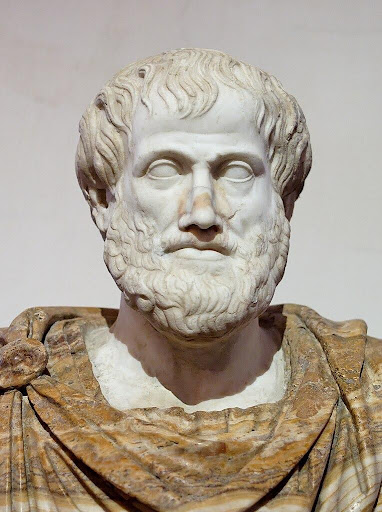

“Aristotle’s poetics, although occasionally so deeply embedded as to be almost invisible, remains the stable foundation for the theory of genres.” ~ Mikhail Bakhtin, Epic and Novel

This article proposes to examine Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) adventures as a genre. By genre I mean both the traditional understanding of genre as a literary tool for categorizing texts but also the notion of genre as a cultural artifact that is functional, structural, and constitutive of an experience (in this case, the experience of playing a tabletop D&D adventure). Genre analysis is important because it helps us understand the social function of a text. On a practical level, genre analysis helps us write better adventures by identifying structural and stylistic patterns, encouraging criticism and comparative analyses, understanding reader expectations, and inviting examination of the evolution of adventures over time. In short, genre analysis helps us understand how and why a text successfully accomplishes its purpose. I argue that Aristotle’s Poetics serves as a felicitous starting point for the analysis of D&D adventures as a genre, not only because of its foundational nature to this field, but also because of the similarities between theatre and TTRPGs in general, but also the nature and experience of tragedy and D&D adventures in particular.

Adventures are the heart of D&D and all tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs). Analyzing them as a genre offers a way to bridge discussions of game content and game mechanics. Ian Bogost’s self-critique of his landmark book Persuasive Games acknowledges the limitations of mechanics to translate into learning and changes of players’ attitudes. Game designers provide the mechanics, but the players and Dungeon Master (DM) have agency and control over the game, including which rules they choose to enforce. This is a quality unique to TTRPGs because of their interactive and cooperative nature. D&D is “narrative play” that combines a rules system and a narrative world, but the former is at the service of the latter to facilitate collaborative narrative creation. As the 5th edition Dungeon Master’s Guide informs us: “the rules serve you, not vice versa.” Genre is structural but different from game mechanics. Following the “rules” of the D&D adventure genre helps create successful play sessions.

D&D has attracted research from its earliest days. Gary Alan Fine’s 1983 ethnographic study remains paradigmatic. Whether the approach is anthropological or psychological, the experience of players is a primary axis of research into TTRPGs. Much of this research revolves around the social, cognitive, and psychological benefits of playing D&D. A large body of empirical research attests to the benefits of playing TTRPGs. Baker, Turner, and Kotera review recent research into the mental health benefits of playing D&D. They contextualize gameplay in the domain of drama and narrative therapy. Summarizing the research of over a dozen studies they conclude, “Playing D&D can aid in friendship and relationship maintenance, mitigation of social anxiety, improved social skills, reducing stress, alleviation from mental health challenges, and providing connection with others.” A larger scoping review by Arena, Viduani, and Araujo of over four thousand studies covering RPGs of all genres concludes that RPGs can serve as a “complementary tool” for psychotherapy. Yet this research possesses a puzzling lacuna. The content of the game is either unexamined, taken for granted, or treated as incidental to the benefits, primarily deriving from its social aspects, of the play experience. Despite research into the benefits of playing TTRPGs, analyses have overlooked D&D adventures. An analysis of the benefits of D&D is thus far incomplete without considering the content of play.

Some D&D research does examine content, but it is typically focused on the game’s rules. In many cases, researchers identify tropes common to fantasy genres. Garcia and other scholars argue that game systems such as D&D embed cultural norms and biases relating to race, gender, and power. Garcia’s analysis explicitly focuses on core rules rather than adventures. Similarly, Albom examines the core rules to critique D&D for putting violence at the core of the player experience, and minimizing alternatives to it. Stang and Trammel study the Monster Manual (one of the three core rule books) to reveal the prevalence of misogynistic tropes. Hines’s excellent analysis of The Tomb of Annihilation is one of the few studies to critically examine an actual adventure, making a connection between game mechanics relating to race and content, in this case tropes relating to colonialism.

