Monstrosity has been an important focal point of analysis for scholars interested in how certain bodies and behaviours have been policed, punished, or even rejected from dominant social groups throughout history. The figure of the monster symbolically polices the borders of what is permissible, and as J. J. Cohen has argued, to step outside of social norms risks either “attack by some monstrous border patrol or (worse) to become monstrous oneself.” The monstrous has therefore been deconstructed as a broad category of alterity, marginality, deviance, and transgression. As many scholars of mythology, fairy tales, literature, and popular culture have argued, the act of killing monstrous creatures can be understood as a violent and cathartic re-establishment of the normative, dominant, and patriarchal order—a way to expel or erase the unwanted “Other.”

Unlike mythology, literature, or other media, most games invite the player directly into the story by having them adopt the role of a character and engage in gameplay. In the case of Dungeons & Dragons (hereafter D&D), this means role-playing interactions and enacting the gameplay, including the imaginative slaying of monsters, thereby potentially making players feel as though they are participants complicit in the game’s events. D&D, like many role-playing games, is heavily influenced by the fantasy genre, as well as myths, legends, and fairy tales, and so provides a power fantasy by positioning players as the heroic representatives of normative, patriarchal society tasked with slaying villains and monsters in order to save the day. Ludic monsters or monstrous races in fantasy role-playing games are often designed or described with certain signifiers that code them in relation to identifiable real-world groups. In critical and scholarly writing on D&D, this coding has been primarily unpacked in terms of race, which has resulted in recognition and acknowledgement by Wizards of the Coast that racism has been built into every aspect of the game, from lore to artwork to character/creature statistics. Less work has been done unpacking this coding in terms of connecting monstrosity to other identity signifiers such as gender, though there are several female monsters in D&D’s Monster Manual. As Aaron Trammell and I have discussed, the design of these monstrous women often adheres to common popular culture tropes that reinforce harmful misogynistic beliefs and uphold the primacy of hegemonic patriarchal ideology. In other words, women are presented as the sexual Other through well-known monstrous archetypes, especially the witch, vampire, siren, and succubus—misogynistic constructs used to warn, control, and punish transgressive women. Given that many fantasy games are heavily influenced by mythology and popular culture—repositories of ideological meaning and messages—and that most games are designed by teams composed entirely or mostly of men, it is perhaps no surprise that much of the misogyny inherent in the design of female monsters in mythology and popular culture manifests in games as well.

In order to contribute to scholarship focused on female monstrosity in D&D, this article is a close reading of three female monsters featured in the Fiend Folio: the kelpie, a deceptive, grotesque siren-like figure drawn from Celtic mythology that lures unwary men to their deaths in the water; the penanggalan, a female vampire drawn from Southeast Asian mythology that appears as an attractive woman during the day only to secretly detach her head from her body at night and drink players’ blood while they sleep; and Lolth, the demon queen of spiders who can change her form from giant spider to beautiful female dark elf and is worshipped as a goddess by the drow. While most monsters in the Fiend Folio are male-coded or gender neutral, these three monsters are overtly female-coded, and, like female monsters in the Monster Manual, they are designed and described using well-established tropes of female monstrosity from mythology, folklore, and popular culture. This article therefore builds upon my previous work to demonstrate how these monsters fit into a long patriarchal tradition of positioning powerful women as deceptive, manipulative, and predatory femmes fatales while also dehumanizing them as evil monstrous creatures or demons deserving only of consternation and death.

The kelpie: Alluring underwater women or… horses?

The kelpie is a shapeshifting water spirit from Celtic mythology, whose default form is a beautiful black horse that inhabits deep water, luring unwary swimmers, especially children, into the depths where it devours them. Although kelpies can shapeshift into human form, most known stories have them turning into human men. However, in artistic representations of kelpies, such as Thomas Millie Dow’s and Herbert James Draper’s paintings, both titled The Kelpie, they are instead portrayed as naked young women (figs. 1 & 2). Taking a horse creature and “reinterpreting” it as a beautiful woman resembling a water nymph or siren was likely a purposeful choice, according to Nicola Bown, which changed the nature of the creature’s threat: “The ‘real’ Kelpie was a perilous creature, but although Draper’s Kelpie seems to have been divested of his terrors, she has her own dangers.” Although Bown does not read this reinterpretation through a gendered lens, turning a male horse into a conventionally attractive naked young woman is a way of sexualizing the creature and making it appealing (and therefore dangerous) to a heterosexual male viewer.

