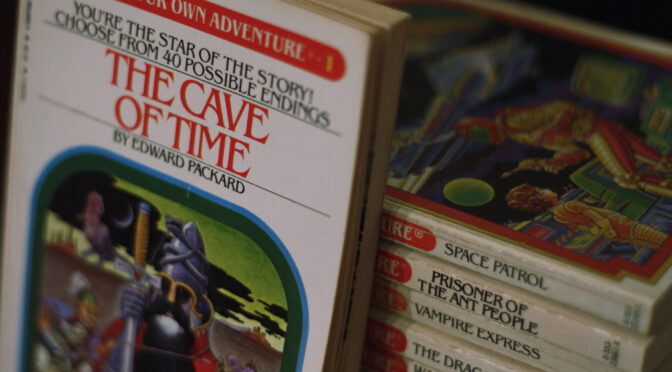

The gamebook is a genre of analog interactive fiction that originated in the US and in the UK in the 1970s and expanded internationally to produce thousands of works and sell millions of copies in the 1980s and early 1990s. The Choose Your Own Adventure series dominated the gamebook market for children and tweens with simple branching stories, and it became the most iconic line of them all. In the 1980s, writers started pairing branching structures with game mechanics featuring combat, skill tests, and inventory. Fighting Fantasy and Lone Wolf emerged as the dominant series of this variant, bringing gamebooks to older tweens and teenagers. The market for gamebooks contracted dramatically in the mid-1990s, possibly because of competition from video games. The transition looked catastrophic due to how massive the gamebook craze had been, but contrary to popular perception the form didn’t die.

Some of the most popular series, like Choose Your Own Adventure and Fighting Fantasy, went out of print for a couple of years, changed publishers, and started publishing a mix of updated reprints and new texts. In one shape or another, they continue to exist to this day. The current publisher of Choose Your Own Adventure declares the sale of 16 million copies since 2006, which seems a far cry from editorial extinction. New series surfaced even in the nadir years (Give Yourself Goosebumps released 42 volumes between 1995 and 2000), and continued to emerge in the 21st century. From the early 2000s, now-adult original readers also started supporting a market for gamebooks. The presence of an adult audience led to the creation of gamebooks that could be longer than the originals (with over 1,000 sections), could be experimental in form and style, could deal with mature themes like sex, drugs, gore, and even the workplace, and could sport much higher production vales (with hardcovers, boxed sets, custom dice, and color maps).

In this sense, the gamebook has done much more than surviving. While it continues to offer entertainment for young readers, it has also matured to include sophisticated works that adults can access through traditional publishers, print-on-demand, and crowdfunding.

Early studies of interactive fiction focused heavily on digital texts and paid little attention to gamebook series that had sold millions of copies and shaped the imagination of a generation. When these scholars discussed gamebooks at all, they framed them as rudimentary parallels of digital works and erroneously equated the Choose Your Own Adventure series with the entire gamebook form, leading to inaccuracies and distortions. As Infocom-style interactive fiction became of interest only to a tiny community of readers-creators, such parallels with gamebooks disappeared too.

They were not replaced, however, by a robust stream of studies on the gamebook. In the last decade, a short section in a book by Salter, three highly theoretical articles by Wake, a mathematical analysis by D’ Andre et al., and part of an article by Altice, are possibly the most significant academic contributions to our understanding of gamebooks. The time may have come, then, for a serious consideration of this expressive form.

In this article, I attempt a classification of the fundamental traits of the gamebook. Given how limited and scattered the study of this subject has been, I hope to present a useful framework for the understanding of the gamebook as a technology for interaction and sense-making. I am not attempting to retell a history of the form from its antecedents of the 1930s and 1940s to the present, nor am I drawing a typology that could cover every gamebook ever written. Given the size of the subject matter, these aims would be futile at best. Rather, based on the hundreds of gamebooks I have read in the past 35 years, I will break down this cultural artifact into its main fundamental components and describe how each has typically worked. I will draw most of my examples from gamebooks of the 1980s and early 1990s. That was the time when most gamebooks were published and enjoyed the largest print runs, so any consideration of typicality must be grounded in that era. I will also compare trends from that period with works aimed at adult readers of the 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s. This bifocal approach is meant to delineate broad and influential trends without ignoring the variety of eccentric paths that have also been attempted.

Moreover, while some aspects of the gamebook are medium-independent (allowing me to rely partly on scholarship about digital fiction), I also emphasize the unique affordances, limitations, and creative opportunities that the gamebook derives from its materiality. It may be precisely thanks to this materiality that the gamebook has started to thrive again as part of a current “revenge of the analog” (Sax). Visually rich video games may have replaced parser text adventures, but the experience of reading a gamebook is so different from digital gaming that these artifacts continue to retain their own individual appeal.

Definition

I define a gamebook as a narrative printed on paper and divided into sections connected by links. By following the links, the reader experiences alternative narrative paths which lead to multiple endings. Consequently, the most minimalistic gamebook conceivable could not have fewer than three sections: a starting section and two endings connected by a single branching point. While broad by design, this definition still distinguishes gamebooks proper from a variety of other texts. For example, it excludes instructional books such as those in the TutorText series (1958-1972), whose branching structure is meant to quiz the reader and not to advance a story. The definition also excludes linear stories in which the reader must solve puzzles and riddles before being allowed to proceed on a single, unbranching storyline.

Finally, I focus my analysis to book-length gamebooks. While shorter branching narratives printed in magazines or stapled booklets exist, it is in the longer, bound form of the book that this kind of fiction has mainly impacted its audience.

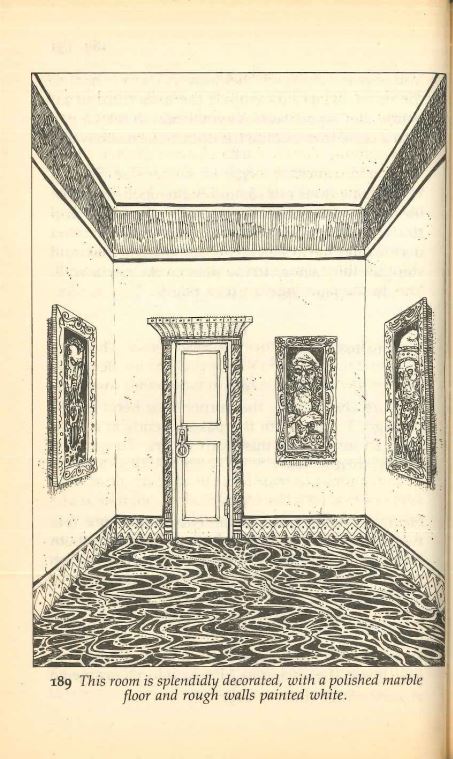

Text

By text I designate the content of each section of the book. In an overwhelming majority of published gamebooks, this content is delivered in prose and is supported by black and white illustrations. In most cases, these illustrations simply enhance the atmosphere and sense of place of the story. Occasionally, the illustrations may include clues that the reader must decipher, becoming part of the main text too. In a small minority of gamebooks, the illustrations take up most of the physical space of the work and contain most of the indications needed to navigate the book. Stephen Leslie’s Three Men in a Maze (1977) is a case in point, being mainly an illustrated maze.

