Since its release in 2010, the post-apocalyptic tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG) Apocalypse World by Vincent Baker and Meguey Baker has inspired hundreds of games, hacks, homebrews, and playbooks under an umbrella now known as Powered by the Apocalypse (PbtA). TTRPG enthusiasts and players commonly refer to PbtA as a game engine, and for good reason: PbtA games use a common set of mechanics, rules, and design principles to tell stories in a vast array of genres and worlds, ranging from teen monster drama (Monsterhearts) to space sci-fi (Impulse Drive) to emotive cyberpunk (The Veil) (fig. 1). In this essay I take the idea that PbtA is a game engine seriously, arguing that it embodies feminist principles of platform design and provokes digital game engines to incorporate human input and computation in new and different ways. In doing so, I bring three fields into dialogue: game engine studies, feminist platform studies, and analog game studies. I suggest that framing PbtA as an engine builds a conceptual bridge by which these fields might meet in order to speculate in more concrete terms on alternative computational and relational structures for digital game engines.

Game Engine Studies

The emerging field of game engine studies examines the ways that digital game engines delimit what is possible and imaginable within games and virtual worlds. But game engine studies itself has done its fair share of delimiting. In The Persistence of Code in Game Engine Culture, for example, Eric Freedman defines a game engine as “a single piece of software that produces common functionality for multiple games; […] as a software abstraction of a graphics processing unit, engines are development tools for interactive digital content creation, and code frameworks that determine and control the attributes of the field of play across platforms and devices.” Built into the foundations of this field is the understanding that game engines are pieces of software enacted by a computer.

But the widespread use of the term “engine” in the TTRPG community seems to suggest that frameworks like Powered by the Apocalypse fulfill a similar role to digital engines like Unity and Unreal. Like digital game engines, they include logics that determine in real time what happens in response to player actions, and just as digital game engines include “a tool suite or content editor (for game creation and object-oriented asset manipulation),” the rules, logics, and objects of analog engines can be homebrewed, hacked, and retooled by players and developers. There is a critical difference, however: while digital game engines hide computational processes behind code that is typically made invisible to players, analog engines invite players to perform computational processes, by rolling dice and calculating the results, rotating or flipping cards, inscribing game world elements onto paper, or updating maps.

Platform Studies

The study of game engines is closely related to platform studies, a field that aims to decenter formal and visual analysis in the study of computational media by focusing on the affordances, limitations, and histories of hardware. In their seminal piece “Platform Studies: Frequently Questioned Answers,” Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost describe six misconceptions about platform studies, one of which is that “everything these days is a platform.” They argue for a focus on “the study of computational or computing systems that allow developers to work creatively on them,” noting rather sardonically that “we consider computational platforms without denying that there are other sorts of platforms as well—oil-drilling platforms, railroad platforms, political platforms, and communications platforms, to name a few.” For them, what makes platforms interesting as objects of study are the specific ways in which developers can interact with them through computation and code; as such, platforms must be programmable.

Feminist and queer theorists of platforms critique the hard boundaries delineated by Montfort and Bogost between formal analysis and the study of code, and between the human and the computational, with the goal of delineating a more complex relationship between body, computer, and media. Aubrey Anable, for example, notes that “in Montfort and Bogost’s model of platforms as the foundation of computational systems, […] the player’s body, identity, and audiovisual representations are peripheral to the primacy of the hardware” and calls for a feminist and queer analysis of platforms as “porous, penetrating, and penetrable.” For Anable and others, the hardware and software of platforms are inseparable from, and discursively created by, the contexts in which they are developed, used, and retooled.

Speculating on Queer Platforms

Feminist platform studies is founded upon the core belief in the potential for queer and feminist theories to reframe what is possible across digital and material worlds. According to this speculative line of thinking, the porousness of platforms creates space to imagine and encode new relational forms—but this possibility is often articulated in speculative terms, as if queer and feminist technologies do not yet exist.

