Despite some successes in the contemporary gaming community at creating spaces for diverse players and perspectives, examining the early roots of the tabletop role-playing (TTRPG) game community as a subculture that was dominated by white men provides vital insights into why the community still struggles with issue of race and gender. Placing the origins of these games into the context of the Long Sixties and their aftermath, the early formation of a TTRPG “style” emerged as a site in which players engaged in a form of escapism that provided more control in fictional worlds than the perceived chaos of reality in the late 1970s. Though these fictional worlds may have fulfilled escapist desires, the collaborative nature of TTRPGs solidified an emergent “imagined community” of players who also negotiated significant “real-world” issues within the development of a subcultural style of TTRPGs. Examining early example of race and gender in TTRPGs highlights the inherent biases and some initial attempts to engage with those biases. Using fanzines, personal reflections of my own experience as an African-American gamer since the 1970s, and the game manuals and the ten years of Dragon Magazine as primary sources, this article will argue that there was a distinct subcultural style of TTRPGs that reflected and reinforced white male-dominated boundaries. Furthermore, the collaborative nature of the games allowed for the transfer of biases, while also eventually contributing to a negotiation of homogenic boundaries, permitting some positive changes within the contemporary community, even as some players cling to the ideologies of marginalization present in the foundations of early TTRPGS. The first ten to eleven years of TTRPGS from their inception with Dungeons and Dragons in 1974 offered insights into the influence of the social unrest of the Long Sixties on the development of TTRPG spaces and consequently the influence these early games had on the TTRPGs that followed.

Leveling Up: A New Historical TTRPG Methodology

Scholars debate the status of RPG status as a subculture. As Dick Hebdige notes, “the meaning of subculture is, then always in dispute” and that “culture is a notoriously ambiguous concept.” Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning of Style provides a framework for studying how fans built and continue to shape a style for TTRPG culture. Hebdige’s work looked at the style of various aspects of youth Punk subcultures in the UK during the 1970s, using a Marxist and structuralist view to engage with the socioeconomic, racial, and class environment of these groups. Hebdige also argues that his subjects were “cultures of conspicuous consumption… and it is through the distinctive rituals of consumption, through style, that subculture at once reveals its ‘secret’ identity and communicates its forbidden meanings.” Additionally, Hebdige used the term bricolage to describe how subculture took disparate elements and appropriated them to from a style as with the “teddy boy’s theft and transformation of the Edwardian style” or “Union jacks [that] were emblazoned on the back of grubby parka anoraks.” However, Hebdige’s base idea of subcultural style, differs when applied to TTRPG players because their style does not represent their ideas, rather their ideas and creations became their style. Unlike other subcultural groups, TTRPG fans did not always don specific clothing or accouterments; instead, they projected their style through their fictional creations. Pictures of the young men who played these games often show them wearing collared shirts, sweaters, and sometimes ties. Nothing about their outward appearance distinguished them from other middle-class American youths. Therefore, the TTRPG style did not stem from a shared distinctive appearance that differentiated them from mainstream culture in the sense that the Punk movement had a “look” that appropriated Edwardian style or other elements that set them apart. Additionally, Hebdige’s usage of the idea of bricolage, French for something created from a diverse range of things, also fits the spectrum of disparate elements and ideas that contributed to the TTRPG style. When using bricolage in relation to the TTRPGstyle I am referring to the things TTRPG fans created for their games and worlds, including but not limited to, monster’s, NPCs, magic items, fictional towns, encounters or modifications, of existing official published game materials. In some cases, these bits of bricolage went on to become official published material for games like D&D or completely new TTRPGs. Therefore, the imagined worlds that TTRPGs are played in reflect the TTRPG style.

RPG enthusiasts’ formation of a style also aligns with other cultural theories. Often applied to film and television studies, reception theory engages with how audiences receive and interpret media content. In “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Disclosure,” Stuart Hall describes the way content creators encode content while audiences decode what they consume. Hall’s work examines the semiotic codes contained in media and how cultures interpret those codes based, in part, on an application of Antonio Gramsci’s work on ‘hegemonic’ and ‘corporate’ ideological formations. With film, television, or books, the encoding/ decoding dynamic generally happens in one direction. A writer creates the content while fans receive and interpret that content. However, in the case of things like fan fiction and TTRPGs, the decoders reencode the material, becoming a gestalt of encoder and decoder. Unlike fan faction authors, TTRPG players generally perform this reencoding as a group. For the TTRPG community this sharing of ideas paralleled what Eric Zolov called a “shared repertoire,” which youth used in the Long Sixties to link themselves “to each other struggles.” Here again, TTRPG fans did not share “fashion statements, and music” but they did share “imagery” through the fictional places and personas they made. Nor were TTRPG fans sharing a political struggle per se, but they creating worlds that shared certain Eurocentric and Orientalist paradigms, these worlds were their shared repertoire and their bricolage. Therefore, the non-physical and fictional nature of their creative exchanges built a “style” that parallels but does not mimic the styles of other subcultures. Taken together Hebdige’s ideas of style, Hall’s roles of encoder and decoder, Zolov’s shared repertoire, the actions of TRPG fans in shaping their own worlds, monsters, and other materials from published materials highlights the shared threads of these theorists. These seemingly unrelated concepts intersect to create the TTRPG style. Fans shaped an enduring legacy of shared creation that manifested in a myriad of positive forms, though their biases coupled with the need for escapist entertainment to cause some unfortunate early trends. However, in both cases, reencoded material may go through a series of revisions as multiple fans or groups reinterpret the content. The elements of the TTRPGs style combined to create worlds, monsters, and other materials that reflected the homogenic make up of predominantly white, male, middle-class fans in the alert years of the hobby. Most example of place not based on Europe were filled with problematic stereotypes that Othered and exoticized non-Eurocentric lands, peoples, and cultures. Fans developed an enduring legacy of shared creation that manifested in a myriad of ways, though the biases of cultural hegemonic early fans established some unfortunate and long-lasting trends within the nascent TTRPG community.