In the Fiend Folio, the kelpie’s creator Lawrence Schick draws on both the woman and horse aspects of the kelpie while reducing it to little more than “a form of intelligent aquatic plant life.” In their natural form, kelpies “resemble a pile of wet seaweed” but they are able to assume any form they choose. Contrary to the myth, in which a horse monster occasionally takes human form, Schick’s version of the kelpie typically assumes the aspect of “a beautiful human woman in order to lure men into deep waters” but also occasionally takes the form of a horse. Unlike Dow’s or Draper’s vision of the kelpie as a beautiful young woman, Schick’s kelpie cannot hide her true nature, as her body (what he calls “the substance”) still looks like seaweed regardless of the shape she takes, rendering her appearance “somewhat grotesque” (fig. 3).

To hide her true form, the kelpie casts charm in order to convince her victim that he is indeed seeing “the most wonderful, perfect and desirable woman (or steed, perhaps).” The victim will then leap into the water to obtain either the woman or the horse (both positioned as equally alluring objects of desire), willingly drowning himself to be with her/it. Interestingly, although the description insists that a charmed victim willingly drowns himself, the image accompanying the entry shows the kelpie with its seaweed tentacles wrapped around her victim’s body, and he appears to be struggling against her with a disgusted and horrified look on his face, thereby contradicting the text. The image also shows a female warrior with a smirk on her face, swimming towards her male companion with a knife in her hand, presumably to rescue him. This is because “females are immune to the spell of the kelpie,” and while this statement could be read as queer erasure—assuming that a woman would not be attracted to another woman—it is explained with speculation that women are exempt from the kelpie’s power either because the creature exists as punishment for men’s transgressions or because they were created by an evil female deity who made females immune to its power “in proper regard for her own gender.”

Like many of the monsters in the Fiend Folio, the kelpie is derivative with aspects drawn from both the kelpie of Celtic mythology and the siren of Greek mythology. Sirens were traditionally half-bird women but over time they were reimagined as half-fish women, with fish tails in place of lower legs. Either way, the mythological siren (an all-female species) lures (male) sailors to their deaths by shipwreck or drowning, usually through an entrancing song or seductive behaviour. In this sense, the siren can be understood as an iteration of an older archetype of female monstrosity: the succubus. The mythological succubus is a demonic woman who seduces and destroys men through life-draining sexual activity and also kidnaps, harms, or murders pregnant women and infants. The name of this monster is derived from the Latin succubare (“to lie under”) and she is often depicted as a beautiful young woman with animal aspects, like claws, a serpentine tail, or bat-like wings. This female monster archetype is ancient: “a universal image that appears throughout world history in mainstream and marginal cultures, acquiring a multiplicity of faces and coming to be known under many names.” Indeed, the succubus has taken many forms in mythology, folklore, and popular culture from around the world. Like the female vampire, the femme fatale, the black widow, or any other female archetype that uses her beauty, charm, or sexual appeal to deceive, manipulate, seduce, and ultimately destroy male victims, the succubus is an embodiment of misogyny, a symbolic figure that sends the message that women—especially conventionally attractive and sexually active women—are fundamentally dangerous to men. The succubus and her various iterations are what Mary Ayers has called “one of the most crudely dehumanizing images of woman.”

The kelpie’s description in the Fiend Folio is similarly dehumanizing, framing the female body as nothing but a lure for heterosexual men, desirable as a possession in the same way a horse would be. In addition, the description of the kelpie’s true form as “grotesque” underscores her deceptive nature and also makes her into a kind of “bait-and-switch” trap. This is a common design trope for female monstrosity—in which the female monster hides her true monstrous form under a beautiful disguise (using the spell “charm” in the case of the kelpie) or appears beautiful at first to lure her male victims before revealing her true form. That kelpies use their own bodies as decoys or lures is important, because as Mary Ann Doane has argued, the masquerade in which a woman plays up her sexuality to manipulate men, “is aligned with the femme fatale” and “regarded by men as evil incarnate” because it represents a power that women can potentially use against them.