For example, in “Queer OS,” Kara Keeling articulates queerness as a kind of operating system. Drawing on Tara McPherson, Keeling interprets the term “operating system” broadly as a set of logics that enforce particular behaviors and relations, including cultural, racial, and heteronormative logics as well as specifically computational ones. Keeling uses this definition in order to imagine an alternative set of queer logics—“a society-level operating system (and perhaps an operating system that can run on computer hardware) to facilitate and support imaginative, unexpected, and ethical relations between and among living beings and the environment, even when they have little, and perhaps nothing, in common.” While abstract, Keeling’s use of computational terms to describe the organization of social formations makes room to imagine actual computational processes, including engines and platforms, that encode more equitable relational structures.

The collaboratively-written piece “Queer OS: A User’s Manual” takes up Keeling’s challenge by suggesting several possible design principles for a queer operating system, many of which are articulated in opposition to common conventions in software design.

These include:

- Enthusiastic consent, as opposed to deliberately obtuse terms of service;

- Interfaces that “transform both the user and the system” in open and non-pre-determined ways;

- A more multiplicitous vision of a user-avatar, in opposition to discrete users identified by their data along demographic lines;

- Data structures that embrace uncertainty, contradictions, and crashes;

- Applications that are open source, alterable, and developed without single predetermined use-cases, in opposition to “killer apps” developed as technological “solutions” to complex social and political problems;

- Memory structures that complicate processes of remembering and forgetting; and

- Input-output features that allow for hardware and software that are traditionally excluded.

In developing these design principles, the authors adopt the language of a user manual while acknowledging that technical limitations currently make many of their ideas impossible—to the extent that they can only describe some of their ideas on the register of queer theory, without concrete ideas for how these principles might work on the level of design. While this approach is conceptually generative, suggesting ways for users to relate to technology that are more equitable, transparent, and historically situated, it positions queer technology as speculative and theoretical—something the authors make explicit when they draw from José Esteban Muñoz’s work on queer futurity, which imagines queerness as “not yet here.”

I argue that we do not need to look to the future to find queer technologies; queer game engines exist already. Feminist platform studies allows us to interpret terms like computation and operating system more broadly, and expanding them to include analog games reveals that tabletop role-playing games are already embodying many of the principles of Queer OS. In fact, analog game studies has already come to many of the same conclusions about users, bodies, and computation as feminist and queer theorists of technology.

Analog (Platform) Studies

Theorists studying analog games have long adapted frameworks from platform studies to understand the affordances and limitations of physical game objects and mechanics. For example, in “The Playing Card Platform,” Nathan Altice conducts a close reading of playing cards, arguing that they can be understood as a platform whose “‘hardware’ supports particular styles, systems, and subjects of play while stymying others.” In “What Counts: Configuring the Human in Platform Studies,” Ian Bellomy takes this line of thinking a step further, arguing that “while computation may be essential to platform studies, technology is not essential for computation” – humans can perform computation instead. Bellomy notes that analog games require players to perform computation and enact algorithms, and uses this framework to consider humans themselves as platforms with specific affordances. As both Altice and Bellomy realize, including analog games in these discussions problematizes the boundaries of platforms and of what constitutes computation and code.

However, while these interventions are provocative, Bellomy and Altice largely deploy them in response to the specific definition of platform studies put forward by Bogost and Montfort. Feminist scholars within platform studies, meanwhile, have made similar attempts to complicate the boundaries between people, platforms and code—attempts that have largely gone overlooked in the context of analog games, even as they resonate more with the questions analog games raise. By staging analog platform studies in conversation exclusively with traditional platform studies a la Montfort and Bogost, we risk missing out on accounts of platforms that, by attending to slippages and blurring between computational processes and embodied experience, can offer far more to the study of analog games. Reading Altice and Bellomy alongside “Queer OS: A User Manual,” for example, reveals that analog game mechanics, including playing cards and human computation, offer currently-possible adaptations of queer design principles.

I now turn to Powered by the Apocalypse, which I consider in detail as a concretization of queer design principles, as a sort of Queer OS. I focus on the discursive nature of PbtA’s development, the way it predicates play on collaborative improvisation, and its use of qualitative tagging to categorize in-game objects. These elements, I argue, mimic computational logic while leveraging the generative potential of collaborative co-creation, in ways that align with Queer OS’s principles for queer technology. I conclude each section by considering PbtA as a speculation on the queer possibilities of digital game engine, and suggest ways that digital game engines might adapt PbtA’s structures to create more equitable gamemaking processes.