Gamebooks can also express their content through the language of comics. Examples include Italian stories featuring Disney characters (from 1985), stories in the short-lived Diceman magazine (1986), the Dudley Serious graphic novels by O’Connor – Cooper (1990-1991), Jason Shiga’s Meanwhile (2010), and Ewing – Espina’s You Are Deadpool (2018).

I am not aware of any tradition of gamebooks written in verse. As gamebooks represent an innovative approach to a pre-existing technology (the book) and to a well-known type of expression (fiction), they naturally show a certain degree of remediation, a process by which new artifacts tend to refashion elements of their predecessors. For example, following the tradition that most fiction has been written in the third person and in the past tense, the first known gamebook (Consider the Consequences!, 1930, by Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins) adopted precisely this perspective. Like most fiction up to that point, the story of Consider the Consequences! is framed as having occurred already and as involving someone other than the reader.

Gamebooks of the 1970s and early 1980s attempted different approaches to the grammatical construction of the text, gradually departing from millenary conventions of fiction. The Tracker series of the 1970s adopted the first person (which also has a literary tradition) and the classic past tense, making each text sound like a sort of autobiography. See this passage from James and Allen’s The Black Dragon (1973), section 20:

The room looked like a library. I was firmly bound to a chair, and my wrists and ankles were tired. I could move my hands a little and using my feet, I could edge the chair along the floor towards the desk. I could either try to knock the receiver off the hook and phone the police, (22) or I could try to break the lamp and use the broken glass to cut the rope. (27)

In the mid-70s, the second person and the present tense were adopted in the Adventures of You series by Packard and Montgomery, which later morphed into Choose Your Own Adventure. The fact that that was also the perspective adopted in role-playing gaming (“you enter a dark room…”) may have contributed to the propagation of the idea, especially in later series influenced by RPGs such as Fighting Fantasy, Endless Quest, and Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. Once the major series above adopted the second person and the present tense, there was no turning back. No other perspective has ever been as popular, nor has it rivaled it in terms of immersive positioning of the reader within the story.

The second person, obviously, mobilizes emotional responses at a very immediate and direct level. The text is literally talking to you, yes, YOU!, the actual person on the other side of the page. The present tense, meanwhile, creates the illusion that the adventure is taking shape at the same time as you make your decisions, helping you overlook the fact that the text has already been written and is inalterably printed.

Once this perspective started to dominate, different approaches became rare. The third person survives mainly in gamebooks based on specific IP’s. The series You Choose: Scooby-Doo (fourteen books, 2013-2017), for example, allows the reader to select the actions taken by single characters, small groups, or the entire team, and the narrative is presented in the omniscient third person. If immediacy is lost in the process, the choral feel of the original cartoons is retained, and the parasocial pleasure of “hanging out with the gang” is gained.

Gamebooks in comic / visual form may use the second person in verbal sections addressing the reader, but usually organize their illustrations in the third person (with the protagonist visible in the panels), and/or in the first person (showing the scene from the perspective of the protagonist). The first group includes structurally traditional comics to which the branching device has been added (like You Are Deadpool). The latter group includes branching comics in which the protagonist is mainly invisible, and the panels are shown from the protagonist’s visual angle, like in Gaska – Thomas – Chiola’s Eight Grade Witch (2021). A large group of first-person visual gamebooks is in the series Ace of Aces series (from 1980) and Lost Worlds (from 1983), depicting duels between combat pilots and fantasy characters, respectively. The first and third perspective can also be combined within the same story, as it was frequent in the comics of the Diceman magazine (by Pat Mills and others, five issues in 1986).

When it comes to positioning in text-based gamebooks, grammatical and formal choices are only the beginning. The text must also decide whom the reader will get to impersonate, and to what degree of granularity that avatar will be described. In rare cases like You Choose: Scooby-Doo books, the reader is not one of the characters in the book. Usually, though, “you” is the protagonist, so: who is this you, and what do we know about them? The most successful gamebook series of the first generation show the approaches that have remained dominant to this day.

The Choose Your Own Adventure series has taken great pains to ensure that most of their protagonists are generic and neutral, so that many kinds of children and tweens can identify with them. The English language allows a relatively easy construction of grammatically epicene characters, which isn’t always the case in other languages. When the Choose Your Own Adventure series expresses a protagonist’s gender clearly, it is often in sport-themed books like Edward Packard’s Soccer Star (1994) or R. A. Montgomery’s Track Star! (2009), where the gender of the athletes cannot be concealed. The protagonists are usually white or racially ambiguous. They are in the tween / teen / young adult range (which a child can identify with or aspire to), and they have a high degree of freedom, allowing the reader to enjoy liberating fantasies of agency.. In the last couple of years, the series has been moving in the direction of more diversity, with the frequent inclusion of explicitly female and non-white protagonists.