This idea is emphasized in the description of the kelpie as a creature that was created by the sea god as punishment for men, which again draws on ancient patriarchal mythology. For example, the first woman in Greek mythology, Pandora, was created explicitly by a male god to vex mankind and unleashed miseries on the world. Similarly, Eve in the Abrahamic creation myth is blamed for committing the first sin and condemning humans to an existence full of suffering. It is no coincidence that these extremely patriarchal cultures developed myths that position woman as man’s punishment or the cause of his punishment. Indeed, female characters/monsters who fall into the succubus/siren/femme fatale archetype exist as means to disempower women, justify their oppression, and legitimize male control of society. They are also manifestations of the same misogyny that causes victim blaming and “slut-shaming”—the idea that women’s bodies are inherently enticing to heterosexual men.

The penanggalan: A female vampire and… disembodied floating head?

Although the Fiend Folio’s penanggalan was designed by Stephen Hellman, like the kelpie it is a culturally appropriated monster.The bestiary’s entry makes no mention of its origins, but the penanggalan is a mythical Southeast Asian creature—one of several Malay ghost myths. She is “a female vampire-type undead of fearsome power and nauseating appearance” and a “vile creature [that] appears during the day as an attractive human female.” Like the kelpie, the penanggalan’s true form is “nauseating” and “vile”—a floating head with internal organs dangling from her neck—but she disguises herself as a normative human woman in order to lure her victims into a false sense of security so at night she can drink their blood while they sleep (fig. 4). As with many vampires in mythology and popular culture, the penanggalan hypnotises her victims before draining them, and they have no memory of the attack in the morning. This creature is so horrifying that any witness to the penanggalan’s head detachment must make a saving throw or die immediately, and even if he (the entry almost exclusively uses masculine pronouns when referring to the penanggalan’s victims) succeeds at the saving throw, he must behave as though the spell “feeblemind” has been cast upon him, meaning his intellect and personality have been shattered and his intelligence and charisma scores are reduced to 1.

If the penanggalan kills a male victim, he remains dead, but if she kills a female victim, she rises from the grave after three days to become a penanggalan herself. Unlike the kelpie, which is actually just intelligent plant life that disguises itself as a woman, the penanggalan is therefore unambiguously female. The entry notes that the penanggalan prefers the blood of “young children or pregnant females” and in general prefers female victims, perhaps because of the chance to create more of her kind. However, throughout the entry her victims are presumed male, and the fact that she preys on pregnant women and children while simultaneously being a threat to men while they sleep reinforces her association with the succubus. Although she does not drain them through intercourse, the vampire’s act of draining blood by penetrating the victim has long been considered a metaphor for sexual activity, and the succubus and vampire are related archetypes—creatures that drain their victims, killing them while they sleep at night.

Like the kelpie, the penanggalan paints a particularly misogynistic picture—women might actually be deceptive monsters who hide their true forms behind pretty faces in order to lure men to their deaths. They also pose a threat to other women and might “contaminate” them by turning them into the same kind of transgressive monstrosities. Although there are several monsters with neutral alignment throughout the Fiend Folio, the female monsters are always evil. This helps justify the desire to kill them in what I see as a re-enactment of the heteropatriarchal violence directed at sexually liberated and transgressive women. In this way, these games symbolically represent the victory of patriarchal control over female sexuality, thereby alleviating the sexual anxieties these monsters embody. This is not limited to female monsters but is applied to any transgressive woman or femme fatale who is eradicated to re-assert masculine power, as discussed by Doane: “the femme fatale is situated as evil and is frequently punished or killed. Her textual eradication involves a desperate reassertion of control on the part of the threatened male subject.”

Lolth: Demon queen, goddess, and… giant spider?

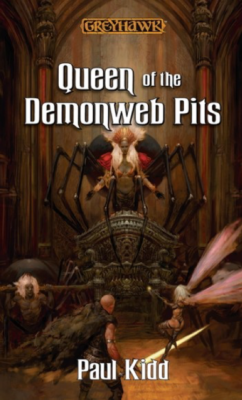

Lolth is arguably the most iconic female monster in D&D: a hybrid spider woman and a goddess figure, Lolth was designed by D&D creator Gary Gygax and introduced in 1978 as the game’s first “demon lord.” She is the main antagonist of the 1980 module Queen of the Demonweb Pits, which was voted the single greatest adventure of all time by Dungeon magazine in 2004. The best part of that adventure, according to the magazine, is Lolth herself: as fantasy and science fiction author Jean Rabe stated, “the Queen is one of the best D&D villainesses ever. Beautiful, crafty, and insidious.” In addition, in the final issue of Dragon magazine, Lolth was declared one of the greatest villains in D&D history. Countless pieces of fan art have been created featuring Lolth, and while much of it is sexualized, the sheer number indicates her popularity among fans.

