy often asks what aesthetics mean and how aesthetic experience relates to truth, subjectivity, or the social world. These are not separate frameworks, but incomplete when left apart. If game studies sometimes fails to account for the political and ideological weight of aesthetic form, then queer game studies must take up the task of integrating both approaches.

Game aesthetics are never neutral: they encode assumptions about the world, the self, and what kinds of futures are imaginable. This is especially urgent in cozy games like Yazeba’s, where the warmth of design may unintentionally narrow the field of queer play. This tension invites further interrogation when games adopt aesthetic frameworks, like “coziness,” that might carry cultural and ideological weight. Aesthetic categories like “coziness,” are treated as innocuous design choices, but carry embedded ideological assumptions. What game studies might analyze in terms of affect and design, philosophical aesthetics might interrogate for ideological content or complicity in systems of commodified comfort. Taking several philosophical lenses to the gaming experience I had playing Yazeba’s can help bridge these perspectives and reveal how aesthetic categories are not merely stylistic, but epistemological and political, shaping not only how we play, but how we think, feel, and relate to the world. This works in tandem with Jason Bryant’s understanding that when a home is queer, the category of the domestic is scrambled and now expanded to be both a simple place of shelter and the feelings of belonging.

To fully understand the ideological force of cozy aesthetics and their impact on queer play, we must examine how aesthetic forms mediate power, comfort, and identity. Immanuel Kant, Gaston Bachelard, and Theodor Adorno offer distinct but overlapping insights into how aesthetic experiences shape not only perception, but the political and affective boundaries of what feels possible. Read together, they reveal how cozy games like Yazeba’s might unintentionally limit queer chaos by aestheticizing harmony, suppressing discomfort, and channeling desire into familiar, culturally sanctioned forms.

Beautiful or Sublime?: Yazeba’s Through A Kantian Aesthetic Lens

Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgment offers a foundational distinction between the beautiful and the sublime that further expands the aesthetic orientation and interpretation of Yazeba’s. In his seminal work on the philosophy of aesthetics, Kant discusses the beautiful and the sublime. These aesthetic poles offer a lens to critique cozy play as harmonizing and safe, in contrast to the overwhelming intensity of queer chaos. For Kant, the beautiful is characterized by harmony and proportion (e.g. a perfectly symmetrical daisy) and had “purposiveness without purpose.” Beautiful things express purposiveness because they have a structure or form that our minds recognize. But they just exist and do need to be utilized like tools to have worth. They are beautiful, and that is all they need to be.

In many ways, Yazeba’s, game world has purposiveness without purpose. Its stories are emotionally rich, its game book lovingly designed, and it encourages growth and connection, not the “winning” or completing a quest. The game creates a world that feels meaningful, structured, and pleasing without being subordinated to a goal. The gamebook’s reminder that there is no canon timeline in gameplay echoes this saying, “We can replay the same Chapter again and again without worrying about what happened the last time, or which playthrough was the ‘real’ playthrough.” It is an aesthetic experience in Kant’s sense—disinterested, harmonious, and self-contained.

However, this beauty may unintentionally suppress the unruly, uncanny, or painful aspects of queer experience that fall within the aesthetic register of the sublime. For Kant, the sublime refers to objects or experiences that are overwhelming, vast, or the sort of awe that borders on discomfort. This aesthetic leaves room for the importance of things that overwhelm us, not just what pleases us. Especially within the framework of the queer experience, the need to hold space for the overwhelming is essential to not erasing the history or experience of the community. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet emphasizes the perennial nature of instability, opacity, and affective intensity of queer experience. Queerness, for Sedgwick, is not always joyful. It is often sad, paranoid, or even ambivalent.