On the surface, the confluence of race and gender might seem unrelated when applied to the style of the RPGs that arose in the aftermath of the Long Sixties. However, these seemingly unrelated components coalesced to contribute to the look and feel of early TTRPGs. These game realities offered a measure of control that the real world could not provide, and the ingrained cultural biases of the predominant TTRPG players in the 1970s and 1980s made race and gender relevant in sometimes subtle but significant ways. Scholars continue to debate the role of subculture as a concept when applied to the TTRPG community. Sociologist Gary Alan Fine identified the community as a distinct sub-culture. Additionally, TTRPG scholar Jennifer Grouling Cover notes that a “second wave of fandom scholars has been more careful about falling into binary thinking and has sought to explicate fandom’s role within the dominant, capitalist system.” Other scholars argue that “RPGs are not a niche subculture for a specific group of people– instead, they have a broad reach throughout geek and leisure cultures.” To reframe subcultural critiques, Esther MacCallum-Stewart and Aaron Trammell point out that Mia Consalvo proposes that the term ‘Gaming Capital’ “contextualize[s] what RPG groups are doing and avoids some of the assumptions about ‘subcultures’ having a physical aspect because gaming fans may never come together fully.” These distinctions and efforts to avoid relegating subcultures to reductive frameworks illustrate the complexities of defining the TTRPG style.

The limited academic study of the first TTRPGs in the context of the massive social change of the 1960s and 70s complicates historical examinations of this subject. However, a few scholars have engaged with these games in a modern milieu, offering some critical suggestions for further studies of TTRPGs. Jennifer Grouling Cover’s, The Creation of Narrative in Tabletop Role-Playing Games explores the cooperative construction of narratives in RPGs. Cover uses her experiences playing TTRPG’s to describe how players shape narratives in TTRPGs. She also posits that “with so little scholarship currently available on the tabletop role-playing games (TTRPG), we must first ask how we should define and study it.” Cover also argues “that TTRPGs cannot be subsumed under the study of other games, particularly computer games, nor should they occupy a position of prior and inferior text.” As she denotes, the relatively few academic studies of RPGs tend to assess their many variations, TTRPGs, Live-Action Role-Playing Games (larps), and particularly Computer Role-Playing Games (CRPGs) as a single entity. In fact, many of the critiques about whether to classify RPG enthusiasts as a subculture, such as their “broad reach” or their lack of coming “together fully,” address the entire RPG community and not its distinctive groups like TTRPG players. Though all RPGs share the same roots and similar themes, Cover suggests “too often we focus on the newest example of a genre, the latest technological advance, and we forward a myth that each new change constitutes a more advanced form of discourse….” Significantly, Cover engages with TTRPGs as a distinct community, separate from the other forms of RPGs that followed. Additionally, Cover introduces some fundamental topologies that inform my thesis, stating that they represent “sliding scales rather than binaries.” First, she describes “the dual nature of fans as consumers and producers;” however, she notes TTRPG fans tend to reside somewhere in the middle of a spectrum rather than at opposite poles. Second, she proposes the designation of the community-oriented fan, opposed by the individual fan, with the latter having little or no contact with the gaming community beyond their gaming group, while the former actively participates in that community. Cover suggests that a foundation for how community-oriented fans, acting as constant encoders and decoders, drove the formation TTRPG style.

Shortly after the first TTRPGs began to become popular, Gary Alan Fine performed an ethnography of RPGs and recorded his findings in the 1983 monograph Shared Fantasy: Role Playing Games as Social Worlds. Fine participated in several sessions of multiple games, conducted personal interviews, and compiled a wealth of data on the people who play these games. He used his data to define the social structures and frameworks that form around TTRPGs. By playing with multiple groups near the dawn of TTRPGs as a hobby, the timing of Fine’s work casts it simultaneously as a useful secondary and a primary source. Concluding that TTRPG players fit the sociological definition of a subculture, Fine argued these groups had real-world social value, and they constituted a non-delusional form of a Folie à deux, or shared psychosis, as players and gamemasters constructed a shared escapist fantasy world. Fine’s field notes and interviews offer excellent insight into the players’ attraction to these games. He also engaged with individual groups and participated in some large gaming clubs, so his observations help explain the development of some vital elements of the TTRPG style. Fine’s work also helps to illustrate the drive for players to create and play in worlds they could shape control though Folie à deux. Furthermore, Fine describes the behavior and attitudes of some players that may help explain why women made up such a small percentage of TTRPG hobbyists in the mid to late 1970s. Moreover, though little direct data exists, anecdotal and photographic evidence suggests that the ethnic makeup of early players similarly lacked diversity. The ethnic and gender composition of these groups may help inform the creation and formation of the groups that played TTRPGs in their first decade of existence. Fine’s study and his participatory observations illustrate how one aspect of bricolage, namely the privilege of white men, contributed to early the TTRPG style.

