“…The mysterious and exotic Orient, land of spices and warlords, has at last opened her gates to the West.” —TSR, Inc.

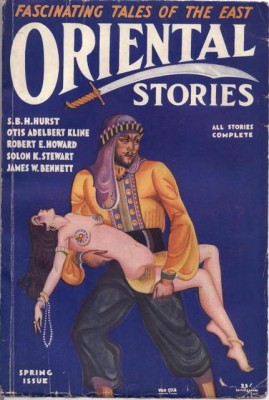

The above blurb was printed on the back of the 1985 “official” Advanced Dungeons & Dragons supplement Oriental Adventures. Tellingly, it reveals much about the target reader. The reader here is assumed to be of western descent, specifically American, Canadian, or British. They find the “Orient” mysterious and exotic, notable for both its colonial bounty—the riches of the spice trade—and its war-torn landscape, made famous by warlords like Genghis Khan. Finally, the reader is assumed to perceive the Orient as somewhat feminized, possessing a subordinate relationship to western nations, culture, industry, and governance. A skeptical reading of this blurb suggests that the success of Oriental Adventures was predicated upon a racist and sexist culture of American, Canadian, and British gamers who were interested in barnstorming though the gates of the “Orient” to confront barbaric hordes in order to plunder the land’s riches. A more generous reading would suggest that a racist and sexist culture of American, Canadian, and British gamers simply wanted to develop a finer sense of appreciation for the another more “exotic” culture. Either way, it is clear that Oriental Adventures revels in what cultural theorist Edward Said refers to as orientalism—a way of reducing the complexity of eastern culture to a set of problematically racist and sexist stereotypes. This essay explores how orientalism was schematized as a set of game rules in Dungeons & Dragons and argues that we can observe how the affiliated racist and sexist attitudes are articulated within the game’s procedural logic.

This essay looks at how notions of race and culture inform broader practices of game design and representation. I am judiciously reviewing material from Dungeons & Dragons, as it was both central to discussions of role-playing in the 1980s and tremendously influential in the history of game design. Although some games like 2005’s Jade Empire have followed explicitly in the tradition of Oriental Adventures, this essay shows its impact on the discourse of game design more broadly. In particular, the influence of orientalism can be traced through game mechanics governing comeliness, non-weapon proficiencies, and alignment in games featuring role-playing elements.

Oriental Adventures was both a critically lauded and commercially successful supplement for Dungeons & Dragons. It was rebooted in 2001 for compatibility with Dungeons & Dragons 3rd edition, this time winning an ENnie award. The original 1985 supplement, as described in the introduction the 3rd edition reboot, was influenced by the 1980 television miniseries Shogun and the 1979 role-playing game Bushido. As such, Oriental Adventures is very much indebted to the interest in eastern culture which was popularized in America, both by Kurowsawa’s samaurai in the late 1950s, and the kung fu film genre—typified by Bruce Lee in Enter the Dragon (1973)—in the early 1970s. The game is written for a presumably western, white, male audience who is interested in exploring the cultural tropes of the eastern world.