What Does It Mean to be Powered by the Apocalypse?

Compared to relatively discrete digital game engines like Unity and Unreal, PbtA is a slippery object to analyze. The creators of Apocalypse World, nominally the inspiration for all PbtA games, express ambivalence about the idea that it is an engine at all: in an open letter on the Apocalypse World website, they say that PbtA “isn’t the name of a category of games, a set of games’ features, or the thrust of any games’ design. It’s the name of Meg’s and my policy concerning others’ use of our intellectual property and creative work.”

In this letter they provide an impossibly expansive definition of the engine, asking the reader, “is Apocalypse World an inspiration for your game? Enough so that you want to call your game PbtA? Did you follow Meg’s and my policy [with regard to] publishing it? Then cool, your game is Powered by the Apocalypse.” As such, there is no central database or ruleset that defines a PbtA game, only rules and design principles that are commonly recognized as PbtA by TTRPG designers and players. This messiness proves problematic for scholars (such as myself) who hope to conduct a formal analysis of PbtA, but it also creates space for developers to reproduce and reimagine the engine.

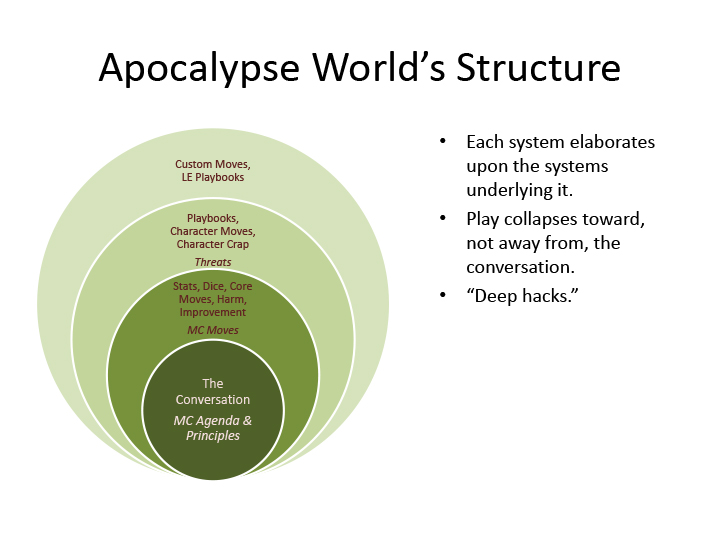

While the developers are reluctant to create an official definition for PbtA, they have shown interest in describing what they see as its common conventions. Vincent Baker has written a series of design guides and summaries on his blog intended for TTRPG designers, Game Masters (GMs), and players interested in developing their own PbtA games; each guide covers one mechanic he sees as conventional for the engine. In the first part of this series, Baker describes the structure of Apocalypse World as a layering of concentric circles (fig. 2). For Baker, “a crucial feature of Apocalypse World’s design is that these layers are designed to collapse gracefully inward,” and GMs and designers can remove or ignore layers of the design while maintaining a common experience. This productive tension between decentralization and design features, between “cool, your game is Powered by the Apocalypse” and collapsing “gracefully inward,” mean that the boundaries of the PbtA engine are decided by its users, namely developers, GMs, and players. Baker acknowledges this in an introductory article on his blog titled “What is PbtA?,” stating that “each new PbtA game changes and expands what “PbtA” means and includes,” and discouraging readers from policing the boundaries of the engine.

Of course, as feminist media scholars note, all platforms are discursively developed by their users. In their critique of strands of platform studies that separate technological constraints and affordances from social and historical contexts, Jussi Parikka and Thomas Apperley argue that “platforms are not recalled and rediscovered through platform studies, rather in the process of ‘doing’ platform studies, a uniform platform is produced.” Similarly, discussing Montfort and Bogost’s account of the Atari VCS (Video Computer System), Bellomy notes that “the console’s capabilities expand over time due to the growth of shared knowledge about tricks and techniques. In this way, the constraints of the platform cannot be cleanly separated from the community of practitioners.” But by making this notion explicit and building it into the very structure of its design, PbtA denies the teleology of normative applications, opening itself up to the possibility that its rules might be used for other purposes and in other directions than originally intended. This fulfills the queer design principle of applications, and suggests that leaving the purpose of an application up to its users could be generative and compelling.

