Introduction

Loneliness is considered a significant societal problem in modern western society. Even though Denmark is regarded as one of the happiest nations in the world, a large part of the population often feels lonely or socially isolated. In a national health self-survey, 18.3% of young Danish men and 26.3 % of women considered themselves long-term lonely. Volunteer organizations such as Ventilen, Husrum and SIND Ungdom are trying to help form communities for lonely young adults to meet together with peers and volunteers. Unfortunately, due to a lack of resources and volunteers, it can be challenging for the organizations to reach everyone attending and to help them form sustainable social interactions outside of the organizations’ meeting spaces. This paper is based on a single design case study, which examines how to use a leisure card game (transformed into a social game) to help attendees make meaningful social interactions when no volunteers are available to shape the encounter.

Research Question

To investigate if social games may have an impact on how social interactions are shaped and enacted, this study addressed the following research questions: How can a leisure game be “hacked” so it acts as a social catalyst when played? What knowledge about loneliness is gained from the method?

The resulting paper contributes knowledge about how social games can be used in context to combat loneliness among young adults.

Theoretical Outline

Loneliness

Loneliness often occurs when there is a social discrepancy between what the subject expects and what is realized in the actual situation they find themselves in. Studies have shown that long-term loneliness has a negative impact on the lonely person’s way of communicating and interacting in social encounters, which can reinforce the feeling of loneliness or the feeling of “being wrong” in the sense that the long-term lonely person has lost the ability to understand social norms in different social settings that are a part of their everyday life.

Social Design

“Social Design” refers to a design process focusing on including different stakeholders to make a change for various vulnerable members of society. All of us can, in our lifespan, find ourselves in such a vulnerable position, either due to our own illness or illness of a close relative.

The design principles for involving stakeholders have historic roots in the Scandinavian participatory design tradition. Social design is using participatory design methods (also called Co-design) to involve communities to take an active part in the design process. In this study, the young adults and the volunteers of the organization whom we have been working with are the social design participants, as we can imagine they would use the game in their practice in the organization. The study is trying to make a social change in the way that these organizations work, by creating spaces and situations that encourage meaningful social interaction for the lonely young adults.

“Magic” Spaces

Huizinga first introduced the concept of “the magic circle” in Homo Ludens. Huizinga described how we as humans transcend into a magic space when we interact through playful activities, e.g. games and theatre, among others. In the magic circle, the cultural setting that we normally are a part of temporally dissolves and vanishes into a new world where society’s normal conventions and rules are not applied. Instead, the play and the playful human are creating a world of their own for the time playing or enacting in a specific context. For his study, Huizinga investigated a playground, a courthouse, and different religious places, and identified that the three domains had a similar effect on how the humans were behaving at the different places.

Salen and Zimmerman later defined the magic circle when playing games as a way of crossing over a border from the real world and then engaging in a new temporal reality that, similar to Huizinga’s construction, does not exist in the current form. Salen and Zimmerman’s work introduced a framework for creating and analyzing games through the magic circle concept.

The magic circle lies in the foundation of the playful encounters that happen inside the circle, and then when the encounter is finished learnings might expand into the participant’s social life as a consequence of the encounter. This phenomenon has been described as a breach of the magic circle where the game world and the real world blend and can result in a new experience of the played game.

Game Frameworks

Games can be used in various settings and for multiple purposes and research interests: A game can have the purpose to be designed for leisure. When designed for a specific educational context, it is often referred to as a “serious game.” Specific digital educational games might focus on environmental problems, training of health professionals, or simply teaching useful skills. A serious game can also function as an ethnographic tool for understanding the world through the lens of the player.

It can be argued that all multiplayer games have a social element when played, since these games must be played with known or unknown peers. However, in the different categories listed above, the social aspect isn’t the primary reason for playing, but rather a derived part of playing together. Social games are used to intentionally create social change in different contexts, and when designed according to the mantra of social design, they involve those who are being designed for.

As Markussen and Knutz argue:

Social games, on the other hand, entail a broader conception informed not only by the aforementioned disciplines, but also by social design, sociology, play theory, and aesthetics. The primary objective of social games is neither learning (as in serious games) nor health improvement (as in health games), but to alter or ultimately strengthen the social relation between people playing the game. This means that social development at an interpersonal level is the central game goal. There is a need for a nuanced understanding of how gaming and play may be constitutive of social relations outside the game play.

