Content warning: Trauma, precarity,

self harm, climate change anxiety.

Introduction: Solo Journaling Games as Critical Intervention

The game tells me I probably will not survive, and I do not the first time I play. Instead, I go insane, destroy all the equipment I need to stay alive, and die a horrible and unrecorded death, alone and afraid, drowned, suffocated, and crushed to death in my tiny bathysphere hundreds of meters out of reach of sunlight.

In this article, I detail key experiences in my playthroughs of two solo journaling games that engage explicitly with environmental themes and use them to model material interventions into queer theory. In the first game, The Crushing Dark: A Solo Journaling RPG (2021), I explore the fragility of subjecthood by documenting my player character’s (PC) attempts to maintain the integrity of a bathysphere against an inhospitable, albeit beautiful, submarine world. In the second game, Dwelling: A Solo Game for Ghosts (2021), I investigate the erotic possibilities of memory as a ghost floating through rooms, creating memories, and making marks. A solo journaling game is, more or less, what it sounds like: a one-player game a person plays by recording events in a journal of some sort. But even these two seemingly basic features are slippery to pin down when considering the many forms they can take. The recorded events can be real, fictitious, or somewhere in between, and the journal itself can take a myriad of different forms from written entries to marks on the skin. Moreover, the very mechanic of producing a personal journal for a fictional character highlights the tenuous slippages between the player and the player character. These slippages are not unique to solo journaling games. Terminology like “bleed” already exists to describe situations when the feelings of a player and the feelings of their character influence one another. These concepts, however, are typically treated as conditions that can arise from play and not the foundational mechanic by which gameplay happens in the first place. Finally, as these journals are personal, they are always selective. By producing inherently incomplete records of gameplay, solo journaling games always linger unresolved past their own completion. This unreliable physical evidence of play, at once a faithful record and a fabricated story, unsettles the presumed stability of the arbitrary stopping point we colloquially call ending a game, in which a game neatly stops and its player neatly disengages after they are done playing.

The slippages these games’ journaling mechanics hold in focus closely mirrors a slippage often missed in queer theory, especially high queer theory that derives abstract concepts from queer subjects without centering the material limitations of those subjects’ lived realities. Yet, as the world becomes increasingly precarious for queer people, it becomes more important than ever to be critical of what the material possibilities of queer thought creates for queer thinkers. One place we might begin to think through those possibilities is by considering the accidental vulnerabilities possible in mediated interactions with objects of study and play. To do so, I supplement queer theorizations with the environmental humanities concepts that actualize the material limitations of queer bodies existing in the world: precarity and porousness. Precarity is the likelihood of a subject to lose a position they hold in the world, like a house being swept away in a flood, and porousness is the exchange of fluids between the inside and outside of a subject, like breathing toxins in and out. I begin with a brief overview of queer subjectivity or how queer theory imagines queer subjects in order to situate my critical interventions and then provide a close reading of each game, highlighting how the experiences that emerged from play offered concrete perspectives on more theoretical inquiries.

As a final note, when I say “material” or “physical,” what I do not mean is “more real” or “more authentic.” Reality is different from materiality, and any claim to authenticity is inherently an imposition of arbitrary political stakes onto something else. Claims to either realism or authenticity are not interventions I am interested in making here. In my case, neither of the characters nor the situations I role-played in The Crushing Dark or Dwelling were realistic for me. Instead, I am interested in how, through the act of journaling fictional events, I engaged in personal acts, recalled memories, reflected, and otherwise had genuinely meaningful experiences. While the situations were fabricated by the game, the experiences of joy, fear, frustration, and epiphany were all my own. I found both games to be insightful but imperfect, critically engaging but occasionally challenging to engage with. There were aspects of these games that I enjoyed, but there were just as many that were confusing, boring, or downright unpleasant. Therefore, in discussing my own resonances with these games, I also seek to embrace the ways these games did not resonate with me. In doing so, I follow scholars like Jean Ketterling in remaining “purposefully ambivalent,” seeking to resist the urge to situate my observations and experiences with these games into overarching frameworks of power and authority and instead explore what might come from allowing potential ambiguities and inconsistencies to persist unresolved.

