People who design live action role-playing games (larps) tend to be self-taught. Although there is a long and illustrious history of shared and embodied enactments of ‘as if’ play, the tradition of larps only stretches back less than 40 years. Larpwrights, i.e., the larp designers, learn how to design larps by doing, by collaborating, and by attending community events. However, this pioneer path is no longer the only one. The first series of actual courses on larp design have been established during the last decade, in academia and outside it. One of the earliest, the Larpwriter Summer School, started operating in 2012.

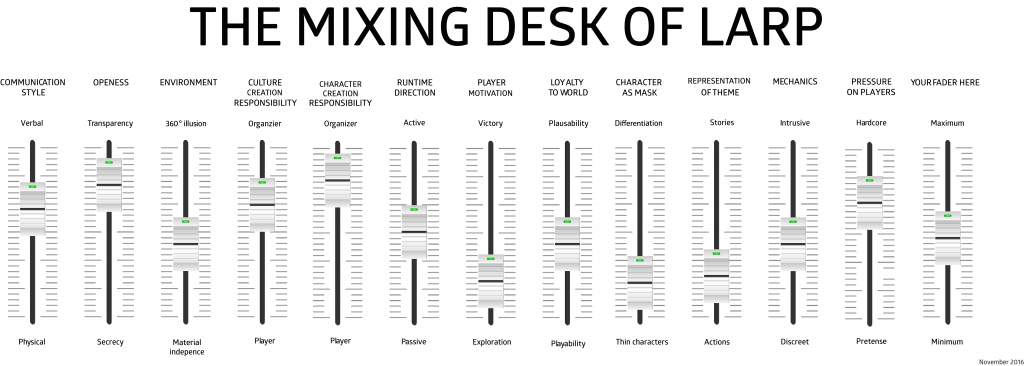

However, although there was significant debate and some literature on larp design, no holistic approaches to teaching design were found at the time. To fill this void, the main organizers of the Summer School put together a now renowned tool that originated in the Nordic larp community: The Mixing Desk of Larp.

The Mixing Desk is a frame for organizing thought, a thing-to-think-with, that helps grasp the design space of larps. It is a metaphor that attempts to communicate that the larpwright is able to play with different elements in larp, just as a technician is able to control light and sound in a concert. It is not optimized for precision or analysis, but for supporting the ideation of a designer, and helping teach larp design to people new to the practice.

This article first explains how the Mixing Desk emerged and contextualizes it as a design theory in relation to discourses in Nordic larp and game studies. Next, we explain the Mixing Desk and the ideals and reasoning behind it. We then spend most of our time with description and reflection on the thirteen faders of the current Mixing Desk. We conclude with some reflections and criticism of the faders.1

History and Tradition

Martin E. Andresen and Martin Nielsen created the very first version of the Mixing Desk of Larp as a tool for teaching larp design at the first Larpwriter Summer School (LWSS). At the time, there was no coherent, unified model for understanding or teaching larp design. Although larp design had been debated, discussed, theorized about, and researched for years,2 comprehensive approaches to larp design did not exist.

Larpwriter Summer School is a weeklong course on larp design, organized by the NGO Fantasiforbundet (Norway) and Education Center “POST” (Belarus), and funded by the Norwegian government. It is aimed at participants who have had very little or no experience organizing larps. The course is taught by larp designers, pedagogues, and role-play professionals mostly from the Nordic countries (and later from Belarus). The first LWSS took place in 2012, and it has been organized annually since then. By 2016, the course had been attended by approximately 250 people from approximately 20 countries.

Before the first summer school, Andresen and Nielsen presented the Mixing Desk to the teachers. Each one were to take responsibility for a fader to present and teach to the students. In the planning session before the first LWSS and during the summer school the Mixing Desk was overhauled as the teachers, many of whom had designed, analysed, and published on larp design, went over it in detail. During the first LWSS each aspect of the Mixing Desk continued to be debated. The first iteration was published a year after the first LWSS.3 Work on the Mixing Desk has continued over the years, and it has been developed, fine-tuned, and contributed to by huge number of larpwrights, mainly at LWSS.4 One way to keep the faders fresh and to bring in diverse perspectives and improvement has been to assign different teachers to specific faders each year, enabling them to stand on the shoulders of previous speakers and adding their own perspectives. Andresen and Nielsen have remained central in the development of new iterations, acting as keepers of the Mixing Desk, although the framework now belongs to the community.

The Mixing Desk was not conceived in vacuum. There is a long history in relation to role-playing games and larp of enthusiastic players developing and debating emic theories of what role-playing is, what kind of players participate, how to design better experiences, and what is the best way to role-play. This history stretches back to not only the beginning of the publication of role-playing games with Dungeons & Dragons in 1974, but before that. Dungeons & Dragons emerged from the wargaming community, which already had a vibrant culture of newsletters.5 The theorizing has continued for decades, even if the discussion fora have changed (e.g. APAs, zines, magazines, newsgroups, web forums, blogs, books, social media).6 Some of the emic theories are very widely spread in role-player communities, influencing design, playing, and self-understanding. For example, much of the key terminology relating role-playing games (e.g. gamism, dramatism, simulationism, immersion) emerged from the discourses of the player communities.7 Indeed, even the term ‘role-playing game’ emerged from player discussions.8