Sidebar: A Note on Primary Sources

In this article, I take a slightly non-traditional approach to primary sources and methodology. I use the rule books that detail the playing of multiple TTRPGs as sources alongside fan publications to aid in understanding these games as part of developing the TTRPG style. These rulebooks offer crucial insight into the mindset of the creators and players of these games. Presumably, TTRPG rule books have been ignored for their primary source value because many early examples lack prose and narrative in favor of rules. Yet these rules laid the groundwork for the shaping of imagined places, offering understanding into the how and why these settings developed as they did. For this discussion, I will analyze the books for the original D&D, and its immediate successor Advanced Dungeon and Dragons (AD&D) including the three books of the original D&D boxed set (1974), Basic Dungeons and Dragons (1977) the AD&D Player’s Handbook (1978), and the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide (1979). Additionally, I will also examine the 1977 TTRPG Traveller, a science fiction game in the vein of Star Trek and Star Wars that represents one of the first competitors to D&D in the TTRPG genre, as well as the 1975 game Tékumel: Empire of the Petal Throne, created by professor M.A.R. Barker. Along with a handful of other games, derivatives, and supplements, I also reviewed the first one hundred and ten issues of Dragon magazine, the house organ of the company that created D&D, with publication dates of June 1976 to June 1986.

The level of detail in TTRPGs complicates study by requiring a level of intimate knowledge with the subject matter, making examinations difficult for those lacking such knowledge. This inside knowledge informs debate over the status of the RPG community, and specific RPG communities as subcultures. Though a concept like gaming capital does explain certain aspects of TTRPGs, like a person having more knowledge of a game assisting less experienced players, the term falls short of explaining player collaboration as imaginary world builders. Fans’ understanding of the details of TTRPGS lies at the root of a continually evolving cultural exchange of fictional worlds that make internal insight a vital component of RPG studies. These distinctions also serve as a boundary of the TTRPG subculture. However, this knowledge lacks universality because a fan of one game may have little or no knowledge of another, allowing for cliques formed around a single game, or a series of interrelated games. This insider knowledge played a role in constructing the early TTRPG style, and as we shall see players’ usage of Tolkien, Howard, and other inspirations contributed to their own biases to develop a style that favored white men. These tropes make defining a historical period for the early TTRPG style challenging as many of its elements like Eurocentrism and colonialist language remain entrenched in the hobby in 2021. However, I shall primarily confine my study to the years from 1974 through the mid-1980s.

By this Pen, I Rule: The Style of Fictional Worlds as a Response to the Long Sixties

To understand the formation of the early TTRPG style and the community-oriented fans who continually received and re-encoded this style, the demographics of early fans prove vital. To create fictional worlds, gamers used the tools and knowledge they had at hand. Most early TTRPGs presented male-dominated and Eurocentric settings, hardly shocking given that the players and creators of wargames, and thus early RPG’s, were almost exclusively “white, male, middle-class American youths.” Early enthusiasts took a great deal of inspiration from the works of authors like J. R. R. Tolkien and Robert E. Howard, tales similarly rooted in Eurocentrism. Tolkien’s Middle Earth and Howard’s Hyborian world present settings where the European analog rests on the west coast of an ocean, while dark and mysterious analogs of Africa and Asia lay to the south and east in an Occidental-Oriental relationship.

Meanwhile, Howard framed his setting as a lost age of Earth where he could spin tales in equivalents of Europe, Africa, and Asia without the need for historical research or fear of anachronisms. These choices influenced D&D and its variants as both D&D’s Forgotten Realms setting and the world of Golarion, the setting of the D&D variant Pathfinder, both follow Howard’s model and demonstrate the continued pervasiveness of European equivalents as default settings. Seemingly innocent choices like these made Europe and people who looked like Europeans, the default model for fantasy TTRPG settings. Each of these settings makes a statement by situating a European equivalent in a geographically familiar location, while an East Asian parallel resides in the far east, a land of jungles with dark-skinned inhabitants exists to the south, and a region filled with Arabian and Persian stereotypes borders the Africa analog. Such arrangements make orienting newcomers easier by giving them familiar thematic landmarks. From a storytelling standpoint, Howard’s Khitai, Pathfinder’s Tian Xia, and Kara-Tur in The Forgotten Realms comprise a blend of China and Japan with some traits from other parts of Southeast Asia, making it easy for players to reflexively recognize them as places “like” East Asia. However, these fictional places deployed stereotypes that established and entrenched a style that favored the white male players of these games with worlds where light skin and Eurocentric tropes were the norm, while presenting exceptions to these tropes as different and exotic. For example, advertising for the original Oriental Adventures supplement set in Kara-Tur (Fig .1) promised exploits “in the mysterious East,” marking “Oriental” lands a distinctly exotic in comparison to European norms. Therefore, difference and the placement of “the Other” demarcate how TTRPG fans made style choices during the hobby’s formative years. These tropes also shaped the way other women were viewed within TTRPGs.