As they state, a game can be designed to foster and shape interpersonal connection and communication as the primary goal of the gaming session, letting the participants reflect upon their identity as the game evolves.

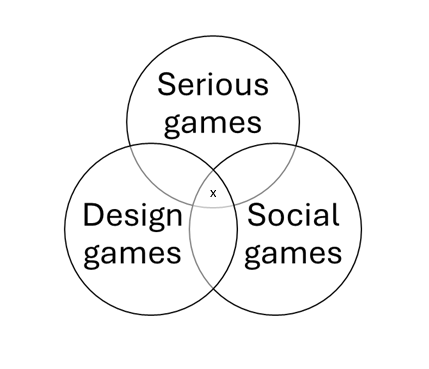

It is worth considering that all the types of games mentioned above from time to time interfere and overlap with different domains. The design of a social game has the goal to evoke social change but can intentionally or unintentionally have multiple purposes. The Hacked UNO game designed for this case has the intended purpose to evoke social change in the organization while acting as a “volunteer.” But as I will argue later, the ripple effect from the game also causes the game to overlap into the other categories shown in Figure 1, as it could also be analytically approached as an ethnographic design game or as a serious game.

A Small Stories Analytical Approach for Understanding Interactions

To understand how games can help shape conversation in interaction, I use an analytical approach that frames “small stories” as narratives that can reveal how social interaction is occurring. De Fina and Georgeakopoulos argue in their 2008 article that narrative analysis had historically been used to analyze interviews where the participant provides reflections on past events by presenting narratives constructed with a beginning, a middle, and an ending. That is, they tell stories that have already unfolded. The framework from De Fina and Georgakopoulou shifts this temporal aspect of the narrative analysis approach, as they argue that narratives also appear in the present in interactions, with the same recognizable structure, which Labov and Waletsky define as a beginning, a middle, and an ending.

Before De Fina and Georgakopoulou’s special issue of text and talk, Michael Bamberg also argued that narrative analysis could be used to see what happens in in-situ social practices, not only in the biographically oriented interview. Bamberg shifted focus from the long, completed narrative to in-situ small stories taking place in everyday interactions, described as a form of drama play with different actors and plots. Bamberg showed that small stories that happen in a situated interactional setting, do not always have all three beginning, middle, and ending (BME) elements of a traditional narrative, as described by Labov and Waletsky.

The use of BME as an approach to narrative analysis frames a narrative as a closed-ended setting or situation where there isn’t a BME. The small story that occurs in interaction is much more open-ended and without the linear temporality of storytelling. It is more emergent in the interaction or as Bamberg et al. describe it: “More than that, as we will show in our analysis, we stay alert to the fleeting moments of a ‘narrative orientation’ in interactions, for example, starting a story and not finishing it, signalling that there is a story to tell but not telling it.” I will show in my analysis how some in-situ small stories can be open-ended, based on the theoretical foundation from Bamberg and Georgakopoulou. With this case study, I explore how narratives can shift form from text to practices, and how games might help shape conversation in interaction. The small story analysis will be used to explore the interaction within the game.

Case Study: The Design of a Game for Lonely Young Adults

This case study is a part of a comprehensive study that aims to use design methods to gain knowledge about how loneliness is shown in situated social praxis. The research aim/question for this study can be divided into two areas: a) how leisure games can be redesigned to act as social catalysts, and b) how this social design method can generate knowledge about loneliness.

Case context

As a part of the larger study, preliminary video observations and field notes were conducted to learn more about loneliness and the efforts to remedy the condition. A volunteer organization called Husrum, which is based in different cities in Jutland, Denmark, agreed to engage in the research project. In order to conduct the research, a number of observations studies were planned.

During my visits to the organization, I noticed some interesting challenges that were occurring while I was observing what was going on between the participants, when there was no volunteers around.

As I was going through my field notes and recordings, four challenges were generally occurring in my material:

- The young adults did not know what each other’s names were.

- Participants were sitting sedated in one place for almost the entire night, and only did a little talking with those who were sat beside them.

- There was minimum initiation of conversation and getting to know each other.

- They restricted themselves from asking for small favors like passing the water when they were thirsty, and instead waited to reach for it or went to fill a glass from the tap.

Compared to what happens when a volunteer was joining a group, the challenges as described above, was not occurring much. There was therefore a challenge where there was no volunteer around to initiate different kinds of interactions.