As a model, the Mixing Desk is divided in two. First, the model is the idea that larp design can be broken down into faders. Second, there are specific faders that have been chosen as the content of the Mixing Desk. The content, as taught in LWSS, builds specifically on the tradition of Nordic larp.9 There is an international community of larpers and larp designers who come together at a the Knutepunkt conference, organized annually since 1997.10 An evolving tradition of larp design, playing, and thinking has emerged that has not only produced numerous role-playing games and larps, but also an annual English language publication of thinking on larp. The Nordic larp community gradually became more international over the years, as reflected in the LWSS. The community has produced quite a bit of thinking on larp and larp design, ranging from manifestos11 to challenges of auteurism,12 and from design analysis13 to doctoral dissertations.14 While a coherent design theory had not emerged prior to the Mixing Desk, there was a growing body of shared terminology, canon of key works, and a history of discourse on ‘hot’ topics. Many of the key figures in these discussions have been invited to teach at the summer school. The Mixing Desk, while shepherded by Andresen and Nielsen, is a joint effort by the community – and the joint production of the Mixing Desk forced people to critically examine their own theories in order to build some kind of a coherent whole. This work has, of course, fed back into the Knutepunkt tradition both through theory discussions and the larps designed by LWSS alumni.

Over the years, much of the terminology from the Knutepunkt tradition has crossed over to academia – even if the connected theoretical structures can be explicitly questioned. Role-playing studies continues to be a small field, and most of the scholars working in the area have a background as players. It would be foolish to ignore the knowledge and analytical tools amassed by the real experts of that field, the players and designers. Furthermore, game studies more generally has been open to contributions coming from game designers.15 In role-playing games and larps, where each gamemaster and larpwright has tremendous impact on the shape of the experience in which players participate, the line between an expert player and a designer is particularly blurry.

The Mixing Desk of larp is above all a design theory. We can contextualize it via game design theory in game studies. While larps are not strictly speaking just games,16 for example, they can be studied as games, and the long history of breaking games down into elements and identifying patterns in game design can be illuminating. Similar to the characteristics of games,17 the Mixing Desk has mostly been created by designers, and it emerged as a tool for teaching. Game design lenses18 are similar in the sense that they attempt to get the designer out of their comfort zone and consider new aspects of the design space. However, the ever-expanding game design patterns paradigm has much more affinity with this one, aiming for comprehensiveness and accuracy.19

Introduction to the Mixing Desk

Originally, the Mixing Desk was developed to serve three main purposes: to raise awareness of the spectrum of design opportunities inherent in larp, to help designers be more conscious of the design choices they make, and to help teach design vocabulary.20 Over the years, the Mixing Desk of Larp has developed into a formulation and a visualization of a design ideology, dressed up as an easily understandable metaphor. It is a thing-to-think-with for the larpwright to help map out the possible design space and to make design choices concrete.

In experience design, such as larp design, anything and everything from the temperature of the space to the costuming and from interaction codes to calorie intake, is a designable surface. The Mixing Desk seeks to visualize the most important considerations to take into account when making these choices in an approachable manner. Since the surfaces that can be designed will be present in a larp anyway, not making a conscious choice as a designer simply means leaving that choice to the participants, the tradition – or to happenstance.21 The Mixing Desk is driven by the idea that design is about making conscious choices. Understanding the design space and the surfaces available is important – as in understanding what options are available. Choosing one thing means that something else is left out.

The Mixing Desk is not just about designing the runtime of a larp, but inclusive of considerations of the lead up to the runtime and the debrief and post-larp period. A comprehensive design will consider not only the larp runtime experience, but the experience of participating in a larp in a wider sense. Thus, the events leading up to the runtime and the structured interactions following it are also designable surfaces, with important implications not only for the experience as a whole, but the community of larpers who are participating. Design choices become motivated by the kind of implications it will have on the player community.

The Mixing Desk aims to be a tool applicable to all kinds of larp around the world. However, dividing all possible designable surfaces into a dozen areas requires making choices. Thus, the thirteen faders taught at LWSS offer a very specific filter, expressive of a moment in time in primarily Nordic larp discourse.22 Another way to interpret the origin of the included faders is as a residue of what has been debated and developed in discussions and actual designs in Nordic larp in the last decade. The descriptions of the faders show bias as well; they are meant to be neutral, and they continue to be developed with that as an ideal, but the background and personal preferences of the developers show through nonetheless.

Even so, the Mixing Desk enables designers to see beyond their own tradition, and what lies beyond their ‘default fader positions’. These default positions are likely not questioned within small, homogenous larp traditions. However, when players and designers from different traditions meet, such differences in default positions are impactful, opening up possibilities for misunderstandings and disappointment when expectations do not align.23 For example, a larp need not be six hours long, the characters might be only able to communicate nonverbally, and all characters need not be written by the larpwright. The Mixing Desk has helped in developing shared vocabulary on larp design, enabling more nuanced discussion about larp design, and it has shifted discussion from ‘good’ and ‘bad’ design to the benefits and drawbacks of different design choices.

The philosophy behind the Mixing Desk of larp is more important than the descriptions of the faders. It is a-thing-to-think-with, and can be useful in analysing design, but it is not a quantitative metric. The Mixing Desk is not intended as a tool for discussing the outcome or the experience of the larp, but rather how it is composed. It does not support reducing larp design to numeric values on the scales (i.e., faders). In the event one would like to use the Mixing Desk to compare larps, it would at best be possible to do so on an ordinal scale of measurement. Indeed, the Mixing Desk is a metaphor. At times, the metaphor breaks down, however, since the choices being represented do not map onto the metaphor perfectly. Furthermore, since the goal of the model is to teach larp design to beginners, the Mixing Desk has prioritized legibility at the expense of precision.

Faders

The current Mixing Desk contains thirteen faders that can be independently “controlled.” Each fader has two ends, the so-called “minimum” and “maximum” positions. Both ends express design ideals. The faders are meant as descriptive, outlining the possible design space. Neither end is seen as better or worse on the level of description – although different local traditions obviously do value certain sets of choices more than others.