Though some very influential women contributed to shaping early TTRPGs, their numbers remained small for several years as male bias formed a vital arm of the TTRPG style. Jon Peterson recounts how one commentator questioned what “women’s libbers think” of the shortage of meaningful and roles for female characters in D&D, to which Gygax responded that he “will bend to their demands when a member of the opposite sex buys a copy of Dungeons & Dragons.” An article in the third issue of The Dragon further highlights the way the TTRPG style initially framed women. “Notes on Women & Magic-Bringing the Distaff Gamer into D&D,” contained rules for adding female characters to D&D, which had previously only allowed for male characters. The new rules included switching the “Charisma” attribute to “Beauty” for females, thereby allowing those with an exceptional beauty score to use the “Seduction” spell, while “ugly” or “grotesque” females could make use of the “Horrid Beauty” spell to possibly scare weaker targets “to death.” These rules defined females characters by their appearance in ways that were not applied to male characters. Gygax also showed his awareness, and perhaps disdain, for gender issues when he noted in the AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide that in his world of Greyhawk “all player characters are freemen or gentlemen” and further that “the masculine/human usage is generic” as he did “not like the terms freecreatures or gentlebeings!” With the excuse of adhering to linguistic tradition, Gygax excised gender and race from intruding on his male-dominated, Eurocentric world. While some might question whether Gygax’s writing came as a result of blissful ignorance of alternatives to placing male and European norms at the center of D&D, on the next following page a list of “Government Forms” and another of “Royal and Noble Titles,” negates such inquiries. These lists include the definitions “Gynarchy– Government reserved to females only,” and “Matriarchy– Government by the eldest females of whatever social units exist,” along with several social titles taken from Asian cultures, including “Sultan, Bey, Padishah, Rajah, and Kha-Khan.” Therefore, the TTRPG style presented female characters, Asian titles, and female led governments characters as novel alternatives, not viable norms.

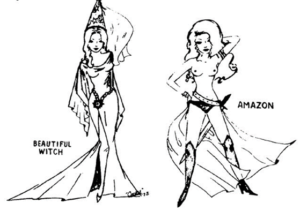

The TTRPG style also situated females as the Other in images and rules across a range of games. Further examinations of various books that comprised the original version of D&D only mention female characters in passing, a situation “Notes on Women & Magic-Bringing the Distaff Gamer into D&D” apparently sought to address. The first book of the original D&D set, “Men and Magic,” does include illustrations (Fig. 2) of a “Beautiful Witch” and a scantily-clad and topless “Amazon.” Aligning with Lakofka’s article such depictions further served to Other females by making them objects of desire, savage warrior women, or vile hags. Tunnels & Trolls, one of the first games to emulate D&D’s style in 1975, followed suit by offering a rearview sketch (Fig. 3) of a nude female warrior holding a spear in one hand and a severed male head in the other with the caption “Amazons! Very Tough Broads.” By 1978 AD&D indicted in its tables for character strength, different maximum scores based on race and gender, so a female halfling could not have a strength score higher than fourteen and a female dwarf could not possess a value over seventeen, the scores for males of all races had a higher maximum than their female counterparts. These gendered separations did not apply to any of the other physical attributes, though all of the attributes show different maximums and maximums for humans and each fictional race. Notably, every race assumed males as more physically powerful, never considering the possibility of a fictional race where females were stronger than males. The science fiction TTRPG Traveller departed from its fantasy counterparts and dealt with race and gender by offering the disclaimer-like statement “nowhere in these rules is a specific requirement established that any character (player or non-player) be of a specific gender or race.” However, despite this seemingly equitable language, players in-game coding of the TTRPG style still brought out some misogynistic behaviors as one of Fine’s respondents suggested that Traveller was not immune from acts against women that “would embarrass you, if you went out and did them now.”

During his time playing TTRPGs, Fine’s first-hand experience highlights another bit of bricolage that kept the early TTRPG style white, and male dominated. Fine observed that women, already hampered by having “few female or science fiction characters with whom” they could relate, also faced male-dominated groups where “fantasy rape,” sexual aggressiveness, and misogyny prevailed. Fine also noted that “in theory, female characters can be as powerful as males, in practice they are often treated as chattels.” Furthermore, he provides several first-hand examples of sexual assault or violently misogynistic behavior, concluding that such behavior could explain “why few females participate in these games,” and that “while it was not inevitable that the games will express male sexual fears and fantasies, they are structured so that these expressions are legitimate.” The early TTRPG Tékumel: Empire of the Petal Throne offered a few exceptions that superficially seem a bit more progressive for women than its counterparts. For example, the Yán Kór people on Tékumel came from a matriarchal culture with “sturdy men–and even stronger women.” Furthermore, the character creation section of Empire of the Petal Throne noted that “in Tsolyánu women are generally treated as the subservient sex,” but a female character could declare herself “Aridáni,” which denotes roughly “independent,” so that “she is then treated exactly like a man under the law, and she may become a warrior, etc.” Setting aside the reductive claim that a culture with “stronger women” would still view war as a uniquely male endeavor, these exceptions did not make Empire of the Petal Throne games immune from the rape and violence against women that players had injected into the culture. Fine describes in a first-hand account of an encounter with a group of female warrior-priests of the goddess Avánthe:

Tom yells: “I’m screaming at them ‘Stop and be raped, you goddamn women!”

After all six are killed, Tom, still excited, suggests: “Let’s get some jewels and panties.”

Later in the game when we meet another group of Avanthe [sic] priestess-warriors, Tom comments: “No fucking women in a blue dress [sic] are going to scare me… I’ll fight. They’ll all be dead men.”

Roger: Is that your definition of a woman, a dead man?

Tom: a dead man.