Critical Materials and Critical Environments

Queer identities and imaginations may be fluid, embracing volatility and flowing easily from one state to another, but queer people are much less so. It is painful, dangerous, and exhausting to evade capture by normative systems of identification, and it is painful, dangerous, and exhausting to iterate beyond hegemonic cultural imagination. For example, Eve Sedgwick’s Touching Feeling focuses on the intimacy and vulnerability that comes from engaging with objects that resist static form and stable understanding, as well as on the capacity of affective relations to reshape our understandings of the world. Yet, while works like Sedgwick’s are vital in teaching us the analytic value of disorientation and exploring the implicit ambiguity in our identities, cultures, and institutions, they do not offer practical solutions for considering the concrete, material expressions of these interventions.

By centering the ever-shifting material environment in which queer subjects sit, however, we can better consider these lived conditions. For example, thinking about atmosphere as opposed to metaphysical space draws attention away from a subject’s fluid exchange with concepts and toward more concrete considerations of a body’s vulnerability. What this framework makes more immediately legible is that the conceptualizations of fluid identity queer theory explores are always as much avenues for danger and violence as they are for joy and fulfillment. In other words, what sustains us might also imperil us. As Jean-Thomas Tremblay argues in Breathing Aesthetics, the very act of breathing, one of the most central and essential life functions is “inevitably morbid…As long as we breathe, and as long as we’re porous, we cannot fully shield ourselves from airborne toxins and toxicants as well as other ambient threats.”

Therefore, while theorists rightfully laud the excessive potential of queerness in imagining radical alternate subjects, we would also do well to consider the effects these theorizations have on actual people. Trans scholars like Hil Malatino, for instance, remind us of the rage, burnout, and other “bad feelings” that accumulate in people when performing the work of resisting oppressive, hegemonic systems. A critical place to engage with these effects and affects is through games, play, and media studies that have taken up these bad feelings as generative sites of inquiry. Bo Ruberg argues through the provocation of “no fun,” that we should “explore alternate ways of feeling, desiring and being” and “[disrupt] dominant and implicitly heteronormative presumptions about the affective purpose of [games].” Similarly, Ela Przybylo’s “asexual erotics” concurs with Ruberg’s goal of pushing us to resist politics of capitalist consumer culture’s rampant expenditure and endless disposability. Przybylo cautions, however, that in order to do so, we must consider both ways of being that are “potentially excessive of capitalistic white structures, identity categories, and contemporary modes of being together” and disavow “celebratory rhetoric in relation to identity formation, and [attune] to the darker modes of queerness.” Through journaling in The Crushing Dark and Dwelling, I blurred the boundaries between many kinds of subjecthood—player, player character, genuine memories, fabricated memories—but had to put in effort to do so managing difficult emotions, performing physical tasks, allocating time and resources. Critically centering an act like journaling, therefore, helps to navigate queer subjecthood without losing sight of the concrete precarity of being a queer person living in the world. In doing so, critically playing these games offers the generative value of imagining ways to disrupt hegemonic ideologies about identity and subjectivity, while also considering the accrued exhaustion that comes with these iterative efforts.

Games, particularly analog games that require players to physically act out gameplay mechanics, help to generate uniquely rich spaces to explore these critical interventions. For The Crushing Dark and Dwelling, the framework of precarity and porousness is relevant, not only because each game’s content engages with environmental themes, but also because of solo games’ unique position within the tabletop world. Solo games are economic products; as such, they participate in systems of resource extraction, environmental devastation, and colonialist distribution and yet tend to exist at the margins rather than at the center of large-scale, highly profitable, highly reproducible analog game markets. They are often independently produced and decentralized in terms of distribution, manufacturing, and design, especially when compared to a highly-profitable franchise like Dungeons & Dragons.

Critically playing games like The Crushing Dark and Dwelling offers alternative modalities and relationships of queerness, queer identity, and queer play. This practice allows for more nuanced and emergent possibilities to understand the critical value of queer, affect, environmental, play, and game studies as well as to consider the complex relationships that arise when these disciplines are put in conversation with each other rather than treated as separate, unrelated fields. Therefore, I draw on the work of Max Liboiron, who understands humans and environments as co-consitutive and in relation to one another rather than understand environments simply as inert, passive things to be damaged by humans. These ludic, queer, and environmental relationships are always slippery, pervasive, and unruly, oscillating between abstractness and materiality but never settling in either position.

