D&D is a deeply mechanical game. The DM has countless texts at their disposal, including lengthy rules related solely to their role within the game. 1 On the other side of the table, the players have their own individual rules, lists of spells, and enough dice hoarded away to make a dragon jealous.2 This paper shall highlight the mechanical elements of D&D, demonstrating how they interact with and against the vampire tradition. Considering each element in practice, combined with narrative and role-playing illustrates the value and unique nature of D&D within the vampire tradition. The first core mechanic this paper will examine is alignment. The use of alignment facilitates an examination of morality within the vampire tradition, while highlighting the inconsistencies of strictly managed morals in a game such as D&D.3 This paper shall also begin to establish Stoker’s vampire Dracula as an important character of reference and contrast for Strahd.4 Both vampires have clear similarities that present themselves differently due to the variation in their literary mediums. Expanding on Strahd’s place within the tradition, the combat mechanics of the vampire shall be compared to Dracula, indicating the influence the vampire tradition has had on the D&D creation. From here, the paper shall look at the concept of agency and player led narrative. As D&D strays from traditional literary form, there is an extraordinary amount of room for PC’s free roaming.5 This section will look at the way agency is used in D&D, both for the benefit of the vampire tradition, and at the possible detriment of D&D as a game system. Finally, this paper will break down the key mechanic of the Tarokka deck, highlighting the marriage of mechanics and narrative. Overall, this paper, through the above points, will demonstrate how D&D’s unique mechanics work in tandem with the vampire tradition, while challenging both the tradition and game itself.