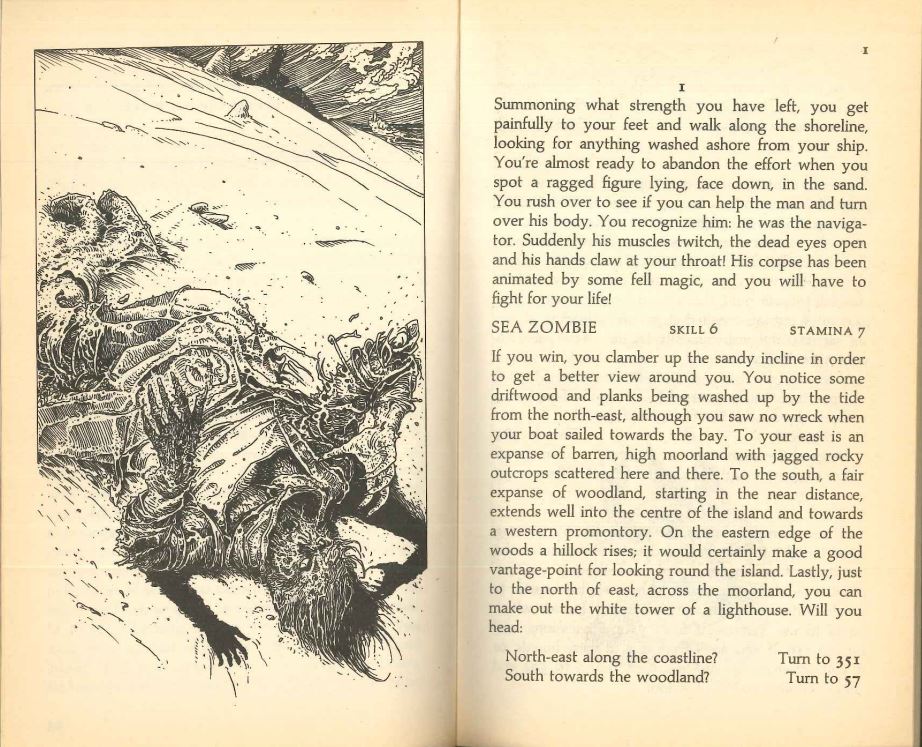

The series Fighting Fantasy has traditionally favored indeterminacy even more than Choose Your Own Adventure. A Fighting Fantasy story describes the protagonist in terms of profession and skill sets, but does not typically commit to a name, gender, or physical appearance. The illustrations on the cover and in the book are consistently constructed from the point of view of the protagonist, showing the enemies the hero is going to face, the characters they will interact with, and the locales they are about to explore. This solution increases the sense of immersion and excitement while retaining plenty of opportunities for identification.

Other popular gamebooks committed to individually and highly defined protagonists, especially when targeting role-players. For example, the first Endless Quest book (Rose Estes’ Dungeon of Dread, 1982) clarifies that

you play the part of a human fighter. As an adult, you stand 5’9″ tall and weigh about 150 pounds. You are smart and have survived many adventures using little more than your wits. You are well schooled in the use of weapons, and are a powerful opponent. You carry a sword and a dagger, and wear a long-sleeved green tunic over leather breeches. Fine leather boots guard your feet. A long green hunter’s cloak protects you from the cold. You carry flasks of oil, a tinder box, a length of rope, and other gear in a leather pouch tied to your belt, and food and water in a sack slung over your shoulder. (1)

All following Endless Quest books included similarly detailed protagonists, favoring male heroes. Highly appreciated series like Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Adventure Gamebooks and Lone Wolf also featured individualized male protagonists. Series featuring explicitly female protagonists have been less common, have targeted female readers, and have either been romantic in genre or have tended to include an element of romance.

In more recent times, some educational gamebooks have allowed young readers to explicitly play characters of different genres, like in Elizabeth Raum’s The Revolutionary War (2010), where the reader can play as the daughter of a militia captain, as a male American patriot, or as a male British loyalist. The involvement of adult readers has also allowed more varied perspectives. Examples include Ryan North’s To Be or Not to Be (2013) and Romeo and/or Juliet (2016), which feature male and female protagonists and even allow the reader to switch identity (and therefore gender) along the way.

Game Mechanics

Despite the name, game mechanics are not a core trait of the gamebook, which is why they were not included in the general definition. At a high level, of course, all forms of branching fiction can be said to have some elements in commons with games. Both types of expression have explicit and implicit rules, require active participation, and involve variable outcomes which are assigned different values. In all gamebooks, such outcomes are the endings. Just like a game can end in victory or defeat, a gamebook can lead the reader to triumph or catastrophe, especially in the case of goal-oriented stories. And like some games (not all) can end in a draw, so some gamebooks (not all) include ambiguous and inconclusive endings.

More strictly speaking, though, a gamebook includes game mechanics only when it requires to perform actions other than reading and turning pages. These actions may include rolling dice or generating other random values (like flipping a coin or checking the time of the day), collecting and spending resources, keeping inventory, customizing a character with skills and abilities, or adjusting numerical stats. The trade-off is always the same: the more game mechanics are in a gamebook, the more demanding the explanation of the rules and the more specialized the audience becomes.

The agency factor is key here. A gamebook incorporating game mechanics does not tell the same story in more steps; it tells more story. Game mechanics generate events that take place in the storyworld of the book even if they are not explicitly mentioned in the text. Many gamebooks, for example, include rules for combat. When the reader reaches a fight, the text does not describe all events of the battle but simply furnishes the necessary stats. By following the rules of the system (like rolling dice, applying modifiers, and alternating rounds of attack and defense), the reader then creates a flow of fictional events that fully belongs to the story.

In the process, the experience becomes unique. Every copy of the gamebook presents the same descriptions, the same rules, and the same stats. And yet, as I approach an encounter, my hero may have been weakened by previous battles and their chances of success may be low. Somewhere else, you are reading the same gamebook, but you made different choices, you were maybe a little luckier, and your hero enters the encounter at full health, which is a very different narrative situation! When you resolve your battle and I resolve mine, distinctive sequences of events are likely to occur. If my hero dies, I experience a tragic ending that is not mentioned in the text and that you may never get to see.

The process also increases replayability because it allows the reader to attempt different strategies when returning to the same scene. This element is particularly prominent in gamebooks with large inventories of skills, items, weapons, and upgrades that be combined in different ways each time, as in Michael J. Ward’s The Legion of Shadow (2012).

Keeping track of stats is also designed to be done by writing in the book itself, which makes the connection between reader and artifact even more visceral. The text I am navigating may have been printed in many thousands of copies, but my notes and the records of my choices have made my copy unlike any other in the world, just like my adventure was the resultant of my own performance and no one else’s.

Sections

Sections are the narrative units of the gamebooks. They are sometimes called lexias or nodes in media studies, and entries or paragraphs in common parlance. They are the individual portions of the text framed by links, or by the beginning of the work, or by its endings. Sections contain the text, but they are not the text itself.

Each section of a gamebook must be clearly and unambiguously marked to allow navigation. By far, the most common way to do so has been to number each section sequentially. More rarely, gamebooks have employed strings of letters (AAA, AAB, AAC…), combinations of letters and numbers (A1, A2, A3…), or other labels. The end of a section must be clearly identifiable also.

