In opening her account of the rise of game live streaming, Watch Me Play, T.L. Taylor recalls stumbling upon a live feed of a Star Craft 2 computer game tournament being broadcast from Paris over the Internet. She was struck, she said, by the myriad forms of “communication and presence among broadcasters and audience, both on-site at the venue and distributed throughout the network.” Taylor describes experiencing a powerful and resonant feeling of watching the event, not alone in her living room, but “alongside thousands of others in real time.” Ultimately, she concludes, game livestreaming as a medium both imitates and challenges television, its predecessor form. “While the devices and conventions may change,” she says, “the televisual is going as strong as ever.” “A more productive way of thinking about media transformations,” she continues, “is to see that there are circuits between traditional and new media spheres. People are still watching television and consuming traditional content alongside user-produced YouTube videos and Twitch’s game live streaming channels. The media mix is the key. Content, producers, and audiences flow across a range of devices, platforms, and genres.”

Making sense of these flows has occupied the attention of game studies scholars who are interested in the way that economic and social forces shape the experience of the ludic in modern life. For example, media scholar Henry Jenkins sees “convergence thinking” as a kind of “collective intelligence” occurring “within the brains of individual consumers and through their social interactions with others.” Convergence culture emerges, he says, from media concentration under corporate control in the presence of “digitally empowered consumers” influencing the forms and functions of participatory popular culture. It “is both a top-down corporate-driven process and a bottom-up consumer-driven process.” Similarly, rhetorician Ken S. McAllister describes a computer game complex in which the production, distribution, and consumption of games operates as an economic, cultural, psychophysiological, and instructional mass medium simultaneously, and develops a “grammar of gamework” to explore the dialectical tensions that are embedded within the rhetorical events comprising computer game experience—the game as art, work, labor (of love), and play. Along with his colleague Judd Ruggill, McAllister continues this exploration by pointing to the entanglement of ideas about work with those about art, play, and criticism in the context of computer games, regarding the whole complex as redolent of alchemy—a term that is “marked by combination, distillation, and ambiguity” and which connotes “an alloy (or is it a brew?) so dense as to be impenetrable, so fluid it cannot be held.”

Taylor’s report of her experience is thus striking not for its complete novelty, but instead for how it describes an almost alchemical reproduction of the phenomenology of fandom in a new configuration, at once both familiar and a little strange. How different, after all, is the feeling Taylor reports from that of the football enthusiast in the stadium—or at home watching the game? What has changed is the sort of game the spectators are watching, and the communication modes those spectators employ. This reproduction of the recognizable experience of “watching the game” in way that involves new media forms, both as “message” (or content, in this case the play of the computer game Star Craft 2) and as medium (that is, Internet live stream), amounts to what media scholar Marshall McLuhan referred to as retrieval: the evocation of an older technology by a newer one.

It is true that Marshall McLuhan’s intellectual legacy mixes uneasily with his status as a media darling and pop culture celebrity of the mid-to-late twentieth century. “McLuhan’s playful style, his love of puns and aphorisms and one-liners, [and] his refusal to play by the rules of academia enraged that class of individual the poet T. S Eliot described as ‘the mild-mannered man safely entrenched behind his typewriter,’” according to a biographer writing in the Toronto Star on the centenary of McLuhan’s birth. “McLuhan’s embrace of celebrity confirmed suspicions among many of his colleagues that he was little more than a charlatan,” the retrospective went on, and “in fairness to these critics, McLuhan, who had experienced long years of penny-pinching in support of his wife and six children on a professor’s salary, frankly admitted he wanted to cash in on his fame while it lasted.”

But since McLuhan’s death in 1980, a discipline called media ecology has emerged that continues to be inspired by and in dialogue with McLuhan’s scholarship. Media ecology “is the study of media environments,” the founding president of the scholarly Media Ecology Association explains, informed by “the idea that technology and techniques, modes of information and codes of communication play a leading role in human affairs.” The field takes its name from a concept introduced by Neil Postman and traces its forebears through scholars such as Harold Innis, Walter Ong, and Lewis Mumford, sometimes going as far back as Plato’s Phaedrus, in which the relative merits of writing versus speech as modes of communication are discussed. But Marshall McLuhan’s work remains foundational to media ecology as a field, even if criticizing or correcting particular observations, speculations, or “probes” essayed by McLuhan is a chief part of media ecological practice.