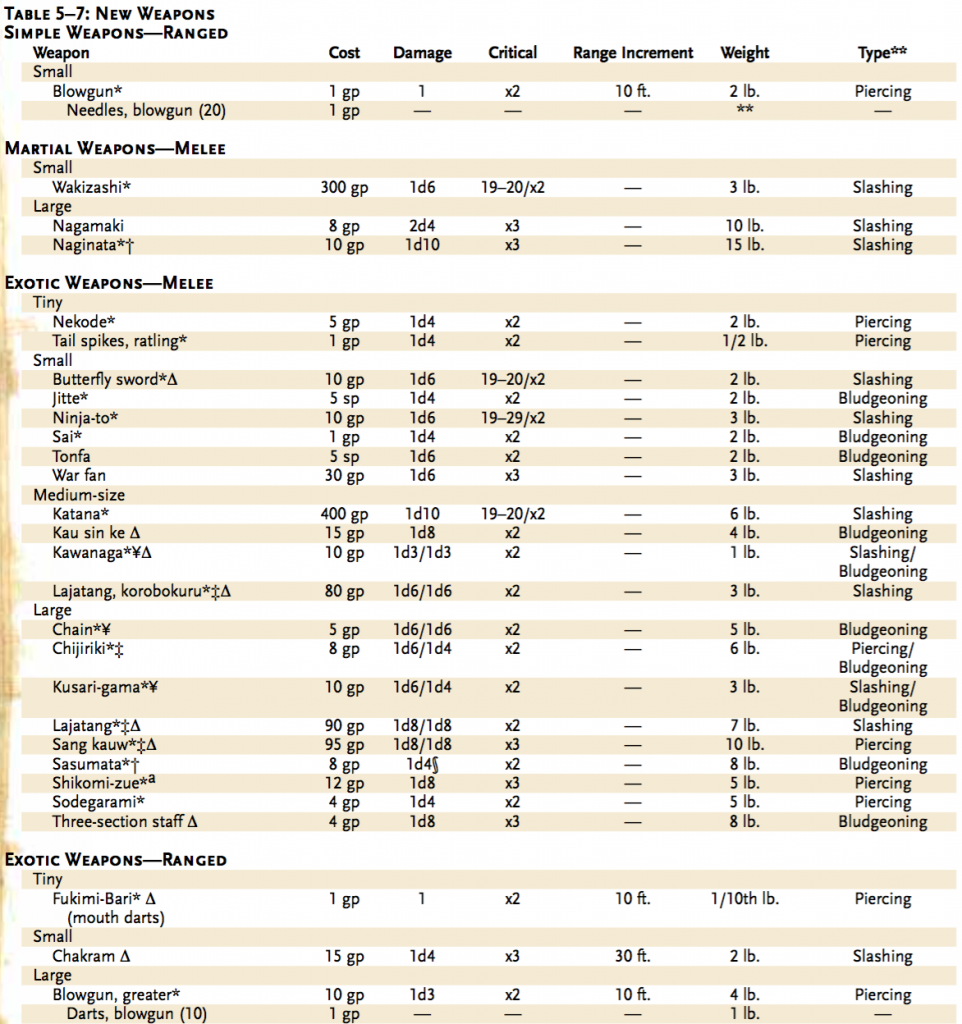

Can Dungeons & Dragons even exist without Orientalism? For all of the excellent work that Mike Mearls and Jeremy Crawford have done in designing a world that fosters a more critical dialogue around gender though 5th edition Dungeons & Dragons (2014), overtones of orientalism pervade the text, adorning the Player’s Handbook like sequins. First, there are illustrations: an East Asian warlock, a female samurai, an Arabian princess, an Arab warrior, and a Moor in battle, to name a few. Then, there are mechanics: the Monk persists as a class replete with a spiritual connection to another world via the “ki” mechanic. Scimitars and blowguns are commonly available as weapons, and elephants are available for purchase as mounts for only 200 gold. Although all of these mechanics are presented with an earnest multiculturalist ethic of appreciation, this ethic often surreptitiously produces a problematic and fictitious exotic, Oriental figure. At this point, given the embrace of multiculturalism by the franchise, it seems that the system is designed to embrace the construction of Orientalist fictional worlds where the Orient and Occident mix, mingle, and wage war.

For Edward Said, “orientalism” means many different things. Orientalism is an antiquated yet pervasive (in 1978) academic way of understanding the Orient. Orientalism is also philosophical mode of comparing western (known) culture, people, customs, and society to the exotic eastern unknown. Finally, orientalism is the practice of reducing the people, religions, nations, geography, and cultures of east to a singular and stereotypical imaginary. In Said’s words, “a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient.” These three definitions of orientalism work together to produce an oppressive system of knowledge of around the Orient systematically reproduced in institutions such as academia, authoritative texts such as encyclopedias, dictionaries, and histories, and popular culture such as kung fu movies, bric-a-brac in head and curiosity shops, role-playing supplements. Notably, orientalism is closely related to the figure of the Orientalist—the western researcher who acquires cultural knowledge from the eastern world in order to define, restructure, and produce an authoritative vision of what the Orient is. Although we might criticize the position of authority that the Orientalist maintained as well as the stereotypes that were developed and disseminated through their work, it is important to remember that the Orientalist saw themselves as somewhat “heroic,” cultivating a popular appreciation for eastern culture.