Gamebooks have often implanted their mode of organization on the tradition of partitioning books by page and chapter. The early gamebooks Consider the Consequences! and Treasure Hunt (1945, by Alan George) employ this method, and when offering options to the reader they direct them to this or that page. The method is so simple and intuitive that is has been almost universally adopted in gamebooks for younger readers, and most notably in the Choose Your Own Adventure series. At the same time, the method has its shortcomings. If a section ends in the middle or in the top half of a page, for example, the space below cannot be utilized. It may contain an illustration, but it cannot start a new section.

Starting with Rick Loomis’ Buffalo Castle (1976), the publisher Flying Buffalo divorced the borders of the page from the framing of the narrative by placing multiple sections in each page of their solo modules for the Tunnels & Trolls RPG. Each section containing only a short text, this solution allowed the publisher to make an efficient use of space and save on paper. Later, this method was adopted by popular lines of gamebooks like Fighting Fantasy, Lone Wolf, The Way of the Tiger, and many more. Now a numbered paragraph could be as long or as short as its content required, and it could start and end in almost every part of the page. A high number of narrative units could be packaged within the book, increasing complexity and challenge. For example, The Warlock of Firetop Mountain (1982) by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone, packed 400 narrative sections in only 163 pages. More sections mean more places to explore, more interactions to navigate, more decisions to make, and a deeper sense of immersion. Similar options are available in gamebooks in comic format, with some being labeled by page (starting with Italian Disney stories published from 1985), and some by panel (as in the Diceman comics of 1986).

Gamebooks being printed goods, care is also taken that the partitions caused by the limits of the page do not interfere with the partitions of the text. Mistakes in this sense can make a gamebook challenging to navigate. In Keith Martin’s Island of the Undead (1992), for example, the choices offered at the end of section 1 wrap around the edge of the right page. Only the first two options are visible at the bottom of page 1, without any indication that three more choices are available in the following one. As the end of the page appears to mark the end of the section, those last choices are likely to be missed.

The Locked Room

The “locked room” is a special kind of section with no links leading to it, making it impossible to reach it without cheating. It looks like a gamebook section, it reads like a gamebook section, and yet the only thing that makes it belong to the gamebook ss its being printed together with the other sections. It may take completing and mapping the whole book, before one realizes that a certain section has no links pointing to it.

In some cases, the locked room is simply generated by mistake: a link was messed up in the writing or editing of the book, and now that section is severed from the rest. In other cases, the locked room is inserted by design. Its role is akin to that of an Easter Egg in video games, and it provides a special satisfaction to those happy few who will find it. The anomaly of the locked room also lends itself to generate moments of surreal humor. Such take was already present in the earliest locked room of which I am aware, in Rick Loomis’ Buffalo Castle (1976), section 19E: «It is impossible to get to 19E. You have cheated. You are instantly vaporized by the DungeonMaster!». Another example is in section 42 of Dave Morris’ Knightmare (1988):

You cross the energy-charged floor of the Vaarkan spaceship and walk to the command console, where Zlissgath, a Venian navigator, is waiting.

‘You should not be here,’ he hisses. ‘You are wearing silly helmet. I think you lost.’

You are lost. You’ve wandered into the wrong adventure!

In the Choose Your Own Adventure book Inside UFO 54-40 (1982),Edward Packard employed a locked room in a highly creative way. The section is paired with a large two-page illustration, which the reader can’t help but noticing while flipping through the pages during normal navigation. The more the reader becomes aware of that visually evident section, the clearer it becomes that there is no way of getting there. The section describes a utopian planet called Ultima, which is mentioned several times in the book. The opening of the section clarifies that the passage’s inaccessibility was not an oversight: «You did not make a choice, or follow any direction, but now, somehow, you are descending from space – approaching a great, glistening sphere. It is Ultima – the planet of Paradise» (101). Cheating turns out to be the only way to “beat” the book and reach the best possible outcome.

Finding the locked room is construed as a success also in Neal Patrick Harris’ Choose Your Own Autobiography (2014): «Congratulations! You have found the hidden page. No other section leads to this one, and it’s impossible to imagine anyone violating this book’s explicit instructions by casually flipping through it out of sequence. So, how were you able to find it? Because you, sir or madam, are a rare breed of individual. You are diligent and intrepid».

A much more ambitious use of locked rooms is in the gamebook for adults Life’s Lottery (1999) by Kim Newman (Short). The book has 300 numbered sections, of which nine have no links. What is unusual is not just the number of locked rooms but the fact that, if they are identified and read in the order of appearance, these sections form a secondary narrative that casts a different light on the events in the branching tree!