The findings from the fieldwork made me curious to investigate if it was possible to intervene with the use of a playful encounter to see if it could be a useful way for lonely young adults to engage with one another socially.

In my field studies, some of the activities that the organization arranged were game nights, where they played different leisurely, fun tabletop games that ranged from strategic complex games to fast action games like UNO. I therefore decided to design a hacked version of UNO, to see if I could somehow transform the fast-paced leisure game into a social game.

Hacking UNO

UNO is a fast-paced game which is won by getting rid of your cards as fast as possible. The game is one which many have played at some point in their life. An UNO deck consists of 104 cards divided into different sub-groups. The largest card sub-group, totaling 72 cards, is the regular number cards, with numbers from zero to nine in the colors red, yellow, green, and blue. I decided not to “hack” or change the card attributes in this group, in order to not slow down or change game play too much.

The remaining cards have special attributes that introduce game mechanics to change some dynamics in the game, like switching turn-taking from clockwise to counterclockwise. In Hacked UNO, I added a task that the player should solve before the card’s original game mechanic is triggered. These tasks are meant to initiate social interaction, based on the challenges identified in the initial fieldwork. The game was co-designed with the users and volunteers in the organization Husrum, as they filled out cards with different challenges that they had. This was used as inspiration when designing the different task.

Table 1 provides an overview of the rules of the ordinary card, the task added, and the hacked card’s new purpose.

The hacked task has been translated to English, from the original Danish, for ease of understanding.

| Card | The Original Rule | The HACKED Purpose | The HACKED Task |

|

|

|

|

“Ask the next player what they want to drink. Get it and while the next player is drinking they lose their turn” |

|

|

|

|

“Before next player draws two cards, tell them your name and your favorite ….”

Each card had a different subject to talk about: Favorite color, candy, animal, song/music; work/study; last night’s dinner; age |

|

|

|

|

“Switch seat with the person …. The turn proceeds the same way”

Each card had different orientation: to the right, to the left, across, directly |

|

|

|

|

“When you play this card, you have to tell about something mentioned earlier in the game”

|

|

|

|

|

“Before you play the card, you need to tell..”

Each card has different questions: For example: what you think is hard, what you dislike, a bad habit, what is nice, etc. |

|

|

|

|

“Give a high-five to the one left/right to you”

The card adds a new rule as well “When the task is done, put down a card you choose yourself” |

|

|

|

|

For example:

“Everyone must take turns making a wish for the future. Afterward, everyone must throw an optional card at the bottom, without the task to be solved. If you are left with only one card, say UNO. The player who played the card gets an extra turn.” |

Materialization of HACKED UNO

As already argued, with the hacked game design, I intended for UNO‘s “basic” rules and goals to remain the same. I needed to find a way of adding the HACKED cards’ new tasks in a way where the players didn’t need a big rulebook beside them to understand the cards’ roles and the latest game dynamics. Furthermore, the cards still needed to be recognizable so as not to disturb the game too much. I measured the dimensions of the cards and made a template (Figure 2) for the card design in InDesign. I marked up the middle of the card and added a new feature with a description of the card’s attribute in the middle of the card.

After adding the text to the template, the template was printed on semi-transparent labels, ensuring that both the card’s original rule and the new hacked task were recognizable. The new task was cut out and adhered onto the appropriate UNO card. In the first testing phase, I noticed that the text was hard to read with a transparent background on the card. Adding a subtle grey field made it easier to read the card while still seeing its original features. The adjustment was made, and the new tasks were printed, cut out, and placed on the UNO cards.

This way, I ensured that the card’s materiality didn’t change and still felt like the original set of UNO. Had I used a paper prototype or glued paper on cardboard, it could have changed the player’s perception of the game, impacting the game’s dynamics, or it could have affected shuffling and dealing the cards.

Pilot Testing

A pilot test revealed the findings reported below:

- The text on the card was hard to read.

- The two cards about “how do you feel” and a “future wish” were unclear.

- The rules about switching seats weren’t clear enough.

- The card prompting the player to remember something another player said was slightly unsuccessful when it was played at the beginning of the game, as this card depends on the information elicited by the other hacked cards. If the card was played in the first rounds, it could be that no one has said anything yet.

The text on the cards were adjusted so that the rules were clearer. The card of remembrance gave an extra mechanic for switching the card and shuffling the deck, so the players could choose which mechanic they wanted to use.