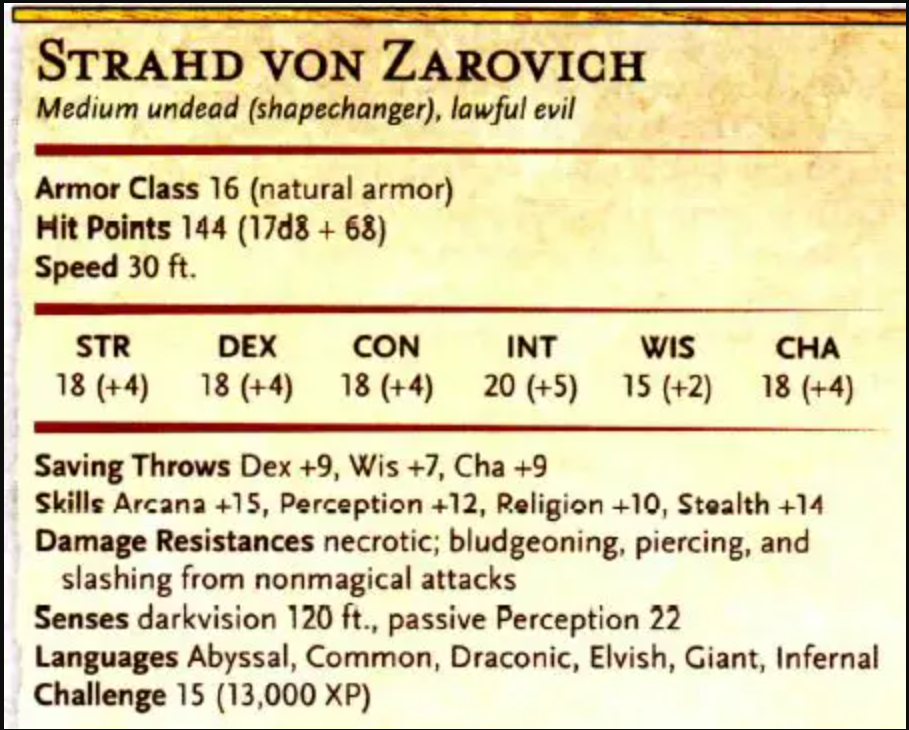

Alignment is a key feature of both PC and NPC roleplay in D&D, facilitating both free and directed narrative. Each character is given an alignment, such as Lawful Good or Chaotic Evil. These alignments form the moral compass of the character.6 A chaotic character may act irrationally, led by impulse, while a lawful one will have a set of rules governing their actions.7 The core vampire of this dissertation, Strahd, is assigned Chaotic Evil in his first presentation within Ravenloft.8 This mechanic is later changed in Curse of Strahd, as his alignment entirely flips to Lawful Evil.9 This would suggest he is both chaotic and impulsive yet level-headed and calculated throughout the campaigns. Despite this, Strahd’s suggested actions and descriptions do not change from one text to the other to reflect this change in alignment, directly contradicting the role of alignment in D&D. To better understand this concept within the context of D&D, the theory behind alignment and morality must be examined. With each edition of D&D, alignment has been updated and changed to reflect the players engaging in the game.10 Jon Cogburn and Mark Silcox explore alignment in D&D at length, considering it in relation to the player’s experience and the concept of morality within a game.11 In relation to degrees of evil Cogburn states,

In contrast, Chaotic Evil creatures are so psychologically disorganized that they are not able to refrain from acting on their desires in the short run, and hence are inevitably destructive to the community.12

Cogburn’s argument suggests that evil can only exist as a chaotic alignment.13 Supporting his argument, he suggests that good always comes from a want for order, but the same can equally be said about the concept of evil, especially in the case of Strahd.14 His primary motivations are based on his legacy and rulership of Barovia, as well as his own self centered ambition.15 Cogburn’s theory is based on 4E and while the core texts of this dissertation do not belong within this period, defining alignment, and thus morality, challenge the vampire tradition. Strict and linear morality, while key to D&D, is illogical and unbalanced in a vampire campaign. Cogburn’s argument regarding morality would suggest that Strahd is not a fit within the realms of D&D, as he exists both as Lawful and Chaotic, without any significant changes to his personality.16 The vampire tradition influences Strahd, challenging the D&D understanding of linear morality. This, thus, challenges the structure of D&D, while presenting fresh adaptations of the vampire tradition.

Breaking down this mechanic further, Strahd as an individual vampire raises further issues with the vampires of D&D. Alignment for characters such as Strahd indicate his motives and suggest the way he will go about them. For example, he views himself as the ultimate pinnacle of perfection when it comes to the rulership of Barovia.17 As outlined in Curse of Strahd,

“[Strahd considers if] any of [the players are] worthy to be his successor or consort. (Eventually, he decides that none of them can replace him as master of Barovia) … If Strahd senses evil in a person, he cultivates that tendency by offering to turn that character into a full-fledged vampire after helping Strahd destroy the rest of the party. Ultimately, Strahd doesn’t honor his promise, instead turning the character into a vampire spawn under his control.”18

This may appear to be a small detail in the context of a large campaign, but small details such as this direct the DM in their acting and portrayal of Strahd. As the vampire in Curse of Strahd sizes up these new visitors, his alignment as Lawful Evil becomes ambiguous, as it is encouraged that Strahd directly interacts with the players whenever possible, literally bringing himself straight to the players doorstep.19 The vampire is said to be “toying” with the players, “terroriz[ing]” and “goad[ing]” them.20 His constant presence, whether physical or remote, becomes semi omniscient, as he becomes both allusive and overly familiar to the players. Strahd’s suggested actions do not coincide with his alignment. The way he is presented to the players can thus vary depending on the DM’s knowledge of Ravenloft, as well as understanding of Strahd’s alignment versus his description and character within Curse of Strahd. Krzywinska explores the overlap of gaming and the players themselves in depth, demonstrating the mechanical and narrative overlap of gothic gaming.21 Strahd is Lawful Evil, thus the DM may opt for him to be played as a corrupt ruler, an evil diplomat, using minions to spy on the players while they journey through his land.22 In stark contrast to this, it is encouraged, as mentioned above, that Strahd himself comes directly to the players. This strongly contradicts elements of his alignment, demonstrating chaotic behavior that puts himself and his motives in danger, especially as the story progresses. He has it within his means to rely solely on the updates of communities such as the Vistani yet chooses to get personally and physically involved.23 He is both the level-headed aristocrat and the chaotic impulsive monster of the night. There is simply no single correct way to play Strahd. Despite this, mechanics such as alignment indicate that variation in the vampire tradition can be tested and played with constructively. This critiques both the vampire tradition and D&D, challenging each other in turn.