These contending factors—the related notions of appreciation and authority—are key to understanding how orientalism, despite the best intentions of Orientalist authors, persists as an ideology. Although Gary Gygax envisioned a campaign setting that brought a multicultural dimension to Dungeons & Dragons, the reality is that by lumping together Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Mongolian, Philippine, and “Southeast Asian” lore he and co-authors David “Zeb” Cook and Francois Marcela-Froideval actually developed a campaign setting that reinforced western culture’s already racist understanding of the “Orient.” Appreciation and authority are conjured, in part, through the manual’s form. Oriental Adventures, like all Dungeons & Dragons manuals is written in a comprehensive and exhaustive style that mimics the form of an encyclopedia in its organization. Apart from the tables, charts, and illustrations that had, at this point, become standard fare in role-playing supplements, Oriental Adventures also included a 72-work bibliography that simultaneously relates an appreciation of and authority over the Orient. This structure, the encyclopedic, although derived through practices of appreciation becomes ultimately an exercise in producing an authoritative source in what does and does fit into the imaginary of the game’s world.

Although the manual’s form speaks to the interest of Gygax and company in displaying both appreciation and authority toward the Orient, it also encouraged players to develop a similar disposition. In “A Step Beyond Shogun…A Reader’s Guide to Adventuring in the Orient,” David Bunnell offers a review of the literature contained in the Oriental Adventures bibliography. In Bunnell’s words:

All the books I have mentioned are excellent resources for the gamer who wishes to add that extra flavor to his campaign. I enjoy role-playing, and I started (as most of us did) by playing the medieval ancestors that I imagine that I once had. Now, after a great deal of reading, I am ready to try to role-play in a totally different feudal culture. I don’t know if I’ll ever truly understand the Japanese culture, but I will certainly enjoy myself while learning.

It is by learning the Orientalist texts listed in the Oriental Adventures bibliography that Bunnell felt able to authentically role-play characters in a non-western feudal society. Simply put: by cultivating a sense of cultural appreciation, Bunnell was able to authoritatively produce a feudal Japanese world for himself and his players. “A short survey of a few especially significant books in the field may help these bewildered [Dungeon Masters] get back on the path toward successful Oriental gaming.” Clearly “success” for Bunnell is linked to both the appreciation of the Orientalist texts as listed in the Oriental Adventures bibliography and the authority that is cultivated through this form of appreciation.

The secret to understanding the forms of racism that accompany Oriental Adventures is recognizing that it is assumed that the characters played will be oriental—whatever that means. This sometimes means connecting the dots and questioning why certain game mechanics have been included or altered. Take for example the new statistic that is offered: “Comeliness.” At face value, Comeliness seems like a simple modification to the game’s core mechanics, which had already been taking into account “Charisma“ for the better part of ten years. But unlike Charisma, Comeliness is meant to speak more directly to beauty: “While Charisma deals specifically with leadership and loyalty, Comeliness deals with attractiveness and first impressions.” Comeliness becomes a game mechanic in Oriental Adventures because the feminized Asian man is part of the Oriental imaginary. Where the assumed male player in Dungeons & Dragons enjoyed a Charisma score which determined the extent to which his masculine charm would win the loyalty of his men on the battlefield, the Oriental man’s beauty can be apprehended through the Comeliness statistic—a dubious honor previously reserved only for women in Len Lakofka’s unfortunate article “Notes on Women and Magic.” Thus the introduction of the Orient in Dungeons & Dragons invokes a radical rethinking of what constitutes a “man,” and the sexist and racist precept that Oriental men must be evaluated also in terms of their physical beauty.![]()