Interestingly, a deeper examination of Yazeba’s game book reveals space for the sublime. The book explains that many of the Chapters (scenarios for sessions of play) have tags. These tags serve to indicate to the Concierge the tone of the chapters and include frantic, pensive, eerie, and heavy. The heavy tag explicitly says “This indicates the Chapter is heavier in tone than usual, dealing more explicitly with real-life themes, oppression, danger, or trauma.” This points to clear space within Yazeba’s for the uncozy and often frightening aspects of the sublime.

Cozy and the Aesthetic Effect of Home: Yazeba’s through Bachelard

If aesthetic experience shapes our epistemologies and politics, then attending to the emotional textures of games like Yazeba’s reveals more than just player preferences. Yazeba’s a definition of home is a queer, affective sanctuary. It is a space where care and co-created narrative replace violent conflict and rejection. It reimagines domesticity not through binary heteronormative obligation, but typically through elective kinship, gentle rituals, and player-driven imagination. A robot is a housekeeper. A former knight does the dishes.

To understand this affective tilt toward the harmonious and its impact, we must examine the philosophical and aesthetic roots of cozy domesticity. Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space explores the phenomenology of the home not merely as a physical shelter, but as a site of reverie, imagination, and a “topography of our intimate being.” He asserts that the homes should be understood as also serving as a psychic state that encourages intimacy. Yazeba’s echoes this vision, creating a space where chosen family is fostered and imagination is cultivated precisely through the emphasis on player agency and leaning into the feeling of something as being reflective of truth. The bed-and-breakfast becomes a sanctuary for chosen family, a queer utopia grounded in shared meals, seasonal celebrations, and gentle growth.

Yet Bachelard also acknowledges that domestic spaces can conceal as much as they reveal and cautions that domestic spaces can trap us. They are repositories of secrets, silences, and emotional stasis reinforced by both broader external expectations and personal ones. The very structures that nurture can also enclose. The same spaces that nurture fantasy and care can become sites of stagnation or even melancholy when it becomes very difficult to leave the safety of a home environment for places of intense anxiety or struggle.

This ambivalence becomes crucial in reading cozy aesthetics critically. Cozy environments can often lead those within them to seek further safety away from risk rather than using the safety to experiment. Warm environments like Yazeba’s might encourage a player to replicate the comfort food narratives they were raised on rather than experiment with bolder and more chaotic stories. For instance, instead of embracing a storyline where a character never finds reconciliation with their estranged parent, a player might steer the plot toward healing and reunion because it “feels right.” Rather than exploring characters who reject traditional roles, players might default to tales of belonging, forgiveness, or cheerful domestic integration. They might avoid conflict-heavy scenes, skip over interpersonal messiness, or resolve narrative tension quickly to preserve group harmony. In this way, the safety of cozy aesthetics can foster a kind of narrative risk-aversion, encouraging repetition of sanitized storylines over exploration of queer, contradictory, or emotionally difficult possibilities. Bachelard helps us see how domestic space is both intimate and entrapping and how cozy aesthetics can shelter queer play, but also contain it.

No Room for Suffering: Adorno and the Cost of Aesthetic Comfort

Yazeba’s does not reinforce heteronormativity, but players’ commitment to the game’s cozy aesthetic may nonetheless replicate a similarly limiting logic. In other words, while the game’s design explicitly affirms queerness, its tonal emphasis can inadvertently pacify the more volatile, disruptive, or politically potent dimensions of queer experience. At our table, this manifested not through the game’s mechanics, but through the stories we chose to tell—ones that leaned into nostalgic comfort and away from conflict and rage.

The work of Theodor Adorno is helpful in illuminating some of the subtle ways in which our table may have been drawn towards a peaceable and overly harmonious way of playing. Theodor Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory warns that harmonious or reconciled aesthetic experiences risk reproducing the pacifying tendencies of what he famously called the culture industry. Adorno, a German-Jewish philosopher and critical theorist, fled Nazi Germany and developed much of his thought in exile. His historical context profoundly shaped his pessimism about mass culture. Adorno’s aesthetic theory insists that true art must resist easy pleasure, clarity, or emotional reconciliation. “Art is the social antithesis of society,” he writes, “not directly deducible from it.” That is, genuine artworks remain unfinished, difficult, and even contradictory. They are meant to allow suffering and conflict to be witnessed rather than soothe it away.