The mechanics of D&D have the potential to highlight literary influence from the vampire tradition. A study of Strahd’s character, both in narrative and in mechanics, quickly highlights the influential presence of Dracula.24 The influence and impact of a player’s own cultural awareness in itself acts as a mechanic within the game. One of the most significant mechanics of D&D is the player themselves.25 A massive practical element that has undeniable importance in the running of D&D campaigns is the players pre-existing understanding of the content they are dealing with.26 This, in most cases, relies on the players having a level of understanding or awareness of general and generic fantasy elements, such as that presented by James in relation to the adaptation and growth of fantasy literature.27 This is complicated in the world of Barovia as it simply is not, and cannot be, pure fantasy. Barovia, the realm Strahd resides over, mixes fantasy motifs with those of horror and gothic.28 While not every player will have read the entirety of Stoker’s Dracula, the presence of the vampire tradition in popular culture negates the need for any extensive reading prior to playing.29

Adler discusses the influence of the vampire tradition on massively popular adaptations such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer.30 In relation to adaptative genre, Adler suggests that genre is fluid, needing to adopt the form it is taking while intricately interweaving the existing tradition into the new form.31 As Buffy pulls from the vampire tradition it also adapts to appeal to its new audience.32 A further example of cultural awareness influencing modern media can be seen in Scooby Doo and the Ghoul School.33 Here, the vampire is humanized, similarly to Angel in Buffy.34 The vampire girl from Scooby Doo is a direct relative of Dracula, depicting the same gaunt face and bat form linked to the character, while presenting the monster in a friendlier light for a children’s audience.35 Returning to D&D and Strahd, the DM may very well choose to pull heavily from the character of Dracula due to the influence of popular culture. This is all the more likely due to the direct references to Dracula in Strahd’s character and mechanics. A key example of this can be found in Strahd’s combat mechanics. Both of these men perform unnatural acts during combat, transitioning to a beastly state. Strahd has the ability to “Spider Climb: Strahd can climb difficult surfaces, including upside down on ceilings, without having to make an ability check.”36 It is also mentioned that Strahd cannot enter a residence without permission from a resident, as well as his vulnerability to running water, a stake to the heart, and sunlight.37 These are clear references to Dracula’s character:

But my very feelings changed to repulsion and terror when I saw the whole man slowly emerge from the window and begin to crawl down the castle wall over that dreadful abyss, face down, with his cloak spreading out around him like great wings.38

The influence of Dracula does not end in combat mechanics. Expanding on both mechanics and cultural influence, additional content can allow for a higher degree of narrative freedom in D&D.39 The inclusion or exclusion of optional modules shapes the presentation of the vampire tradition within the game. A key example of one of these optional additions is in the Death House module of Curse of Strahd.40 The inclusion of this section acts as a transitional point for the players, leveling them up and introducing them to some key players and attitudes in the world they have just entered.41 The core story elements of this house focus on a family that engaged in cult activity centralized around the figure of Strahd, resulting in the death of their children Rose and Thorn, who appear to the players as ghosts, luring them into the house.42 As players traverse the area, they are eventually clued into the fundamental issues of the family, such as the mistreatment of the children, and the cult sacrifices within the basement. One room contains a shrine dedicated to Strahd, introducing the characters to their largest rival in the game. The suggested description states

“This room is festooned with moldy skeletons that hang from rusty shackles against the walls. A wide alcove in the south wall contains a painted wooden statue carved in the likeness of a gaunt, pale-faced man wearing a voluminous black cloak, his pale left hand resting on the head of a wolf that stands next to him. In his right hand, he holds a smoky-gray crystal orb.”43

This is often the first meeting that players have with any representation of Strahd. The gothic atmosphere is clearly set through the daunting presence of the statue, as well as the skeletal remains lurking in the corners of the room. Strahd’s description indicates direct reference to the vampire tradition. Stoker’s vampire has direct connotations with wolves, and the gaunt face and illustrious cape are well known indicators of the vampire figure.44 It is apparent that the creators of Strahd are heavily drawing on the pre-existing vampire tradition, using it to influence the mechanical storytelling of the game.