Precarity and Subjecthood in The Crushing Dark

After I die, the game invites me to consider how my journal might be found and I decide it won’t be. How could it? If I could not survive, how would a flimsy few pieces of paper succeed where I could not?

I sit in the dark, contemplating these questions until I remember an assignment due tomorrow and turn the lights in my living room back on. Even as I begin working, a moment from the game lingers in my mind: there was a moment, you see, where I could have cheated, where I realized that the pile of stone representing my lifeline was going to fall over. Instinctively, I grabbed for them, began to stabilize them. I considered holding them like that another round or deconstructing the tower and playing on as though it were still standing. No one would have to know—it was just me, alone in the dark about to die and realizing I didn’t want to die this way. Gently, I let go and let the tower fall.

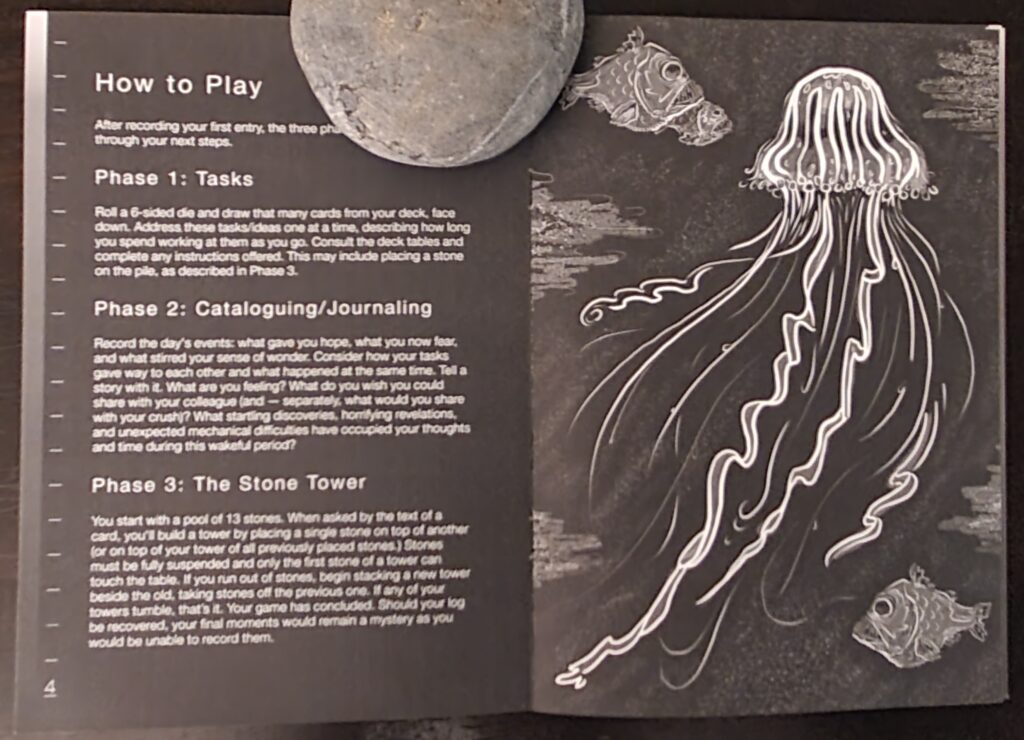

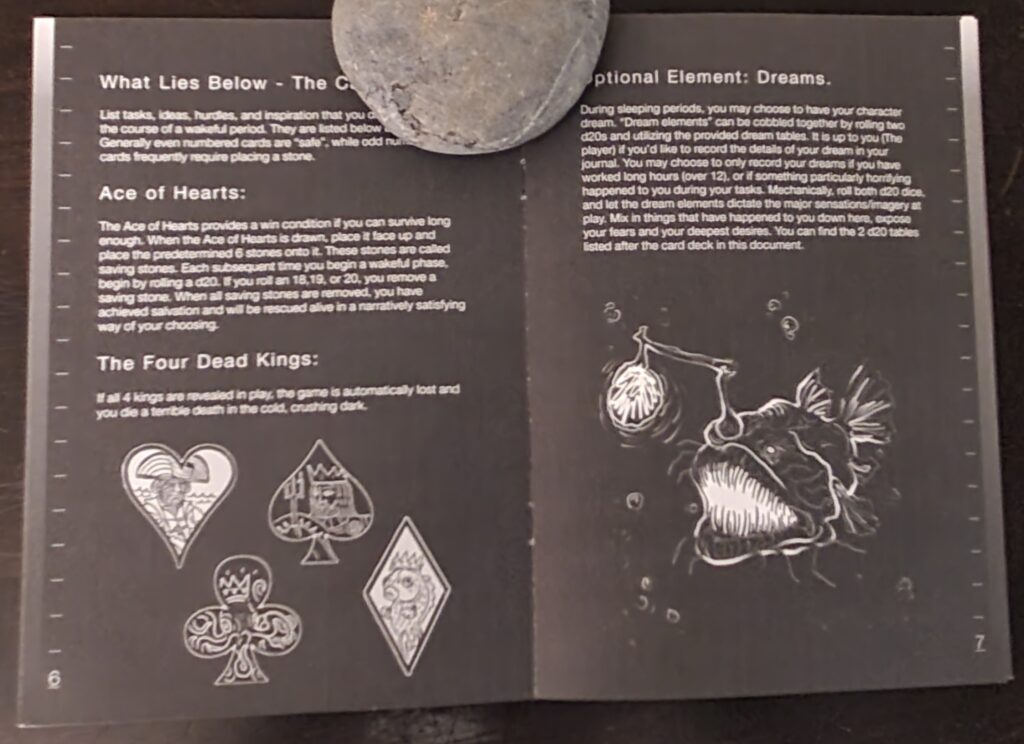

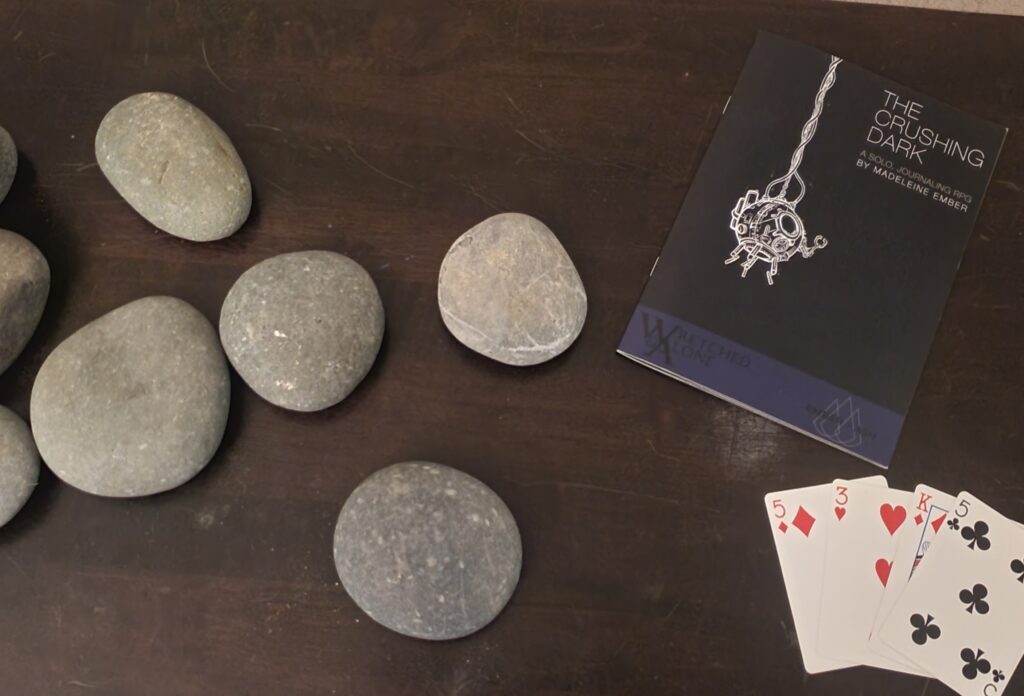

The Crushing Dark is a game about decisiveness and indecision, about stability and precarity, about death and survival. It is a game about dying alone and afraid and a game about realizing that you do not want to die alone and afraid. In it, a player takes on the role of a brilliant but overzealous 1950s scientist descending into the depths of the west Pacific Ocean in a small bathysphere of their own experimental design. To play, the player uses a deck of cards and several dice to determine the events of each day. The player interprets and records these events at the end of day (provided they survive) in a series of journal entries addressed to a fellow scientist and hopeless crush somewhere above the surface. The player also starts with a pile of stones of their own choosing which represent the integrity of the bathysphere. I mean this statement literally: the game actually instructs the player to go out and gather stones before they begin playing. Whenever something bad happens, the player stacks these one on top of the other, and since the player has picked the stones, if the pile is difficult to balance (as it was for me) they have their own material selection to blame. If the pile falls over at any point, the vessel fails, the player character is killed, and the game ends immediately.