The two ends on the faders represent false dichotomies. The maximum and minimum positions are, purposefully, not each other’s logical opposites. For example, transparency and secrecy are in some ways oppositional, but not each other’s opposites. Both are active choices.24 For the same reason, the descriptions are also not meant to be comprehensive.

When discussing a larp, the faders encompass the aggregate design choices for the larp as a whole. Of course, different designable surfaces can have different design – for example, characters can be transparent while events are secret. Sometimes it will be useful for the designers of a larp to use the Mixing Desk approach to examine only a particular part of the larp.

The Mixing Desk is a pedagogical tool to help teach larp design and a design aid, a way to conceptualize design choices, and a specific filter to help sort out the endless design space into understandable chunks. The credo when creating the Mixing Desk has been to focus on clarity, not precision. Thus, in practice, the Mixing Desk is neither a complete, nor a completely coherent model. However, it does prove useful in practice.

Each of the thirteen faders covers a topic where design choices are needed. Both ends of the fader are expressive of design ideals; not choosing usually lands the design somewhere in the middle, depending on the larp tradition. However, one end does not necessarily exclude the other, albeit employing both ends requires some work. The larp need not be uniform in its design; it is possible for the faders to be in different positions in different parts of the same larp, and to design differing elements according to different design ideals.

While the faders are theoretically conceived of as being independent of each other, in practice choices relating to one fader can have important implications for another. For example, opting for secrecy in design usually implies that the organizers will handle responsibility relating to character or culture creation, or that they have an active runtime direction style. Furthermore, some of the faders can be locked due to external reasons: The venue may be set, the time available limited, or the budget fixed. Similarly, it may be possible that diverting too much from the local design traditions is difficult.

The choice of relevant faders, at least in theory, is independent of the Mixing Desk model. In the following, the thirteen faders that are currently covered at LWSS are described. Of course, other selections of faders are possible.

Openness: Secrecy and Transparency

The openness fader is about deciding how much the players know in advance about the larp in general and events during the larp specifically. Should they already know the genre and setting? What about plot twists and events? Should they have access to all the written material, or only what their characters might know? Should the players be encouraged to share information about their characters that they have made up themselves?

At the secrecy end the players only know what they absolutely need to know. This means that they do not need to wade through endless briefs looking for relevant information. In some ways, this means that the larp is beginner-friendly, as the amount of information needed to digest is manageable. The larp can be controlled, up to a point, through controlling the information. In some ways, larps that rely on secrecy are building on surprise; as characters uncover something new, the players are also surprised. Emotions like excitement and wonder may be stronger as a result leading to an overall stronger experience. One way to apply a very high level of secrecy is by the use of random events. If the outcome of an event is decided randomly, not even the organizers will know what will happen, and it will be impossible for the players to predict the outcome using meta-information about the larp.

On the other hand, surprises stop players from planning and steering their own larp;25 they cannot orchestrate their own experience if they do not know, even broadly, what the relevant elements are. This means that they cannot decide when to confront another character, when to push for more intensity, and when to ease up and give room for others. In addition, spontaneous reactions are not always the best. Can you really pretend to be brave when you do not feel brave in a context where you may be surprised at any moment? Surprises may also infuriate players, for example, if the genre of the larp shifts.26 In larps with a high degree of pressure on players, a high level of secrecy will create further pressure and increase the risk of player fatigue. Finally, surprises and secrets may never become known; if a character has a secret, they may keep that secret until the end of the larp.

Transparency is the opposite design ideal. In its pure form it means that each participant has all the information about the larp and thus enables control. For example, everyone knows all the darkest secrets of all the characters – not only what the organizers planned, but also all of the players own inventions – even run-time inventions (which are, of course, nearly impossible to transmit continuously). Transparency shifts focus from goals, such as finding out a secret, to process –– how that happens in an interesting way. Transparency helps players prepare better as they know what to expect. They can also shoulder more responsibility relating playing together and constructing a story, since they know all the moving parts.

The flipside is that too much information creates information overload. Passively making information available does not automatically translate to a high level of transparency. By facilitating the transmission of information actively through a workshop, the level of transparency increases. In such a workshop, the players can also share their own inventions. While sharing of information usually takes place before runtime, it can also happen all throughout the larp. Players can go out of play and share information. Larp mechanics that increase the transparency during play are called meta-techniques. Finally, radical transparency can be boring after a while, since the player already know everything ahead of time.

Both approaches require trust. Transparency requires that the larp designers trust the players to not abuse the power given to them over the overall design. For this reason, transparent design usually works best with larps designed for exploration as player motivation (see below). Secrecy requires that the players trust the larp designers’ judgement that they do not do anything too drastic or ill fitting by surprise.

Mechanics: Intrusive and Discreet

This fader is about determining how disruptive the mechanics the players use during runtime are. Disruptiveness can be understood as an aggregate estimate of how frequent the mechanics are, how much attention they attract, and how well they are aesthetically adept to the larp at hand. At one end of the spectrum the larp where players only carry out the exact same actions as their characters; at the other end we find larps that have explicit tools to shape the experience. Designers can give different kinds of tools to the players: rules (implicit and explicit), replacements (objects and actions standing in for other that are impossible or unwanted), and meta-techniques (formal techniques that play around with the linear, coherent larp fiction).