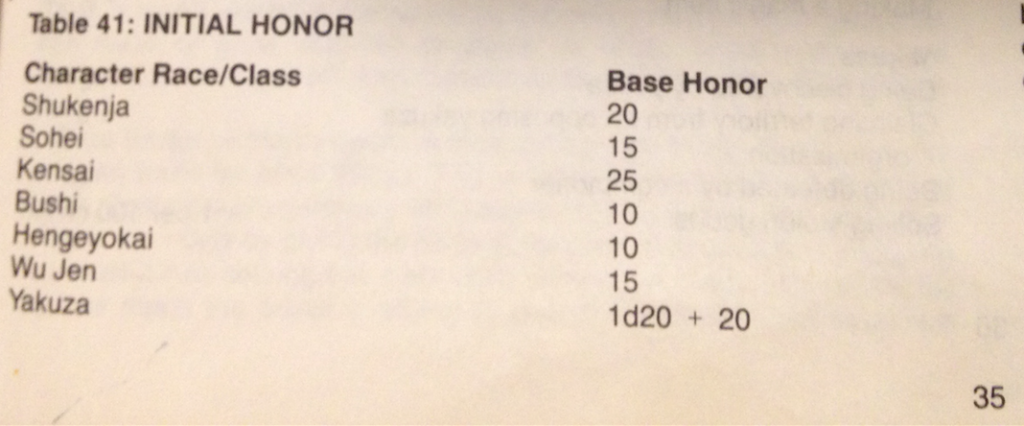

![]() Not only does Oriental Adventures encourage players to think through how to quantify the appearance of Oriental men and women, it also encourages players to quantify their social worth. In addition to the implementation of Comeliness, Oriental Adventures also presented players with a system to consider character honor. Honor in an Oriental Adventures campaign is related to a character’s sense of character, value to society, and overall trustworthiness. Unlike honor for a paladin in a traditional Dungeons & Dragons campaign, Honor in this context has been detached from the ethical matrix of alignment. Honorable characters in Oriental Adventures can be evil, and dishonorable characters in Oriental Adventures can be good. Honor, like Comeliness, is also quantified. Characters are awarded honor points by the game master: as few as zero and as many as one hundred. The imposition of an honor system within the rules of Oriental Adventures makes clear what had been invisible and taken for granted in Western campaign: unlike Western characters, the social worth of Oriental characters is always suspect.

Not only does Oriental Adventures encourage players to think through how to quantify the appearance of Oriental men and women, it also encourages players to quantify their social worth. In addition to the implementation of Comeliness, Oriental Adventures also presented players with a system to consider character honor. Honor in an Oriental Adventures campaign is related to a character’s sense of character, value to society, and overall trustworthiness. Unlike honor for a paladin in a traditional Dungeons & Dragons campaign, Honor in this context has been detached from the ethical matrix of alignment. Honorable characters in Oriental Adventures can be evil, and dishonorable characters in Oriental Adventures can be good. Honor, like Comeliness, is also quantified. Characters are awarded honor points by the game master: as few as zero and as many as one hundred. The imposition of an honor system within the rules of Oriental Adventures makes clear what had been invisible and taken for granted in Western campaign: unlike Western characters, the social worth of Oriental characters is always suspect.

My thesis is that the essential aspects of modern Orientalist theory and praxis (from which present-day Orientalism derives) can be understood, not as a sudden access of objective knowledge about the Orient, but as a set of structures inherited from the past, secularized, redisposed, and re-formed by such disciplines as philology, which in turn are naturalized, modernized, and laicized substitutes for (or versions of) Christian supernaturalism.

The game makes clear the comparison between Oriental honor and the Christian ethic. Western honor, epitomized by the paladin, maps cleanly onto the values that we associate with good or evil in Dungeons & Dragons alignment system. Good players are grounded through the dogma of the Judeo-Christian imagination, which associates good deeds with the good and honorable life. By proposing a system to govern honor that operates independent from the traditional politics of alignment, Oriental Adventures re-forms and contorts the Oriental family to co-exist as secular within a Judeo-Christian alignment table.