Adorno’s suspicion of aesthetic reconciliation helps articulate the danger of coziness as emotional pacification, when softness becomes complicity. For Adorno, the danger of aesthetic experiences that offer comfort without critique is that they risk becoming complicit with dominant ideologies. Such works may reproduce the false sense of wholeness and emotional equilibrium that capitalism sells as happiness. Yazeba’s presented our table with a colorful home, but we made the move to fill it with a saccharine TGIF narrative sold to us in our childhood that sidestepped conflict and negativity.

This aesthetic drift aligns with Lisa Duggan’s concept of “the new homonormativity” in The Twilight of Equality?, where queer inclusion is predicated on neoliberal values of privacy, consumption, and domesticity. Duggan describes this politics as one that “does not contest dominant heteronormative assumptions and institutions, but upholds and sustains them.” While Yazeba’s itself resists overt heteronormative structures, the ways players embrace its coziness can subtly reinscribe familiar norms under the guise of comfort. It may celebrate queerness insofar as it is soft, kind, and found family-oriented, while leaving less space for queer rage and excess.

Our game was not the fault of Yazeba’s pastel palette or the language of Bingos and Whoopsies, but rather, a reminder that sometimes the calls are just coming from inside our own heteronormatized houses. My gaming table and I were not critiquing our own kinds of internalized desires and instead falling into aesthetic funnels that Adorno reminded us can be tricks or traps. Adorno reminds us to be careful about the ways in which we may mindlessly replicate culture we do not believe when we surrender to aesthetic experiences.

Queer Aesthetics, Queer Failure, and Reparative Play

While Adorno and Duggan offer incisive critiques of how aesthetic comfort can neutralize political potential, their frameworks also point toward a deeper question: what might queer aesthetics look like when they refuse reconciliation? If we resist being pacified by beauty, harmony, or homonormativity, where can we turn to find aesthetic models that affirm queer volatility, contradiction, and risk? This brings us to the work of José Esteban Muñoz and Jack Halberstam, who refuse to frame queerness solely through the lens of recognition or safety. Instead, they offer alternative visions of queerness grounded in disidentification and failure. These are frameworks that may help reclaim queer chaos even within aesthetics that would prefer to keep us docile.

José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of disidentification, from Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, involves negotiating and resisting dominant norms. Disidentification is a strategy used by marginalized individuals to navigate and transform dominant cultural frameworks. Yazeba’s portrayal of found family and queer domesticity can be seen as a form of disidentification, creating a space for alternative identities and relationships. By presenting a vision of inclusive, cooperative domestic life, Yazeba’s challenges traditional notions of family and home. However, Muñoz’s concept also invites us to consider how these spaces can be both transformative and constraining. In these queer spaces, we neither need to reject nor accept norms. His work asks us not only to resist reconciliation, but to interrogate how normativity co-opts even queer performance, and how marginalized subjects navigate such terrain tactically.

While Muñoz’s concept of disidentification reveals how queers of color might tactically inhabit and subvert dominant cultural scripts, Jack Halberstam offers a different, though complementary, pathway toward resistance: failure. Where Muñoz locates political agency in the performance of navigating and transforming existing norms, Halberstam turns to the refusal to participate in them altogether. The Queer Art of Failure celebrates getting it wrong and opting out not as a loss, but as a creative undoing of systems that demand coherence, productivity, and success.

Halberstam’s work encourages embracing failure as a form of resistance and a way to create alternative modes of being and knowing. This perspective aligns with the game’s subversion of traditional success narratives and highlights the potential for queer art and culture to offer alternative visions. Failure is an active resistance if we find ourselves being moved in a particular direction that is inauthentic, or worse, mired in the success-driven logic of capitalism and heteronormativity. In games, this translates to rejecting the pressure to “win” or conform to traditional narrative arcs. If a game tries to force you to play in a particular way that feels constraining or heteronomative, queer resistance might be intentional failure.