The potential events range from good to bad to distressing to catastrophic. In my particular playthrough, I experienced imposter syndrome, saw ethereal deep-sea creatures, fixed a hot cocoa machine, and sabotaged my adventuring vessel in a fit of temporary insanity. These events within the player’s bathysphere highlight the main source of both engagement and horror in the game: the fragility of their position. As long as the game is in session, the PC is alive, but their survival is always wholly dependent upon the maintenance of a thin, increasingly precarious layer of metal. From a practical standpoint, everything is fine at any given moment. Everything also has the potential to very rapidly become not fine, but if the player does nothing, they can assume they are safe because neither water nor ocean life can get into the bathysphere. The horror arrives, however, in the realization that none of the game’s mechanics allow the player to do nothing. The momentum of gameplay keeps the player descending further and further into the ocean and away from any kind of permanent safety. Each card drawn, each die rolled, each stone stacked increases the likelihood that something will go unsalvageably wrong and the player character will suffer a horrible end. Everything hangs not so much in balance, but in tension, quite literally between life and death. Everything that happens mechanically in The Crushing Dark, therefore, is reducible to playful mediation of the tension remaining alive in a precarious environment. Every event, from every scientific observation to every breath is directly mediated by the thin metal walls of the vessel the PC descends within. When I played this game, whatever happened, my ultimate question was always reducible to “how does this affect the integrity of my vessel?”—if the vessel is lost, so am I.

Yet, the more uncertain my survival seemed, the more sure I became about the emotional and physical state of my character and what they would do at any given moment. As my character’s safety measures began to erode, as their mental fortitude began to deteriorate, I began to reinforce them, supplementing the failing bathysphere with my own feelings, my own fears and doubts, my own hopes and triumphs. In other words the more precarious my character’s situation became, the more certain I became of who this character was, what they wanted, and how they would act. Yet, the more certain I became of who this character was, the less clearly I was able to differentiate between that character and myself. When I realized my character was going to die, I knew they didn’t want to die because in that moment, I did not want to die either.

In having the player pick their own stones, the game draws attention to craft as a prerequisite for adventure. Rather than simply tell them that they have built the bathysphere they spend the game inside, The Crushing Dark, has its players roleplay precarity by drawing attention to the process of craft. The transparency of process here serves two main functions. First, at the level of practical game design, it is a way of engaging the player. By starting the game in an unstable device of one’s own creation, the game opens the door for play with hubris and guilt. When something inevitably goes wrong with the device, the PC might have any one of a myriad of emotional reactions to that event. More investment simply makes for a more engaging play session.

More relevant to this piece, however, is that the player explores the entangled involvement of journaling, not through a personal diary but through an official scientific data log. Personal involvement is often elided out the presentation of real world scientific studies, and critics of queer theorizations often deploy cold, hard data in order to undermine it with supposedly more objective and foundational forms of knowledge. However, as Mikhaila Friske et al. argue in their work linking datafication to artistic craft, data is not an event but a process. It does not leap forth fully-formed; instead, “materials, data, and humans collaborate to produce physical data representations.” When I played The Crushing Dark, I could easily imagine my character pacing about a busy lab muttering into a tape recorder or scribbling observations and calculations into a notebook. Indeed, many of my entries, even the most personal ones, included some measure of scientific engagement, whether a key observation or simply a commitment to record keeping. In envisioning my journal as a data log as much as a personal account, I learned to roleplay what Friske et al. call “contrasting the experience of the data with data of the experience.” I could not parse a singular dominant narrative from my data; instead, narrative emerged organically as I wrote entries entries piece by painful piece.