At the maximum end of the fader we find intrusive mechanics. They are used to start and stop play, for replacing actions or objects, and to consciously play with the character-player division. Intrusive mechanics often interrupt the flow of the larp either at a specific place or even in the whole larp. They are very visible, draw attention to themselves – and thus can be used to focus the playing – and are hard to ignore. Without intrusive mechanics, what happens in the larp is limited to what the players are organizers are able to carry out in the real world, and the players have no way of giving or receiving other input than the fiction itself during runtime.

On the other hand, intrusive mechanics disrupt the flow of the larp. They may not fit the fiction – and it can be impossible to opt out of them since they are so demanding of attention (for example, if someone ‘stops time’ in a whole room).

At the minimum end, there are the discreet mechanics. Ideally, a larp with discreet mechanism actually has no tools in use aside from starting and stopping (and safety precautions), but such a larp would have to be very naturalistic in setting and characters. Some mechanics are always needed, but they should feel natural to the story and fit the fiction. They should support immersion and engagement as they do not interrupt the flow. When successful, such mechanics are almost invisible and only address a few players. Discreet methods are easier to ignore and opt out of.

When methods are discreet, the seams of the experience are hidden. This means also means that there is less transparency, stepping out of character (within the mechanics) is harder, and safety issues may be harder to see.

Both the amount of mechanics in use and frequency of their use influence this fader, but also to which extent they are aesthetically adapted to the larp, and whether the mechanic can suspend play for many or all participants, or if it only applies for those who opt-in themselves.

Environment: 360° Illusion, Clarity, and Material Independence

The environment fader determines how similar the physical surroundings of the larp are to the fiction. Is the larp designed to be played in a fully realistic medieval castle, in an empty room with a few specific props, or in any random room? Although in practice environment design usually boils down to the visual and audible environment, environment includes everything the players can sense (e.g. scenography, sounds, temperature, smells, tastes). In this fader, the cheating by combining false dichotomies on the same continuum is particularly noticeable. This fader is actually two connected faders in one: The absence of non-fictional elements (“noise”), and the presence of fictional elements. The fader is best understood as the aggregate environmental impact of noise undermining the vision of the larp and fictional elements supporting the vision. Some larps focus on the physical surroundings or scenography to support the vision, while other larps introduce few or no elements of scenography. Simultaneously, some larps strive to remove unwanted elements or visual noise, while others place no requirements on this.

At one end of the fader there is the ideal of a 360° illusion, where there is high fidelity between the fictional location and how it is produced in the larp. There is no visual noise and everything looks and works in the real world just like would in the fiction. A (visually) coherent world is easy to understand, especially as everything is functional, useable, and playable. The environment feels real, encourages subtle and non-verbal activity, and looks very good in photographs afterwards. Often a 360° illusion requires access to a very specific environment; some environments are easier to find (a conference centre) than other (a medieval castle).

However, when everything is perfect, the player can feel out of place. They may feel that they are the one thing that is not perfect – or that their co-players are, as their familiar faces can be a reminder of the outside world. A 360° illusion also enforces real world behaviour as the players are only able to do the things they are physically able to do. Thus it can be less imaginative and less co-creative. Finally, setting up a picture perfect environment is potentially very expensive and labour-intensive, and playtesting ahead of time can be thus impossible.

Midway on the aggregate fader there lies the ideal of clarity – where both fictional and non-fictional elements are at a minimum. As in 360° illusion, there is minimal visual noise in the form of elements that do not fit the fiction, but there is also very limited amount of fictional elements. A black box larp with only a table, two chairs, a spotlight, some music, and a handwritten letter could be an example. Such a design has very sharp focus; only those elements that are necessary, are included. The environment is just as designed and curated as in 360°, it is just easier to start with a controlled, empty, black room and only bring key props. As the black box is a type of room that is found in theatres and other cultural space around the world, this design ideal is a solution to for designers who want a sharp design of the environment without compromising its ability to be re-run too much.

With limited scenography, the few items that are there usually attract more attention and acquire deep meaning. Playtesting remains important; even a minimalist larp can end up with messy levels of association with physical objects.

Finally, there is the ideal of material independence. Here, it does not matter what the environment is like. There can be all kinds of noise and only very few fictional elements represented with specific props. The emphasis is on the ease of staging: a pure example of materially independent larp would actually be tabletop role-playing. Such role-playing can be conducted anywhere since the surroundings –– outside a table and chairs –– do not matter to the design. This is great for shorter scenarios and convention larps, as the staging is easy. It also encourages verbal (and social) interaction, as the collective fiction does not rest on the environment, but the players actions. Thus, it requires more from the players, but when successful, it brings focus.

On the flipside, a coherent world is harder to sustain with larger groups and longer larps if everyone needs to imagine everything. Similarly, nuanced non-verbal actions are hard to signal when they are happening without props or environment. In addition, materially independent larps just do not look as impressive.

Using one’s environment actively can add significantly to the experience of the larp, but strict requirements on the play environment also mean that it will be harder to find a venue for the larp. Designing for material independence means finding a venue is easier and there is less hassle with props and costumes.

Character Creation Responsibility: Player and Organizer

Not all the fader ends reflect unique design ideals. For example, this fader and the two that follow are quite similar. These three faders are about dividing the power and the labour between the players and the designer. The competing design ideals in this trio of faders are the ideal of using larp to bring to life a curated and controlled designer vision, and the ideal of egalitarian co-creation.