Links

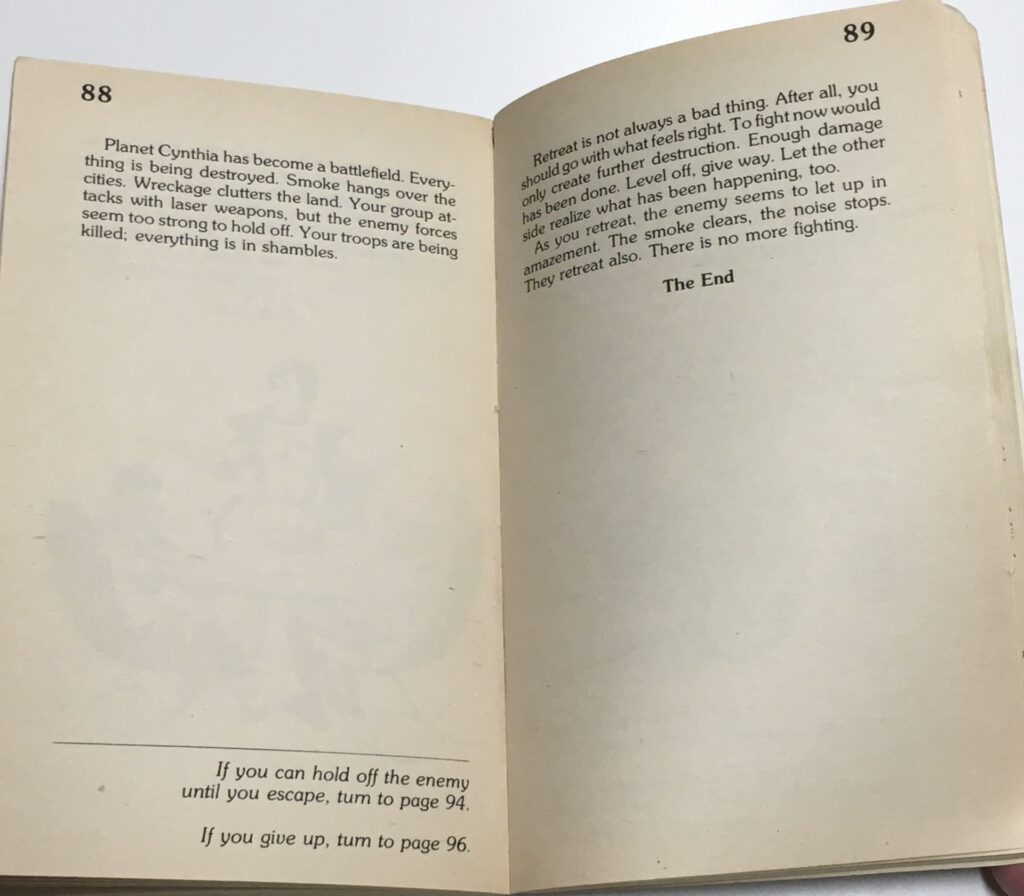

The links are the instructions that connect the sections and allow the story to progress in different directions. Links usually take the form of if / then instructions directing to specific sections. Typically, the links are placed at the end of a section, in the form of a menu of options such as: «Save Gertruda! Turn to page 100. Save yourself! Turn to page 105».

In Avatars of Story, Ryan described such links as «blatant» and partially dismissed them as «too legible», because «they give the reader a preview of the content of the target lexia».. In actuality, rarely does a gamebook let the reader decide what will happen on the other side of a given link. In the example above, there is no certainty that I will be able to save Gertruda just by turning to page 100. All I can expect that my character will try to do so, but the “blatant” link can still ambush me with many sorts of dramatic plot twist. While making a choice, we don’t know if that action will occur at all, and with what consequences. Despite what the name of the Choose Your Own Adventure series says, in gamebooks one doesn’t really get to choose their own adventure, but only the protagonist’s next attempted action.

The opacity of the gamebook link does not have to contradict the reader’s overall sense agency, but it can. If the text constantly betrays the expectations of the reader, and if the presented choices do not give one a way of driving the story in a specific direction, then the experience can become frustrating. When used sparingly, however, plot twists on the other side of the link can make the story more exciting and can increase the sense of realism, because in life, too, good moves don’t always pay off.

In organizing a gamebook, authors and editors also tend to place narratively connected sections at some physical distance from one another. If the target section is placed next to the originating section, for example, one may accidentally see spoilers that will affect the decision. Suppose that in section 12 I can go to 13 or 280, and I happen to see, just see, that section 13 leads to death. How likely am I then to choose that path?

Typically, links are presented in groups of two or more, and they allow the reader to choose what to attempt next. Links that do not involve choices can be part of a gamebook too, like when a section ends with a single indication such as “Turn to page 77”. This kind of link can still present several advantages. It can break up otherwise long blocks of text, making the work less threatening for young readers. It can also provide exciting cliffhangers by interrupting the flow of reading at suspenseful times, becoming a pacing device.

A menu of links can also offer multiple paths of progression without giving the reader a choice. This occurs with random links, such as in “Roll a die; on a 1 to 3, go to 122; 4 to 6, go to 350”. Many gamebooks make a moderate use of this mechanism, reproducing in the process the unpredictable nature of reality. A small number of gamebooks use only random links for navigation, generating a different location to explore every time.

Another type of choiceless link is the status check, which redirects the story deterministically based on the effect of past events. Simple examples include “If you own a bronze key”, or “If you have 10 Life Points or more”.

Random links and status checks can also be combined into skill checks. In this case, the reader must produce a random result and merge it with a stat, as in “Roll a die, and add the result to your Stealth value. If the result is 8 or less go to 239; if 9 or more, go to 101”. Differently from purely random links, status checks and skill checks are influenced by choices previously made by the reader. If they don’t offer a choice now, they give long-term value to early decisions and strengthen the overall sense of continuity and causality.

Gamebooks being physical, self-contained objects, every link must be described in some way in the text. In most cases, as we saw, the links are listed at the end of the sections that allow progression. A variant is to present them inside a map and to allow the reader to “travel” around by choosing where to go next. J. H. Brennan did it early on with the map of the Stonemarten Village printed in The Den of Dragons (1984), which shows buildings with different numerical indications on them. To reach a certain building, the reader turns to the corresponding section, resolves the resulting interactions, and is then sent back to the map to choose where to go next. Michael J. Ward also relies on freely navigable maps in his DestinyQuest gamebooks, while marking each location in terms of difficulty. This way, the reader can choose to face some easier challenges first and leave the harder ones for when the character has been properly leveled up.

Problems may emerge, in a gamebook, precisely from the explicit nature of the links. Suppose you are reading Lair of the Lich (1985) by Bruce Algozin and you are leading your hero in the exploration of a treacherous dungeon. At some point you find an intersection that, among other options, allows you to go to page 111. You decide to take a different route. When later you encounter an intersection branching toward 111, you instantaneously gain the knowledge that that passage leads to the same location as the one you avoided earlier, even though the hero travelled neither! Moreover (spoiler alert), if you do travel to page 111 of Lair of the Lich, your hero falls in an ambush and perishes. This knowledge will certainly affect the replay value of the gamebook, making it less unlikely that anyone will choose to walk down that path again.

A common solution is to place some textual distance between instances of the same numerical indication. If there are at several or many sections in between two links leading to the same location, the reader is less likely to notice. This method can be enhanced if the chosen number is somewhat graphically unremarkable. Similar numbers can also be concentrated in specific areas on purpose, to prevent the reader from exploiting the explicit nature of the links. Was the section in which you died the 312, 213, or 321? Algozin’s choice of page 111 for a deadly ending is therefore particularly unfortunate, because 111 is «a rather curious number», as Tolkien put it, and is not easily mistaken for another.

It is also possible to disguise a connection to a known place by adding a section whose only purpose is to redirect to a specific passage. Suppose that in Lair of the Lich I already died by going to 111, so during my second attempt I am being very careful to avoid 111. Then (fictional example) I meet an intersection that shows 65 and 198. I confidently choose 198, and when I turn to that page the text simply says: «Go to 111». It is a jerk move, but it is technically fair, and it has been done.

Most links in gamebooks are clearly visible and understandable, like in the examples above, but other forms of presentation are possible. As long as a gamebook shows all its links somewhere, authors can displace and disguise their links in any way they please.