For game studies scholars, the emergence of new media content and new media forms in the Internet era arguably renews the relevance of McLuhan’s gnomic but intriguing prognostications about the impact of mass media on human consciousness. “The revival of McLuhan,” Marchand says, “is no mystery. His insights about the effect of electronic technology in particular—the re-tribalization of the young, the vanishing of such concepts as privacy, the weakening of personal identity, the tendency among users of the media to become what McLuhan called ‘discarnate,’ or almost literally bodiless—these insights are more pertinent than ever in the world of Facebook and iPhones. His writings from the sixties and seventies seem to apply more to our own era then they do to his.” For example, in 1962 McLuhan wrote that “a computer as a research and communication instrument could enhance [information] retrieval, obsolesce mass library organization, retrieve the individual’s encyclopedic function, and flip it into a private line to speedily tailored data of a saleable kind.” It is hard to read this sentence without recognizing it as a prescient description of the Internet era.

However, as Coupland points out, “learning McLuhan is like learning a new language, and about as many McLuhan scholars out there speak McLuhan as do, say, Frisian or pre-1968 COBOL . . . There exists little self-apprehended grasp of the man’s thinking,” even though many scholars suspect that “there’s something about Marshall that is original and new.” However, Coupland warns, “getting into Marshall is, for most people, like visiting Antarctica. You have to have time, patience, endurance, means, and stubbornness to do so, and once you’re there, you’re unsure of just what you will find.”

Thus, this essay seeks to dip lightly into the media ecological concepts offered by McLuhan in order to make sense of a ludic new media form, in order to see whether the insights they produce are of value or interest. Before describing the specific site at which this exploration will take place, however, it will be worthwhile to outline a little of McLuhan’s thinking.

The Laws of Media

McLuhan’s famous aphorism, “the medium is the message,” is the heart of his thinking. It threw his audiences for a loop, however. During a question-and-answer period following a lecture in Australia in 1977, McLuhan responded to an audience member:

Q. If the medium is the message, and it doesn’t matter what we say on TV, then why are we all here tonight, and why am I asking this question?

[Laughter]

A. I didn’t—I didn’t say that it didn’t matter what you said on TV. I said that effect of TV, the message, is quite independent of the program. That is, there’s a huge technology involved in TV which surrounds you physically, and the effect of that huge environment, on you personally, is vast. The effect of the program is incidental.

Earlier, the moderator of the session had asked a similar question about the implications of the phrase, “the medium is the message,” wondering if it left any room for the criticism of individual programs. McLuhan’s answering analogy tries to make clear that the distinction he was drawing was between the systematic structuring of human experience on the one hand and the delivery of content on the other.

A. It doesn’t much matter what you say on the telephone. The telephone as a service is a huge environment, and that is the medium. And the environment affects everybody; what you say on the telephone affects very few. And the same with radio or any other medium. What you print is nothing compared to the effect of the printed word. The printed word sets up a paradigm, a structure of awareness which affects everybody in very, very drastic ways, and it doesn’t very much matter what you print as long as you go on with that form of activity.

In other words, as McLuhan put it elsewhere, “the ‘message’ of any medium or technology is the change of scale or pace or pattern that it introduces into human affairs.” “The effects of technology,” he goes on, “do not occur at the level of opinions or concepts, but alter sense ratios or patterns of perception steadily and without any resistance.”

It seems easy to charge McLuhan with technological determinism, but he is subtler than that. His approach to understanding media is presented in fullest form in a book called The Laws of Media, prepared with the aid of his son and published posthumously. Concerned with the way that technologies in general serve as expressive media, it is at root phenomenological, serving to organize diverse arrays of meaning associated with a particular “tool,” understood very broadly. “We learned,” Eric McLuhan writes, “that [the laws of media] applied to more than what is conventionally called media: they were applicable to the products of all human endeavor, and also to the endeavor itself! . . . We found that everything that man [sic] makes and does, every procedure, every style, every artifact, every poem, song, painting, gimmick, gadget, theory, technology—every product of human effort—manifested the same four dimensions.”