Lolth is a chaotic evil goddess and the chief deity of the drow elves, a race of evil, dark-skinned, white-haired humanoids who live underground. Although she is a monstrous creature, because she is also a deity the only monster bestiary she appears in with her own distinct entry is the Fiend Folio. According to the surprisingly brief entry, Lolth usually appears as a giant black widow spider who “also enjoys appearing as an exquisitely beautiful female dark elf,” though the accompanying artwork shows her in a hybrid form as a spider with a woman’s head (fig. 5). The description of the demoness mostly focuses on her statistics, abilities, and strategies for how to defeat her rather than providing a detailed description of her role in drow society or her desires as a goddess. In this sense, she is reduced to nothing but a monster to slay in the Fiend Folio, whereas in other texts her backstory, motives, and role are more fully explored.

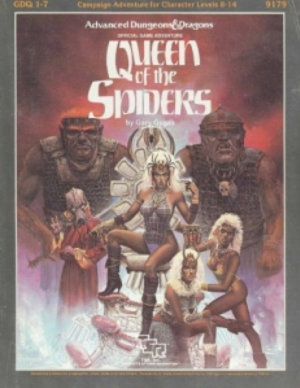

Lolth is portrayed in official material other than the Fiend Folio as having brown, grey, or purple skin, and she generally takes the form of a giant spider, a hybrid spider woman with a humanoid top half (a “drider”), an entirely humanoid drow woman, or something in-between these forms (fig. 6). In her drow form she is sexualized and racialized; for example, on the cover of Queen of the Spiders, she is dressed like a dominatrix with skin-tight clothing, exposed legs, and high-heeled boots, thereby adhering to the trope of exoticized and fetishized femme fatale (fig. 7). Although she is a powerful queen/demoness/goddess, her visual design underscores the point that she was designed with a heterosexual male audience in mind. Along with her sexualization, Lolth is unambiguously evil, thereby sending the message that powerful women are dangerous and again adhering to the trope in Western fantasy that reinforces an association between dark skin and evilness. For example, in the 4th edition of the Monster Manual Lolth is described as “both cruel and capricious; she demands many sacrifices and demonstrations of loyalty. She also foments internal discord to keep her chosen people tough and ruthless.” Her clerics are all female, and they also rule drow society, making it a matriarchal society. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this is framed as a bad thing, with the drow performing human sacrifices to please her and living in a constant state of competition and conflict because Lolth loves chaos and violence. Gygax reveals his own misogynistic approach to game design by clearly associating female power with evilness, cruelness, and capriciousness.

Lolth’s detailed backstory reveals that the reason she became a spider monster and the evil, cruel goddess of the drow is so she can torture them because they were the creations of her hated ex-husband. Her motivation is therefore vengeance against a man, which undermines her positioning as a potentially empowering goddess figure. On the other hand, her image as a powerful goddess—albeit evil—is what remains in the popular imagination and also what makes her such a popular villain. Even the prayer that her followers say to her reinforces this strangely satisfying matriarchal twist on the violent empowerment she represents:

Great Goddess, Mother of the Dark, grant me the blood of my enemies for drink and their living hearts for meat. Grant me the screams of their young for song, grant me the helplessness of their males for my satisfaction, grant me the wealth of their houses for my bed. By this unworthy sacrifice I honor you, Queen of Spiders, and beseech of you the strength to destroy my foes.

Unfortunately, Lolth’s empowerment is premised upon the patriarchal assumption that powerful women (especially women of colour) must be evil and cruel—the goddess recast “as devil, monster, and whore.” She also reflects Caputi’s critique of female villains in popular culture and the way their defeat at the hands of male heroes reinforces patriarchal ideology and male supremacy by demonstrating and celebrating the taming or destruction of transgressive women: “the primordial serpent goddess of the underworld becomes the Devil … the potent Bitch Goddess becomes the high-heeled and tightly bound dominatrix … The Death Goddess is hated as a castrating and ravenous monster … the femme fatale, rotten underneath her façade of beauty.”