Examples are in the series Cretan Chronicles (1985-1986) and Hellas Heroes (2018-2022, heavily inspired by the former). Both series are set in the ancient Greece of myth and explain that in some sections the protagonist may have a premonition. When the number labeling a section is printed in italics (41 instead of 41), the reader can choose to “take a hint” by jumping 20 sections ahead (in this case, to 61) to discover the effect of that intuition. By making some links less obvious, this device also captures some of the awe of a world in which the gods communicate with humans in mysterious and ominous ways.

Similarly, the instructions to operate a link may be contained in a different section from the one where the link is found. I call this device a “split link” because the information needed to activate the link is divided between at least two sections. This type of link has always been a staple of the Fighting Fantasy series and is still popular in modern gamebooks for adults. In Starship Traveller (Steve Jackson, 1983), for example, the protagonist must find the time and coordinates of a black hole, and then combine them in a specific way. Each coordinate is a number found in a different location of the book, and the instructions on how to use them are in another section still. Only by finding all three sections and following the instructions, can the reader reconstruct the needed section number and therefore activate the link.

A link of this kind may be not just split, but also secret. Unsurprisingly, a secret textual link is often employed to represent a secret passage. In Steve Jackson’s House of Hell (1984), the reader may learn that there is a concealed door under the cellar stairs, and that that passage is activated by subtracting 10 from the section number where the stairs are mentioned. This split link can be described as secret because a reader reaching the stairs without knowing about the passage would have no way of realizing that the section contains an unstated link.

A variant of the split link is the delayed link. A delayed link instructs the reader to make a note of a codeword and a section number, like Antidote 218 or Willana 512 (from Graham Wilson’s Bruidd, 2020). Later, the text may direct the reader to the indicated section, as in “if you have the antidote, turn to the number associated with it”. In a sense this is a split link, because to follow the narrative the reader should combine pieces of information from two different sections (the one with the code, and the one authorizing its use). In practice, the link is already operational the moment it is presented, and a reader can choose to follow it and jump ahead in the story in a way that is not possible with a proper split link.

Finally, a link may offer its information in the form of a visual, spatial, numerical, or verbal puzzle. Chris Matthews’ The Dregg Disaster (2022), for example, asks its readers to solve algebra problems to find the path to move to next. Steve Jackson’s Creature of Havoc (1986) includes a sequence of apparent gibberish, which, when deciphered, contains a navigable link:

‘Ypvruprpg rfss ehbs ab ffne wbtchf def pvlucdbtv r fep fodf str vctj pn. Spo lbray pv uhbvfe dpn fe wfll ethp vgh uypv uk np won pt ow hyo prow hbt. Bvtay pvo hbvfi cbv sfdatw pipf ath favbp pwse tpebf ulpst. Zhbr rbd bnam brrah jrns fl f ehbsa dfc rffdey pvr udfst jny. Yp vushbl lar fmb jn ijni hjsi dvng fpnso b nd adp omy objd djng Fp rojibma db rrbm pvs suypv rumbs tfr.’ Jfiy pvuc bna vn dfrs tbn dahj mi tv mut p orff frln cf enj nfty. ‘Y pvru fjrs ti prd ftejsi th js. Rf pprtoh rodvt yubta thfe yfl lpwstp nfemj nfs. Llb vlenpw ob ndahfbdath f rfejm mfdjb tfly. Jiwjllibf ewbt chj ng.’ (369)

Virtually any kind of puzzle can be included in a gamebook link, as long as the solution, once found, points directly to the label of one of the sections.

The Loop

The loop is a link that brings the reader back to a section that was (or could have been) visited previously. Sometimes, such a link simply leads to a place that can be reached multiple times. If the section features no encounters (like it is common in mazes), the reader can use the loop to go through the same location any number of times without any logical problem. If the location includes significant events, though, a status check is needed to keep the continuity straight, as in “if this is the first time you visit this section / otherwise”.

In some cases, the loop can create a surreal time-traveling effect. Packard says it plainly in Underground Kingdom (1983) before a link that brings the reader back to the previous choice: «You feel that you have been put into a trance. Stranger still, you sense that something has set time back – that you are being given another chance!». In other cases, loops can connect distant sections of the text. R. A. Montgomery’s The Race Forever (1983), for example, depicts two car races that the reader can participate in: a speed race and a rough road race. Whichever one is chosen, completing a race leads back to the beginning of the other race, which in turn will lead to the beginning of the other race, and so on. The general structure of the book is reminiscent of the infinity symbol ∞, with two main paths looping back to the beginning of the other.

Packard’s You Are a Shark (1985) even gives its system of loops special meaning and significance, employing it as a symbol for the Buddhist concept of samsara (the endless circle of life, death, rebirth). The protagonist offended a deity inhabiting a Nepalese temple, and as a punishment their consciousness is shifted into the body of several animals. Early on, we are told that «time may seem to go in circles» (10), and the branching structure indeed traps the reader inside a textual maze that seems inescapable. The goal is to find a way out of the endless recursiveness, and the structure of the book mirrors that message perfectly.

Not all textual loops are this hopeful, though. The sadistically designed Creature of Havoc (1986), for example, can trap the reader inside a fatal cycle of battle. If you reach section #39, you enter combat with a Chaos Warrior. If you survive this fight, you must turn to #397, and fight yet another Chaos Warrior. If you win this time too, you must turn to #46, where you are attacked by a new Chaos Warrior. If you win, you must turn to #39 again, and face the same (or is it another?) string of Chaos Warriors, and so on, endlessly. Once you hit section #39, there is simply no way out. Sometimes, a loop may just be a gradual and cruel way to tell the reader that they lost.

