“Hope keeps us alive and warm and in movement.” These words were written to me by a total stranger. I read them aloud as part of the closing chorus to an environmentalist larp called A Ceremony for Hope while about twenty other players did the same. Among the other messages of comfort that were spoken, I recognized my own words, ones I had written down earlier that evening for someone else to read. The experience was an overwhelming if ambivalent one. I was touched by the outpouring of love and understanding, but I also felt strangely alone.

I played A Ceremony for Hope at Blackbox Copenhagen 2023 (BBCPH), an annual Nordic larp festival attended by larpers from all over Europe. Nordic larp—or live-action roleplay—is a playful, theatrical practice that emerges from traditions of non-profit self-organization in the Nordic countries. It often deals explicitly with serious and difficult topics like oppression, discrimination, mental health, and politics, aiming to raise awareness and create solidarity. This means that the recent upswing in environmental engagement in the Nordic larp scene—the topic of this article—should come as no surprise. The program at BBCPH featured no fewer than four larps that all, to different degrees and in different tones and registers, tackled environmental subjects. They ran the gamut from zoonotic contagion and deforestation, to what I call “dark seasonality,” which describes the thematization of unpredictable and dangerous weather. Inspired by this indication of interest and concern with the climate crisis in the Nordic larp community, this article launches a brief, exploratory study of environmental larp or climate larp, its history, its inspirations, and its recent developments.

The environmental larps I want to discuss can be sorted into three categories for easy comparison. First, there are those that simulate political or diplomatic summits: Pig Grove, Tree of Life, Fortitude, Forecasters, Baltic Warriors. A second category introduces the larps as pseudo-fictional workshops: Cyborg Gaia Allies, A Ceremony for Hope. The third category comprises blackbox larps, which make use of lighting, audio, props, and other means of stagecraft to create spaces for collaborative storytelling: The Ark, Spillover, From the Ashes, Leviathan. To clarify, none of these titles can be counted among the “blockbuster larps” that get most traction in the media. Such blockbuster larps, which include destination larps, generally run much longer; they involve much more elaborate production processes that are months in the making, and a result, they tend to come with an expensive price tag. While there might be larps in this category that integrate climate change or ecological collapse as part of their larger story-worlds, I have excluded them from my review because I have no experience of them.

All the larps I mention in this article are ones I have played (or designed) myself, or read enough about to feel comfortable discussing. Most are Nordic larps by virtue of their circulation and design. Nordic larps are generally played during 4 hour slots at Nordic larp festivals like the aforementioned BBCPH, Oslo’s Grenselandet, Stockholm Scenario Festival, and during the annual Nordic larp conference Knutepunkt. They tend to be costume-less scenarios that can be played in classrooms or in a black box theater, and they require no preparation from players. Moreover, as explained by Johanna Koljonen, in comparison to other larping practices Nordic larp tends to be less “gamist,” and less bound to traditional texts and mechanics, yielding bespoke designs that are fueled by collaborative play. Not all the larps I mention in this article are Nordic larps (though I did come across them in the Nordic larp circuit). I start with a discussion of some more gamist, edu-larps (or educational larps), which take after political simulation games. Edu-larp is another patch of forest in the landscape of larp where environmental engagement has begun to stir, which is why I have found it important to include it, even though as will become clear, I have my reservations about political simulation games. As someone who writes about ecogames regularly, and as a larp designer myself, I have a stake in this form of cultural expression. I therefore include in this article, a discussion of my own larp Leviathan, in the hope that it shows transparency regarding the kind of game-design I engage with myself. Having made myself vulnerable in this way, I hope to stimulate a productive, creative discussion about what I’m choosing to call environmental, or climate larp.

Simulating Climate Politics

The simulation of conflict in games is age-old. Wargames realistically simulate military battles for the sake of research, training, or enjoyment. While climate change is not an armed conflict it is often conceived in ludic terms as a game played in the arena of international relations, producing winners and losers. This metaphor is made literal in playful, educational practices like Model United Nations (MUN), in which players represent countries or organizations tasked to deliberate global challenges according to the UN’s protocols for debate and decision-making. Originating in the 1920s, MUN continued to grow in popularity in the second half of the twentieth century, though it remained confined to educational contexts like schools and universities.