This prompts us to ask: what might a digital engine so deliberately malleable and discursively oriented look like? How can digital game engines leverage the affordances created by the discursive formation of platforms? As tabletop developer Avery Alder points out in an interview with Bo Ruberg, one barrier to malleability in digital game engines is the requirement that developers have technical expertise. In tabletop games the technical barrier to entry is much lower: “there’s something beautiful about tabletop role-playing games where you can play a game once and then you know how to design your own. You engage with the mechanics of the game directly. The same isn’t true for digital games. You can’t just play video games until you understand the code. Tabletop role-playing games are transparent, replicable, and hackable.” But we might also see this as a provocation that digital games, and their engines, are not transparent, replicable, and hackable enough. By designing engines with the goal of accommodating disagreement, dissent, and alternative interpretation, we might create space for users to imagine their own unpredictable, queer relations.

Computation and Improvisation

I want to turn now to some rules and mechanics that are often part of PbtA games with, of course, the caveat that in so doing I might breed some dissent. With the explicit goal of inspiring more developers to create PbtA games, Avery Alder in 2013 wrote Simple World, a “streamlined, generic” PbtA game that does not involve any genre- or setting-specific elements. As a text both inspired by and inspiring of PbtA games, Simple World serves as a useful, though by no means comprehensive, object to read for common features and mechanics.

Perhaps the most recognizable mechanic in PbtA games, noted by both Alder and Vincent Baker, is the structure of moves. Moves in PbtA tend to utilize this basic structure:

- A player triggers a move by taking a relevant action.

- The player rolls two six-sided dice to decide the outcome of their move.

- On a ten or higher, the player succeeds;

- On a seven to nine, they achieve a partial or conditional success;

- On a six or lower, they fail, and the GM decides what happens next.

- The GM improvises the results of successes and failures.

This structure differs from other TTRPGs in several key ways. First, in other TTRPG systems, players often call on moves directly. For example, they might say “I use ‘Go Aggro’” to activate the Apocalypse World move of that name. In PbtA games, by contrast, Go Aggro triggers automatically when the player attempts to intimidate someone. Second, in contrast with other TTRPG systems in which players can either succeed or fail, PbtA games offer a third option when players roll a seven, eight or nine, in which “the [GM] will offer you a hard bargain or a cost. If you agree to that hard bargain or cost, you succeed at your goal.” This structure leverages the probability curve of two six-sided dice to encourage collaborative improvisation between players: by far the most common result is a partial success, in which the GM and player must compromise together on the course of events. Third, in contrast with other TTRPGs that emphasize pre-prepared scenarios by GMs, PbtA, as articulated by Alder in Simple World, cements collaborative improvisation as the core agenda of play, through the provocation to “play to find out what happens.”

The collaborative improvisation of PbtA structures a specific relational mode between players by combining computational processes with the affordances of the human platform. Bellomy addresses three affordances: the material and phenomenological experience of enacting computation; the assigning of meaning to objects to aid in performing computation; and the incorporation of non-algorithmic processes with computation. PbtA moves incorporate all three of these affordances in order to structure a specific relational mode between players.

Imagine a hypothetical play session. The player, stuck in a tough spot, devises a tricky, fancy maneuver to escape. The GM, who is tired of the player’s constant attempts at unconventional maneuvers, sees an opportunity to create hardship for their character if they fail: perhaps they will have to learn not to rely on such fancy techniques in the future (incorporating the non-algorithmic process of their own value system that prefers direct solutions over fancy ones). The player reaches for the two dice in the middle of the table (assigning meaning to them as computational aids), as everyone leans forward to see the result (cultivating a phenomenological experience of anticipation and anxiety in the process of rolling the dice)…and they roll a seven. The character succeeds in their trick, thwarting the GM’s goals. But the GM devises a complication: in completing their maneuver, the player reveals a weakness in their technique to their enemy, who will remember this in the future. They might not be so lucky next time.