Fine further clarifies that “while Tom’s reactions are extreme, he is never sanctioned by others.” Naturally, nothing here suggests, nor do I imply that such extremes were the norm for every gaming group. I do, however, suggest a trend in early TTRPGs that Othered and marginalized certain groups, which influenced the demographics and style of TTRPG players. These examples illustrate how the early TTRPG style incorporated a level of misogyny and an assertion of control, as fantasy rape represented domination of the women of fictional settings. Thus, despite efforts by some games to appeal to women, the misogyny of the nascent TTRPG style likely contributed to low female participation. Demographic data remains scant, but the extant data suggests that significant numbers of women still did not play TTRPGs in the early eighties.

The conversation over how the TTRPG style that discouraged female players and made female characters objects for rape and discrimination continued in issues of Dragon magazine. The few female gamers playing D&D did not remain silent on these issues as they showed resistance to the early TTRPG style, even as they internalized its systems of control. A pair of articles in the July 1982 Dragon, “Women Want Equality: and Why Not?” by Jean Wells and Kim Mohan and “Points to Ponder” by Kyle Gray, acted as responses to the challenges that faced female gamers. Wells and Mohan suggested that the culture of gaming needed to change to consider that women “have a different outlook on, and perhaps a different approach to, life in a fantasy campaign.” They also noted that while some women might like to use D&D to do things they might not in real life, like “flirt” with strange men or “wear a low-cut dress,” they loathed the way the games products presented women a promiscuous by default. Wells and Mohan decried that the female miniatures used in the game “range from half-naked (possibly more than half) slave girls in chains or placed across horses or dragons, to women fighters dressed in no more than a bit of chainmail to protect their modesty.” Both articles also addressed the issue of female characters having a lower strength maximum that men, with Gray noting that “as a female player of Dungeons & Dragons, there is one thing that never fails to annoy me: the underestimation of the abilities of female fighters.” Wells and Mohan concluded that “women are, as a group, less muscular than men,” while Gray claimed, “it may be logical to penalize women in terms of sheer strength.” While conceding that “the strongest men will always be more powerful than the strongest of women,” Wells and Mohan suggested adjusting the maximum female strength to bring it closer to the male maximum. Alternatively, Gray claimed that women were “more agile” and that “it is a medical fact that the average female can withstand more mental stress than the average male”; therefore, female characters should receive a bonus to their Dexterity and Wisdom scores. Even as these women suggested how they could make things more equitable, they also demonstrated the pervasiveness of the early TTRPG style. In their closing Wells and Mohan note, “women players and those men who are concerned about women’s welfare will be left to devise their own methods of strengthening female characters, if they think that such strengthening is necessary.” The reasons Wells and Mohan presented for proposing, and not demanding, changes to female characters indicates how the few women playing TTRPGs could not see the profound systemic inequality of the games they played:

As with any other variant incorporated into a campaign, the only constantly important consideration is game balance. The D&D and AD&D game systems were designed with playability in mind, and the designers must sacrifice “realism” at times to achieve the playability and overall balance the game needs to have, to be of maximum benefit to the greatest number of players. Perhaps changes do need to be made in the game structure, and perhaps they will be– but no change for the sake of one improvement is worth the damage it might cause to other aspects of the game. D&D and AD&D are games and they’re supposed to be fun– not just for men or for women, but for everyone.

By admitting that “designers must necessarily sacrifice ‘realism,’” Wells and Mohan never considered the removal of the realistic, or “logical,” lower maximum for female strength to enhance the “fun” of “everyone” playing female characters. Additionally, they never expand upon their implication to detail how a female warrior possessing the same strength as a male might upset the game’s “overall balance.” Their conclusion reads as an apologetic assuaging the feelings of male gamers who might take offense at making their fictional worlds, and thus the TTRPG style more equitable for women.

Nearly 18 months later in a January 1982 Dragon article entitled “Dungeons Aren’t supposed to be ‘For Men Only’” contributing editor Roger E. Moore, acknowledged but vilified the penchant for rape as an in-game activity or storytelling device. Referencing Wells, Mohan, and Gray’s call for equality he describes how some players suggested that rape existed as a part of the “real and fantasy worlds,” before he facetiously inquires if men included “inflation, high unemployment, and racism” or other unpleasant topics in their games. Furthermore, he contemplated “what male gamers would think if their favorite male characters became part of a scenario reminiscent of the novel/movie Deliverance.” However, though Moore advised excluding rape from the game and suggested fairness by advising DMs, “if you have a gang of louts on some street corner insult all the women characters in one encounter, have another group insult all the men in another,” he also offered some guidance that exercised control over the female body.To prevent female characters from becoming pregnant, thus rendering them unable to go adventuring, Moore recommended a few workarounds. DMs could forgo rolling the dice to see if a female character became pregnant, instead allowing for “divine intervention… [as] Isis and Athena don’t want their female followers having babies all the time, interrupting their careers, etc.” or a DMs could employ a “Wish spell [to] prevent the possibility of unintentional future pregnancies.” Finally, a DM could “have a Magic-User invent a magic pill that permanently prevents conception unless the female characters want to get pregnant.” Moore’s suggestion offers a lot to unpack, from its suggestions of mechanisms to govern the female body, to the implication that female characters would naturally only follow goddesses like Isis or Athena. However, most importantly a great deal of effort went into a style that made the women in these worlds objects of control. Moore never suggests a rolls to determine male fertility or any application of game mechanics on male reproductive processes nor does he consider rules to determine if male characters might suffer from conditions such as impotence. Tellingly, the controlling aspects of the TTRPG style did not confine themselves to gender but also worked along racial axes.