Perhaps the reason why there is so little research on content is that this requires researchers to confront agency and reception. An analysis of game rules avoids this difficulty. Yet the research that does take agency and reception into account challenges some mechanics/systems analyses. For example, studies of actual play shows such as Critical Role demonstrate the influence of audience reception on influencing their content. A recent study by Ferguson also shows the importance of reception. He surveyed 306 individuals to specifically investigate D&D’s depiction of orcs. His analysis revealed that playing D&D did not increase ethnocentrism and that people of color were not more likely to view depictions of orcs as racist. Or consider critiques of D&D for the prevalence of violence. Wright, Weissglass, and Casey conducted qualitative research over six D&D game sessions that embedded moral dilemmas. The potential for violence was an essential element of the dilemmas. Yet they conclude that D&D is an efficacious tool for teaching moral reasoning specifically because the potential for violence exists in its world. Illustrating the importance of content, in this study the moral dilemmas presented were part of a homebrew adventure where “prosocial violence” was a possibility. Hines’s critique of colonialist tropes in The Tomb of Annihilation is accurate, but reception and agency are key here as well. So explicit is the Heart of Darkness derivation of this adventure that when the author’s D&D group played the adventure the game devolved into a parody of the film Apocalypse Now with each player trying to out Kurtz the others by describing snails crawling on the edges of vorpal swords.

Hammer’s analysis of the nature of agency and authority in role-playing game texts is key to understanding the space between the determinism of rules mechanics and canonical texts and the ability of players, especially game/dungeon masters, to shape and adapt texts. She argues that authorship can be understood on three levels. The “primary” author makes the system, the world, and the rules. “Secondary” authors take the system and make scenarios. “Tertiary” authors create their own text or narrative using the system and scenario to play the game. Hammer uses a theatre analogy to explain the three tiers: “If the primary author creates the sets and costumes, and the secondary author provides the script and outline, the tertiary authors are the ones who bring the story to life.” Secondary authors arguably have the most precarious authority in a TTRPG: caught between canonical system texts and agentic players. Thus, there is a complex relationship between the authority of texts and authors, on the one hand, and the agency of players on the other. Nevertheless, there are limits and constraints on tertiary authors and player agency if they want to play the game as such. The constraints to agency are strongest in the digital context where choices are coded, but they exist in a negotiated form in TTRPGs. To rephrase Karl Marx’s famous dictum from The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, “players make their own narrative, but they do not make it just as they please.”

Understanding TTRPG adventures as a genre bridges the gap between an analysis of game mechanics and assessing the agency and reception of players in relation to their experience playing specific adventures. That is, a genre understanding of adventures allows them to be treated structurally. In addition, as regards agency and reception, understanding TTRPGs as a genre helps us to approach them in terms of their purpose and the experience of players. Mechanics matter, content matters, and so does player agency.

Dungeons & Dragons as Theatre

There are two steps to my argument on the utility of using Aristotle. The first is to establish that D&D can be treated as theatre. If this is the case, then it follows that Aristotle is the necessary theoretical starting point for an analysis of adventures as a genre. Aristotle’s discussion of tragedy in Poetics contains ideas which grew into traditional genre theory, that is, prescribing elements and characteristics necessary for a text to be included in a literary category, but crucially he also discusses the social and experiential role of texts. Aristotle’s limitations have been examined in detail, particularly in the context of gender and misogyny. I propose a close reading of Poetics not as a defence of Aristotle, but as a starting point because of Gary Gygax’s explicit acknowledgement of this text’s influence on his approach to and understanding of D&D. In an interview with Gary Alan Fine, Gygax offered this explanation of D&D:

Not to be pretentious, but the rules for D&D are like Aristotle’s Poetics if you will. They tell me how to put together a good play. And a [referee] is the playwright who reads these things and puts his play together.

The theatrical nature of the game is explicit in the 1st edition AD&D Player’s Handbook:

As a role player, you become Fallstaff the fighter. . . . You act out the game as this character . . . Each of you will become an artful thespian as time goes by—and you will acquire gold, magic items, and great renown as you become Falstaff the invincible!