This scenario leverages the affordances of the human platform to scaffold a specific form of compromise between the player and GM. What is unique here is not the use of these affordances—indeed, most analog games incorporate all of them in some way—but of the specific experience they create in combination with the mixed success roll in which both the player and GM get something, but not everything, they anxiously want. In tandem with PbtA’s insistence on improvisation over pre-preparation, these partial success rolls accumulate within a session and across a campaign, structuring the story that players tell together into an aggregate of small compromises, difficult decisions and complications. This aligns with the Queer OS User Manual’s notion of “an interface with the capacity for co-constitutive modification” in which it takes “self-modification as its ontological premise, such that interaction with an interface might transform both the user and the [system.]” PbtA’s move system is designed to “take self-modification as its ontological premise” by transforming the characters and the story beyond the original intentions of the players and the GM. This often creates friction—not only do players and GMs often have to compromise on their goals in frustrating ways, but mixed success rolls can spin out into new characters, subplots, and enemies in unexpected ways. (To return to our hypothetical play example, perhaps the enemy who noticed the player’s weakness will become a recurring character with their own motivations.) This friction aligns with the Manual’s insistence on creating data structures that center interference and instability, even if this creates “an unreliable system full of precarity, [which] reflects the condition of contemporary queer subjectivity.”

Different PbtA games leverage these complications towards different affective ends: the game Blades in the Dark, for example, uses mixed successes to create a building sense of complexity reminiscent of the heist genre, while Avery Alder’s Monsterhearts uses them to negotiate humanity, monstrosity and interpersonal power dynamics. Key to this mechanic in the PbtA engine, though, is the way it foregrounds tension and complexity. To borrow some vocabulary from McPherson, PbtA moves call attention to and engage with difference, but they also leave open the possibility for something more evocative and impactful to come from this engagement.

With current technology, we cannot create in a digital engine the kind of generative, collaborative improvisation afforded by the human platform as it is used in PbtA. But through its moves system, PbtA concretizes the challenge put forward by feminist media scholars by offering an example of what collaborative computational processes could look like. It prompts us to ask: how might we re-frame digital engines as a form of collaborative creation? How might digital engines integrate collaboration (with other users, with the content editor or interface, and with the logic of the engine itself) in ways that foreground difference, compromise, and the unexpected?

Tagging

One aspect of PbtA games is particularly evocative of computational processes: tagging, a form of categorization for objects and moves highly reminiscent of the same system in social media. In lieu of, or sometimes in addition to, complex stats and attributes, PbtA games use descriptive tags to denote what specific objects can do. Apocalypse World describes three types of tags: mechanical tags describe properties that connect directly to other mechanics (like how many bullets a gun can hold, or how many points of harm a knife can do); constraints denote restrictions on when an item can be used (like at what distances a ranged weapon can reliably work); cues inspire interpretations that create opportunities for improvisation in play (like “alive,” “loud,” “messy,” “volatile” or “valuable”). Players can create tags of their own, add or remove tags from objects through play, and negotiate the meaning and particular use case of the tags they create.

Apocalypse World, Simple World, Dungeon World, and numerous other influential PbtA games were released in the early 2010s, at the height of the popularity of the social media website Tumblr, and when the fanfiction repository Archive of Our Own (AO3) was gaining traction among fan communities. Both Tumblr and AO3 were known for their use of tagging, in which users could tag their content with keywords by which it would then become searchable. While tagging was likely developed to facilitate the categorization of vast amounts of user-generated data, the open structure of tagging allowed for social practices, norms and memes to form. As one study on Tumblr, Etsy and AO3 noted, “fans used tags in a variety of ways quite apart from classification purposes,” including “as meta-commentary and a means of dialogue between users, as well as expressors of emotion and affect towards posts.” The messy and chaotic ways in which AO3 users deployed tags resulted in the proliferation of volunteer “tag-wranglers” who attempt to refine tags to create consistency and searchability. Tagging in PbtA games allows for the same forms of categorization afforded by social media tags, and also creates the opportunity for similar emergent forms of interaction, improvisation, and user-created categorization as seen in Tumblr and AO3. Players might debate the meaning of the “alive” tag, apply it to an object out of curiosity as to what might happen, or use it to connote a feeling of hauntedness the characters sense from it (whether real or imagined). When combined with the partial success mechanic discussed previously, tags can also become complications that prompt further negotiation and compromise—the “alive” tag, for example, might become a form of possession that players must take into consideration when handling an object to which it has been applied.