“Somewhere high overhead, probably on the tower, I heard the voice of the Count calling in his harsh, metallic whisper. His call seemed to be answered from far and wide by the howling of wolves. Before many minutes had passed a pack of them poured, like a pent-up dam when liberated, through the wide entrance into the courtyard.”45

The presence of this statue does not simply suggest links to a pre-existing vampire tradition but alludes to the unique contribution of D&D vampires. The presence of the smoky grey orb is a symbolic link to the Vistani community and the Tarokka deck.46 The culmination of pre-existing tradition, adaptive symbolism, and the mechanical presentation of each of these elements found within this singular instance demonstrate the uniqueness of D&D’s contribution to the tradition. Small elements of narrative provide the characters with the means to analyze and understand the context of the game, and the vampire figure. With this information at their disposal, the characters may interact in any means they determine appropriate, whether that be respectful, due to the implied importance of this statue, or disrespectful due to the visage and allusion of power this statue presents. Here is where the mechanic of player agency truly comes into play, directly influencing the narrative and thus its contribution to the vampire tradition.

also holds reference to sages and prophecy. The imagery pays homage to the Vistani people of Barovia.

The Death House module provides the PCs with a gothic playground, allowing them to establish their own understanding of the tradition. The penultimate instance of this occurs once PC’s reach the basement dais where ghostly cultists demand a sacrifice. This section, while narratively led in the mind of the players, is entirely formulaic and mechanical.47 Characters must sacrifice a living creature, and for this to be a success, the creature must die. Players can learn this information through a successful intelligence roll, where the dice totals more than eleven.48 If the demands of the cultists are not met, a monster emerges from the musky water surrounding the dais.49 At this moment, the players are left to determine how gruesome they themselves are willing to get within the campaign. Players may choose not to engage or sacrifice a small creature that can be summoned magically. This scene may also prompt players to act heroically for the benefit of the party. In a particularly gruesome and unexpected example, players have killed themselves or other players, setting either an incredibly morose and somber, or a tense and uneasy tone for the rest of the campaign. While a heavily mechanical scene, moments such as these shape the game, determining the level of gore in this varying representation of the vampire tradition.

As demonstrated thus far, the vampire tradition is revisited and adapted within D&D. It challenges D&D mechanics that do not align with the tradition, while challenging the concept and presentation of a vampire, making Strahd a fresh contribution to the overall tradition. The concept of player led narrative challenges the vampire tradition, proposing flexibility in the tradition and manner in which PC’s comprehend said tradition. Despite this, the constraints of the vampire tradition require some form of isolation to highlight the dread of the gothic setting. This presents an issue within D&D as PC agency is vital to enjoyable gameplay. To visibly “railroad” players into one story is entirely against the nature of D&D.50 Expanding on the above discussion of mechanical agency in the Death House module, the mode in which players actually arrive in Barovia further challenges the concept within D&D and the vampire tradition. D&D uses narrative as a key feature of the game, unlike games such as Warhammer where narrative is a secondary element.51 The focus on narrative over pure combat is discussed by Glas in his work, highlighting that D&D “offer[s] a free-flowing mix of storytelling and acting … supported by wargaming’s instrumental rules and structures.”52 An excellent example of where D&D employs rules and structures within free flowing storytelling is in the removal of PC agency when entering Barovia. Agency, or at the very least the illusion of agency, is of utmost importance to D&D.53 When entering Barovia PC’s are swept up in a foreboding fog that removes their ability to leave Barovia.54 The fog forces the PC’s to stay in Barovia, inflicting damage on PC’s who attempt to leave.55 This simple tool restricts the players interactions to one sole location, removing the possibility of outside help, despite the risk of changing D&D mechanics for the worse.56 This heightens the dread of the vampiric gothic setting and in turn Strahd. Strahd’s immense control and power is turned mechanical, amplifying his powerful presence and total control over his domain. Player agency challenges the form of D&D when the vampire tradition is introduced. Clever manipulation of space, such as the fog, maneuvers these difficulties, adapting both the vampire tradition and structure of D&D. The final area where this marriage of mechanics and storytelling meet combines each of the aforementioned elements in the form of the Tarokka deck.57

Marseille. Dallis uses this deck when

analyzing “The Lady of the House of Love” as

it would be similar to the Tarot used by the

Countess.