Data Collection Method

The data presented for this study was gathered on a single evening at the NGO during their weekly inquiry session, where they typically hang out, cook dinner, and play different board games. Seventeen participants had joined the evening gathering. Two volunteers oversaw the evening to start activities and prepare food. Seven of the young people attending this evening in HUSRUM are volunteering to play the HACKED UNO. They are seated at a long table, with the cards in the middle. There are no volunteers at the table. As the participants played the game together for this study. Video observation was used to collect data for further analysis. Before the record was started, the participants had to sign a consent form due to GDPR. All data presented are anonymized, and names appearing in transcripts are pseudonyms. Besides that, field notes from observations were also written down as a data source.

Qualitative Analysis

After collecting the data, the data was prepared for qualitative analysis. The recordings were explored through a content log. When the reconfigured or hacked cards were played, the time, card name, and a short description were recorded in the content log.

Each episode was transcribed with the CLAN software and the Jefferson transcriptions key.

While the video recordings are data-rich, the scope for the qualitative analysis was narrowed down to the following:

- How do the hacked/re-configured cards support the social setting when played?

- What information from the small story told during the game gives us insights into what it means to be lonely?

To answer the first question, the findings in the section below were described with inspiration from conversation analysis, henceforth CA , to show how the game provided a structure and helped the young adults train simple small competencies like getting someone a coffee. The second question is answered with inspiration from the framework described by De Fina and Georgakopoulou, as mentioned earlier, used to analyze and identify the small stories which align within the in-situ social practices that occur when the participants are playing the social game. These little stories are also discussed inside the loneliness theorem.

Analysis Method

The methodological approach used for analyzing and understanding the data is inspired by Bamberg, De Fina, and Georgakopoulou, with inputs from the classic conversational analysis (henceforth CA) approach provided by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson. In the analysis of this study, I use a mix of CA, combining fine-grained transcriptions as the Jeffersonian transcription regime with those of the Mondada conventions. This combination allows for a focus on more than just talk. The Jeffersonian transcription regime shows not only what has been said, but also how it is said and when it said in an interactional setting. The Mondada transcription conventions can add even more details, especially gaze, body movement, and other bodily functions to reveal and understand what is happening in the interaction. Both the Jeffersonian and the Mondada systems can be more or less detailed depending on what the researcher wants to investigate.

Bamberg and Georgakopoulou have discussed different approaches to using transcripts in academic discourse. There are statement transcriptions, which consist of statements or single fragments from an interview used to show a point. This way of transcribing is what Bamberg and Georgakopoulou refer to as a macro transcription. The macro transcription is also the first step while processing the collected data.

While macro transcriptions provide information on what has been said. It leaves out the more interactionally relevant features, such as turn-taking and agency for saying the utterances, making it hard to answer what is happening in the interaction. More fine-grained transcriptions can provide more details on what happens in the interaction on a micro-level and provide insights into the interactional system used for communicating.

All in all, the transcription that is made based on recorded data relies on the choices which are made during the processing of the data. Transcriptions can be constructed in less and greater detail, either as statements showing what is said or as multimodal descriptions of what is going on the interaction. As argued by De Fina and Georgakopoulou,

“…transcription and translation are not seen as transparent processes, but as choices with strong implications for data analysis. Equally, it sees dichotomies such as natural versus elicited data as fundamentally flawed because it is committed to exploring how any setting in which narratives occur brings about and is shaped by different norms and histories of associations, participant frameworks, relations, etc. From a methodological point of view, the SIA does not set out to sanction or prescribe certain ways of working at the expense of others. However, its epistemological framework lends itself better to ethnographic methods that allow for local, reflexive and situated understandings of narratives as more or less partial and valid accounts within systems of production and articulation.”