Depictions of race reveal another key element of the style deployed in TTRPGs in their early years. Finding evidence on matters of race proves difficult due to the demographics of the majority of early TTRPG fans. Direct references to real world race are rare and as examples will demonstrate, the few that exists are often filled with Orientalist, and Eurocentric tropes. The omissions of characters of color who as primary heroes speak volumes through their absence. However, where we do find discussion or depictions of race, they are informed by the Eurocentric gaze of many early TTRPG creators who framed other cultures, peoples, and traditions not endemic to Europe as “mysterious” and useful for characters from European analogs to adventure in or conquer rather than as fully realized places that aren’t exotic to the people that live there. Alternately, games like Oriental Adventures fetishized honor, filial piety, katanas, ninja and other “Eastern” concepts and cultural artifacts. TTRPGs arose in the wake of the Civil Rights movement, making race a difficult subject to completely disregard for anyone in America, though the white middle-class dominance of the hobby may have made such matters a distant concern. While some scholars argue that in RPGs “the word ‘Race’ often has little do with the complex mix of cultural upbringing, color, parentage or geographical origins,” others argue that in many TTRPGs “light-skinned, Western European appearances are associated with good, while dark-skinned appearances are often associated with evil–effectively expressing notions of white supremacy.” As scholar Thomas Hahn posits “represented color difference is never ‘innocent,’ neutral, or without cross-cultural evaluative meaning.” The primary settings for D&D such as Blackmoor, and Greyhawk, tended to adopt a medieval European culture as a standard; though some exoticized Orientalist elements of certain Asian cultures did make it into early versions of D&D, such as Jinni, Samurai, and Asian martial arts, a faux-Europe proved more familiar and became the “norm.” As noted, emulating Europe did allow for simplified explanations, such as Tolkien’s Rohirrim being similar to Norman or Frankish cavalry, or that Howard’s Stygians were basically Egyptians. Though gross overgeneralizations, such explanations partially illustrate why Eurocentric ideas proved central to the creation of the fantasy worlds, and thus the style, of D&D and other TTRPGs. The writers of D&D did not lack awareness of other settings as an illustration in the AD&D Player’s Handbook shows a “European” knight flanked by a few priests whose grab and trappings indicate stereotypes of Meso-American, Chinese, and Japanese cultures. However, this picture contains the sole obviously non-Eurocentric depictions in the book. Rare exceptions certainly existed in early TTRPGs. M.A.R. Barker’s Tékumel: Empire of the Petal Throne used the dark-skinned and South Asian inspired Tsolyáni as the default culture, a decision influenced by Barker’s position as a professor of South Asian languages. However, the more frequent hard dichotomy between light and dark-skinned races flowed from long-standing prejudices that used color to evaluate a person’s worth. Perhaps, the most well-known example in D&D comes from the evil elvish race known as drow, described as “black-skinned and pale-haired” the drow “were cruel and selfish” elves driven underground by their light-skinned cousins of “better disposition.” Therefore, blackness represented evil as an entry in the Monster Manual explains, “drow are said to be as dark as [the surface-dwelling elves] are bright and as evil, as the latter are good” thus making a clear connection between darkness and evil opposed by brightness and good. Importantly, such ideas sent signals to people of color that white players could not or refused to understand, further alienating black, indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) from the hobby.

Though on the surface race seems a non-issue when examining early TTRPGs from some perspectives, deeper examination offers additional insights. Though Moore implied that games did not include real-life unpleasantries like “inflation, high unemployment, and racism,” the absence of overt racism did not veil systemic racism that contributed to the early TTRPG style. In the first one hundred and ten issues of Dragon, few depictions of people of color exist, though the exceptions are telling. Then as now, TTRPG fans enjoy translating characters from other works of fiction, such as films, novels, folklore, and comic books into a range of game systems. Therefore, many people of color depicted in Dragon came from the creations of others, and were not characters made explicitly for TTRPGs. Characters such as H. Rider Haggard’s Umslopoghaas, folklore hero John Henry, boxing champion Muhammad Ali, and comic book hero and Iron Man’s bodyguard James “Rhodey” Rhodes all received conversions into various TTRPGs in issues of the magazine. Additionally, Dragon issue 84 began a new section of the periodical named “ARES” to focus on science fiction content, and this segment often carried conversions of comic book characters to the Marvel Heroes TTRPG. Comic books by this time featured several BIPOC characters, yet, TTRPGs rarely incorporated people of color who were not from other media and original or converted white characters remained the norm. Often original characters of color only appeared in advertisements for modern or futuristic games like the post-apocalyptic TTRPG Twilight 2000 or the science fiction TTRPG Space Master. Yet even in the latter case, semiotic coding of color remained part of the TTRPG style as the dark-skinned character in a frequent Space Master advertisement (Fig. 4) appears offering tribute to the light-skinned woman before him. The Space Master advertisement was not alone in demonstrating problematic depictions of BIPOC characters as advertisements for TSR products and games (Fig. 5-7) turned a corner in the early eighties and began featuring female players but not people of color, further encoding a white-centric style.