Physical tools are used sparingly and only when absolutely necessary in D&D. The Tarokka deck is a key example of such physical tools, used as a mechanic that impacts the overall narrative, while paying homage to the vampire tradition.58 In Ravenloft it is stated that “[although] Strahd can be encountered in many places, he is always encountered in the place indicated by your Fortune of Ravenloft results”.59 This refers to the location assigned to him by the Tarokka deck. Inspired by the Victorian fortune-teller, the Tarokka deck is imitative of a Tarot deck, and is used within the context of D&D by the Vistani people, a fictionalized representation of the Romani gypsy community.60 The Tarokka deck is heavily influenced by the Victorian vogue for fortune-tellers and spiritualism, often reflected within gothic texts during the period.61 Its use in the vampire tradition is not unusual by any means. Dallis explores the use of Tarot in Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber.62 Dallis argues that Tarot cards are intrinsically Gothic, as they work as a system of symbolism and meaning, they engender a wide range of literary interpretations.63 The focal point of this argument looks to the Countess within “The Lady of the House of Love”, who obsessively turns through Tarot cards to better understand her own destiny in a misguided attempt to escape fate.64 The Tarokka deck features a variety of cards, each with their own dual meanings and symbolism, representing characters, items, and locations, within the campaign.65 The purpose of the Tarokka deck is to provide the players with optional allies and tools to aid them in the battle against Strahd. Shelly Jones notes that the inclusion of the deck, unique to the Ravenloft inspired campaigns, provides the players with a large degree of replayability that not many other campaigns provide.66 The replayability of the campaign provides numerous angles of analysis and engagement with the vampire tradition. From a narrative standpoint, the variation and flexibility of the text adds to the complexities of it being a gothic adaptation, as the plot can vary greatly.67 Characters that may otherwise go unspoken to or unnoticed are suddenly brought to the forefront, while locations that may be glimpsed over now require in-depth preparation.68 This amalgamation of mechanical and narrative story telling summarises the role of D&D in the vampire tradition perfectly. Both are unnatural when combined, yet come together to create a unique adaptation of one another. Through the cards, narrative and plot is established within the Gothic setting of Barovia, while maintaining a subtle and often hidden mechanical element. The Tarokka deck is central to the understanding of adaptation in D&D due to the immense duality of them both practically and abstractly.

D&D reshapes the vampire tradition to fit its own structure, but in doing so bends itself to match the strong pre-existing understanding of the vampire. Unlike other tabletop roleplaying games, D&D builds on flexible gameplay, allowing for both structurally strict gameplay, and player led oral storytelling. The variety and movement in the genre allow for fluidity in the adaptations found within it. Understanding the mechanics that create the narrative of Strahd von Zarovich’s realm better establish him within the vampire tradition. They highlight his commonality with the genre, while equally shedding light on the unusual that forms a D&D campaign. Through understanding the elements of mechanical D&D that feed into the narrative structure of the game, such as the alignment, player agency, and the Tarokka deck, the game as a literary adaptation can be fully realized as a unique piece of adaptation.

–

Featured image is public domain from Free-Images.com.

Cite This Essay: Hewitt, Meghan. “Mechanical Storytelling in Dungeons and Dragons: Strahd in Relation to the Gothic.” Analog Game Studies 11, no. 4 (2024).

–

Meghan Hewitt (she/her) is a Masters student at University College London (UCL) on the Issues in Modern Culture M.A. She received her B.A in English Literature and History from Trinity College Dublin. Her interests involve all things monsters and horror, with a focus on interdisciplinary adaptation. Her book chapter Nuclear Societal Structures in the Fallout Franchise is forthcoming in Atomic Horror: Fears of Nuclear Power in Gothic Literature, Film and Media with Palgrave.

–