This fader is about deciding how the character creation responsibility is distributed. Do the designers create very specific briefs about each character, or do they just provide the players with the tool or the inspiration to create their characters? Of course, ‘a character’ can take make forms. It can be a written description, a character sheet with skills, attributes, and special abilities, or something more symbolic or lyrical like an image or a song. However, usually a character includes the background of a persona, as well as their goals, dreams and fears, most important relations, available special actions, and the functions they perform (such as baker, assassin, and father). When players create their characters, they usually do so for a sandbox setting, by following a specific rule system and often with a set number of points. When the larpwrights create characters, in many traditions they are usually presented at least in a written format, as a brief life story. There are also numerous traditions where the character is created through some collaboration between the larpwright, the players, and possibly other players as well. For example, groups of players can create character groups based on designer’s brief, a player can fleshes out a character based on a sketch by a larpwright, or a whole player group can create their characters in a tightly organizer-facilitated workshop prior to the larp.

When the characters are created by the organizers, the most obvious benefit is control. The designers have a full picture of all characters and how they relate to each other. They can be sure of the consistency of story, of quality, of vision. This also enables them to achieve any kind of a balance between different characters of groups. When characters are created by the organizers, the players have a stronger alibi27 to play in deviant ways: After all, the player did not dream up the character. Organizers can also consciously create characters that counter stereotypes and genre tropes.

On the other hand, creating each character fully is very time consuming. Not only need everything be created, checking the interlinking between characters is a big task. Conveying the complexity of relations is also difficult with words. When players have little influence over the character and its relationships, it will be necessary to invest more time in the methodology for conveying the relations and calibrating the understanding of them among the players. Finally, the downside of having control over this part is that it disregards player creativity and participation.

When the responsibility for creating characters rests with the players the size of the larp can easily be scaled up or down. Once the process for character creations is set up, quantity of characters need not be an issue. Players will have more ideas and –– as they have created their own characters –– stronger ownership and connection with their creations. Yet if the players lack experience with larp design, they might easily end up creating characters that lack playability unless skilfully guided.

Yet, when the organizers only set the frames for character creation, they lose all control over what the characters are like. The genre and setting need to be clearly articulated to ensure that the characters fit the same world. Popular tropes often manifest, usually calibration amongst the players is still needed,28 and connections between characters need to be set up (or a process for setting them up should be created).

A larpwright can combine the two methods, for example, by facilitating the players’ character creation. Such a process is great for when aiming for coherence and specific theme and setting while harnessing player creativity for new ideas and increased ownership. For example, characters can be created in a facilitated workshop. A good facilitator can help the players thinking out-of-the-box. Furthermore, the workshops are time-consuming for the players, although it can save the organizers time. Finally, even though character creation is guided, some designers may still feel that there is not enough control.

Culture Creation Responsiblity: Player and Organizer

This fader is about determining how the responsibility for creating the culture is divided. This fader is very similar to the previous one, and many of the issues that should be considered are the same. The basic question is if the culture should be organizer-created or player-workshopped. Culture is here seen as meaning the interaction patterns, norms, values, customs, beliefs, laws, and morals of the character groups.

If the fader is at the extreme end at “organizer,” then, as with the previous fader, the most important benefit is control. The organizers can assure consistency of vision, quality of the content, and can prevent defaulting to well-known patterns. Such patterns are less interesting to play, and can even be exclusionary (e.g., unintended misogynist, racist, homophobic). When the organizers are in control, they can avoid any such unwanted patterns, but also make sure that they are present when that is the subject at hand (e.g. a larp dealing with prejudice might deliberately apply a culture full of prejudice). Organizer-created culture is particularly fitting for educational larps, where the fidelity of the simulation is important. But, again, this disregards player creativity, and results in less ownership. A culture created by just a few people can also end up monotonous.

At the other end of the fader there is culture created by players, usually in a workshop. The obvious benefit is that the players know the culture intimately and own it. There can be creative bliss when brainstorming a culture – and a culture created by a host of people can be more diverse. When creating culture in a workshop, it allows the calibration of the cultural understanding to be integrated into the creation process, while an organizer-created culture will need separate calibration exercises. However, often a joint workshop yields the most obvious of ideas, especially in the beginning. The players, especially if unexperienced, will need guidance when creating a culture to ensure that the culture fits the overall vision of the larp (i.e., is plausible), that it is interesting, playable, and safe – and that it is sustainable in the sense that the playability of the culture does not wear off during the larp.

Of course, even if the responsibility lies with the organizers, they need not create a culture. They can simply curate it. They can choose an existing larp setting and system (such as Vampire: The Masquerade) or adopt a well-known fictional world, such as Harry Potter or Firefly. It is even possible to do mash-up (such as combining Hamlet and Sons of Anarchy). Even when the culture and setting comes pre-packaged, some translation and adapting is still needed, as well as calibration among the players.

Finally, even if the organizers create the culture completely, as runtime begins, the players will take it over. Players will always improvise stuff, and most likely they will tend to fill gaps in the culture by bringing element of their own culture. The organizers only ever create the starting point for the players.

Runtime Direction: Active and Passive

This fader accounts for how much the larp organizers influence the larp during runtime. For some organizers and designers, the work is done when a larp starts, while for other the active shaping of the actions during runtime is a key part of the design.

An active runtime direction style means that the organizers keep control of the larp at all times. They can, for example, control the pacing, bring focus, drive the plot, and adjust challenge to fit individual players. This design choice is common for scenarios following a set story where the players generally only influence how things happen, not what will happen. Having someone clearly in change can add to feeling of safety for the players.

The challenge is that if runtime direction is too active –– too railroaded –– then the players lose agency. The organizers becomes the centre of attention. The larp is more about them and their vision than anything else. Player involvement and immersion are at risk.

A passive style basically means handing the larp over to the players when it starts. The players have a high level of freedom to play in the sandbox of the larp. This enhances involvement, immersion, and ownership. Beforehand it is impossible to predict how the larp will develop – which can be a positive or a negative result.