The McLuhans call these four dimensions or “laws” of media a technological tetrad that describes reconfigured perceptions of “figure” and “ground” on the part of the user. “In tetrad form,” they say, “the artifact is seen to be . . . an active logos . . . of the human mind or body that transforms the user and his [or her] ground.” More specifically, new tools (1) enhance by augmenting some existing human capability or enabling a new one, (2) obsolesce or render obsolete some hitherto extant technologies, (3) retrieve, revive, or evoke other previously obsolescent technologies, and (4) when pushed to their limits (but still used exactly as intended), “flip” or reverse into a dysfunctional form. Thus, the photocopier as artifact when examined through the lens of McLuhan’s tetrad (1) enhances “the speed of the printing press,” (2) antiquates “the assembly-line book,” (3) retrieves “the oral tradition”—the McLuhans adduce the Pentagon Papers in support of this point; they could have pointed to Soviet samizdat—and (4) dissolves the reading public, since the reader is now a publisher. The cigarette, they say, enhances “calm and poise,” obsolesces awkwardness and loneliness, retrieves ritual and group security, and reverses into nervousness and addiction. Slang, they observe, enhances the novelty of mental concepts or percepts, obsolesces “conventional vagueness,” retrieves “unconventional feeling,” and reverses at its extreme into cliché or “conventional concept.”

The tetrad is perhaps best understood as a heuristic or organizing device for thinking about the ways that expressive tools, communicative techniques, or information-bearing constructs reconfigure human experience, allowing specific functions to be attributed along each dimension of effect—within each quadrant, that is to say, of the tetrad. The McLuhans’ method seems to have been impressionistic rather than wholly systematic, but it seems clear that any media ecologist seeking to employ McLuhan’s typology of media functions must employ well-grounded historical or linguistic evidence and well-attested accounts of lived experience. And, as Henry Jenkins observes, while “a medium’s content may shift . . . its audience may change . . . and its social status may rise or fall . . . once a medium establishes itself as satisfying some core human demand, it continues to function within the larger system of communication options.”

Having laid this groundwork, a useful initial exercise is its application to the medium of the role-playing game. This serves to provide a baseline or, in McLuhan’s terms, the ground or context against which Actual Play will stand as figure or focal point.

The TRPG as Medium

It seems common within game studies scholarship to regard tabletop RPGs as having been obviated or eclipsed by the arrival of computer games. After listing a handful of notable TRPGs, one recent introduction to the field of game studies observes that it is “no coincidence” that in their list “the most recent truly noteworthy tabletop RPG”—referring to Vampire: The Masquerade (White Wolf 1991)—“is over two decades old.”. And “the Dungeons and Dragons genre,” game studies scholar Espen Aarseth (1997) writes, “might be regarded as an oral cybertext, the oral predecessor to computerized, written adventure games.”

The teleological implications of this perspective are probably best avoided; Michael J. Tresca invokes media richness theory—an approach that categorizes media according the degree to which they permit cues and feedback to be sent and received along multiple channels in a personalized way using natural language—to suggest that particular forms of role-playing may be more appropriately facilitated by being mediated in different ways.

From McLuhan’s perspective, however, a medium or technology can be seen as the historical instantiation of a particular logos or way of seeing or thinking about the world. This instantiation makes certain elements more salient than before, and relegates others to the background—at least as far as a particular subject position is concerned; from other positions, the view may be very different. How else, after all, can McLuhan’s interpretation of the brothel as a medium, which enhances “the sex act as package deal” and threatens to reverse into “hallucination for lonely hearts” be read, except as a masculine or at least “demand-side” understanding?