There is considerable overlap in design between political simulation games like MUN and many Edu-larps, which are larps designed for educational purposes. For example, ‘Larp for Climate’ is an Erasmus+ project launched in November 2021 that aims to develop Edu-larps to improve climate literacy and awareness. I have played two brief versions of larps that were designed for the project, and I have read the script of another. Pig Grove and The Tree of Life are both resource management games aimed at younger players like elementary school children. Both dramatize the ‘tragedy of the commons’ by assigning players individual goals and interests that conflict with the group’s interests as a whole. Like many MUN style larps, they pitch iåndividuals against each other using frameworks of competition and scarcity. In my view, the games seem intended to be read metaphorically, to illustrate the difficulty of international collaboration in climate politics. This seems to be the case because while competition and economic growth are often driving factors in international relations, they are much less applicable when it comes to collective land management (Pig Grove) or arboreal ecology (The Tree of Life). It seems to me a missed opportunity to tackle these topics using frameworks like community, collaboration, and symbiosis. Children especially might gain from exploring the benefits of collective stewardship, or learning about the fascinating lives of trees and the networked, multispecies habitats they support.

Fortitude by the design collective Nausika is another larp developed for Larp for Climate. It is a more elaborate political simulation or MUN style larp designed for classroom use. Fortitude asks players to represent either countries or activists, prepping them with short briefs that detail interests, objectives, strengths and weaknesses. The larp takes place in the near future, after global warming has made Australia uninhabitable causing the entire population to have to relocate. The Australian government’s subsequent decision to sell the country has earned them enough money to fund their people’s relocation and to finance an ambitious global climate action plan. It is the players’ task to decide what to spend this money on, choosing between ten ‘priorities,’ only four of which can be funded. These priorities include renewable energy, migration support, and biodiversity, but also the oil and the coal industry. This framing narrative begs a lot of questions: who purchases Australia? And why, if the country is entirely uninhabitable? And why does Australia have no say in what the money will be spent on? As is the case with many simulation games, players are not expected to question the simulation’s rules or premise, and it is unclear how Fortitude might respond to players who do.

Larps that simulate climate politics draw on the design conventions of serious (simulation) games. In her history of serious games Jennifer Light explains that, after their initial success in military and business training in the postwar era, serious games increasingly started being mobilized in participatory urban planning projects and in other contexts that involved lay people. Among other things, they introduced these audiences to the principles of systems thinking. According to Light, this held great potential for governors because “In a climate where dropping out of or sabotaging ‘the system’ was the route to liberation preferred by some members of society, the appeal of systems thinking beyond its scientific and technical associations was its simultaneous concern with communication and control” (370). Serious games give players a sense of agency and control, while limiting interaction to parameters set by the design. Fortitude too empowers players to debate what should be prioritized in a global climate action plan, but it does not seem prepared to facilitate a more fundamental debate about the way this plan is financed or enacted.

Moreover, the success of simulation games often depends on a certain a kind of interaction, or ‘player spirit.’ For example as Lundgren and Loar argue a game of CLUG (the Community Land Use Game) without the competitive ‘spirit of capitalism’ fails to simulate processes of urban growth accurately. Similarly, there are serious games in which a kind of objective technocratic anarchism is assumed to prevail. Buckminster Fuller’s ‘World Game,’ conceived in 1964, pointedly did not assign players countries to represent, but rather expected them to solve the world’s social, political, and environmental problems through the redistribution and efficient deployment of the world’s wealth and resources, from a position of assumed (and, I dare say, impossible) objectivity.