Most larps are somewhere between the extreme ends. Runtime direction can take many different forms. There are discrete ones, like adjusting the mood through changes in lighting and music, guiding play through instructed players, having planned events, and introducing new characters halfway through. The more intrusive ones interfere with the play more directly, such as stopping the larp and instructing the players to do a scene again differently, doing time jumps, or swapping characters.29 When the players do these things, they are called meta-techniques; when the organizers do it, it is active runtime direction.

Since very active direction is disruptive, it is common to delimit it to a specific area. This area, a meta room, is set aside at the larp location for the purpose of playing flashbacks, dreams, and anything that cannot happen in the main timeline of the larp. The players choose to go there to have strongly directed scenes often set by an organizer.

Loyalty to the World: Playability and Plausibility

This fader addresses the level of simulation that the larp is trying to achieve. In any simulation choices need to be made as to what is represented and how. The ends on this fader are plausibility (the world of the larp should be simulated as well as possible) and playability (the larp should run as smoothly as possible). These ideals can be in conflict; sometimes what is best for playing makes no sense within the fiction.

For example, it might be plausible that female characters in some historical settings have less agency, but it might not be very playable for contemporary players. Portraying a military hierarchy in a realistic fashion can also strip many characters of agency. On the other hand, if exploring a specific world or situation is key to the larp, then removing important aspects of that, even if they are boring to play, would detract from that central goal.

The fictional world of the larp can simulate (an aspect of) the real world, simulate an existing fictional world, or it can be built from scratch. In larp worlds based on existing worlds, the players will have a notion of what is plausible. When a new world is created, nothing is implausible at the beginning. However, as the world is built up, a ‘fictional realism’ and plausibility of that world is established. However, just as with characters, players tend to fill the gaps in the world with their understanding of the real world and of genre fiction.

If the fader is set all the way to maximum on loyalty to world, there is plausibility. The larp world is coherent and makes sense. There is a sense of believability and (contextual) realism. Plausibility is associated with such ideals as authenticity, realism, and immediacy.

Plausibility can be difficult to maintain. A simulation is always a simplification –– otherwise it is not a simulation, but the real thing –– which means that plausibility cannot be complete either. Plausibility also places tight restrictions on the overall larp design – and it can lead to boring play.

At the other end of the fader there is playability, boring play can be removed and all kinds of fun possibilities can be implemented. It is also easier to be surprising and break stereotypes, when fidelity to the world being simulated is not a requirement.

On the other hand, deviating from simulative relationship with the world being portrayed can make the larp harder to understand. The coherence of the world suffers when the realistic and effects of certain causes no longer automatically follow, just because they are boring or otherwise unattractive to the players.

Pressure on Players: Hardcore and Pretence

If the larp invites the players into situations where their physical or social comfort will be challenged, then there is pressure placed on the players. This fader visualizes how much pressure there is. Two questions help positioning this fader: Does the larp tackle challenging issues from the real world? How close is the player experience to the character experience when things are hard?

If the larp addresses real world issues, perhaps even difficult personal issues, this increases the pressure on players.30 The pressure can, however, be modified by replacement mechanics. An example would be substituting a metal swords with boffers or sex with a backrub. Indeed, the most obvious examples of this are violence, drugs, and sex, but the list also includes bullying, racism, loss, shame, grief, oppression, self-doubt, and pressure to perform. When replacement mechanics are applied, the level of pressure is mostly determined by the nature of the replacement mechanic. For example, if beating someone down is replaced by firmly pushing someone to the ground, there is still a certain amount of pressure in the replacement mechanic. If the replacement mechanic for beating someone is clapping your hands, the pressure is low.

Pressure also rises, if the players are not given protection against dealing with these issues; for example, thin characters and weak alibi add pressure. So does uncertainty about what will happen next.

Playing around with creature comforts without replacements –– e.g. hunger, sleep deprivation, exposure to the elements –– can also up the ante. Finally, player agency is also relevant for this fader: if players can calibrate their characters, opt out of certain tasks, actions, or parts of the larp, the pressure is lowered.

At one end of the fader there is hardcore. When the pressure is high, the players’ experience is visceral, it engages all senses intensely, and it is thoroughly embodied. The separation between experiences of the player and the character is thin – and feels more authentic. Hardcore also allows for nuance in engagement with hard topics, as there is less simulation. It is also visually clear; scenes are legible and easier to engage with also from afar.

On the minus side, severe pressure undermines the player ability to role-play, and be playful; it is serious and requires commitment. The experience may not actually be that authentic either, and it can seem like slumming or grief tourism. Hardcore design also can encourage risky behavior, especially if it is combined with peer pressure. This is particularly destructive, if the design contributes to the idea that being able to withstand intense play is “cool”.

Hardcore pressure may also push players to steer away from the difficult content; without simulation they may not want to engage with certain activities. For example, in a larp without replacement mechanic for fighting, the threshold for violence is much higher than in a larp with latex swords. While reducing the likelihood or frequency of a high-pressure action, the pressure would be higher should a fight still occur.

If the a key goal of the design is to have many people experience a particular action, the designers need to consider the combined effect of the pressure and the frequency in which people will opt in to experience it.

Playing with high pressure places an extra responsibility on the organizers to make sure the players have actively opted in on what they are going to experience.At the other end of the fader there is pretence. The players now only pretend to do the actions that they are signalling, and there is less fidelity in relation to the world around the larp. Pretence is about role-playing, not about an extreme sport. There is much more playability as actions and stories are available for all players. A player does not need to be able to do acrobatics to play a circus performer. Power is also distributed differently, as endurance, steadfastness, strength, and control are not the most important base requirements. Indeed, consequences of the larp can be ignored. Where hardcore is uncomfortable and intense, pretence is safe and playful.