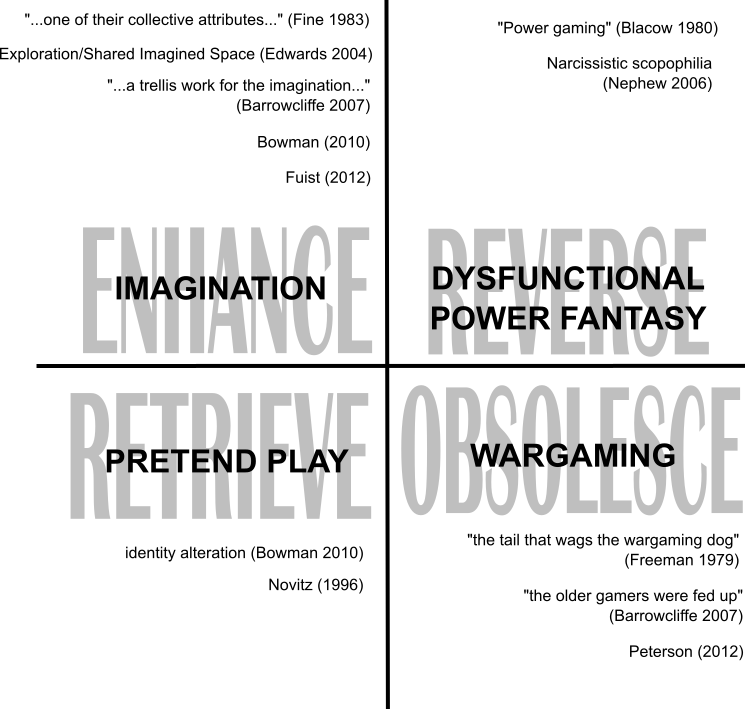

To understand tabletop role-playing games from this perspective, therefore, it is necessary to keep in mind the subject position of the TRPG player, which changes over time as the cultural logic of TRPGs is articulated to a greater extent. Nonetheless, it is possible to see the media functions of the TRPG as enhancing imagination, obsolescing the wargame, retrieving pretend play, and reversing into dysfunctional power fantasy (see Figure 1).

Enhance Imagination

Gary Alan Fine’s seminal 1983 ethnography of fantasy role-playing games presents imagination as a central characteristic of role-players. Players shared the belief that imagination, as “one of their collective attributes”, was necessary to play RPGs, and served to differentiate them from “the average Joe on the street,” whose normative commitments were so numerous and demanding as to leave “no time, energy, or inclination for active fantasy.” A woman interviewed at the 1985 GenCon gaming convention told a New York Times reporter that “gamers are articulate people with superior imagination.” And a much more recent account of player motivations still identifies “imaginative creativity” as a fundamental conceptual category describing how players talk about the experience of play. Similarly, in his memoir of playing D&D as a teenage boy in England, Mark Barrowcliffe (2007) says that TRPGs “provided a trellis work for the imagination to climb on and thrive. Unsupported, your daydreams can wither; backed up by rules, pictures, model figures, and the input of others, there’s no end to the amount of brain space they can consume.”

Other descriptions of play reinforce the point that imagination is a central element of role-playing gaming. Analog games scholar Sarah Lynne Bowman notes that RPGs allow players to develop and practice interpersonal and cognitive problem-solving skills within fantasy scenarios imaginatively constructed as puzzles, tactical challenges, or social negotiations. T.N. Fuist similarly points to the exploration of imagined worlds and alternate selves as a key part of the role-playing experience.

Imaginative “exploration” was also seen as the fundamental purpose of TRPG play by the theorists at The Forge, an online discussion site for TRPG design, publication, and play active from 2001 to 2012. There, exploration was defined as “the imagination of fictional events, established through communicating among one another.” This was regarded as nearly synonymous with the “Shared Imagined Space” (SIS) created by TRPG play (Edwards 2004).

Obsolesce Wargaming

Originating among enthusiasts for military miniatures and boardgames, TRPGs were almost immediately a source of disruption within that community. Barrowcliffe depicts “older tabletop gamers who played with model soldiers . . . becoming sick of the level of whooping and shouting that went on at the average D&D game.” Jon Peterson’s history of the origins of Dungeons & Dragons describes some wargamers responding with enthusiasm and others with suspicion; he quotes wargame designer Lewis Pulsipher as opining that, “It is not a game for someone who cannot get away from the ‘competition’ idea,” and noting that “non-wargamers are often attracted to it as well as veteran gamers.” The popularity of D&D among wargamers threatened to supplant other games in the wargaming clubs of the late 1970s, such that game reviewer Jon Freeman could explain to a general readership that “a quarter of a million Dungeons & Dragons players threatens to make FRP games the tail that wags the war-gaming dog.” The key element of this change, as Peterson (2012) describes it, was the shift in player perspective from commanding armies to controlling only a single figure with whom the player could identify.

Retrieve Pretend-Play

Though Bowman sees the development of problem-solving skills and the ritual enactment of community as functions of role-playing games, more central to her understanding of why people play is the function of “identity alteration,” in which players adopt alternative social roles and personality traits for themselves, trying them out in a way that mirrored the role of pretend play in child development. Brian Sutton-Smith notes that there are ambiguities to be found in the discourse of play with respect to those functions “that apply to children and those suitable for adults.”

Philosopher David Novitz was puzzled about why adolescent males like his son were willing to devote a considerable amount of time, remember a vast number of rules, keep in mind all of the complex, emotionally charged details of the game, and indeed to “value such games, derive considerable satisfaction from them, and play them almost incessantly.” He thought it might have something to do with the benefits he saw associated with that play, which he saw as emerging in response to an unparalleled adult intrusion into the lives of boys, as well-meaning parents sought to remedy the defects of masculinist culture by condemning the toys, games, novels, and movies that had hitherto been standard male adolescent fare—but without providing much in the way of emotionally satisfying alternatives.