In Nordic larp, the tacit spirit of ‘larp democracy’ often prevails, which means that in accordance with the values of democracy and inclusion promoted in the Nordic countries, players –– especially those who hail from those countries –– often aim to resolve conflict by finding a compromise that appeases all parties. This means that it becomes crucial to consider carefully what actors or stakeholders are included in simulations, since their inclusion will likely influence the political consensus achieved in the game. Consequently, it makes me a little nervous that Fortitude includes petro-states in its roster of countries/characters, and that it adds the coal and oil industry as possible beneficiaries of the climate fund. In contrast, the larp does not give the same level of representation to, for example, indigenous people, or the new Australian diaspora consisting of climate refugees. Climate politics involves more than just building consensus between parties at opposite ends of the table, it about reconsidering who is invited to sit there at all.

There are other larps that dwell on this aspect of climate politics more emphatically. Forecasting Landscape (2022), designed by Shahrzad Malekian and Maïna Joner, features a cast of human and nonhuman actors who have to figure out how to respond to local challenges like natural disasters, bad weather, industrial pollution, and sketchy development projects. In doing so, the larp brings non-human stakes and interests to the table, opening up the kinds of interventions and solutions imaginable to the environmental crisis.

The game is run by a facilitator who describes the challenges, and responds to the ways in which the players have chosen to deal with them by skipping twenty years into the future, and narrating its ramifications. When I played a version of the game set in Oslo, we had to respond to the government’s recent decision to kill Freya the Walrus, a wild animal who had made herself a little too comfortable in the Oslo Fjord, damaging boats, and endangering those reckless enough to provoke her. Since I was cast in the role of ‘Local Political Leaders,’ I had to manage the outrage born down on me by my fellow players who represented (among others) the city’s animal inhabitants, both wild and domesticated. In another version of the game that was localized for Jæren, the province that houses Norway’s oil capital Stavanger, I played an oil platform. Trying to speak from the interests and desires of a piece of infrastructure made me think about their long-term use, encouraging me to imagine alternative functions for oil platforms in a post-oil future. In short, the larp explores what Bruno Latour called the “Parliament of Things,” taking seriously political representation for nonhuman beings.

A final example illustrates how larp can be used to amplify the urgency behind environmental issues. Baltic Warriors was a series of larps organized in Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Poland, Denmark and Russia. The larps staged civil and political summits addressing the problem of eutrophication in the Baltic Sea, while an epidemic of zombie Vikings spawning from nearby “dead zones” provided a sense of threat and urgency to the discussion. The zombie Vikings who threatened to raid the summits were played by larpers expertly made-up and costumed. They made the problem of algal bloom and the consequent de-oxygenation of water bodies both concrete and menacing, while the origins of the issue (agricultural and industrial pollution, rising atmospheric CO2) were addressed in the debates. The larp successfully invited local politicians to participate, arguing that “after you have run for your life to escape from eutrophication, you are more likely to take it seriously in parliament.”

Pseudo-Fictional Workshops

Another category of climate larp stages pseudo-fictional workshops. Larps like these might ask participants to play (versions of) themselves instead of fictional characters, and they often observe unity of time and place. Since they offer explicit instruction throughout, and only require minimal role-playing, ‘workshop larps’ are accessible to inexperienced players, making them easy to program at festivals and in spaces that are not larp-related but which might still draw participants concerned with climate change.

For example, Cyborg Gaia Allies is a larp by Lina Persson and Josephine Rydberg, played at Stockholm Scenario Festival in 2021. It stages a workshop in which players, who have received a mysterious call from a better, more sustainable future, engage in exercises that sensitize them to what they can do to make that future come about. The larp uses a material object owned by the player that is used over the course of the game and ‘charged’ with energy. This object is then taken home afterwards, where its purpose seems to be to emanate or infect—to use the language of the larp itself—the real world with the energy and commitment generated during play. In this way the larp strategically mobilizes what larpers call ‘bleed’—which is when emotions and connections linger on after the larp has finished. As Chloé Germaine explains, the magic circle that purports to delineate play in larps can be understood as a kind of occult technology, generated through material means, using animate and inanimate actors. Props like the ones used in Cyborg Gaia Allies create “a technological magic circle opening and closing boundaries between worlds,” or in the case of the larps discussed in this section, between different times.