Structure

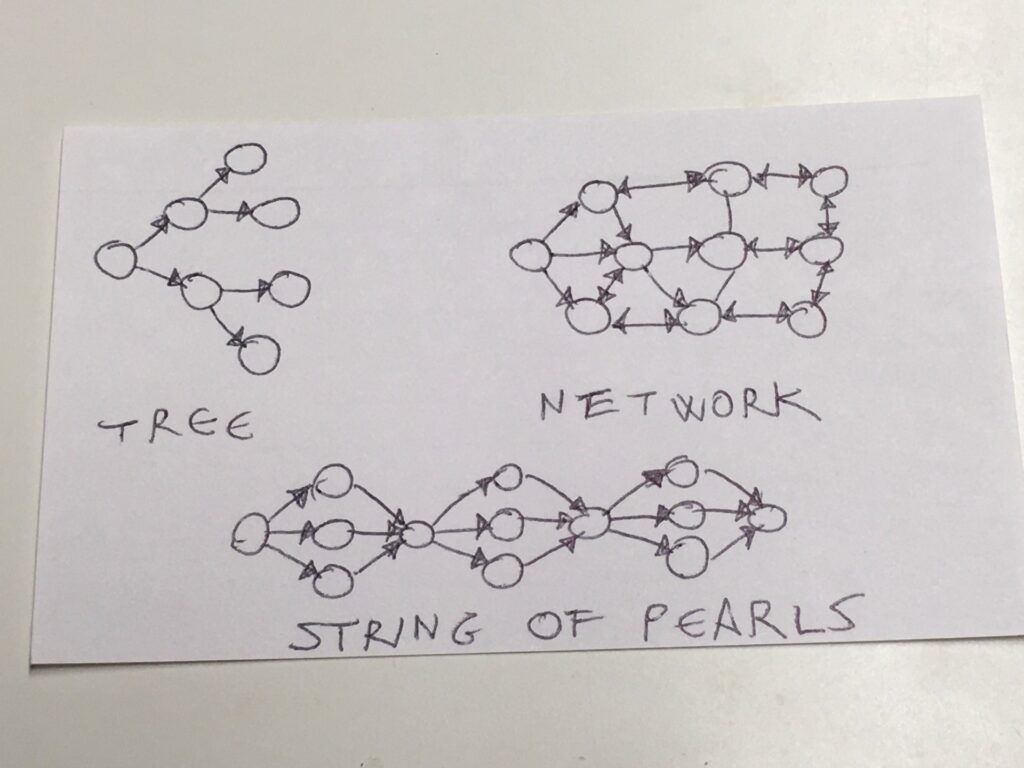

The way the links connect the textual sections can take on an infinite number of forms. In practice, though, most systems of links in gamebooks can be divided into three broad groups: the tree, the network, and the string of pearls. These structures take their name from the shape of the flowcharts in which they can be visualized. They are not the only existing configurations, but they are by far the most common. I make use of these categories with full awareness that individual gamebooks may belong to a type only to degree. Plenty of works don’t fall neatly within one of these groups, but almost every gamebook I ever examined resembles one of these types or hybridizes between two or all three, which is why I find this categorization useful.

A branching structure commonly found in gamebooks is the tree. The term is intuitive, and it indicates a gamebook in which most sections have only one link leading to them. When that is the case, a map of the book’s structure will tend to resemble a tree, with narrative paths diverging in multiple directions. This is the structure of the first known gamebook (Consider the Consequences), and its popularity skyrocketed starting in 1979 thanks to the Choose Your Own Adventure series, which adopted it with unflinching regularity.

As an organizing principle, the tree presents the advantage of being very simple to navigate. For the author, the tree makes it easier to preserve continuity and avoid illogical connections, because different plots don’t usually converge or overlap. As the branches mostly diverge from one another, great thematic variety can be included too. Each reading path, from the beginning to an ending, will also cover only a small portion of the book. If the structure branches in symmetrical ways, for example, the path emerging from first choice will lock away half of the entire book; the second choice will remove another quarter from that path, and so on. The tree therefore tends to offer strong incentives to reread the text and explore new paths. The experience will also have a strong temporal feeling because each narrative path is strictly organized as one event after the previous.

Due to its divergent nature, the arboreal structure works very well in stories whose main intent is to present a large variety of situations. It works less well in goal-oriented gamebooks, especially if the author wants to challenge the reader to find a single happy ending. If the narrative paths keep diverging, a single wrong choice means to be locked out of any chance of victory for that session.

A different kind of structure is the network, in which many sections can be accessed from multiple other sections through loops and convergences. A flowchart describing this kind of structure looks more like a map than a tree, as many of its narrative paths can be navigated with considerable freedom and accessed and left in multiple ways. Networked gamebooks tend to have a strong spatial feel, because, like space, we can travel them in many combinations of directions. They are the most natural format to represent mazes, complex locations, and any kind of scenario in which «navigation of space (both of the storyworld and the material book) is the object of the game» . For the same reason, they engender a strong sense of freedom and agency, allowing the reader not just to choose where to go next, but also in which order and how many times to visit certain places.

The popular Fighting Fantasy series and the much less successful The Legends of Skyfall series (four volumes by David Tant in 1985) made large use of networks to create citadels, castles, mansions, swamps, forests, mines, pyramids, and a myriad of other labyrinthine and treacherous places. Very often, the spatial organization of the books was emphasized by using the name of the main location as the title (The Forest of Doom, City of Thieves, House of Hell, Garden of Madness, Mine of Torments). Later, the series Fabled Lands (from the 1990s), Steam Highwayman (from 2017), and Legendary Kingdoms (from 2019) extended the idea of a networked gamebook to create open worlds that can be explored with immense freedom and do not rely on a single mission to complete. The principle applies not just to each volume but to the entire series, which the reader can navigate freely from book to book. Effectively, each book becomes an open region in a sprawling fictional world.

While the advantages in terms of immersion are obvious, a network can be difficult to manage at the level of the design. A networked gamebook must ensure that the story makes sense across each and every reading path, and that each section is logically connected to all sections leading to it. If the text allows readers to backtrack and return to previous locations, then vanquished enemies must stay dead, looted chests should stay empty, and so on.

The third type of common structure combines the robustness of the arboreal structure with some of the freedom to roam of the network. It is the structure at the core of series that are praised precisely for their balance between story and playability, such as Lone Wolf and The Way of the Tiger. This type of organization doesn’t have an agreed-on name, and I choose to call it “string of pearls”. This is an image that, consistently with the previous cases, captures a textual configuration in a visual metaphor.

A string of pearls allows the reader to maneuver within local networks or trees only to merge all possible paths into a single mandatory section. From there, the narrative branches out again in multiple directions before merging into another bottleneck, and so on. In the metaphor of the string of pearls, the networks and trees that allow freedom of navigation are the pearls, and the bottlenecks are the points where the pearls touch. The narrative advantage is that these bottlenecks, which are mandatory and always encountered in the same order, can construct story arches as solid and satisfying as those of linear fiction. Within this framework, though, the reader can craft different stories, experience many encounters, and make better or worse decisions. Such textual organization offers enough structure to function as a clear narrative and enough choice to be enjoyed as a game.