One effect of all of this, I would speculate, was to encourage boys to look elsewhere not just for their play and their entertainment, but also for the freedom, support, and approval that were not always available to them in the classroom, at home, or in the media. What they developed was a space beyond the reach of adult condemnation; a space in which the growing adolescent desire for freedom and control would in some measure be met. . . Still more, because these games enabled boys to share their imaginings, to build on, elaborate, and enjoy one another’s fantasies, they became a cooperative endeavor that helped legitimate one another’s desires and views of the world, and encouraged solidarity among a group who had contrived, for a time at least during the waking day, to be immune from the intrusive directives of their parents and their community.

It is possible, of course, to go further afield and to regard this sort of play as a retrieval of what rhetorician Thomas Lessl calls the “bardic voice,” a countervailing force in the face of an intrusive didactic presence that operates “as a socializing agency of institutional culture.” In contrast, “when bards talk,” Lessl says, “it is our own voice that we hear, the faint murmuring of a collective consciousness amplified in poetic utterances and often recognizable as myth.” But the important point is that this sort of pretend play, often regarded as the province of childhood, arguably serves an important ritual function related to identity that is often disregarded.

Reverse into Dysfunctional Power Fantasy

The presence of younger players in the gaming groups of the late 1970s and early 1980s was often cause for charges of immaturity directed at “power gamers” who played in order to accrue more and more loot, magic, and character abilities. To the extent that this amounts to a kind of wish-fulfillment, it permits and even sanctions taboo-violating behavior by explicitly positioning player-characters as “good” within the setting, thus enabling the rationalization of what would otherwise be abhorrent acts. Even Gary Alan Fine seems a little shocked by the casual misogyny of the players he studies, both in and out of the game. Sociologist Michelle Nephew sees this as part of a pattern in which stereotypes of masculine power are emphasized and reinforced while simultaneously empowering male players who are “feminized and desexualized by the dominant culture.” In addition, Nephew says, the representation of female characters by male players often amounts to kind of narcissistic or fetishistic scopophilia; that is, “taking other people as objects [and] subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze,” thereby “taking pleasure in using another person as an object of sexual stimulation.”

“Actual Play” as New Medium

It is in this context, then, that developments in tabletop role-playing games—their continued articulation as a cultural form by cultural agents — can be considered. One recent development is that of what is called Actual Play. The term refers to TRPG sessions performed, recorded, and broadcast to audiences for a variety of reasons. The phenomenon is sufficiently noteworthy to have garnered attention both from within the game community as well as by external observers. According to the Diana Jones Award Committee, “Actual Play shows . . . have done more to popularize roleplaying games than anything since the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, and in a far more positive way. They take RPGs out of the basement and put them on the world stage, showing a global audience exactly how much fun roleplaying games can be when played by talented people who are fully invested in their shared stories.”

An article in the online multimedia platform The Verge attempts to explain the success of the Actual Play phenomenon:

According to Matthew Mercer, a voice actor who has become one of the stars of this scene, thanks to his gig as the dungeon master for the massively popular liveplay series Critical Role, “Role-playing games are just an organic improvised space for storytelling.” Add in the interactivity of a live stream — which typically allows viewers to comment, pose questions, and even affect the course of gameplay — and you get a uniquely addictive viewing experience: part game show, part talk show, part fantasy-adventure serial. “The people who watch the show are instrumental in helping us create the show,” says Anna Prosser Robinson, lead producer for Twitch Studios, founder of the women-focused gaming network Misscliks, and on-screen personality in liveplay shows including Dice, Camera, Action. Prosser Robinson, who got her start in the e-sports world, calls liveplay RPGs a truly collaborative way of storytelling: “People want to be part of telling a story together.”

It is important in making sense of a new medium—particularly in thinking about the unanticipated consequences that reverse its enhancing effect—to establish the point of view from which one proceeds. In this case, in order to gain access to such a perspective, I examined a discussion thread about Critical Role on an online forum for talking about TRPGs, particularly the sort sometimes called story games in order to distinguish them from more “traditional” approaches TRPG play.