Failure as action against the goal of an oppressive game can produce alternative ways of being or knowing. The concept of “playing to lose” is a form of embracing queer failure in games. This idea is gaining more traction with game designers (especially horror games) and game scholars alike and invites players to understand that their character’s inevitable doom can invite creative play choices and ways of being. Failure then transforms into a site of narrative richness. The goal of the playing the game shifts from control to exploration of the uncanny, the overwhelming, and the emotionally fraught. Eric Stein argues that intentional failure allows players to access vulnerability, intimacy, and atmosphere.

In the context of Yazeba’s, this principle becomes especially resonant. While the game mechanics don’t necessarily enforce a “winning” trajectory, the aesthetic tone can exert a normative pull toward tidy, conflict-free narratives. Yet queer players can choose to subvert this, not by rejecting the game, but by playing against the grain. Queer failure in Yazeba’s might look like intentionally fracturing harmony, leaning into emotional mess, or enacting chaotic disruption. I played that same chapter of Yazeba’s with a different group weeks later and had a wildly different experience. In it, Yazeba the witch barely managed to come out of her bedroom because she was depressed. She chain-smoked Virginia Slims cigarettes and just impassively watched the pancake war, and finally gave Hey Kid the ultimatum of potentially needing to leave the B&B. It was tense, chaotic, mournful, and deeply satisfying. The difference was not in the mechanics or aesthetics of the game—we were still playing Yazeba’s. It was in the players’ willingness to lean into disruption, to follow the thread of queer chaos rather than overwrite it with a familiar template from a homogenized upbringing.

However, it is important to acknowledge that failure is not a neutral strategy. Critics have pointed out that Halberstam’s vision of queer failure often relies on a subject position unburdened by the risks that come with structural oppression. Muñoz’s framework of disidentification helps illuminate anchor Halberstram’s failure by insisting that any exploration of queer aesthetics must account for whose bodies, risks, and desires are at stake. Disidentification is not about aesthetic rebellion alone, but survival and improvisation shaped by constraint. Halberstam’s queer failure offers useful tools, but they require careful contextualization to avoid flattening differences in privilege and access.

Framing of failure as solely subversive or liberatory risks universalizing what is, in fact, a highly contingent and racialized experience. As Aaron Trammell argues in Repairing Play: A Black Phenomenology, traditional play theory has long ignored the painful, coercive, and racialized aspects of play. When play is defined solely through pleasure or refusal, it excludes BIPOC experiences of play as surveillance, discipline, or even torturous. Dominant definitions of play too often rely on assumptions of voluntariness and pleasure that erase how marginalized communities and especially BIPOC players are frequently subjected to play as surveillance or coercion. In this context, queer chaos cannot be disentangled from questions of racialized power: not all players approach the table with equal safety to disrupt or improvise. Some are always already positioned as spectacle, as risk, or as the ones being “played” with.

This insight deeply complicates Halberstam’s queer failure. What looks like playful refusal from one positionality might resemble dangerous vulnerability from another. Trammell’s critique reminds us that not all queer bodies are granted the freedom to fail safely. It is Muñoz’s disidentification, grounded in the friction and navigation of hostile structures that may offer a more materially situated path for queer aesthetics. Disidentification is not just symbolic, it is survival.

This theoretical framing invites us to return to the table not just as a site of play, but as a site of aesthetic and political decision-making. The dynamics Trammell and Muñoz describe are not abstract; they unfold in real time, in real bodies, through real choices. Nowhere was this clearer than in the contrast between two of my own play sessions. Yazeba’s was never forcing my first table and I into reenacting wholesome elements and understandings of domesticity taken from other rigidly straight media. We just leaned into those old scripts, where my second table leaned out and embraced chaotic disidentification and aesthetic failure. If queer chaos unsettles narrative norms, in Yazeba’s or other games whose initial aesthetic may be more domestic, this can mean rejecting the pull toward coziness, not because softness is inherently bad, but because unquestioned comfort can pacify.