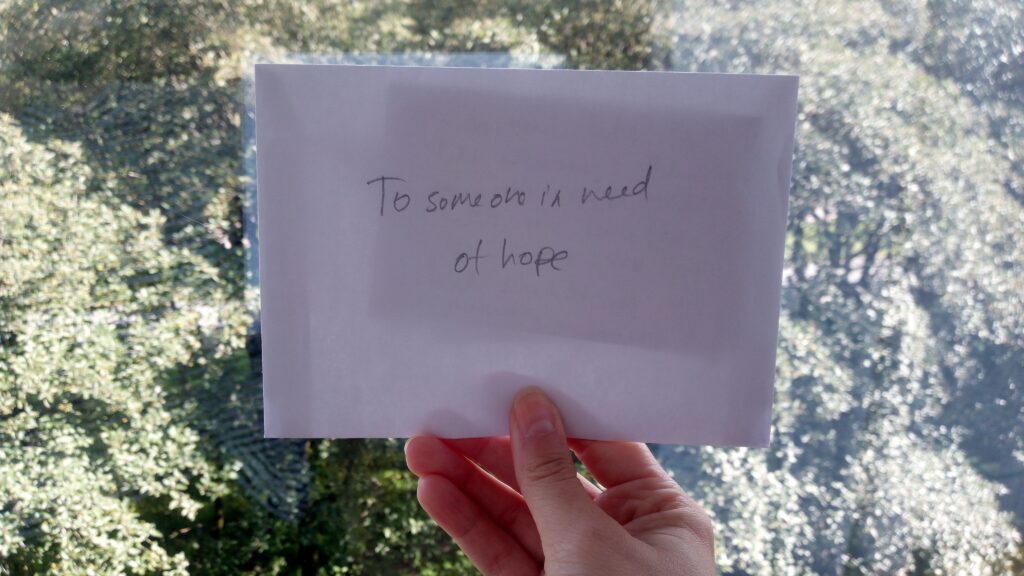

A Ceremony for Hope by Nina Lund Westerdahl and Thibault Schiemann—mentioned at the start—offers another example. Its greatest achievement is that the larp can be run without the facilitators present, which creates a feeling of self-organization and a horizontal social dynamic that recalls the workings of many activist meetings. Reading aloud the game’s script takes you smoothly from one step to the next, through a brief set-up, a 1,5 hour ceremony comprising of four separate rituals at different ‘stations,’ and a debrief. During the set-up, the larp asks you to fill in a sheet in which you reflect on the ways the climate crisis stands to impact your dreams and aspirations in life. You list some events that you wish to happen, as well as your greatest fears regarding the climate crisis. Based on some dice rolls, these hopes and fears do, or do not come to pass by the time 2064 swings around, which is the time when the ceremony is imagined to unfold. The ceremony consists of a four-part ritual that takes place at four different stations, laid out and decorated in a large space. In smaller groups of 4-5 people players cycle through each station so that everyone has the chance to practice each part of the ritual. These parts include: 1) tying knots in a rope for each thing you are grateful for, 2) dropping stones into a bowl of water listing all the concerns and fears you carry 3) speaking to your younger self through a mirror, 3) and writing a letter to someone in need of hope. The ritual is concluded by coming together at the center of the space, distributing the letters randomly among the players, and reading aloud a couple of words to share collectively.

Though it was not made explicit, those in the know will realize immediately that the larp is inspired by ‘The Work that Reconnects,’ a workshop designed by the Buddhist practitioner and deep ecologist Joanna Macy in the 1970s. The Work that Reconnects traces an emotional journey, often figured as a spiral, through four successive stages: Coming from Gratitude, Honoring our Pain for the World, Seeing with New Eyes and Going Forth. It is meant to unblock repressed feelings of grief about the climate crisis in order to catalyze a deeper connection and stronger sense of commitment to the Earth. The Work that Reconnects can be performed in many ways, though ideally it is done together, in a group, over the course of a day or more. Clearly, a larp is a good vehicle for it since larpers often seek out collective, emotionally charged experiences.