Thus, it is essential to note that the choices made when transcribing have an impact on which details the data will show. In this study, I have used fine-grained transcriptions where focus has been on what is said and how it is spoken in the interaction. Also, to show how the game provides agency for the interactional situation, the transcript has different types of body movement incorporated. The transcription key used, can be seen in Table 2: Transcription key.

| Symbol | Meaning |

| *NAME | Utterances by the person |

| %name | Description of gesture or bodily adjustment by the person |

| (1.72) | Pause in seconds |

| (.) | Pause under 0.5 seconds |

| = | Continuation maker from previous line |

| Smile in voice | |

| : | Extension of vowel sound in word |

| ↓ | Shift to low pitch |

| ↑ | Shift to high pitch |

| [ ] | Overlap in speech |

Analysis

How the Cards Helped Train Small, Everyday Competencies

As described in the theoretical section regarding loneliness, the young people need to develop some competencies. Some of the HACKED UNO cards are designed to support small, everyday routines in a specific social setting that could occur at different institutional praxis (e.g., educational institutions, workplace, etc.). One of the cards, for example, was supposed to promote helping and doing a good deed for another person by offering and serving a drink as the primary objective. It can seem relatively straightforward and ordinary, but as I noticed in my initial observations, when some lonely young adults were requesting something like water or other materials, the recipient didn’t always understand what happened. Therefore, communication tends to fail in the interaction. The analysis of the transcription shows how the card forms and helps shape the conversation and the exchange. The extract below [translations following ||] shows how the card helps the interaction succeed and trains the informal alignment of doing a good deed (in this case, HEN provides NIK with a cup of coffee).

Extract 1

- %kim: ligger et kort (3.27) || %kim: puts down a card

- *HEN: er det mig øhh:: hent et glas vand (.) kaffe eller te eller anden drik efter ønske (.) || *HEN: is it me uhh:: get a glass of water (.) coffee or tea or other drink after wish (.)

- =til den næste spiller || =to the next player

- *KIM: serius ej ((latter)) || *KIM: seriously ei ((laughter))

- *HEN: han springes over da den næste spiller drikke drikker || *HEN: he is skipped when the next player drinks

- *NIK okay jeg skal bestille || *NIK: okay so I must order

- *HEN: jaja jeg skal hente din kommentar (.) så det dig hvad vil du gerne ha || *HEN: yes yes, I’m going to pick up your comment (.) so it you what would you like to have

- *NIK: jamen jeg vil gerne have kaffe || *NIK: well, I’d like coffee

- *HEN: kaffe skal jeg se om jeg kan finde noget kaffe || *HEN: coffee I need to see if I can find some coffee

- %hen: rejser sig op henter kaffe || %hen: gets up fetching coffee

The first part of the extract, specifically lines 2 -3, shows HEN reading the card aloud and adding what he needs to do for the game to continue. KIM is interrupting and telling her opinion on what she thinks about the task. While HEN, in line 5, reads the last sentence on the card aloud. A new sequential activity is then started, and NIK is taking his turn by asking a question regarding if he has understood the card’s task the right way, as a part of the adjacency pair, while HEN responds confirming NIKs request for confirmation. HEN is also adding a new question as a post-expansion, directed to NIK with a proposal of what he shall provide to him as a part of the small task. In the response, NIK wants a cup of coffee (line 8), and HEN then confirms that he has understood that NIK would like to have some coffee, and he closes the activity by announcing that he is looking for some coffee for NIK.

As shown in the description on the transcript, we can see how the card supports the small everyday activity of asking someone what they want or prefer to drink. By organizing and helping structure the interaction, the game makes the turn-taking manageable. The card’s written task starts by pinning down that the player playing the card must ask what the next player wants to drink. It provides the players with multiple choices, with three options for the player. The intention of giving the player various options to choose from was to provide some explicit examples. The player does not need to think about what they want to drink but casually can select one option and continue the game. So, when the player is reading the card aloud (lines 4-5), the next player has time to prepare and respond without delaying the game and extending the magic circle to include other activities other than just playing the game.

The following extract [translations follow ||] took place during the same session. It is LOU’s turn to play a card; after long consideration, she finally decides to play it. The intended design of the hacked card is to help the players train small-talk situations. The card tells LOU that she shall mention something she thinks is hard to do.