However, the playing does not feel as real as there are no consequences. Lacking viscerality, the players may only access the larp on an intellectual level. Also, the participants need to learn the replacement mechanics and other rules – and they do focus the larp somewhat. Whatever you have rules for, that is what the players will do.

This fader moves easily by accident, either through incompetence or bad luck. Logistical failures, hostile weather, bad safety or calibration systems, unreliable people, and weird drama amongst the participants all tend to add to the pressure. Such things may be difficult to predict, but they can be prepared for.

Player Motivation: Victory and Exploration

What is the driving motivation of the players to take actions inside your larp? This fader tackles what is known as the pre-lusory goal, the state of affairs a player wants to reach while playing.31 Are player playing to win, do they want to explore the setting, the characters, or the world – or do they have some other goal in participating in this larp? While design of the fiction is important for the level of competition in a larp, the key criterion for this fader is whether the players are encouraged to strive to achieve the goals of their characters.32

Some larps are competitive and game-like. There are clear goals and objectives for each character. Usually there are also finite resources; all players cannot reach their goals at the same time (i.e., the larp is a zero-sum game). In these larps, there will be a high level of competitiveness when the players are encouraged to strive to reach their characters’ goals.

This ideal is called victory. Extreme game-like larps can be won. Game-like larps tend to make available actions very clear. They are also beginner friendly for people who have a background in games or are competitive.

Competition is a great motivator – at least for some people.33 Competition leads also to disappointment and disagreements. Haggling over rules can distract from the playing of the larp, especially if the larp becomes all about winning. One cannot have winners without losers, and with highly competitive larps, cheating may be a real problem.

At the other end of the fader there is exploration. Collaboration can take the place of competition. The focus is now on the experience, the world, the themes, the system, and the characters, and not on winning –– and egos. A satisfying story is a goal in itself. Failing at achieving your character’s goals is not losing; it is a tragedy. Note that it is possible for characters to compete in a larp that values exploration –– as long as the winning is not the driving goal for the players.

Exploration requires something to be unknown. Since role-play is often character driven, that unknown is often present in the form of some ‘other’ or some unknown experience. Exploration tends to associate more with collaboration and thus building trust is important. When successful, this creates a foundation for strong stories and creates room for sincerity. At the same time, it removes risk –– and the excitement that risk brings.

A common design is a middle position on this fader. The players are encouraged to try to reach their characters’ goals – or at least not discouraged from it – but there are also worlds, stories, and characters to explore. The players chose themselves whether to play competitively or not. If the organizers does not make sure the players calibrate their playing style, it can lead to conflict and ruin the experience.

This fader was earlier called “Story Engine” and end points were competition and collaboration. The difference in emphasis with that was either playing to win or playing to lose. Playing to lose is Nordic shorthand for playing for maximal drama, which sometimes means that you should have your character fail, to be defeated, or to allow your characters secrets to leak out.

Character as Mask: Differentiation and Thin Characters

This fader is about the distance between the player and the character. Is the character completely different from the player, something alien they do their best to portray? Or, is the character identical to the player, do they play the character as if they themselves were transported into a fantasy world? Obviously, a big part of this is up to the player to determine. However, it is also a design decision. As a designer, do you use elements from the players’ real lives in the larp, or do you deliberately try to maximize the distance between the character and player?

The player and the character can be similar or different in many ways. First, there is the body of the character. Do the player and the character share the same ethnicity, skin tone, height, weight, shape, ability, voice, gender, sexuality, and age? Second, personality and experience come into play. How alike are personal history, name, education, love life, traumas, phobias, financial situation, religion, values, and goals with that of the player? Third, how similar are the social roles, such as occupation and class, of the player and character?

Having a clear differentiation between the player and the character is for many people the heart of role-playing, acting ‘as if’ someone else, walking in their shoes and seeing experiencing the world through someone else’s eyes. It supports escapism, and taking a vacation from your everyday self. Emphasis is on empathy. Furthermore, clear differentiation gives the player a stronger alibi during play. They can explain their actions as arising from that character. Larps with clear differentiation are also easier to cast since there is no need to find players who are similar to the characters created.

The downside is that if the characters are clearly different from the players, then there is more work, since those differentiated characters need to be created. For players, it is probably harder to play characters that are different from them, creating possible believability issues. In the end, total differentiation is an illusion.

Having thin characters, which is also referred to as “playing close to home,” is the opposite strategy. Here the idea is to use the players’ personal experiences or background to create a strong emotional experience. Thin characters can be a useful way to shift focus from the character to situation. For example, if you want privileged school children to experience what it is like to be a refugee, you can create characters that are similar to the players in all aspects except that they are refugees. Of course, thin characters also work very well as power fantasies: If a player wants to try out what it would be like to be a charismatic superhero.

Thin characters are more ‘complete’; since the player’s life up until now is what the character is based on, the characters are complex and believable. However, the alibi to play will be weaker, when actions are seen as arising more from the player than the character. If many larps use thin characters, that can lead to players being typecast.

Strong emotions can be created either way. When using clear differentiation the aim is to help the player experience the world from a different point of view. Design with thin characters replicates and amplifies the players own emotions by removing some of the protective shield of the character. It brings the larp closer to reality, or ‘transports’ the player to a strange place (i.e. lets the player play themselves in a fantastic situation).