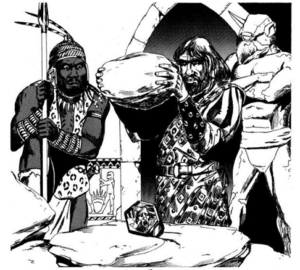

The few exceptions of depictions people of color that existed in early articles and games, also suffered from problematic harmful stereotypes embedded within the Eurocentrism of the TTRPG style. The September 1981 issue of Dragon featured an illustration (Fig. 8) from a D&D adventure that had won first place in the magazine’s first contest for adventure design, which asked fans to write an original dungeon adventure. In the image, the black character stands by passively, clad in a leopard skin and holding a spear while his white companion clad in heavier European inspired armor prepares to smash a gem the holds the soul of the villain in the adventure. The illustration makes the black character inert while also evoking imagery of a “noble savage” sidekick.

Another indicator of the way the early TTRPGs handled race comes from Tunnels & Trolls. The game’s spell list includes a spell named “Yassa-Massa” usable on “previously subdued monsters/foes,” allowing the caster to “permanently enslave” their enemies. While I could not find any academic studies of the exact percentages of the ethnicities of those who played TTRPGs in the hobby’s first decade, the combination of the Minstrel Show-like name of the spell with the word “enslave” speaks to how early TTRPGs made BIPOC the butt of casual and insensitive humor. Such humor reflects the casual nature of systemic racism in the late 1970s and early 1980s, while also supporting Peterson’s claims that early TTRPG creators were predominately white and lacked many BIPOC voices to counter ingrained racism. These depictions reinforced a style which signaled that these games were for whites only, or that people of color were sidekicks or chattel. Arguments that advertisers and designers only sought to cater to the fan base that played these games perpetuate the cyclic ideas that kept, and continue, to keep marginalized people from inclusion in a range of cultural activities.

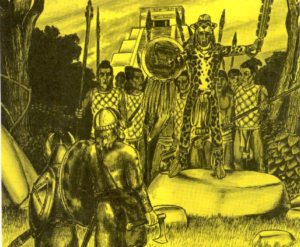

Some in the TTRPG community did eventually begin to recognize the need to have people of color contribute to the depictions of people from non-European cultures and by 1983 such articles began to appear in Dragon. Kim Mohan, who became editor-in-chief sometime after writing her article on equality three years before stated: “the roots of fantasy role-playing are planted in the soil of northern European culture, but that doesn’t mean that your campaign can’t branch out to explore of the climates and other social systems.” She further suggested that “DM’s and players alike should find it interesting, to say the least, to deal with a situation and a society that aren’t typical of the circumstances in which most FRP [Fantasy Role-Playing] adventures take place.” The early TTRPG style had made such adventures unusual up until this point and as noted “unusual” became a dog whistle for non-European. The adventure “Mechia” written by Gali Sanchez and touted as an “adventure to introduce the player characters to a new culture” presents an encounter with an Aztec-like civilization right down to a city named Tenocatlan that sat on the marshes of a lake much like the real Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. The piece also used the Aztec deities Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca and even lifted the name of the last Aztec Emperor as the moniker of the adventure’s fictional emperor and villain, Cuauhtémoc. However, the TTRPG style still showed its influence as the adventure establishes a “White Savior” narrative that calls on the Eurocentric player characters (Fig. 9) to prevent Cuauhtémoc and his Jaguar priests from turning more of his subjects into werejaguars and causing a shift in the deific balance of power from Quetzalcoatl to Tezcatlipoca. As before, Dragon encoded a style that presented “Europeans” as normal and other cultures as different and exotic. Even as the community made efforts to alter the early TTRPG style, deep-seated institutions of Eurocentric dominion refused to give way.

As the eighties progressed, Dragon continued to work on its offerings of other cultures. The story “Mzee” in the June 1984 issue, by African American fantasy and Science Fiction author Charles R. Saunders, presented a tale from an outspoken critic of racism in fantasy. The story gave Dragon a piece from the perspective of a person of color, with black characters, an Afrocentric setting, and, most importantly, no characters from European equivalents. Saunder’s story signaled some change, but the TTRPG style encoded biases that remained well past the eighties. In “Representation and Discrimination in Role-Playing Game,” Aaron Trammell argues that “discrimination of women and people of color is still common place in today’s TTRPG community, if in forms that are sometimes hard for the unaffected to notice.” These sentiments demonstrate that the style that developed in the early years of TTRPG’s rested on the foundation of systemic oppression in mainstream American culture despite players’ attempts to escape reality, such insidious roots do not shift or vanish easily. Understanding the prevalence of real-world issues like gender and racial equality helps reify the seemly disparate pieces of bricolage that set the tone of the worlds that projected the early TTRPG style.