The fact that the events of the game take place in an inverted fish tank is not lost on me. I see crafting as a link between Friske et al.’s interventions into data narrative and Samantha Muka’s provocations in Oceans Under Glass. In that book, Muka tells the story of tank craft by framing it through a lens of hobbycraft. The aquariums so pivotal in the serious study of such fields as marine biology are completely dependent upon the intimate passion projects of hobbyists. Aquarium enclosures draw attention to the constructed artificiality of so many of our encounters with the ocean. Viewed through this lens, the bathysphere in The Crushing Dark operates as a multi-directional aquarium. Since the PC is contained within it, it draws our attention to the arbitrary centering of human actors in the field of science and in turn, the artificiality of their importance within it.

The transparency of craft and the mechanics of data entry draw attention to the messy process rather than the quantifiable event of data. Yet, we must still trouble the presentation of scientific inquiry in The Crushing Dark as hobbycraft and the presentation of the playable character as an agentive outsider. As Aaron Trammell details in The Privilege of Play, “the hobby,” the network of war games, role-playing games (RPGs), and board games, collectively “gatekeep minoritized people from participation.” Because of embedded networks of white privilege, those most likely to have the time, space, leisure, and disposable income needed to acquire and maintain a collection of miniatures at cis, heterosexual white men. The hobby is foundationally an expression of white supremacist logics, and The Crushing Dark is in no way immune to this history. Indeed the PC’s infatuation with a non-agentive non-player character in a one-sided courtship travels uncomfortably close to toxic masculinist cultural norms that seek to entitle men to sex with women rather than empower the agency of both parties.

We can, however, also excavate a concurrent reading by viewing the game through the lens of material and experiential data narrative: The Crushing Dark’s bathysphere certainly invites the player to roleplay the hubris of an individual determined to center themselves in a hostile environment to which they are not accustomed, but so too does it highlight the irresistible pull of an intimate immersion into an environment facilitated not by impersonal scientific calculation but passionate curiosity. I use “cold” here not to foreclose the possibility that a scientist might be driven to their work by passion but instead to draw attention to the overlying and wondrous subjectivity that always shapes the acquisition, analysis, and implementation of supposedly objective data. In doing so, it invites us to consider what possibilities might emerge from considering technologies of mediations as extending vulnerable entanglements rather than foreclosing the possibility of intimate slippages.

If I could voice only one qualm with the design of The Crushing Dark, it is that so much of the game is concerned with facilitating and fostering a claustrophobic sense of dread that it is easy to forget that the game pays just as much close attention to the strange and wonderful things the PC observes outside their windows. Typically, each section has an even split of prompts, half bolstering a sense of hope, half feeding a sense of dread. For instance, one prompt reads:

You enter a strata of the deep that is tinged a dull orange. The incredible number of lumens emitted by your not-yet-patented wet-sulphur torches seems to congeal and puddle about you, only six or eight feet beyond. You see dark, squirming shapes within the orange glow if you look too long.

For this particular prompt, nothing happens to measurably worsen the player’s situation. They are free to respond, record, or ignore the lights as they see fit without having to place a stone on the increasingly precarious pile in front of them. In giving the player something engaging though not quite explicitly hostile, the narrative of the game draws the player in closer, close enough to bite, certainly, but also close enough to caress, close enough for mutual, reciprocal recognition, that seductive negative space of infinite iteration that always draws in closer, always envelops further.

Porousness and Homemaking in Dwelling

When the game tells me to make a mark on my skin, I do it lightly with a fingertip. As I do so, my finger runs over the small, raised marks on my skin from when I opened my arm with a razor blade in my teenage years, now a subtle array of parallel lines running up my forearm. I can remember the pain and the pleasure of making these marks, but can no longer recall the exact moment of inscription the way I could a decade ago. As my finger glides up my arm, the marks crisscross for just a moment, one fading almost as soon as it is made, the other lingering long past its initial moment of inscription, past my memory of it, past, likely, my entire life.

Playing Dwelling was painful. It made me think of the fragility of my existence and of the enormity of the world and of the smallness of my place in it. It made my body feel unstable, permeable, malleable, diffusive, expansive. It made me want to hold onto things, to batten down the hatches, to keep myself safe against the world outside, to shut the door to myself and never open it again.