Extract 2

- *LOU: hm::

- (3.456)

- LOU: ja det er et godt ☺spøgsmål☺ || LOU: well thats a J good question J

- (1.728)

- *LOU: hm::: (.) jeg synes at matematik er svært || LOU: hm::: (.) I think math is hard

- %ges: NIK nikker || %ges: NIK nods

- *NIK: ohkay || *NIK: okay

[…]

- *CHR: tar du så noget matematik eller hvad || *CHR: do you take any math training or what

- (0.618)

- *LOU: var || *LOU: what

- *CHR: tar du så noget matematik eller hvad↓ hvis du synes det er svært || *CHR: do you take some math or what ↓ if you think it’s hard

- *LOU: nåh:: nej jeg har en bachelor || LOU: ouh:: no i have an BA

The extract starts with LOU (lines 1-2), indicating that it is her talk-turn with her “hm,” followed by a more extended break. Lou pauses before her utterances (line 3) to raise awareness to the other players that she is still playing. She is, as Hofstetter describes, using the utterances to pre-allocate her game turn and giving herself some time to think before she reacts. The next part of the transcript (line 5) shows LOU answering the question the card has asked, ending both her talk- and game-turn. NIK (line 7) is nodding, accounting that LOU is finishing both turns, and indicating that the next player can start their turn.

Later in the sequence (line 8), CHR asks LOU why she does not take math lessons; the small break in line 9 and LOU’s response in line 10 show that she is unaware of what he is saying. CHR is then (line 11) elaborating on what he previously asked LOU by adding a second part, “…if you think it is hard.” LOU does not understand CHR’s discourse; therefore, LOU is accounting for her education.

By training this as a playful and safe setting – it can be assumed that the young adult is getting confident in asking questions and starting small interaction sequences that can further help navigate them through everyday mundane social activities without getting nervous or backing down in social settings. The cards provide help for structuring and starting a small conversation that is easily transferable to other situations. My analysis shows how the cards’ design impacted how the participants interacted with each other, not only in situ where the card was played, but as a conversation starter between rounds where other actions were performed.

Identity Shaping through Small Narratives and Identifying Symptoms of Loneliness

An example from the analysis shows how the small-talk activities transform into small stories regarding how participants are shaping their identity in the group through different small narratives. According to Bamberg , identity and identity work in a narrative analysis can be seen as how the actors position themselves in the interaction by the agency provided to them. When the actor uses “I”, it suggests something about oneself that positions themselves and builds on the construction of their own identity. Bamberg states that due to the narrative analysis, there are three parts which show the identity constructed as the teller accounts for how they have emerged (as a character) over time, as different from others (but same), and how they view themselves as a responsible agent.

In the extract below [translations following ||], one of the players had played a card when the card prompted them to make a wish for the future. In the section from the video analysis, we see examples of how the different small narratives help shape the participants’ identities in the context of meeting at an NGO for lonely young adults.

Extract 3

- %cha: trækker et kort || %cha: draws a card

- *CHA: uh: || *CHA: uh:

- %cha: kigger på kort (2.0) || %cha: gaze at cards (2.0)

- *CHA: okay den her er anderledes den har vi ikke haft før (.) || *CHA: okay this one is different we haven’t had that yet (.)

- *CHA: =alle skal på skift komme med et ønske for fremtiden || *CHA: =everyone should take turns to make a wish for the future

- *CHA: øhm:: || *CHA: uhm::

- *CHA: så jeg vil gerne ((utydeligt)) || *CHA: so I’d like to ((indistinctly))

- *NIK: ohkay || *NIK: ohkay

- *CHA: jeg vil bare gerne have at det går godt ohkay || *CHA: I just want it to go well ohkay

- *NIK: mhhm (.) || *NIK: mhhm (.)

- *CHA: heh || *CHA: heh

- *CHA: heh (1.2) || *CHA: heh (1.2)

- *KIM: øh: jeg ønsker at je::g↓ (.) blir gladere↑ || *KIM: uh: I wish to ↓ (.) get happier↑

- %hen: nodding

- %nik: nodding

- %vik: nodding

- *CHR: det håber jeg også || *CHR: I hope so too

- *KIM: hehe || *KIM: hehe

- *CHR: jeg skal snart til at skrive speciale så det (.) ⌈øns⌉ker jeg det går godt || *CHR: I’m about to write my thesis so that (.) ⌈hop⌉es it’s going well

- *CHA: u⌊hh⌋ || *CHA: u⌊hh⌋

- *KIM: hvad skriver du i || *KIM: what do you write in

- *CHR: (.) matematik (.) || *CHR: (.) Mathematics (.)