Making Room for Queer Chaos

Is there room for queer chaos at Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast? Of course. But rather than antithetically trying to find the “perfect” platform to enact queer chaos (which feel a bit like planning to be spontaneous), I argue that queer chaos makes room within us. The task, then, is not to ensure that every session becomes an aesthetic revolt, but to remain attuned to the contradictions and desires that animate our play, even when they are messy, nostalgic, or simply “too queer.” I will close by advocating for two practical approaches to make room for chaos within ourselves as players – attuning to our desires and practicing domesticity without domestication.

This attentiveness begins with the seemingly simple, but profoundly political practice of listening to desire. That first pancake session was not without merit. Yes, it echoed heteronormative sitcom tropes. But it was also joyful, funny, full of care, and a lot of fun. Chang’s conceptualization of queer chaos offers a helpful illumination on this experiences. To reiterate, queer chaos is play “that subverts and appropriates the narrative of ‘straight’ or ‘proper’ play to center queer, BIPOC, and non-normative identities, practices, and participation.” Although the table was playing out the straight-laced nuclear family stereotypes of a TGIF episode, our desires as a queer table was to participate and weave the narrative of wholesomeness through our own experience. This was a table of players whose queerness had led to experiences of tension with blood family and alienation from communities of origin. I found myself, a disaffected Catholic, suggesting that our characters all go to church together and have pancakes after every week to prevent conflict in the future, echoing my own family’s rituals of pizza after 5pm Saturday mass growing up. While tongue-in-cheek in the moment and intended to fit the narrative of sitcom we were weaving, I can see in my actions my own desire for queer reclamation of ritual that is no longer available to me.

As queer players, we are often caught between the need to resist the scripts imposed on us and the desire to remix them into something livable. Desire, in this sense, is not a pure or primal truth, but a site of negotiation between memory and possibility, comfort and disruption. Trammell’s reparative approach to play urges us to attend to how grief, survival, and inherited pain shape the affective field of gameplay. For some players, desire is already inflected with violence and play may be less about subversion than endurance, less about fun than finding fragments of freedom within deeply constrained systems. This reframes desire in games not as a spontaneous outpouring of inner truth, but as something cultivated within systems.

In practical terms, players can cultivate space for queer chaos by setting tone at the table and explicitly naming if they have a willingness to explore tension, failure, or mess. Trammell urges us to reconsider whose play is centered and whose pain is obscured. “Repairing play,” he writes, “means rethinking how we understand questions of consent…recognizing how one person’s play is another’s prison.” This could include a GM checking in about group tone when sessions feel overly saccharine, or asking players to rotate characters mid-session to destabilize fixed roles. The second group’s willingness to lean into depressive stagnation, emotional mess, and ambiguous intimacy acknowledged that coziness can erase the real costs of care and comfort. These practices do not reject cozy games; they refuse to let coziness become a cage that keeps a table of player from following a desire together. Vider frames domestic norms as “a script: socially determined yet individually enacted; predetermined yet open to interpretation, improvisation, revision, and failure.” Just as gender is constituted through stylized repetition, Yazeba’s players are invited to rehearse domestic scripts, but they may also rewrite them. Cozy, in this view, is both opportunity and trap. The invitation of queer chaos is not to reject a desire for sweetness, softness, or structure outright in games, but to ask whose scripts and pleasure we are centering and why.