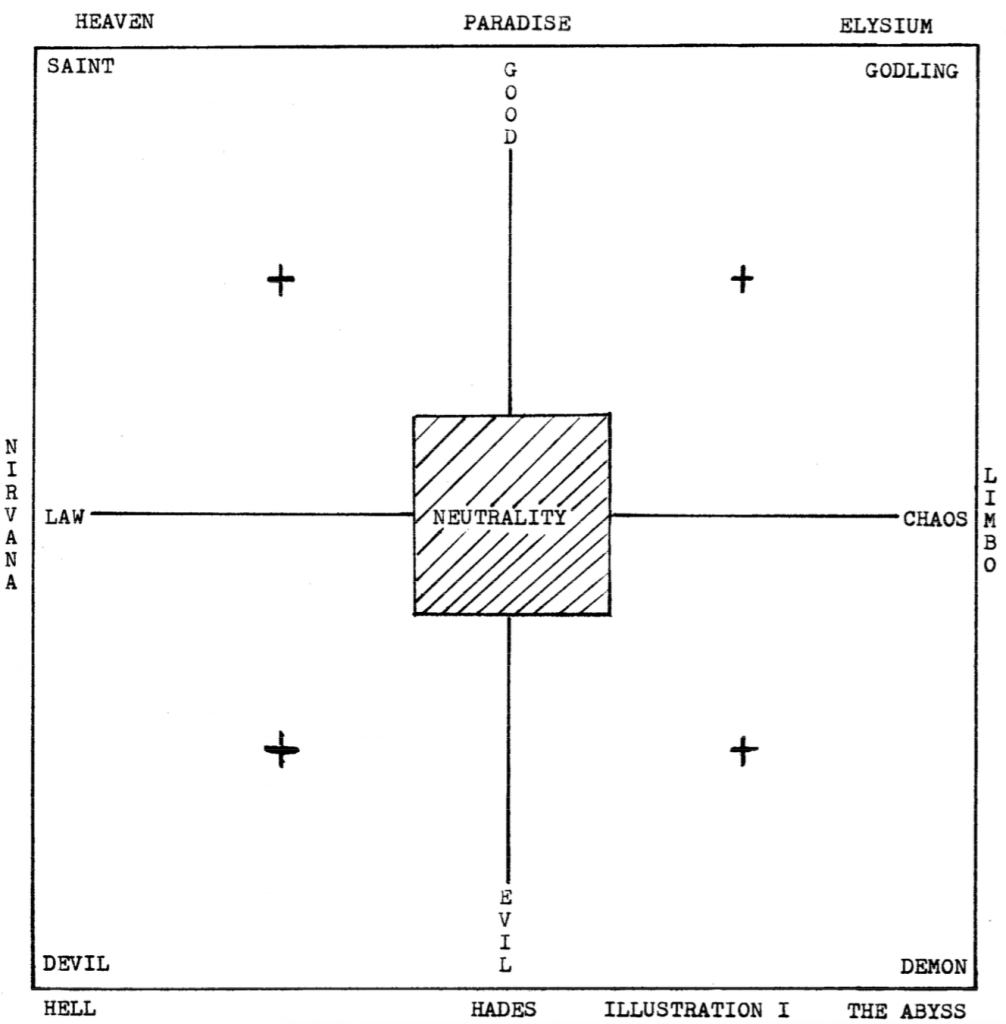

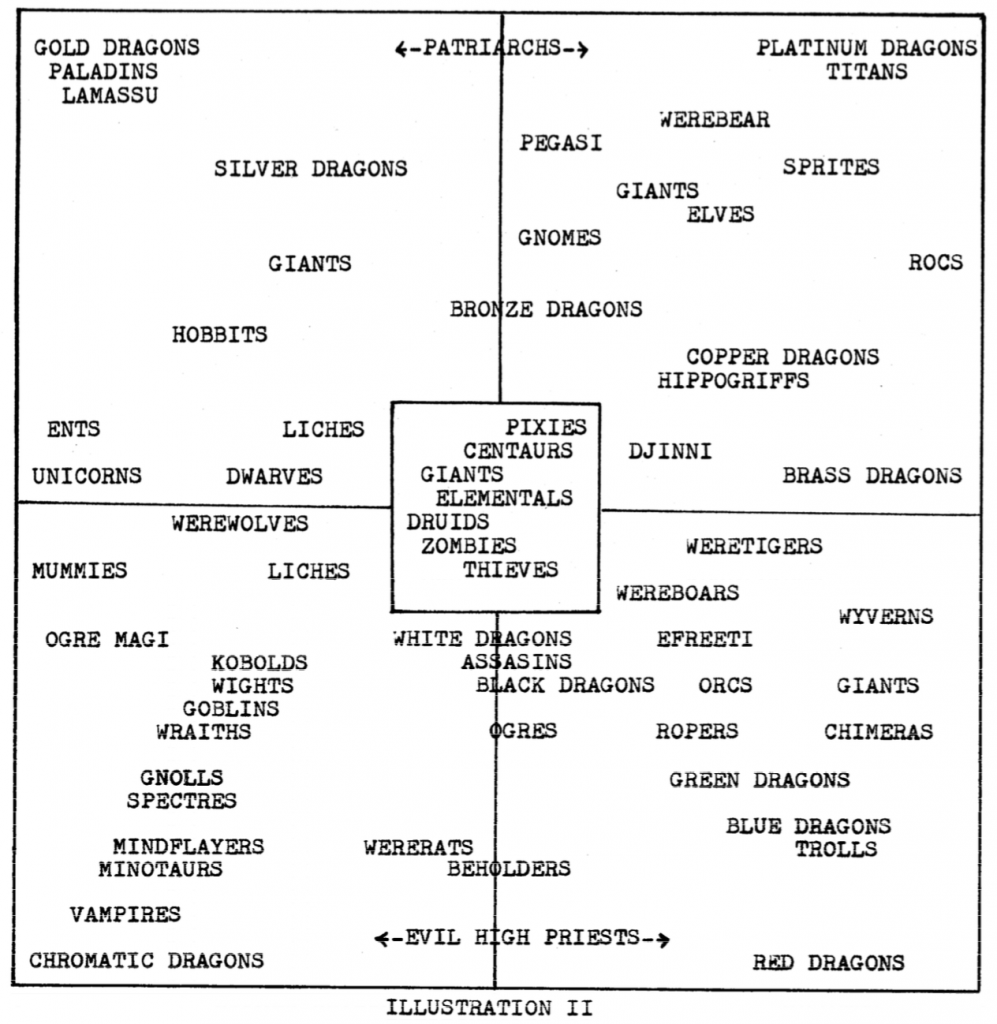

Gygax’s invention of alignment in Dungeons & Dragons alone is replete with the tropes of Orientalism. It is a fascinating effort to juxtapose the exotic creatures and planes of a multicultural religious pantheon into the legal and religious framework of 1970s Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. By this I mean that Dungeons & Dragons’ alignment system is a uniquely American (Law vs. Chaos) and Christian (Good vs. Evil) way of understanding the world. Gygax’s early attempts to map both mythological creatures and divine landscapes upon this strata reflects this. Here, the Buddhist idea of “Nirvana” co-exist within the Christian poles of “Heaven” and “Hell”(see below). It is made to contort the polemical religious logic of Christianity. Creatures from the Arabian Nights mythology are also made to conform to the dynamics of alignment, yet they are placed across the grid from Christianity—away from law: Djinni are good, but chaotic; Efreeti are evil, but chaotic. Within the logic of alignment, Christian ideology is ordered, controlled, lawful while all the rest of the world skews toward the chaotic Orientalist (and mythological) pole which opposes it.