In Dwelling, a player plays an embodied, spectral spectator navigating a home that was once familiar but is no longer. The gameplay mechanics revolve around this figure seeking to recuperate fading memories by leaving impermanent marks alternately on the game itself and on their body. Through its gameplay, Dwelling troubles the idea that meaningful play is necessarily additive. In being a game that is as much about forgetting as it is about remembering, the game creates a critical play space in which memory itself operates as a mechanic for creating ephemeral and impermanent affective moments. The game explores these moments through its three key mechanics: summon, remember, and mark. In each case, something past manifests in the present, and the player must represent this event as a mark on their journal page, their body, or their mind. Through marking, Dwelling shows itself to be a game about lingering residue, but the game is also about turning the page, about watching marks on one’s body fade over time, and about forgetting the specifics of a moment of inscription.

I read this duality as an erotic exchange between the inside of a porous subject and the environment in which that subject sits. By erotics, I mean rooting my definition wholly in play—play between inside and outside, surface and depth, and self and other. Within the site of Dwelling’s home, this malleable and ever-changing space of erotic play, queerness enacts itself as a haunting, atmospheric hyper-presence that complicates both the radical denial of preservation implied by the act of forgetting and the perpetual iteration called upon by seeking to remember anyway. As a result, play sessions of Dwelling emerge as mediations on the expansive possibilities of erotic exchange between the inside of a porous subject and the subject’s environment. In mediating between extreme presence of a spectral ghost and individuated instances of specific memories, Dwelling actualizes the stakes of living in a world that is intolerant of certain kinds of life. By blurring the boundaries between what it means to haunt a place and to live in one, the game complicates cultural understandings of persistence and belonging, allowing its players to parse the ways in which one’s unique combination of precarious circumstances coalesces into this thing we call “home.”

We speak often of the restless or vengeful ghost, but we do not often consider the specter who simply remains in a place or the spectator who watches events but cannot meaningfully affect them. As Seb Pines writes in their artist statement for Dwelling,

Greetings to the “I” we both are in this story. I hope it wasn’t an uncomfortable shift, the I that is you becoming the I that is me. We can both haunt these pages as there is plenty of room for the two of us, and even the additional “you”’s that may return to it from time to time.

Environmental humanities is littered with analyses of objects that linger past their time resisting containment or removal. These analyses tend to focus on inorganic actors that do not belong because they do not arise without the intervention of human technologies: the irradiated area following a nuclear power plant meltdown or plastic contaminants in the pacific ocean. Rarely, however, do we apply this lens to things that live—to the endangered species or to the family in the flood zone that resists relocation. In seeking to decenter humans as the referential point in environmental studies, how might we use the embodied spectator in Dwelling to unlock potential analyses of actors, both human and non-human seeking to persist in a volatile and hostile environment? What is contained in the idea of a ghost that is non-malicious, that does not aim to frighten but simply to stay in a place that is already in the process of disappearing?

Dwelling reminds its players that in seeking homes, what we are desperate for is often not places but a fugitive feeling of belonging, the feeling that anything we hold dear might last. In pursuing that goal we often seek out not fixed locations but immanent flukes in the same systems that oppress us and create precarity. Take, for instance the shift from “homeless” to “unhoused.” In seeking to humanize people without permanent living arrangements, this term shifts focus away from the detrimental psychological damage being without a place one can call one’s home does to a person. The reduction of this issue to a building with four walls and a roof distracts from the trauma of feeling permanently out of place, like you don’t belong, and of being forced to wander through a world that systematically refuses even to see you. It is always holding your breath while you wait for the wind to be knocked out of you. It is this feeling of debilitating alienation that Dwelling lives in producing, maintaining, and re-enacting for its player, in drawing attention of the fragility of the place, belonging, and homestead. How do we hold onto things that are always decaying away around our ears?

Echoing Tremblay’s words above about breathing’s inherent capacity as a morbid practice, I posit that a dwelling is just as much a place to die as it is a place to live; it is just as much a place to fade away as it is to linger. If you have ever come home from a long day of work and taken a sigh, you will know that a home is a place in which we permit ourselves to expel the breath we must hold to preserve ourselves in the world outside, just as it is also a place where we refresh our breath to venture outside again. Similarly, Dwelling’s journal is a place where you teach yourself to forget, and, of course, a place to which you can return if, all of a sudden, you find yourself needing to remember. Dwelling’s setting of the house, therefore, operates as a kind of body which the atmosphere can permeate, once whose inhabitants have some but never total control over who and what is allowed to enter or leave. I notice the precarity of these arrangements everywhere, most imminently in the cocktail of compounded socio-cultural minoritizations that make up the ever-shifting legibility of my identity. The effect is that I feel frequently that I have overstayed in a place before I have even arrived—socially-speaking, I always haunt every dwelling I inhabit.