In a detailed theoretical piece Nellhaus argues that RPGs—both online and analog—are theatre and should be analyzed and discussed as such. Nellhaus uses the term genre primarily as a categorization tool for a text, in this case a type of performance, although the experience of participants is a trait used to understand the category. He argues that the key elements of theatre—presence, space, and embodiment—are fundamental to gameplay in a RPG. Furthermore, he argues that theatre and RPGs possess the same ontology based on social structures, agents, and discourses, and a theatrical event that requires both performers and spectators to maintain a dual conscious of the factual and the fictional worlds they inhabit.

Shared genre conventions offer another clue for understanding D&D as theatre. A key shared convention is the use of descriptive text. Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard opens with the following text that describes the stage when the curtain rises on Act 1:

A room which is still called the nursery. One of the doors leads into ANYA’S room. It is close on sunrise. It is May. The cherry-trees are in flower but it is chilly in the garden. There is an early frost. The windows of the room are shut. DUNYASHA comes in with a candle, and LOPAKHIN with a book in his hand.

Descriptive text is also used by dramatists throughout scripts. For example, in the play Hippolytus at a point when Theseus, the exiled king of Athens, enters Euripides provides this description:

Enter Theseus, attended by the royal guard. His head is crowned with the garland worn by those who have received a favourable answer from an oracle.

Dramatist call text that describes the stage when the curtain rises the “at rise” description. Such text is an important genre convention in theatre. Genre conventions are components, formula, and structures of writing that help writers meet expectations of a discourse community. Genre conventions, explains Duff, are “tacit agreements between the author and the reader (or audience) that makes possible certain types of artistic representation of reality.”

There is surprisingly little written about “at rise” descriptions in drama theory. Most writers treat this text simply as instructions to provide to set designers and directors. In Playwriting: A Practical Guide Grieg explains: “There are many opinions about how much information and detail the writer needs to supply for the director, designer, lighting designer and sound-artist in order to realise the physical embodiment of the story. My own taste is to be minimal, and to allow as much scope to the other artists as possible.” Wandor argues that the purpose of such text is to “compensate for something the dramatist has been unable to do” and “in any case, stage directions can never compete with their equivalents in the novel.” The existence of this text is an acknowledgement of constraints, but the necessity of it could be interpreted as a deficit of the dramatist’s skill or indeed a misunderstanding by the dramatist of how to use the affordances of theatre rather than compensating for its constraints. The ambivalence of theorists about “at rise” or descriptive text, and the uneven discussion around it, aligns with Aristotle’s dictate that Spectacle (costumes, set design, and other physical elements) is the least important of the six elements of tragedy.

D&D adventure writers employ descriptive text in the same way as playwrights use “at rise” descriptions. Called read-aloud or boxed text (because it is typically set outside from the other text in a box), the 1980 adventure module The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan marks its first appearance. The adventure opens with the following boxed text that the DM is instructed to read to players:

Breathing heavily, you find that the world has stopped tumbling and you now sit on cold, damp stone. The coughing and wheezing of your companions can be heard nearby, hidden in the darkness. To your back are rough rocks and broken earth. As you sit, the rumble and clatter of rocks diminishes to the occasional rattle of pebbles and the shush-shush of sliding dirt.

The read-aloud text sets the scene for the players to begin acting their characters. Read-aloud text is analogous to “at rise” descriptions. Cover offers one of the few—perhaps the only—academic discussions of read-aloud text in TTRPG adventures. Cover addresses read-aloud text in the context of her over-arching argument about narrative agency as the defining characteristic of TTRPGs. She argues that such moments of “oral description” called for by the read-aloud text contribute to game narratives. Cover shows, for example, how the read-aloud text helps players construct chronologies. However, Cover does not connect read-aloud text in TTRPGs to the “at rise” description in theatre. Her main concern is to show that descriptive read-aloud text does not disrupt the potential for agentic game narratives.

The authors of The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan instruct DMs to read the boxed sections to the players. They explain its purpose:

The players’ descriptions are provided because many of the encounters require specific actions on the part of the group. Hints of what may be done are given in this text and the DM should only provide vague information if questioned.

Read-aloud text is, in short, an aid to players. It offers clues and the frames narrative boundaries.