In this thread, the original poster (OP) notes that he recently came across Critical Role and that it made him realize that “something is happening in the gaming world.” The existence of online campaigns being watched by millions of fans who in turn create lengthy reviews and commentary that are in turn shared among fans is striking. What, he wonders, does it all mean?

In reading this thread as a source of information about Actual Play in general and Critical Role in particular, I am explicitly attempting to distance myself as an observer of the phenomenon and relying instead on the discourse surrounding it—albeit a discourse that is already somewhat distant from the phenomenon in question, one that has been framed as proceeding from both a sense of surprised relief at the renewed popularity of TRPGs as signified by the immense popularity of a show like Critical Role as well as from a bit of disappointment that the TRPG techniques it seems to showcase and celebrate are relatively traditional. The resulting discussion, comprising 369 comments over a period of 19 months between November 2017 and May 2019, presents a usefully complicated picture of Actual Play. Participants in the discussion lay out divergent views, present different experiences, and challenge each other’s conclusions.

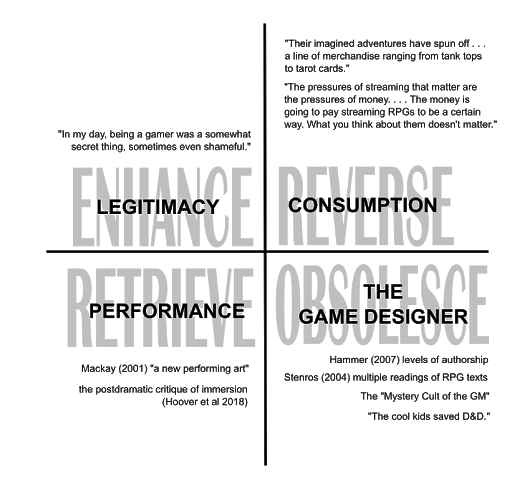

From such a perspective, the role of Actual Play appears to be to enhance the cultural legitimacy of RPGs, obsolesce game design as central concern of TRPG culture, retrieve performance as a key element of play, and threaten to reverse into consumption when taken to an extreme. Figure 2 recapitulates this summary.

Enhance Legitimacy of TRPGs

The hitherto fraught cultural position of TRPGs is given some attention above in the discussion of RPGs as a medium, but it is worth noting that the rise of Actual Play comes in close proximity to something of a rehabilitation. Popular press articles observe with a measure of incredulity that D&D has somehow become “cool” or “cool again,” and a prominent motif in the Story Games forum discussion thread is how the popularity of Critical Role and other Actual Play streams signals the increased legitimacy of TRPGs. “In my [non-gamer] social circles . . . I’m seeing a different attitude,” the OP observes. “In ‘my day’, being a gamer was a somewhat secret thing, sometimes even shameful—you hope to weed out who might be friendly to your weird hobby before revealing that you’re part of it. Newer gamers seem to be proud of the label, and advertise it with paraphernalia of various sorts.” Memoirists like Barrowcliffe and Ethan Gilsdorf also report the discomfort they feel about identifying as gamers.

It is possible, of course, that the causal arrow points in the other direction: that Actual Play programs benefit from a cultural rehabilitation of RPGs in general and Dungeons & Dragons in particular occurring for other reasons. However, at least some evidence suggests the temporal priority of Actual Play. In a New Yorker article describing the “uncanny return” of D&D, the author describes a “pop-up board-game club and café, Brooklyn Strategist . . . where children and their parents could sit down and play games, both classic and obscure, over veggie platters and homemade ginger ale.” Proprietor Jon Freeman, a former clinical psychologist who was interested in using games to help develop children’s cognitive abilities, introduced Dungeons & Dragons into the mix, admittedly at the prompting of a kid who was curious about the game. Then, however, “two popular role-playing shows, ‘The Adventure Zone’ and ‘Critical Role,’ sent Freeman’s older patrons to their knees, begging for more D&D time in the store.” As a result, “Freeman had to hire half a dozen paid Dungeon Masters for the kids and has now begun training volunteer Dungeon Masters to guide adventures for the adults who drop in on Thursdays to fight goblins, trick castle guards, and drink wine.”

Additionally, one poster in the Story Games thread reports that “about half of the people who join my local RPG forum cite Critical Role et al as the reason they want to get into gaming themselves,” even if only very few of them wind up becoming “active players”.