Speaking of games, most strings of pearls are meaningful only if game mechanics are employed. The presence of a bottleneck may otherwise give the impression that all choices leading up to that point are irrelevant. For sure, the text of the bottleneck may have different implications depending on the path that was taken to reach it, but this possibility may not make a significant difference in the reader’s experience. With game mechanics, though, a gamebook can include long-lasting effects that can be carried into and through a bottleneck even if they are not explicitly described in the text.

For example, in Joe Dever’s Fire on the Water (1984, second book in the Lone Wolf saga), the reader can explore a cluster of eleven sections before reaching the first bottleneck (at #300), and then a cluster of twenty more before reaching the second bottleneck (at #240). Without game mechanics, the path on which one reaches #300 and #240 would be of little or no import. The structure of the book, however, leads the hero to face a minimum of one battle and a maximum of three before reaching #240. While the text of section #240 never changes, a varying number of battles and different random elements in each battle may cause the hero to be in very different conditions by then, from unscathed to barely alive. Game stats and mechanics can create unique narrative situations around textually immutably bottlenecks, giving real meaning to the choices that brought the reader to that point.

Consistency

The gamebook is not an abstract form and ultimately the texts contained in the sections, connected by links, and organized as a structure, will come together to form a fictional storyworld. Due to the branching nature of the gamebook, the storyworld does not have to be internally consistent, and the resulting inconsistency can be an expressive choice. For this reason, I use the terms “consistent” and “inconsistent” in a purely descriptive and neutral way.

In the consistent approach, the author creates an internally robust storyworld and allows the reader to attempt different courses of action without altering the fabric of the setting. This approach does not require much explanation, because many people have experienced it in forms of interactive fiction such as role-playing and video games. If you approach the boss from the right or from the left, it is usually the same boss.

The consistent approach is the most common in gamebooks from the origin of the form to the present. It appears that in most cases readers like to solve problems and strategize, which can only occur if the storyworld abides to its own rules. The consistent approach is most commonly taken in gamebooks that include game mechanics. If I am going to choose when to use a certain item or skill, I usually want to be rewarded for doing it well, which can’t occur if major elements of the story flicker in and out of existence without explanation.

A remarkable exception is in the game-based Shadow over Nordmaar by Dezra Despain (1988). The protagonist is an amnesiac hero who, at the end, will be revealed to be one of two people. In the initial sequence, the hero must decide the direction of travel, and that decision determines who the character in that scene already was. The inconsistent approach comes from the realization that each branch of the story must only be consistent with itself, with no obligation that the branches be consistent with one another. This is evidenced by the fact that the statements «Character A walked north» and «Character B traveled west» are perfectly logical. It is only when these plotlines are compared after multiple readings that the inconsistency emerges.

A. Montgomery, who co-created the Choose Your Own Adventure series, specialized in designing gamebooks around this kind of inconsistencies, achieving highly surreal results. In his House of Danger (1982), the contents of the titular mansion change depending on the timing of entrance, direction of movement, and whether one goes in solo or with friends. None of these factors should impact what was already in the house. Yet, depending on those choices, the contents may involve intelligent chimps on flying machines, aliens planning to package humans as meat, a benign organization for peace and societal development, the ghost of a man asking for forgiveness, or a different version of the same ghost who now transforms the visitors into infants or decrepit people. It can be extremely entertaining to lose oneself in such a bizarre narrative funhouse, but it requires a state of receptive acceptance and a deep sense of wonder. Probably this is the reason why inconsistent gamebooks have tended to target younger audiences. Only occasionally have inconsistent structures had a role in gamebooks for adults, with an example in Death by Halloween (2013) by David Warkentin. In inconsistent gamebooks, what is lost in terms of strategy and agency is made up for by the pleasure of watching parallel worlds pop into existence and then change, shift, and morph into supremely free narratives. It is storytelling unconstrained by any logic, and akin to the mystery of dreams.

Conclusion

This essay was designed to equip the reader with a conceptual map, a vocabulary, and a set of critical tools for what I hope will be a trend of scholarly studies on the gamebook. The form today has a presence that may be quantitatively smaller than the original wave, but that is significant in terms of creative freedom and inventiveness. In this landscape, many exciting gamebooks from the 2010s and 2020s are waiting to be examined from a scholarly perspective, and many more will join their ranks in the future. I hope that this contribution will offer some clarity and a useful starting point to future scholarly endeavors.

At the same time, I took great care to avoid creating a false dichotomy between “trivial” gamebooks for kids of the 1980s-1990s and “artistic” adult gamebooks of the recent past and present. If anything, one of my goals was to showcase the exquisite, unapologetic strangeness achieved by some early gamebooks. Montgomery’s House of Danger and Packard’s Inside UFO 54-40 may be some of the most experimental literary experiences that a child could have at that time, and maybe even today. And what a shiver of metaphysical dread is in Packard’s You Are a Shark, especially in the storyline in which you, a shark, devour the squid that you were in another storyline! As Jamieson put it, «are… are you eating yourself? Yes, you’re almost certainly eating yourself. That’s some serious multiverse-level mind-screwing for a book aimed at 10-year-olds». There was intense experimentalism in early gamebooks too, and it was made all the most impactful by its being nested inside apparently harmless fiction for children.

Moreover, all fundamental key devices of today’s sophisticated gamebooks, from the split link, the secret link, the locked room, the puzzle link, or the “premonition link” of Hellas Heroes, have their precedents in the juvenile texts of the first generation. Modern writers of gamebooks for adults may construct different experiences around those building blocks, but the blocks themselves remain largely unchanged. The difference is a matter of degree rather than a quantum leap.

Early media studies of digital fiction, as I mentioned at the beginning, inflated the importance of their own subject by overlooking and minimizing important parallels and possible sources. As scholarship on analog gaming continues to expand and may finally come to investigate the gamebook, my hope is that we will not walk a similar path. A bifocal approach that appreciates the creativity of the 1980s and 1990s and places recent gamebooks against that rich background may end up being the most fruitful and accurate approach. But ultimately, the choice is yours.

—

Featured Image is “You’re the Star of the Story.” Image by Derek Bruff on Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

—

Marco Arnaudo is a Professor at Indiana University, Bloomington, where he teaches about games, comics, military studies, and Italian culture. He is the author of several books, including Storytelling in the Modern Board game (McFarland, 2018). He designed several tabletop games. His most recent game is Four against the Great Old Ones (Ganesha Games, 2020). He reviews board games on his YouTube channel MarcoOmnigamer, which has 25,000+ subscribers. Other interests of his include martial arts, carnivorous plants, and jigsaw puzzles.