But there are also differences between larp and scripted emotional journeys like the one outlined by The Work that Reconnects. At its core, I think larp is about co-creation. A Ceremony for Hope, in contrast, describes an oddly individual experience, an exercise in parallel play. There were no real opportunities to play together. When I played the larp, the other participants were there for me—but only to bear witness, and to offer the support of their presence, not really to engage in dialogue or collaborative storytelling. The larp includes no clear method to echo, to relate, to question, to provoke or to disagree. Consequently, I felt quite alone going through the four different rituals.

In addition to feeling lonely, I also felt vulnerable having to play myself. In this respect, the larp proved to be quite a blunt tool, asking about hopes, fears, and grief in such a general way as to elicit feelings that had nothing to do with the climate crisis but which sprung from much more mundane, if equally devastating news like my mother’s (then) recent diagnosis with cancer. In a workshop or larp that aims to meticulously guide players through different stages of a scripted emotional journey, to feel differently, or to doubt the validity of your feelings within the given framework is incredibly alienating. It makes you feel like a fraud, especially when there are no opportunities to voice these doubts and to discuss them with others.

In her book Bad Environmentalism Nicole Seymour interrogates the narrow emotional spectrum of “affects and sensibilities typically associated with environmentalism,” which include—chiefly—seriousness, sentimentality, guilt and grief. These affects have come to dominate what are considered accepted responses to the environmental crisis, at the cost of what Seymour calls “bad affects,” like ambivalence, irony, and irreverence (including in my case a kind of relativism, an acute feeling of the difference between personal and collective grief). These bad affects are less proximal, or sincere, and they preserve some sense of critical distance between the sensing, thinking subject, and environmental discourse. Such critical distance is necessary to dispel the harmful purity politics that are all too quickly adopted in the name of environmentalism, and to expose the movement’s exclusionary assumptions, specifically regarding race, class, gender, sexuality, and ability.

Black Box Experiences

Black box larps are designed to be played in minimalist spaces where the atmosphere can easily be changed through lighting, audio, props or other kinds of stagecraft. Nordic larp festivals like Blackbox Copenhagen and Grenselandet traditionally feature these kinds of games because they often last no more than a couple of hours, require minimal set-up, and demand no preparation from their players. The first larp I ever played was a 2020 blackbox larp called The Ark, designed by Martin Nielsen and Karete Jacobsen Meland. It introduced me to what I have come to learn are typical elements in blackbox larp: an initial workshop phase that gradually and thoroughly prepares players for the experience to come, a repeating sequence of steps or instructions that players can fall back on without the facilitator’s constant guidance, the use of lighting and audio to create heightened states of emotion, and recourse to nonverbal elements to inspire deeply personal processes of interpretation and narrativization.

In addition to being my first exposure to Nordic larp, The Ark was also my first environmental larp, because it encouraged its players to reflect on the extinction of animal species caused by human impact. In The Ark, all participants played ‘endlings,’ or the last individuals of a species, travelling aboard a ship together, reflecting on their hope for the future, their family memories, and their ideas about kinship and death. For me, the larp explored questions of anthropomorphism and found family. In comparison to larps formatted like workshops or diplomatic simulations, Blackbox experiences often feel less scripted, more spontaneous, more unpredictable, and more open to interpretation.

Case in point, From the Ashes: The Last Climate Crisis (2023) is a larp by Frederikke Sofie Bech Høyer. The larp requires that players be split into three groups representing three generations: grandparents, parents, and children. Each group has a different relationship to the climate collapse that pre-dates the events of the larp. Grandparents have lived through the climate catastrophe and witnessed the fall of civilization personally. Parents are those who were only small when it happened; they can barely remember the details. And the children have no experience of it at all. The three groups then cycle through four different scenes, named after the four seasons. In the spring a new generation of children is born. This scene is played nonverbally. The parents and grandparents welcome the children and help them plant a little seed in a planter (which everyone is encouraged to take home with them after the larp). In the summer scene, the community decides either to dream or to remember, telling stories and making drawings that represent the future they wish to build, or the past they remember. In the fall, the community shares a meal, taking care not to deplete the stores and making sure the children eat first. The winter brings another nonverbal scene with the older generation dying and the parents and children saying goodbye. In the next round, the grandparents are reborn as children, and all the other players are aged up. This cycle is repeated three times.