Lolth is interesting from a feminist perspective as a powerful goddess figure ruling over a matriarchal society, but she was designed by a man as a “chaotic evil” villain and presented as a powerful fiend for high level (and likely male) players to confront and murder. She is therefore a misogynistic construct that is designed to reinforce hegemonic ideology and uphold the primacy of the “heroes.” The Fiend Folio underscores this by positioning her in a bestiary alongside monsters and beasts, and focusing primarily on her statistics, abilities, and strategies to defeat her. While she has been celebrated by many fans who envision her in creative and interesting ways, D&D itself does not leave space for her to be redeemed, reclaimed, or identified with. Fans must do that on their own.

Conclusion: The problems with female monstrosity

The tropes of the evil, seductive, deceptive, monstrous woman who lures men to their death like the kelpie, disguises herself as a human woman before revealing her true form like the penanggalan, or is an evil racialized and sexualized queen/goddess like Lolth draw on well-known and ubiquitous imagery in popular culture and mythology. This imagery is misogynistic in that it sends the message that women—especially powerful women and/or those who are sexually liberated or transgressive—are deceptive, seductive, and dangerous and that their bodies exist as traps, lures, or objects to be consumed by the male gaze. These women signify a threat to patriarchal society and so are made monstrous and therefore dehumanized and categorized as evil. An extremely effective way of dehumanizing someone is to make their body hybrid, transformative, or grotesque like the kelpie’s seaweed form, the penanggalan ‘s dangling organs and floating head, or Lolth’s spider body (the spider is of course one of the most hated and feared creatures). Popular culture is a powerful weapon in the patriarchal arsenal and an extremely effective way of reinforcing the cultural positioning of transgressive women as evil or monstrous. The representation of women in media is embedded in the historical context of power, knowledge, and hegemonic ideology, which in the case of the Fiend Folio is related to the real and presumed audience of D&D creators, writers, artists, players, and fans in the 1970s and 1980s. There are only three overtly female monsters in the Fiend Folio, and given the dominance of the straight, white, male creative vision behind its production, it is no coincidence that all three adhere to this deeply harmful femme fatale archetype.

In games, players (who generally consider themselves “heroes”) are forced or encouraged to confront, fight, and murder these creatures/characters for a reward, thereby sending the message that “men are good, women an evil to be overcome.” As Emma Vossen has argued, these monstrous femmes fatales also send the message to women players that “this game is not for you, games are not for you,” thereby adding to the exclusion that many women players already feel. This is not just because these monsters are female—after all, in the Fiend Folio there are far more male or gender-neutral monsters—and so I am not arguing that there should be no female monsters in games. Rather, I am advocating for female monsters that are not monstrous in relation to their sexuality, are not deceptive and seductive traps or lures for presumed male players, do not draw on mythological creatures that serve patriarchal ideology like the siren or succubus, and do not adhere to the femme fatale archetype. There are almost never seductive male monsters in Western games, popular culture, or mythology; rather, male (or gender-neutral) monsters are designed with more creativity and variety—unlike female monsters, their horror is not always sexual. In other words, the harmful tropes of female monstrosity these entries in the Fiend Folio uncritically remediate are an unnecessary convention. Instead of designing female monsters that simply embody misogynistic patriarchal tropes, game designers could instead re-envision female monstrosity and make space for more creative and unique approaches to the monstrous. Perhaps there is need for a new crowd-sourced bestiary for D&D, one that reflects the diversity and socially progressive values of the game’s contemporary player base.

–

Featured image from The Met Open Access: George Fuller, And She Was a Witch, 1877-84. Public Domain.

–

Sarah Stang, Ph.D., recently received her PhD from the Communication & Culture program at York University in Toronto, Canada. She is the editor-in-chief of the game studies journal Press Start and the former essays editor for the academic middle-state publication First Person Scholar. Her published work has focused primarily on gender representation in digital games and has been featured in journals such as Games & Culture, Game Studies, Human Technology, and Loading. Her current research explores the intersection of gender, hybridity, and monstrosity in science fiction and fantasy games and other media.