TTRPG writers grapple with read-aloud text as part of their craft in the same way playwrights approach “at rise” descriptions: as a challenging but essential element of the genre. The prolific D&D author Michael Shea, arguably showing how the understanding of the genre is more advanced among practitioners than academics, makes an explicit connection between read-aloud text and drama: “if our D&D game is a Broadway show, our read-aloud text is part of our script.” Shea recommends short text that has a specific purpose of revealing something essential to the players. Merwin, writing for the official D&D site D&D Beyond explains that read-aloud text is “as much a part of D&D’s history and brand as saving throws, hit points, and armor class.” He acknowledges criticisms of read-aloud text, the primary one being that it can be a jarring, unnatural interruption to the flow of the game. However, he argues that well-written read-aloud text is necessary for “setting a scene” and can be as useful to DMs as it is to players. A Twitter poll by D&D’s current lead rules designer Jeremy Crawford saw 2,248 replies to the question “How much boxed text (aka read-aloud text) do you like in an adventure you run?” The results were 59.5% desired “occasional boxed text,” 34.4% “lots of boxed text,” and only 6% of respondents did not want any boxed text.

This discussion of read-aloud text shows that D&D adventures share an important genre convention with theatre. Read-aloud text in adventures is further evidence of the applicability of drama theory for the understanding of this genre. Furthermore, one of the co-creators of the game itself, Gary Gygax, characterized the DM’s job as that of “playwright” and conceptualized the experience of players as theatrical performance. D&D is theatre, and we see its nature both in the experience of participants and its observance of the conventions of the genre.

Aristotle’s Poetics

Recent scholarship also supports the use of Poetics to help us understand game narratives. Tan and Mitchell apply the three main elements of Aristotle’ schema in Poetics (Katharsis, Anagnorisis, and Peripeteia) to an analysis of the computer games Disco Elysium and Her Story. They suggest understanding these “dramatic narrative logics” make for immersive, agentic gameplay. Similarly, Bizzocchi and Tanenbaum use Poetics as methodology for a close reading of the narrative in the videogame Mass Effect 2. My analysis treats D&D as theatre and therefore uses Poetics to explicate its adventures in this genre.

Aristotle provides a summary of the purpose and nature of tragedy in Chapter 6 of Poetics:

A tragedy, then, is the imitation of an action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself; in language with pleasurable accessories, each kind brought in separately in the parts of the work; in a dramatic, not in a narrative form; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions.

Aristotle then identifies the six parts or “formative elements” of a tragedy and orders them in importance: plot, character, thought, diction, melody, and spectacle. Plot, the actions and events of the story, is the most important, and according to Aristotle, requires two key elements to draw in the audience: peripety and discovery. Discovery refers to learning critical piece of information, usually about the truth of a person, their condition or true nature, and the discovery could be as much a surprise for the character concerned as for others. Peripety refers to a reversal of fortune for a character, typically a dramatic change of circumstances. Aristotle gives the example of the character Danaus from Theodectes’ play Lynceus. Danaus was going to kill his brother Lynceus but at the last moment he is saved and Danaus is executed. Aristotle has thus set a goal or function for tragedy, what he calls “poetic effect,” and prescribed a method to achieve it. The elements of a tragedy all work together to produce the poetic effect: a buildup of the emotions of pity and fear followed by catharsis and wonder. “You have witnessed horrible things and felt painful feelings,” explains Sachs, “But the mark of tragedy is that it brings you out the other side.”

As theatre, D&D adventures map nicely to Aristotle’s six elements. We see his minimization of spectacle, for example, mirrored in the D&D community’s debate on “theatre of the mind” combat. Some players prefer tabletop grid maps and the use of miniatures while others eschew physical props. For Aristotle, the mark of a talented writer is to achieve the emotions through the plot rather than props: “Spectacle is more a matter for the costumier than the poet.” Similarly, as regards melody, the use of music at tables is valued by some players, as evidenced by the proliferation of D&D playlists (most of them ambient) on Spotify, and ignored by others.

Unsurprisingly, plot is where see the closest alignment between Poetics and a D&D adventure. Here the crucial element is agency. Aristotle outlines three forms of plot to avoid due to their inability to evoke emotions of fear and pity: good people should not go from happiness to misery, bad people should not go from misery to happiness, and an “extremely bad” person should not go from happiness to misery. None of these three plots provoke pity and fear. Although the first plot may provoke pity, it does not provoke fear, according to Aristotle, because this requires that we see the person “like ourselves.” Pity on its own is incapable of providing a cathartic experience for the audience.