In the playthrough of the larp that I witnessed, the bond established between the three generations was nurturing and wholesome. Play was heartfelt, at times sad, but also sometimes light and jokey, such as when the grandparents struggled to explain what snow was to a generation of curious children, or when a plastic wrapper of a candy bar during a shared meal solicited ambivalent responses: lamentations at the toxicity of plastic waste, and rhapsodic responses to the delightful chocolate inside. In other words, the larp demonstrated a broader emotional bandwidth than, for example, A Ceremony for Hope because it was easier for players to help set the tone through dialogue and improvisation.

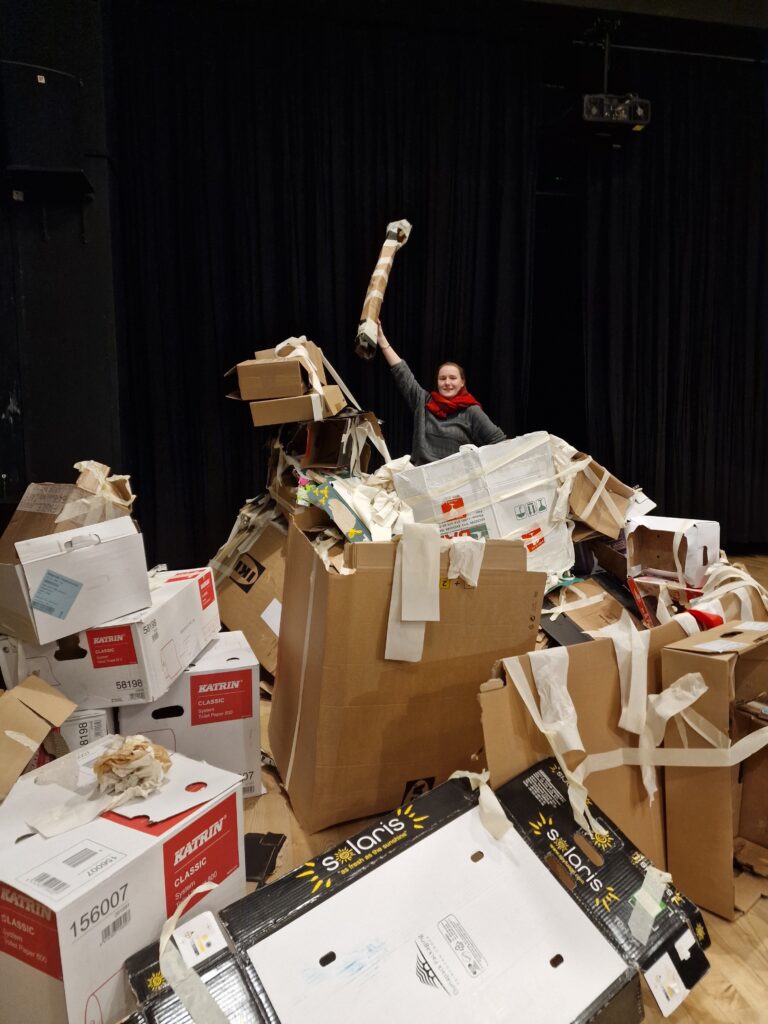

Another larp that was equal parts sad and silly was Alex Brown’s Spillover. Spillover is a nonverbal larp that takes its name from the process of zoonotic contagion, which happens when pathogens jump the species boundary between humans and other animals, such as when, in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus jumped from bats to humans. Spillover effectively demonstrates how the conditions arise for this phenomenon occur, which involves deforestation, habitat destruction, and the increasing overlap between human centers of habitation, and wildlife areas. In Spillover, participants alternate between playing human and bat characters; the latter are blindfolded. Initially the two groups occupy different areas of the room, and engage in different activities. While the humans compete and collaborate with each other to build towers and structures from cardboard (sourced locally, by digging through bins in Copenhagen), the bats slowly navigate a forest of toilet paper, suspended from the ceiling. Bats rely on the texture of the paper to identify the edges of the forest, within which they are safe, in addition, they make ‘i’ noises to signal their presence to the other bats. The humans are allowed to communicate with the full range of vowels, though I often fell back on the ‘oo’s and ‘aa’s of primate communication.

The result is a cacophony of noise, one that swells every time the human players clash over territory and resources, squabbling and bargaining over cardboard and masking tape. Over the course of the larp, navigating the space as a bat becomes increasingly difficult not only because it was hard to locate your fellow bats in the din of noise, but because the forest of toilet paper was slowly dismantled, and not just because the bats were using it for food or nesting materials. In fact the humans were also harvesting the paper to decorate their cardboard fortresses. Consequently, the blind bats strayed further and further into human territory, colliding with cardboard towers, and bringing everything crashing down.

The narrative arc in Spillover is a tragic one that traces the gradual degradation of a habitat, although in play there were also moments of joy and giddiness due to the challenge of moving while blindfolded, and the absurdity of communicating using just vowels. The tragedy creeps up on you though, helped along by larp’s audio design, which relies on the score of the film Koyaanisqatsi (1983), named after the Hopi word for ‘life out of balance.’ This soundtrack, composed by Philip Glass, ends with a piece that features mournful organ music. It set the tone for the larp’s final movement, during which the bats were reduced to two lonesome figures squeaking hoarsely, aimlessly wandering the space, in search of paper that was no longer available, hoarded by the humans and fiercely defended. The humans had constructed one massive metropolis, with some players expelled to the lower regions of the fort while others held sway in the upper reaches.