Conclusion

In this article, I have used environmental humanities interventions in order to interrogate the stakes of the solo journaling game genre within queer studies, affect studies, and game studies. Through close analysis of two examples of the solo journaling genre of games, I have sought to use considerations of precarity and porousness to materially ground queer studies’ more abstract theoretical interventions of subjecthood, while recognizing all the while that the ground we stand on is always already, figuratively and literally, constantly shifting. In navigating the messiness of these circumstances, we can use critical play methodologies to think through the practical labor of implementing queer imaginaries in our lived realities. However, as Liboiron demonstrates, “methodology is a way of being in the world and…ways of being are tied up in obligation.” Scholars like Rainforest Scully-Blaker and PB Berge urge us to remember that solo journaling games are, like all games, inseparably entangled within cisheteronomative power structures that precede our analyses of them. It goes very nearly (but not quite) without saying that the literal materials that compose them—paper, cardboard, plastic, and so on—and that the industries that create and maintain them are finite, extractive, and unsustainable.

Yet, as we move through this complex cycle of imagination, iteration, harm, and survival, we would do well to turn to Tremblay’s reflections on breath as inherently (metaphorically, literally, and etymologically) aspirational. For him, avenues for violence like breath can also pathways for wishful experimentation, and while he cautions that “aesthetic experimentation cannot realistically solve breathing, or disentangle it from its status as evidence of vulnerability to violence or neglect,” he also notes that “aesthetic experimentation can…produce a breath that exceeds this status. The cultivation of such excess makes breathing, more than an index of crises, a resource for living through them.” Similarly, while solo journaling games are not themselves inherently subversive objects, examining and playing them critically reveals generative ways of looking at, thinking about, and negotiating with queer subjectivities and experiences. They help us attune to the slip and slide of unstable critical subjectivities within rigid, gamic systems and embrace the unruliness inherent in our material relations.

–

Featured image from Henrique Alvim Corrêa’s Illustrations for The War of the Worlds (1906). Available at the Public Domain Image Archive: https://pdimagearchive.org/images/34130069-1049-45a5-9e9a-0fddde108dd5/.

–

Abstract

In this article, I detail key experiences in my playthroughs of two solo journaling games that engage explicitly with environmental themes and use them to model material interventions into queer theory. In the first game, The Crushing Dark: A Solo Journaling RPG (2021), I explore the fragility of subjecthood and by documenting my player character’s (PC) attempts to maintain the integrity of a bathysphere against an inhospitable, albeit beautiful, submarine world. The second game, Dwelling: A Solo Game for Ghosts (2021), I investigate the erotic possibilities of memory as a ghost floating through rooms, creating memories, and making marks. I explore these vulnerabilities materially through the environmental humanities concepts of precarity and porosity. I argue that, while this intervention is not unique to the format of solo journaling games, this genre is a generative place of study because its format highlights the precarity of the player. To play one of these games is to engage head-on with queer understandings of unruly subjecthood and precarity—it is no wonder, therefore, that the tone of so many of these games is introspective melancholy, and that journeys through these games are so often journeys into oneself at least as much as they are journeys through a game’s world. Yet a self never exists in isolation but is always located in an environment which permeates as much as it shapes. Understanding our entanglements with slippery, sticky, or otherwise fluid media helps us to reconceptualize the fixedness of apparently static social structures and hierarchical relationships.

Keywords: environmental games, solo games, TTRPG, queer theory, journaling, memory, affect, materiality, subjectivity

–

Brandon Blackburn (he/him) is a 4th-year doctoral candidate in Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Irvine. His research examines intimacy with and within the fractures of rigid structures of play. By looking at depictions of monstrosity and affects of horror through the lenses of race and queerness in playable media, he seeks to articulate both resonances and slippages between players and the games they play. His work has been published in TOPIA and Amherst College Press.