Agency, in Aristotle’s description, is the key ingredient of a tragedy’s plot: “…the change in the hero’s fortunes must not be from misery to happiness, but on the contrary, from happiness to misery; and the cause of it must lie not in depravity, but in some great error on his part…” Similarly, agency is key to D&D; it is core to the nature of the game. Narrative agency is, according to Cover’s compelling argument, the defining feature of TTRPGs as a genre. Gygax’s discussion of agency and the randomness of dice mechanics in the Dungeon Master’s Guide echoes Aristotle’s thinking of the ideal plot about what is acceptable and what is objectionable. In this section, “Rolling the Dice and Control of the Game,” Gygax famously gives DMs license to alter dice rolls to improve the experience of either the players or the DM. Agency is determinative: “It is very demoralizing to the players to lose a cared-for-player character when they have played well. When they have done something stupid or have not taken precautions, then let the dice fall where they may!”

Likewise, pity and fear are as essential in a D&D adventure as they are in tragedy. The 1st edition Dungeon Master’s Guide sets out a basic template for a campaign: a settlement with inhabitants and Non-Player Characters (NPCs) and a nearby dungeon to explore. Gygax followed this formula explicitly in the introductory adventure for the D&D Basic Set, The Keep on the Borderlands. Gygax again emphasizes agency in a section of the adventure called “How to be an Effective Dungeon Master”: “The players must be allowed to make their own choices. Therefore, it is important that the DM give accurate information, but the choice of action is the players’ decision” (bold in original). Incidents provoke fear and pity. Characters pity the fate of unlucky comrades and the prisoners held by the hobgoblins or the slaves of the Bugbears, and fear for their own, and their friends’, safety as they fight their way through the local dungeon, The Caves of Chaos.

Peripety and discovery are also constitutive components of D&D adventures. The Keep on the Borderlands contains an evil NPC who conceals his true nature from the players, and so does the sample adventure provided as a template in the 1st edition Dungeon Master’s Guide. The more recent adventure Storm King’s Thunder is a remix of King Lear and unsurprising given the source material its NPCs present opportunities for peripety and discovery. The vampire Strahd, the subject of iconic adventures across D&D editions, and the fallen archangel Zariel from Baldur’s Gate: Descent into Avernus, are NPCs that exemplify these elements. Finally, Aristotle identifies the means by which discovery can take place and cites “incidents themselves” as the preferred option, followed by reasoning. This too maps with the structure D&D adventures which are a series of incidents and encounters that progress the plot and lead to character development.

Nor does a D&D adventure depart from Aristotle’s contention that the best tragedies have unhappy endings. An unhappy ending in the context of a D&D adventure does not mean that some or all characters die (a “total party kill” or TPK), but rather that victory came at a price. They and the world changed as a result. Things are not going to be the same again: the dragon is dead, but the village destroyed; the characters defeated the demon lord, but not before it disintegrated a beloved NPC. The conclusion of the adventure with the defeat of the boss is the final action to achieve catharsis and thus bring about Aristotle’s poetic effect. Blood had to be shed to achieve victory. Tragedies, argues Aristotle, contain suffering: “murders on the stage, tortures, woundings, and the like.” In contrast, he states that a comedy ends “with no slaying of anyone by anyone.”

Character is fundamental both to tragedy and D&D adventures. The level of detail provided by the Dungeon Master’s Guide across editions for the creation of NPCs offers clear evidence of its importance. Viewed through the lens of Poetics, D&D is a game where players act as their characters, and the DM writes and acts engaging NPCs. Drama is mimesis and so is the play experience of TTRPGs. Aristotle offers four guidelines for characters: that they be good, appropriate, realistic, and consistent. However, there is scope for interpretation as to the nature of “good” character. Aristotle says that the actions of characters reveal “a certain moral purpose.” He also explains, “Character is what makes us ascribe certain moral qualities to the agents.” D&D incorporates moral purpose mechanically and narratively with its alignment system. Thus, although a lawful evil warlord, for example, may not be “good,” they nevertheless possess a clear moral purpose. The remaining three characteristics are well-known to players and DMs and are required for immersion and group chemistry. Fifth edition D&D recommends a “session zero” where players meet to agree on some common elements and play styles before making characters. The 5th edition Dungeon Master’s Guide also provides guidelines on appropriateness and realism in its sections on a dungeon’s inhabitants, factions, and ecology.