My own larp, Leviathan (2023) attempts to trace an equally gradual environmental transformation, albeit using a slightly more fantastical premise. The larp is about people who live on the back of a gigantic beast that is moving through an immense ocean. As it moves, it dips and surfaces to a rhythm that nobody has yet been able to predict. When the beast dives deeper the tide rises and the people’s land shrinks; but when it surfaces again the land is exposed, fertilized and irrigated, encrusted with minerals and vegetation that the people can live on. The retreating tide also reveals surprises, new opportunities, omens, and possible threats. In the game, this tidal dynamic is represented by dimming the lights and playing the sound of a thunder storm that is passing over, during which the players have to seek shelter in make-shift tents, suspended from the ceiling, for which I used sheets of plastic and mosquito nets.

While Leviathan does not explicitly engage with the climate crisis, it does broach themes like unpredictable, dangerous weather, as well as a creeping sense of estrangement regarding the environment. This inability to fully recognize once familiar places because of changing weather patterns, ecological degradation, or biodiversity loss is becoming a more common experience as the climate crisis intensifies. There is a lot of literature that describes this experience and much of it belongs to genre fiction, like sci-fi. More recently, the (sub-)genre of weird fiction has started tackling what might appropriately be called “global weirding,” which describes the strange, the uncanny, the inexplicable, and the sometimes horrifying ways in which the environmental crisis manifests in different locales. Leviathan too seeks to foster a kind of wet, watery, weirdness by staging a delicate relationship between the people, and their living, breathing, (scheming?) world.

Design-wise, the larp covers some of the same ground as From the Ashes by staging an intergenerational dynamic. However, whereas in the latter the relationship between the young and the old was imbued with love and care, in Leviathan it a potential source of conflict. At the start of the larp, the players are divided into younglings and elders, and the groups get briefed separately. The elders are given a worksheet that helps them quickly generate a history of the people, using multiple-choice questions like “where did you come from?” “who was the first of your people?” and “what is under the ocean?” Meanwhile, the younglings are told that their role is to ask questions, both banal and profound. When the two groups are reunited at the start of the larp the younglings immediately start to question the habits and practices of the people; whereas the elders fall into the role of having to explain why the world is the way it is based on the mythology they generated.