Gaining Experience: Concluding Thoughts

The control fictional worlds gave players unifies the bricolage of the early TTRPG style. Unsavory acts such as fantasy rape or enslaving foes via magical means, gave young white men fictional spaces where they held extensive, and in some cases near limitless control. The actions of TTRPG players at the dawn of the hobby do not imply overt racism or misogyny in every case, but they do suggest a systemic and pervasive element of style that shaped the early TTRPG community and industry. As game designer Tony Bath opined, “[T]he advantage of a mythical background was that ‘there are no restrictions save those that we ourselves impose. You can indulge in any mixture of types and races, mix medieval and ancient, do as you please within the structure of your design.’” Contrary to the suggestion of “mixing types and races” the early TTRPG style kept white men as the focus of “the structure” of these games. The games “impose[d]” real-world “restrictions” on the imaginary races and marginalized groups in these games that otherwise lacked any external limitations. TTRPGs entered the marketplace at a vital juxtaposition of events, as the social, cultural, and political changes of the Long Sixties still reverberated throughout the world. The conflict in Southeast Asia, the Civil Rights Movement, the battle for the Equal Rights Amendment, and numerous other events of the Long Sixties challenged the longstanding status of middle-class white men in America. These men sought an escape from a world that disrupted their dominant position and threatened privileges they often lacked the tools, or desire, to evaluate. The 1960s and 70s (into the early 80s) saw a rise in the popularity of a range of escapist entertainments, particularly in the fantasy and science fiction genres. This search for other worlds made “the early 1970s…undoubtedly the time when the fantasy genre enjoyed its greatest prominence to date and reached the largest number of consumers.” Many of these young men turned to the newly minted TTRPG industry that gave them unprecedented latitude. The community reencoded the first TTRPG with an array of additions, modifications, and entirely new games. In doing so, TTRPG fans created a distinctive sub-cultural style especially in the ways that significant social or political events influenced the semiotic codes that TTRPGs projected. Many aspects of bricolage that formed this style persist in the TTRPG community in the 21st century. Though these male-centric and Eurocentric qualities led to some traits of the TTRPGs style that modern readers might find cringeworthy, TTRPGs also offered pathways to explore the imagination and have fun in an environment that lacked real-world consequences.

The subcultural style established by early TTRPGs, while resistant to change, continues to evolve beyond the less admirable traits of the early TTRPG style. The 3rd Edition of D&D that launched in 2000, included prominent images of heroic characters of color but also failed to address deeper systemic issues. A new crop of twenty-first century games explore avenues that escaped early TTRPG fans–that in games that permit fire-breathing dragons, magic, and amazing feats of daring-do, the elimination or modification of past cultural norms should seem no more out of place than a ravening horde of fictional beings, or a talking, chess-playing cat. Recent games push new boundaries around the core elements of TTRPGs by allowing them to grapple with difficult topics in a place with lower stakes than reality. TTRPGs like Harlem Unbound, by African American game designer Chris Spivey, reframe the popular ideas of racist author H. P. Lovecraft, an industry staple since the Call of Cthulhu TTRPG appeared in 1981. Recently, crowdfunding campaigns for games like Jiangshi: Blood in the Banquet Hall, Into the Motherlands, and Coyote and Crow, among others, have challenged the dominance of games made by and for a hegemonic demographic. Importantly, these games are part of a crop of games created by teams of developers led by, and consisting of, members of the marginalized communities they depict. As in wider society, new voices work to re-encode the TTRPG style. However, the maker of the world’s most popular TTRPG, Wizards of the Coast (WotC) still struggles with matter of race. In 2020, Orion Black, a black, non-binary writer working for WotC left the company and alleged others at the company stole their ideas and negated their suggestions to adjust content that might prove offensive to marginalized communities. WotC apologized and promised to work toward more diversity but found itself under scrutiny from the TTRPG community in early 2021 when freelance writer Graeme Barber requested his name be removed from an adventure he had written for WotC, after he noted, “The plot was 80% missing and problematic colonialist language and imagery had been inserted.” Barber further explained, “Colonialist language and imagery around the Grippli was inserted as well, moving them from being simple and utilitarian with obvious culture and technology to being ‘primitives’ who ‘primitively decorate’ their thatched huts with crab bits.”Barber, “What Happened?”[/ref] Barber’s disappointment reverberated in the TTRPG community and highlighted how the white men who make decisions at WotC and many white fans fail to understand the issues BIPOC players have with such depictions. These oversights and negations keep the worst parts of early TTRPG style alive and well over forty-five years after the hobby’s inception.

The early TTRPG style and the TTRPG subculture, based themselves on the cultural norms and ideas of the middle-class, white, American male. The systemic institutions that these men lived in influenced the fictional worlds they designed. TTRPGs still have issues, but the cooperation the community thrives upon helps it work through its issues if fans open themselves to understanding the darker elements of their hobby and discuss how to move past them. When faced with issues concerning “non-white people” or ideas of cultural appropriation, some fans still become defensive and vitriolic in opposing the notion that the TTRPG community suffers from or needs to address these issues. The fans often make Appeal-to-Tradition fallacy arguments that suggest that what has worked for them does not need fixing. However, other fans demonstrate that they can actively engage and exchange information with a community that challenges persistent systemic inequity rooted in the formation of the TTRPG style. The early style grew around a community looking to escape the pressures of a drastically changing world, but that community also nested within larger structures of marginalization that necessitate introspection and awareness that gamers did not, or chose not, to see. This style reflected real-world structures and held such sway that even the few players who represented marginalized groups often placed fun and “realism” over equitable rules. The collaborative nature of the TTRPG style caused it to echo the biases of its creators and the properties that inspired them. Despite statements eschewing the inclusion of unsavory elements like “inflation, high unemployment, and racism,” the privilege of the fanbase’s majority flowed into their mythical spaces and implicit biases prevented them from contextualizing the full scope of the unpleasant elements that had entered their games.

–

Featured image “Master of the Gamblers” is from Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Master_of_the_Gamblers_-_Dice-players_and_a_bird-seller_gathered_around_a_stone_slab.jpg. Public Domain.

–

Stefan Huddleston is a Lecturer in the History and Humanities Departments at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. He specializes in the histories of marginalized groups, pop culture history, representation in media, and modern Sub-Saharan African history.