Retrieve Performance

Daniel Mackay wants to understand role-playing games as a new performing art, he says, and this perspective makes up part of a broader multi-disciplinary project of studying RPGs, drawing upon performance studies and ritual studies to understand aspects of RPG play related to its character as embodied interaction, or postdramatic participation, in the awareness of enacting a role. Such perspectives lead to a critique of immersion, a critique that sees immersive RPG play as insufficiently self-aware, since it is capable of suppressing reflexive objectivity in favor of reproducing oppressive social relations, slipping into a voyeuristic and hedonistic pursuit of desirable affective experience.

This is, of course, a criticism of the un-self-consciousness of play itself. As philosopher of language Mikhail Bakhtin observes,

Playing, from the standpoint of the players themselves, does not presuppose any spectator (situated outside their playing) for whom the whole of the event of a life imaged through play would be actually performed; in fact, play images nothing—it merely imagines. The boy who plays a robber chieftain experiences his own life (the life of a robber chieftain) from within himself: he looks through the eyes of a robber chieftain at another boy who is playing a passing traveler; his horizon is that of the robber chieftain he is playing. And the same is true of his fellow players . . . Playing begins really to approach art—namely, dramatic action—only when a new, nonparticipating participant makes his appearance, namely, a spectator who begins to admire the children’s playing from the standpoint of the whole event of a life represented by their playing, a spectator who contemplates this life event in an aesthetically active manner . . . In doing so, he alters the event as it is initially given: the event becomes enriched with a new moment, new in principle—an author/beholder, and, as a result, all other moments of the event are transformed as well, inasmuch as they become part of a new whole: the children playing become heroes, and what we have before us is no longer the event of playing, but the artistic event of drama in its embryonic form.

A number of participants in the Story Games thread credit the quality of the GM and player performances with making Critical Role as successful as it has become. “It’s well-prepared content, delivered with a high level of skill by professional voice actors,” the OP observes in an early follow-up post. Another poster is very impressed with the GM skills shown by the host, Matt Mercer:

Having watched 24 hours of play, I’m comfortable saying that Matt is a great DM. He’s prepared and knowledgeable. He has great on-the-fly judgment. He mostly manages spotlight time well, though I think he cares more about audience interest than player interest. He is great at listening and letting players do their own thing without interference. I envy his ability to handle musical selections for mood while running a game! He is fantastic at describing events and portraying NPCs (even without the voices). I am learning things from watching him.

One consequence of this seems indeed to be to make the game more self-conscious of itself as performance, and to present itself to audiences in that way.

Isn’t it a known fact that a well-run trad GM show is pretty good entertainment? . . . If one accepts that premise, then it stands to reason that adding enough of an audience will fundamentally change that creative equation: now you’re not performing only for a couple of occasionally underappreciative friends, but rather to a big video audience. The job might even pay something. It doesn’t look that different from any television work now, so no reason why it couldn’t work: you just put in the hours to prep good sessions, choose players who can do their parts, and do it. It’s sort of like improvisational theater insofar as the audience is concerned, isn’t it?

“What you wind up with,” the OP reports having read in a Google Plus thread, “is really an improv show built on top of the chassis of an RPG and that also incorporates fan reaction.”

Obsolesce the Game Designer

Jaakko Stenros and Hammer point out in complementary ways that role-playing games are multiplex, such that “each participant produces a reading of the RPG text” while the authorship of those texts occurs at multiple levels, a primary level of setting and system (world building), a secondary one of scenario construction (story building), and a tertiary one of play itself. Hammer’s typology recapitulates the distinctions among game designer, game master (GM), and player. Thus, it seems reasonable to suppose that a shift of attention to performance, and particularly the performance of the GM, would result result in a de-emphasis on game design as a practice and the game designer as the principal author of the role-playing game text.

And this concern does seem to emerge at times within the Story Games thread. Discussing a video of GMing advice about how to handle in-game player-character deaths, Paul_T is disappointed with its relative lack of sophistication. “Not a single mention of game design, fudging, plot immunity, encounter design, anything?” he exclaims. “Can we conceive of functional role-playing where the characters can’t die at random? Might that be a good fit for your group? The listener is led to assume—as the rulebooks state—character death ‘just happens’ in D&D, and it’s entirely unpredictable.” And while other posters were quick to push back, charging Paul_T with overstating the case in a negative fashion, the idea that a “GM mystery cult” was being energized by shows like Critical Role had some traction in the thread. As one thread participant explained, the mystery cult of the GM describes “social attitudes and ideas that people attach to being a GM,” and is “essentially a snide name for the idea that being the GM is somehow special and elevated above the ordinary peons, the players.”