Moreover, the elders are randomly assigned certain attitudes, for example “you think of the beast as a guardian,” or “you think the beast bears will drown you,” or “you think the beast does not exist.” The younglings have not made up their minds yet, but are invited to do so over the course of play. This decision might be influenced by the elders, but it might also be swayed by the strange occurrences that the players are peppered with (‘tidal treasures’ that are balled up pieces of paper with event prompts in them). Additionally, there is a bright spotlight at the center of the room, representing a giant pit—or is it the beast’s blowhole? Over the course of play, the spotlight gradually changes color, from green to red, triggering competing interpretations of what it means, and how the people ought to respond. In this way, Leviathan tells the story of a people whose homelands are changing underneath them, necessitating investigation, discussion, adaptation, and even, possibly, migration.

Conclusion

Based on this brief, exploratory study of environmental larp, already it is possible to observe some common themes and design patterns. For example, both From the Ashes and Leviathan engage with intergenerational dynamics which are crucial and increasingly politicized in climate discourse; and both Leviathan and Spillover emphasize processes of gradual environmental change as opposed to more spectacular natural disaster. Anthropomorphism is another trope, used in The Ark as well as in Forecasting Landscape to introduce reflection on nonhuman stakes and interest in the climate crisis. There are also more recent larps, like Other Minds (2023) by Alex Brown and Nina Runa Essendrop that take such species-bending experimentation further, using sensory deprivation (sight) and stimulation (touch, audio) to explore the nonhuman cognition and speculative culture of octopus. Finally, many of the larps discussed in this article make creative use of cheap materials as props or setting elements. Spillover required the sourcing of cardboard boxes, and its forest biome was constructed out of toilet paper, and in Leviathan I used thin, billowy plastic sheets as props and single use rain-ponchos as costumes in an attempt to anchor the mythological tenor of the larp to the contemporary issue of plastic pollution in the ocean. While not as sustainable as cardboard –– bio-film poncho’s were only affordable in bulk –– the costumes did lead the players to report feeling increasingly clammy and hot over the course of play. Though I did not anticipate this result, I am pleased with it, since it obviously serves as a visceral reminder of a warming world.

To conclude, I want to acknowledge that the environmental, or eco-critical dimension that I have explored here is confined to matters of creative game-design. There are other dimensions that remain to be explored, especially those concerning the sustainability of larp production, consumption, and the broader culture of participation that supports it. As Alex Brown explains, there is an elephant in the room: “aviation emissions in international larp.” Since the practice remains quite niche, big productions, or blockbuster larps, are only possible because they can depend on the support and participation from people who (often) have to fly in from all over. The same goes for the international festivals that feature the larps I have discussed in this article. With sustainability so high on the agenda among many larp organizers, this has of course become a point of focus. The organizers of the Nordic larp conference Knutepunkt 2023 urged people to take sustainability into account when booking their travel, and they also attempted (unsuccessfully) to eliminate meat from the menu. While these are important steps that can be taken to reduce the impact of international larp events, I also agree with Brown that a robust, lively local scene, and more experimentation with digital larp using platforms like Discord and Zoom, would relieve some of the pressure larpers feel to attend faraway events and festivals, thus reducing air travel emissions.

–

Featured image is “Leviathan” by Keith Mason CC BY 2.0 @Flickr

__

Laura op de Beke obtained her PhD from Oslo University in 2023. Her doctoral thesis “Anthropocene Temporalities in Videogames” asks how videogames give us access to conceptions and experiences of temporality in an age deeply impacted by climate change and environmental crisis. Laura is also an active contributor to the Nordic larp scene. She was the PI of the project “Playing With Deep Time,” which looked at game design practices in TTRPGs and larps that help create encounters with deep time. The deep-time larp that she developed for this project was nominated for the IndieCade Live Action Award (2022). You can keep up with her work at www.lauraopdebeke.com.