Playing with specific tags in this way might inspire players to integrate them into future play sessions or to create new meanings for them. Meanwhile, tabletop developers can integrate their own systems of meaning and meaning-making into the tags they use in their PbtA games. For example, the cyberpunk PbtA game The Veil specifically encourages players to use tags to expand their understanding of the technology they use, to interrogate what is considered good and bad in their futuristic world. These interactions between play, interpretation and meaning-making evoke the Queer OS Operating Manual’s design principle of memory, in which, in engaging with tags, “users are haunted by the specter of their own memory, of their own utopian possibilities, of their own input, of the input of other users, and of their own processing habits.” Lived experience, history, and social context all influence the ways users deploy tags, creating both a sense of haunting and the possibility for new and narratively compelling interpretations. Tagging is thus one example of the ways that computational processes can inform analog tabletop engines, while provoking new possibilities for these processes in digital engines.

PbtA’s use of this computational process towards generative ends challenges us to ask: what other tools already exist in digital engines that might allow users to create new systems of meaning-making? How might digital engines leverage the unexpected hacks, workarounds and systems of meaning that players develop within them?

Conclusion

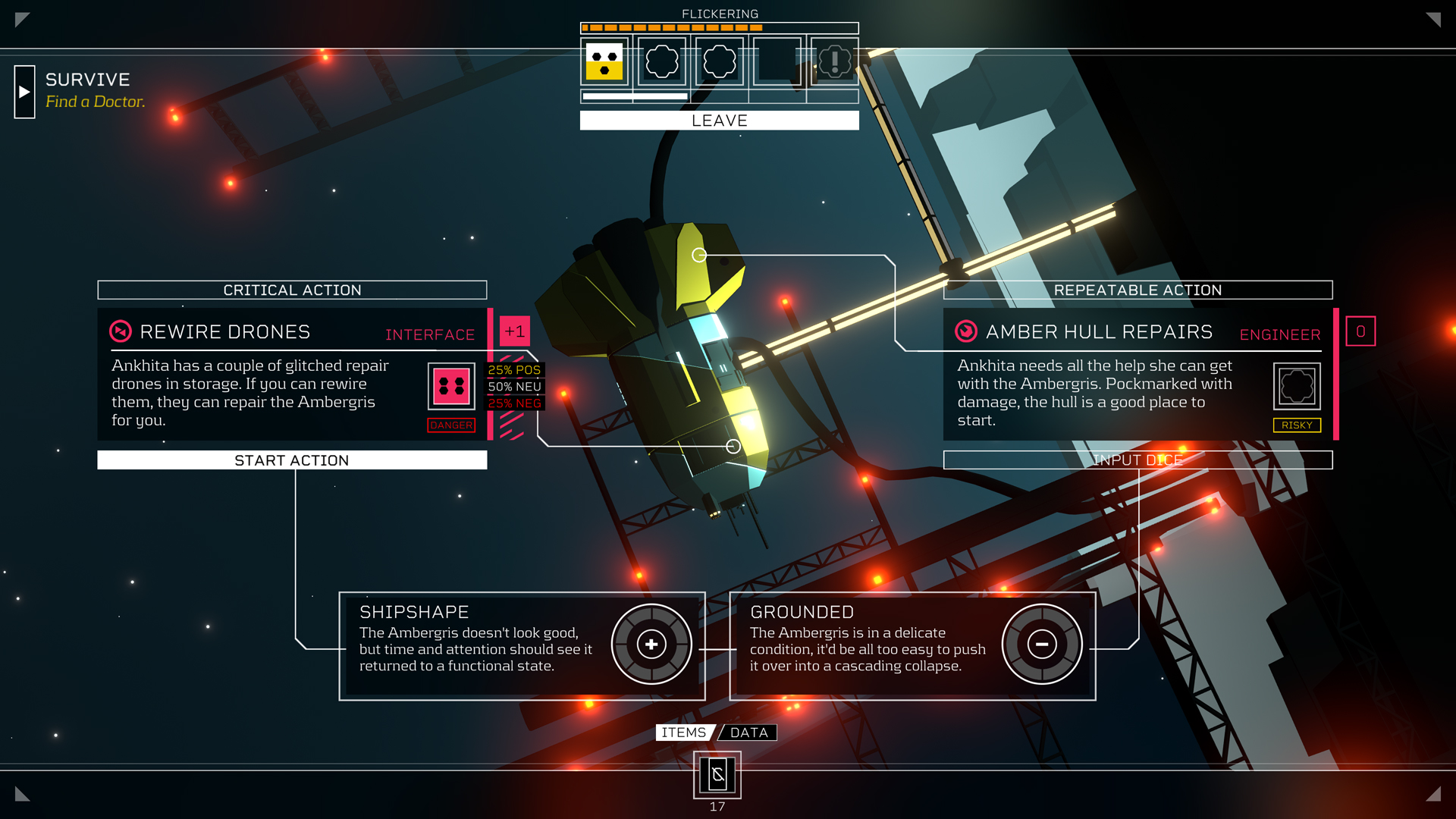

The notion that tabletop RPGs speculate on what is possible for digital games is nothing new: TTRPGs have long inspired digital games and game systems. Many digital games, including Baldur’s Gate, Diablo, Disco Elysium, and Citizen Sleeper were all inspired by TTRPG systems, and innumerable game worlds have been inspired by tabletop RPG campaigns conducted by their developers (fig. 3). Citizen Sleeper in particular provides a compelling example here, as its mechanics are reminiscient of PbtA specifically. Citizen Sleeper, a single-player narrative game, is played across a number of in-game days; each day, the player rolls a set of dice and then allocates the resulting numbers to specific actions. The number on the roll determines the likelihood of succeeding at a given action; some rolls can result in a “neutral” outcome, reminiscent of the partial success mechanic from PbtA (fig. 3). As Citizen Sleeper exemplifies, the forms of computation suggested by tabletop RPGs inspire digital game mechanics, even as digital games are not yet capable of generative, improvisational storytelling in the same ways as analog games. Taking seriously the notion that systems like PbtA are game engines allows us to better articulate this relationship.