To borrow from Kant’s idea of purposiveness without purpose, we need to embrace domesticity without domestication. That is, to engage in narratives of care and home without being captured by their normative constraints. This might mean noticing when we default to harmony because it feels easier than rupture or interruption of a table dynamic. It might mean letting our characters be selfish, chaotic, or unresolved or letting a session end in silence rather than closure if you are GMing a game. In Yazeba’s, it might mean choosing the chapter tagged heavy when your impulse is to avoid it. Queer domesticity is not about perfect comfort, but the creation of a space of safety for discovery. Game designers, too, can help un-domesticate domesticity. This does not mean abandoning gentleness, but expanding its emotional range. This may include intentional mechanics that reward ambiguity or interruption.

What does domesticity without domestication look like, especially for queer players whose relationships to “home” are often complex, haunted, or ambivalent? One possibility lies in third spaces: liminal, collective environments that resist ownership, obligation, and permanence. Queer games and gaming table can function as such a space, not because it replicates the nuclear family or offers a fixed sanctuary, but because it allows for flux, difference, and refusal. In Yazeba’s, no one owns the narrative. Characters are shared. Chapters are shuffled. Continuity is optional. This design offers a model for a kind of queer domesticity that is less about containment than about movement. Vider’s vison of a queerer home in The Queerness of Home included “recognizing the material, psychological, and cultural meanings embedded in the everyday practice of homemaking—not to deny or reify its power and primacy, but to question and expand its limits.” It is a home that doesn’t trap us in inherited roles. A space of care that does not calcify into conformity. If every session is a return and a departure, then what we build together is not a house in the woods to hide from the world, but a door that swings open and shut freely, never locked, never owned.

In that sense, the queer tabletop becomes a testing ground for what José Esteban Muñoz called queer utopia, a glimpse of possibility that doesn’t require arrival or perfection. When we allow Yazeba’s and even D&D to be strange, sublime, heavy, and even absurd, we do more than subvert heteronormative aesthetics. We practice queer world-building. Chang’s work on queer chaos is an invitation to allow space in how we define queer play. Reflecting on this Chang says,

Given that games are designed experiences, structures of feelings, and systems of power, I am thinking about ways to extend my definition of queergaming to imagine what it means to play when the rules and roles of respectable play are ignored, repurposed, even exploded. It is time to update the definition, to add to the list, and to try different add-ons and expansions. In other words, how might queergaming surrender to queer chaos, queer excess, and disaster queerness.

In the surrender to queer chaos, we can build and rebuild a shared space of queer play that no one owns, but everyone sustains. That might be the truest form of queer home.

–

Featured image from Lisa Hartman and friends’ Yazeba’s Bed and Breakfast game materials. Used with permission.

–

Abstract: This article explores the aesthetic and philosophical tensions embedded in Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast, a narrative tabletop role-playing game that centers on queer domesticity, found family, and emotional intimacy. Drawing from a personal gameplay experience and broader theoretical frameworks, the essay interrogates how the game’s cozy aesthetic might both invite and constrain queer play. While Yazeba’s champions narrative openness and queergaming practices such as character sharing and metagaming, some of its visual and tonal cues may inadvertently domesticate queerness into normative forms of comfort and stability. Through the lens of aesthetic philosophy and queer theory, the article engages the works of Bachelard, Kant, Adorno, Muñoz, and Halberstam to question whether comfort-centered design can flatten the volatile, messy, and dissonant dimensions of queer experience.

Keywords: TTRPG, Yazeba’s, aesthetics, disidentification, cozy games, queergaming, queer failure, queer chaos

–

Susan Haarman is Associate Director at Loyola University Chicago’s Center for Engaged Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship where she facilitates faculty development and the university’s service-learning program. She holds a PhD in Cultural and Educational Policy Studies and is also a licensed therapist. Dr. Haarman’s interdisciplinary research focuses on the intersections of social justice education and community-based learning, but her heart belongs to her work on John Dewey’s educational and democratic philosophy and the capacity of tabletop role-playing games as formative tools for civic identity and imagination. She has been running a three-year campaign that takes inspiration from the history of Chicago, which is always more fantastical than fiction.