One exception to this analysis is Gygax’s analysis of Buddhism’s Nirvana which aligns itself with law and neutrality, while simultaneously evading the binary Christian constructions of Heaven and Hell (and therefore Good and Evil). Appreciation of Buddhism as another path toward lawful spiritual conduct is given here as Gygax simultaneously invented an authoritative guide to alignment. Because alignment has become so pervasive a mechanic for guiding consistent role-playing practices in role-playing games, it is important to recognize how Gygax’s work as an Orientalist has contorted non-Western spirituality and behavior into a system of knowledge that is readily adaptable for use as a game mechanic. In other words, all games which make use of an alignment system are, to some extent, relying on a system which takes Judeo-Christian values for granted and essentializes all other ethical and spiritual thinking onto a grid governed by its boundaries.

Both Comeliness and honor show how Gygax’s appreciation for eastern culture is articulated through a set of game mechanics that both quantify this culture and compare it to the invisible and assumed dynamics of Western American culture. This mode of reductionism encourages players to imagine eastern culture as if it could be contained by a single text and represented through a single Oriental campaign setting. At its most problematic, Oriental Adventures represents a complex and multifaceted set of cultural interests through a single and singular set of game mechanics.

Non-Weapon Proficiencies

Having established that the Oriental Adventures manual is a clear example of an Orientalist text, we can now look at the supplement’s impact on the Dungeons & Dragons system, the invention of “non-weapon proficiencies” in particular. Here I argue that there is an isomorphic relationship between the abstraction of culture into a reductionist Orientalist imaginary and the newly minted non-weapon proficiency that reduces culture into a controllable and quantifiable procedural function. Despite the problematic nature of this reduction, the introduction of non-weapon proficiencies allows for players to consider how the game’s mathematic world might exist outside of combat. Interestingly enough, the introduction of cultural game mechanics to Dungeons & Dragons prompts players to imagine how the game might transform into something more than a game derived from and simply about warfare.

The comparison to warfare is explicit in the manual. The section on “Non-Weapon Proficiencies” begins: “In addition to weapons, characters can learn proficiencies in various peaceful arts.” The logic of these peaceful proficiencies was folded into a logic parallel to that of combat or contest. Because the cultural differences of Oriental life could be accommodated by an honor system which established a value to life outside of the American standbys of wealth and eternal reward, modes of conflict that deal with honor specifically were built into the system. Gygax explains that the “victors of such contests gain honor and experience for their skill, while those defeated lose honor. The outcome of contests can greatly affect a character’s social position.” Within these peaceful, non-weapon profiencies is an ideal folding of an imagined Oriental everyday life into the logic of honor, social standing, and familial worth.

Although some of the rules that were developed around non-weapon proficiencies that would have been at home in Western settings as well (Agriculture, Running, Carpentry, and Herbalist to name a few) many are distinct to Gygax’s Orientalist world. Most notable here is the distinction of specificity between those proficiencies known by nobles and those by commoners. The implication here is that the interesting aspects of Oriental culture lie within the hands of the elites, whereas the culture of the common people is barely distinguishable from that of the Western common folk. To make this comparison compare the specificity of two lists, one made for nobles in the subset “Court Proficiencies” which includes Caligraphy, Etiquette, Falconry, Flower Arranging, Heraldry, Landscape Gardening, Noh, Oragami, Painting, Poetry, Religion, and Tea Ceremony to one made for common folk in the subset “Common Proficiencies” which includes Agriculture, Animal Handling, Cooking, Dance, Fishing, Games, Horsemanship, Hunting, Husbandry, Iaijutsu, Juggling, Music, Reading/Writing, Sailing Craft, Singing, Small Water Craft, and Swimming. These lists further the classist understanding that “culture” is possessed by elites and inaccessible to poor people.