Previously I described a tendency by feminist platform studies to situate its interventions in the future, as technological and social structures that do not yet exist. As I have argued here, concrete forms of these provocations already exist in the form of analog games. Expanding the definition of game engines to include the analog allows us to see the ways in which creators are already producing queer entanglements between body, computation, and system. For the study and development of digital game engines, it also illuminates a path by which they might adopt queer design principles, in order to facilitate gamemaking processes that are “curiously porous, queerly promiscuous, and radically leaky” and thus push the boundaries of the medium. For scholars of analog games, incorporating feminist theories of platforms gives us a rich new vocabulary with which to consider questions of human computation, analog platforms, and embodied play. It also prompts us to reimagine the way we relate to digital studies. As PbtA reveals, analog games can offer to the digital a concretization of what is not yet possible, a kind of queer possibility that is generative for new technologies and new forms of design.

–

Featured image from Pixabay: https://pixabay.com/illustrations/angel-of-death-art-gothic-colors-1875423/.

–

Abstract: In this essay I argue that analog game engines speculate on what is possible for the digital, in a way that concretizes queer visions of the messy relationship between humans, systems, and computation. Drawing on Kara Keeling and Tara McPherson, I analyze the analog game engine Powered by the Apocalypse as an example of Keeling’s notion of a “Queer OS,” or an operating system that encodes queer relational structures. In my close analysis of Powered by the Apocalypse’s mechanics and conceptual boundaries, I bring feminist platform studies and analog game studies into dialogue in order to argue for a more expansive definition of “game engine” that accounts for the ways in which analog games imagine forms of computation and human-computer interaction that are not yet possible for digital game engines.

Keywords: TTRPG, PbtA, game engines, queer, operating system, platform studies, analog games, digital games

–

Kaelan Doyle-Myerscough (they/he) is a PhD student in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. Kaelan’s dissertation research centers on the theory, politics and practice of worldbuilding. As part of their critical work, Kaelan develops games that put into practice radical and experimental worldbuilding methods; their games have been showcased in Toronto, Hong Kong and Japan. Kaelan’s scholarly work has been published in InVisible Culture and the Dark Arts Journal, and they have served on the Board of Directors for the Queerness and Games Conference (QGCon) since 2019.