For Aristotle, the poet, dramatist, and painter is powerful because they can show and represent human character, including “infirmities of character,” starkly, visibly, and even with exaggeration, while still believable. Indeed, it is the flaws of the characters combined with their agency that drive the plot of a tragedy. Similarly, flaws are an essential part of character creation in D&D, for both DMs and players. On the player side, 5th edition D&D provides tables for every character to have a trait, ideal, and, importantly, a flaw. The 1st edition Dungeon Master’s Guide provides explicit guidelines for establishing the character, as in their traits and personalities, of NPCs. Nineteen tables allow a DM to randomly determine the “personae” of an NPC. They range from physical appearance, to intellect, level of thriftiness, to what the NPC collects (e.g., coins, artwork, books). The 5th edition Dungeon Master’s Guide provides a chapter on NPCs with eight tables to generate their personality. That character is primary to the player experience is a given, but in understanding D&D as theatre, the importance of DM-generated NPCs comes to the fore.

Conclusion

Poetics serves as the key to understanding D&D adventures as a genre, as tragedy. Aristotle helps us write better adventures. This has implications for writers. It means first of all that we must embrace our role as dramatists writing a text with the distinct purpose of achieving Aristotle’s poetic effect. This requires including difficult topics and posing moral dilemmas. Secondly, we must write with player agency in mind. Poetics, I have argued, provides the formula for D&D adventures, but it remains to the gamers—writers, DMs, and players—to create their worlds. Genre is structural, less constraining than mechanics, but dictates form rather than content. Just as Poetics is deeply misogynistic, adventures following its formula can still deploy racist, neo-liberal, and misogynistic tropes—they will just be “better,” in terms of genre function, adventures. I have argued for the importance of understanding D&D adventures as a genre, but content must continue to be reflected upon, studied, and “repaired.”

D&D adventures are Aristotelian tragedies both in structure and purpose. They are specimens of the genre itself rather than a separate or different category of text to which Poetics may serve as an interpretive tool. The experience of catharsis and wonder (θαύμα, sometimes translated as “the marvellous”) for the audience is the primary goal of tragedy. It is this poetic effect of tragedy, concludes Aristotle, that makes it superior to Epic poetry. D&D player characters resemble the heroes of epics, but it is the tabletop experience of play that sets it apart. As Aristotle explains, “Tragedy has everything that Epic has” but with additional elements—music, spectacle, acting (seeing, hearing, feeling)—that make for a superior experience. Compare the experience between players in a game session and a player who missed the session reading a summary of the exploits of their friends’ characters the previous week—the difference between reading about player-character exploits and creating and acting them. D&D is filled with catharsis and wonder brought about and experienced by agentic player-characters. When we play D&D we are participating in and co-creating a Greek tragedy. This experience is the key to understanding why D&D is so compelling.

As a thought exercise imagine a game session where neither catharsis nor wonder are present. In the author’s case this immediately conjures up memories of the least enjoyable adventures and campaigns—four consecutive play sessions as caravan guards punctuated only by random encounters. Our expectations when we play D&D are to experience catharsis and wonder, the same expectations an audience member has when going to a theatre performance of a tragedy. The D&D tabletop session is a powerful and unique experience, but not without danger. Unsatisfactory adventures are those that deny catharsis and wonder. This risks “moral injury,” the harm suffered by a person when they are betrayed by someone they trust or witness or participate in an event that violates their morals. A D&D adventure, tragedy, inflicts moral injury but by granting agency to player-characters the game allows them to heal the wound by achieving catharsis and experiencing wonder through their own actions.

—

Featured Image is “A Little Night Planet.” Image by György Soponyai on Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

—

Brian McKenzie, PhD is an Associate Professor at Maynooth University, Ireland, where he serves as the subject leader for its First Year program, Critical Skills and also teaches a graduate micro-

credential on RPG writing. He has contributed to several Dungeons & Dragons projects for Goodman Games, and is the author of two forthcoming adventures (also from Goodman Games). His academic research examines game studies, writing, and critical pedagogy.