- *CHA: uhh matematik er også ((utydeligt)) det er svært || *CHA: uhh math is also ((indistinct)) it’s hard

- *KIM: nice || *KIM: nice

- *CHA: pyha ja || *CHA: phew yes

- *KIM: ja pyha || *KIM: yes phew

- *LOU: jeg hader matematik || *LOU: I hate math

- *CHA: så er det bare foran dig || *CHA: then it’s just in front of you

- *LOU: ja (1.77) || *LOU: yes (1.77)

- *LOU: ja jeg tænker også såda noget med jeg vil blive gladere håber jeg || *LOU: yes I’m also thinking so something with I’ll be happier I hope

- (2.3)

- *NIK: øh::: jeg ønsker mig succes || *NIK: uh::: I wish myself success

- (6.592)

- *HEN: je::::g ønsker mig at blive ((utydeligt)) || *HEN: je::::g wants me to stay ((indistinct))

- (3.18)

- *VIK: jeg håber det lykkes mig at blive sygeplejeske || *VIK: I hope I succeed in becoming a nurse

- (1.82)

- *CHA: det håber jeg også for dig || *CHA: I hope so for you too

- (1.93)

- *CHA: nåh: || *CHA: Oh:

The first example of how identity is built occurs in line 13, where KIM is stating that she would like to “be happier.” Considering loneliness, this is an interesting statement because the interpretation of why she isn’t pleased differs in theoretical literature. But due to the little narrative that KIM is telling about herself, we might assume that she has the impression of herself as an unhappy person. KIM’s narrative that she talks into is a standard description of how lonely people often describe themselves as Peplau writes: “Complementing how others see lonely people, lonely individuals themselves report such feelings as sadness, a sense of estrangement and rejection by others, a lack of self-confidence, boredom, anger against others, and depression.”

The little narrative structure is also structured as Labov and Waletzky have described. KIM’s small story starts with her utterances, then her peers nodding in the middle, and it ends with the CHR taking the turn and agreeing with KIM; he shows empathy towards her.

KIM’s story reveals different aspects of her identity construction, according to Bamberg. She is positioning herself as “an unhappy person” by adding that she wants to be happier” in the future. With the utterances, she is comparing herself to a societal discourse about being happy; she wants the same even though it differs from her current state of mind. Her identity works as it appears in line 13 according to Bamberg also work on her identity. She accounts implicitly for her current state of mind as she positions herself as someone who “wishes to be happier”. She indicates a change from happy to unhappy and wants to return to her happy state of mind. The identity work she is doing in the line shows a conflict between happy and unhappy, which might have a coherence with her loneliness.

Another example of how the wishing card reveals other narratives about the player and their struggle with loneliness is when LOU, in line 26, follows up on KIM’s earlier utterances and says she would also like to be happier. LOU’s utterances show once more that some lonely adults identify themselves as not as satisfied as they wish to be. This places a discrepancy between how they feel in their current state and how they want to be.

According to Peplau, lack of self-confidence is also a side effect of loneliness. VIK is in line 32 indicating a lack of self-confidence – “She hopes she will manage to be a nurse.” With her statements and the choice of using the word “håber/hopes,” she is displaying a lack in confidences at her skills and seems unsure that she will finish the nursing education. The lack of self-confidence shown by VIK is a Peplau describes as a typical side-effect of loneliness. It makes one doubt if they can perform the task they are attending. According to Bandura (1986, 1990), a person with low self-confidence will likely not maintain or accomplish their goals.

The doubt VIK is showing by using the verb: “hope” shows that she is not sure if she will manage to complete her educational goals. The extract above also shows how one participant does not lack self-confidence in the educational setting. CHR is in line 15, saying that he wishes his MA in mathematics would result positively. His utterances show in opposition to VIK; he has CHR confidence in his educational work and has no doubt that he cannot finish the study he has started.

To summarize the findings in this section, the analysis shows that the card game can be used to get insights into how different states and experiences of loneliness can be expressed in a situation where the game is being played. Despite that, the cards do not directly ask questions about loneliness; some of the players, probably due to the situated context/discourse (they are all coming to the NGO due to loneliness), provide us with information about how loneliness is shaping their identity as individuals based on their telling of small stories.

The Small, Open-Ended Story

Traditional narratives are generally considered with a beginning, a middle, and an ending. As earlier mentioned, sometimes histories and extraordinary in-situ records, where the responses are spontaneous and now, in contrast to interviews and other reflexive praxis. For sensemaking, it is necessary to emphasize the epistemologically turn-talking stance from CA to show the point of small open-ended stories as an in-situ interaction phenomenon. The small open-ended story often occurs in my data set, where the verbal or bodily accounting fails.