“I just had a vision,” poster David Berg reported after the discussion had carried on in fits and starts for over a year. “Excitingly fun roleplaying has spread across the land. Those game sessions that everyone really wants to be fun but just aren’t, are largely a thing of the past. And all the folks who spent so many years and decades trying to help bring this about, with talk and theory and philosophy and design, are just blinking in bemusement, as the conclusion becomes inescapable. They didn’t save the world. The cool kids did.”

Reverse into Consumption

The success of Actual Play shows like Critical Role can be seen in their transformation into intellectual property that can be monetized in multiple media. “Two years and 114 mammoth episodes,” after Critical Role’s first episode,

“their imagined adventures have spun off a comic book, an art book, and even a line of merchandise ranging from tank tops to tarot cards—all in addition to inspiring countless works of fan-generated art, music, and literature.”

But Henry Jenkins cautions against an unalloyed celebration of this sort of media convergence, since it will produce economic and cultural winners and losers in a way that will be difficult to predict until it well after it has occurred. The issue comes up in the Story Games thread in a post by JDCorley, who argues that the economic logic of streaming will come to conform to that of other media industries:

The pressures of streaming that matter are the pressures of money. Of course D&D will be what is streamed and non-D&D will be increasingly squeezed out. D&D commands more eyeballs. Eyeballs mean money. Maybe some nice person will build an audience doing a non-D&D game. And maybe it will last several months! Ha ha, you will think, that JDCorley, proved wrong again! But one day that person will wake up and think “This is nice . . . but money is nice too.” And there will be another D&D stream. Of course professional actors on professional sets will succeed over amateurs, and the eyeball logic of social media engagement will make that gap grow exponentially. We know this will happen because it’s happened in every other broadcast medium. And of course, of course, of course mediocrity will prevail, because people turn away from genius and talent, turn away from challenging material and towards the familiar and the reproduction of our worst selves. Tasteless mush and bigoted mania will inevitably dominate streaming whether anyone gets railroaded or not. Look to video games for our future. Like, really look and think about who gets paid when PewDiePie screams a racial slur, or doesn’t, and why. The money is going to pay streaming RPGs to be a certain way. What you think about them doesn’t matter. Only the money matters. Streaming RPGs will be the way Google and Twitch want them to be, not the way you or even the participants want them to be. Even if we resist for a little while, eventually, the money will win, as it always does. Hail Satan.

Corley’s critique of TRPG streaming echoes Jenkins’ concerns about the presence of top-down corporate convergence talk in popular culture. It also reflects the charges that have been laid against what is called the culture industry. “Culture today is infecting everything with sameness,” say Frankfurt School critical theorists Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno. “Film, radio, and magazines form a system. Each branch of culture is unanimous within itself and all are unanimous together.”

Conclusion

Applying McLuhan’s tetrad to make sense of the potential effects of the emergence of Actual Play video in the context of TRPGs as a predecessor medium produces an array of interesting contrasts. The TRPGs function of enhancing shared imagination shifts toward a legitimation of such activity in a broader social context, while the retrieval of pretend play ascribed to TRPGs transforms into a focus on performance, a much more self-aware and self-conscious practice. Interestingly, the obsolescence of the wargame in favor of the TRPG parallels the obsolescence of the game designer in favor of the GM; both represent a shift toward particularity: this particular character rather than bodies of troops, in the case of wargames; this particular gaming group rather than a more general gaming public, in the case of game designers. Conversely, the shift in problematic reversal—the medium taken to its extreme—moves in the opposite direction. The reversal of TRPGs into dysfunctional power fantasy represents a problem of individual imagination; the reversal of Actual Play programming into an object of consumption is part of the challenge of convergence culture.

Together, these models may be useful in navigating the contested discourses of TRPG design, play, and appreciation; they may also have some value in creating strategies for operating within a complex multimedia landscape.

–

Featured image is by 132369 from Pixabay

–

William J. White is an Associate Professor of Communication Arts & Sciences at Penn State Altoona, where he teaches courses in communication, rhetoric, and public speaking. An analog game studies scholar, he is currently working on a book about the Forge, an online discussion forum for tabletop RPG design, publication, and play. He is the designer of a self-published TRPG called Ganakagok (2009), and has written game supplements for Pelgrane Press and Evil Hat, Inc., including serving as the creative director on Evil Hat’s recently published Fate Space Toolkit.