This dichotomy relates to Said’s theory of Orientalism because it reflects the sources used to produce Orientalist discourse. Because the Orientalist’s understanding of the Orient was limited to documents which were published by those in the elite sectors of eastern culture, the whole of the Oriental imagination is focused around an idea of culture which privileges the rituals of those of the upper class and court.

Real and Symbolic Violence

It is difficult to judge the merit of this transformation. I for one feel that it definitely cannot be seen as an adequate sense of compensation for the violence of Orientalism. Although Dungeons & Dragons and other role-playing games owe Oriental Adventures a debt of gratitude for seeding the ideas which would eventually lead to robust crafting mechanics and secular systems of character development, these systems are in truth based upon a discourse that values, appropriates, and exploits “exotic” races, customs, and cultures. For all of the life these game mechanics now breath into the games we play, they must be regarded as a final sort of symbolic violence that renders the rich traditions of Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa invisible. For example the mechanics that govern agriculture or farming in Fallout 4 (2015) have no relation to the histories of knowledge that have been lost in this process of abstraction. We forget that all of the rich ways that cooking has been developed as a mechanic in role-playing games hold an inextricable historical relationship to the ways that cooking was fundamental to the everyday life of common folk in the Orient.

What’s more, we lose the most important connection between non-weapon proficiencies and war: the fact that non-weapon proficiencies were initially supposed to be peaceful. Because many role-playing games seek to enfold non-weapon skills within the logics of combat and acquisition (Cooking helps to restore wealth, Etiquette may help to gain economic favor in the court or to prevent combat, Crafting is often a way to develop better weapons and armor) they participate symbolically in colonialism’s modern legacy. They reduce the richness of non-western culture to a set of “non-weapon proficiencies” which can be developed and exploited to further the Western war effort.

The value of multiculturalist design in role-playing games is yet to be seen, however. On the one hand, it offers a space of inclusion for players who were once stymied by the commonplace white supremacist worlds inspired by Sword & Sorcery fiction in early role-playing game design. At the same time, the ethic of multiculturalist design in role-playing games still reads as Orientalist and appropriative. A way to engineer a fiction of diversity in games engineered by white men who, much like Gary Gygax, long to enjoy and celebrate the exotic, while also profiting from it. The fiction of diversity, as Edward Said would note, is dangerous because it promotes a singular imaginary of diverse people. It allows for a singular idea of the Orient, which is always already the object of violence, appropriation, domination, and conquest.

This essay has shown ways in which the Dungeons & Dragons supplement Oriental Adventures fits Edward Said’s criteria of an Orientalist text. It shows this by revealing how the supplement’s Comeliness and Honor mechanics are the result of a racist discourse that reads Oriental men as feminine and Oriental people against the lawful values of Christianity. Beyond this, it also considers how the invention of peaceful, non-weapon proficiencies are derived from a classist understanding of what Oriental culture is. Despite these racist, classist, and sexist values, the legacy of Oriental Adventures persists in many role-playing games today in the non-weapon proficiencies and skills given to characters. Finally, it argues that we must question the implementation of non-weapon proficiencies in many of today’s role-playing games because of the symbolic violence they produce when placed in a synergistic relationship with the game’s core combat mechanics. If we are to resist the legacy of Orientalism in role-playing games, we must work to recover forgotten aspects of Asian, Middle Eastern, and North African culture which have been lost within the abstraction of game design.

–

Featured Image “miniatures” by Allan @Flickr CC BY-NC.

–

Co-Editor-in-Chief, Aaron Trammell, PhD is a Provost’s Postdoctoral Scholar for Faculty Diversity in Informatics and Digital Knowledge at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. He earned his doctorate from the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information in 2015. Aaron’s research is focused on revealing historical connections between games, play, and the United States military-industrial complex. He is interested in how military ideologies become integrated into game design and how these perspectives are negotiated within the imaginations of players. He is the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the journal Analog Game Studies and the Multimedia Editor of Sounding Out! In 2014, Aaron co-edited a volume of Games and Culture with Anne Gilbert entitled “Extending Play to Critical Media Studies.”