In the extract above, at line 27, a small open-ended story appears where the ending or closure does not occur.

LOU states that she “really hates math” the trigger is the CHR response about the card question. LOU is setting up a new personal narrative about her academic preferences, or rather, her academic dislikes. LOU statement is a consequence of the card’s performed action, and LOU contributes to an ongoing conversation. Still, after her statement, the prior discussion stops, and CHA switches the topic and invites LOU to continue the game. This has consequences for the small story that LOU has started. It does not get an ending, so the narrative or small story is unredeemed.

Discussion

As outlined in the introduction, I have tried to transfer a known leisure game into a social game, as described by Markussen and Knutz, by adding a small task that was intended to help as a catalyst for interaction and with the dual purpose to helping the young adults train some social skills which their due to loneliness has devolved and needs to practice, and also see if it could provide information on how loneliness can directly be seen in the interaction.

The Multiple Purposes of HACKED UNO

As earlier stated in this paper I position three ways of games purposes could be used. I will argue that the HACKED UNO, is positioned in the middle of the social-, serious and design game sphere, because it can be used for different purposes at once.

HACKED UNO as a Serious Game

As seen in the first part of the analysis, I have described how the game shows potential for helping young adults to train and perform different kinds of tasks; there possibly can be transferred into other situations and regular meetings, and the cards provide a structure for the young adult to train and act in the playful setting, e.g., how to ask someone what they want and how to engage in small talk session for letting one to know each other. Even though the cards facilitate these talks, the game needs some design changes to better support or make the reflexive part of how they can use the skill they acquired from the game in their everyday life.

HACKED UNO as a Social Game

Another issue with the design got visible when analyzing the data through the lens of the open-ended narratives as described by Bamberg and Georgakopoulou, the way of not seeing the small stories as traditional narratives with a BME, showed other implications for the game’s interactionally purpose which didn’t appear in the narrative praxis through conversation analysis. As described in a previous section, LOU is starting to form her identity through a narrative with a statement regarding her academic skills in mathematics. Still, as described, the conversation doesn’t evolve further. It just ends up and not being picked up later. Lou’s story is not being told, and the background and small polite, curious questions are not being asked. Seen from an interactional perspective that gazes through the eyes of Huizinga’s magic circle, it can be discussed that LOU is breaking the magic circle with her statement because it wasn’t her turn. The missing response is a sign of that. This indicates a design implication for the game; the game needs to create space and time for questions and reflections as a part of the game’s mechanics.

Further research needed to be done with the participants to know exactly how these features should be incorporated into a social game.

Conclusion and Further Work

In this paper, I have explored in-situ interactions where self-assigned lonely adults play a hacked game that prompts them to talk and do everyday situations. As I have shown in the analysis, we get insights into how loneliness can occur in different positions and that a descriptive narrative analysis of how the interaction plays out can be used as a way of seeing how loneliness is happening either on how the conversation is being shaped or simply the missing link in the interaction. Using social games as a catalyst for shaping social interaction can help the target audience, in this case, the lonely young adults can train social skills.

For research purposes, we are getting knowledge on how loneliness shows in everyday situations.

This paper explores how you can transform a leisure game into a social game to investigate if a playful approach could help lonely adults interact and get to know each other. As I have shown, the game helps young adults train social skills as a part of a serious game framework, It provides valuable information on how loneliness appears in a social setting and at least tries to push the border for letting the young adults reflect over their own identity.

–

Abstract:

This paper investigate how social design games may support interaction between lonely young adults that due to long-term loneliness need to train social skills which later can help them out of their loneliness. A leisure game was hacked based on previous fieldwork and presented for lonely young adults. The game was played and the inquiry was video-recorded with a group of attendees and the data was transcripted and analyzed within a narrative and small story approach. The findings from the data showed that social design games can help lonely young adults to train social competencies.

Keywords: card games, UNO, social design, serious games, leisure, loneliness, player psychology

–

Featured image by Mads Grønne Bärenholdt

–

Mads Grønne Bärenholdt is conducting research on social design, using various design games to carry out ethnographic fieldwork in vulnerable communities. His work places a strong emphasis on sensitivity and care for participants, ensuring that their well-being is prioritized throughout the research process. Currently, Bärenholdt is finishing a PhD project at the University of Southern Denmark that explores the perception of loneliness and how it becomes visible through interactions and narratives during gameplay with different types of games.