When the emotions or opinions of the player affect the character it is often termed bleed-in (indeed, this fader was originally called the bleed-in fader). When the character’s emotions or opinions affect the player, it is referred to as bleed-out.34 Accidental bleed from player to character happens when the character is similar to the player without it being designed on purpose.

It is possible to create thicker characters that deliberately are close to the player on specific areas. For example to bring in elements from the players’ love life in the love life of the character (while the character in other aspects is very different from the player). Such design requires the organizers to have knowledge of the players’ backgrounds, or to design workshop techniques to extract such knowledge and enter it into the character creation. This approach makes the character look thick at first glance. However, as long as the “thin spots” are designed to fit the subject of the larp, this will for most of the time have the same consequence as thin characters.

Communication Style: Verbal and Physical

People can communicate in many ways. What kinds of communication styles does a larp design encourage? Co-located humans tend to communicate through both verbal and body language. Both can be encouraged, discouraged, and shaped through design.

Verbal communications is more precise than just using body language. It encourages very clear signaling, and leads to fewer misunderstandings (if the players have sufficient language skills). If a harmonious understanding of the fiction amongst players is valued, verbal communication is a very useful tool. However, emphasizing or allowing only verbal communication limits other communication forms, and limits emotional engagement. It is easier to stay detached when only words are used. In addition, a shared language is obviously required amongst the players. An extreme emphasis on verbal communications would be a tabletop role-playing game, where even hand gestures are uncommon.

Physical communication, for example through body language and touching, fosters a stronger emotional connection between players and can be more playful. There is a strong emphasis on embodiment. However, physical communication is much more imprecise. Larps that emphasize physical communications may even do away with a shared fiction, and work in a more metaphoric way. A shared spoken language is not needed, although also the meaning of specific physical interaction is culturally tied. An extreme example is a larp where language does not exist.

Most larps use both language and body language. Words are spoken, hands shaken, and shoulders shrugged. Yet both kinds of communication styles can be developed and designed. Specific terms and phrases often have special meaning in a larp. Similarly, glances, movements, patterns of touching can be imbued with specific meaning, although this usually requires workshopping before runtime to ensure that players have an equifinal enough understanding.

Representation of Theme: Stories and Actions

This fader asks the question: How is the theme of the larp represented and actualized during runtime? Do the organizers have a story in mind that will prompt the actions? Or does the design focus on embodiment, actions, and movements of the players, in order for the players to co-creatively enact the theme?

The theme of a larp is its topic, subject, or core question. A theme is not the same as genre or setting, although certain genres or settings have stereotypical themes they often address. Larps do not need explicit themes, but if one is not consciously picked out by the designers, one may very well emerge during play. Of course, it is possible for the players to hijack the theme of a larp –– for example, a larp about oppression could become a larp about the rise of democracy –– but that is harder when there is a clear theme to begin with. A central theme brings about coherence; when a larp is clearly about something, it is easier to design for it and play with it. The larpwright can attempt to enact the theme of the larp through designing stories, but also through designing actions.

At one end of the fader we find stories. Now, life is not a story, and neither is a larp. Both feature things happening one after another, and afterwards they are narrativized by the players. These events are turned into a story. In practice in larps, a story is how and why our fictional characters interact. A designer may focus the design on the background stories of the characters, the world of the fiction, and scripts for events to happen in the larp, but leave it to the players to figure out the actions.

At the other end, there are actions. They are in the moment; an action is the process of doing something. Of course, once an action is connected to a doer, or a reason to act, a story starts to emerge. The designers of a larp can focus on instructing, nudging, or encouraging the players to take certain actions. With this approach, the theme will be enacted. Stories may emerge in the minds of the players, and possibly a common understanding of a story emerges among the players. A larp that is close to the extreme action end of the fader gives the players solely input on actions to be taken.

Obviously, larps feature both stories and actions. This fader addresses the distribution of input from the organizers to the players. Are the players given stories as input to figure out the actions, or actions that will prompt them to make up a story? This is traditionally the hardest fader to grasp, perhaps because larps driven by actions (dance, movements, gestures) are uncommon, and often seen as overly artsy. Perhaps it is helpful to compare this fader to the previous one. That one maps verbal and physical communication, but since that fader emphasises communication, it tends to alight more with story than action. In this fader the action end can be thought of having actions for their own sake.

Stories are intellectual. The mind sorts the events into a sequence and assigns meaning to it. They are easy to verbalize, which means a shared understanding is easier to produce and generally emphasising stories requires very little workshopping. They are both beginner friendly and adult friendly – because they are less playful. Also, larp stories also tend not to be fully coherent, but they are coherent enough.

Actions are embodied. They are associative; there is a logic of their own in them. Emphasising actions obviously creates a stronger alibi for physical interaction. Emphasising actions is playful, and kid friendly. There is no requirement that things need to make sense. Thus, there is more room for personal interpretation. Building a theme from actions requires workshopping, and it may still be hard to understand the meaning of. If successful, it can re-encode behaviour, and stays in the body for a longer time. It is not so much rational as lyrical.

Your Faders Here

There are twelve set faders on the Mixing Desk used for teaching at the Larpwriter Summer School. The last one is marked “Your Fader Here” in all of the iterations. In some ways this faders is the most important as it clearly communicates that the twelve faders do not capture the whole of larp design. Anyone using the Mixing Desk is encouraged to add their own faders, ones that can help them understand their design practice better and helps them see new design opportunities, as well as remove faders that does not make sense to their particular larp design process.

Originally, there were only eleven faders used at the Larpwriter Summer School. One has been added since then, namely the culture creation responsibility fader. Numerous new faders have been discussed over the years. These ones have come up in LWSS over the last few years:

Technology dependence fader would account for the amount of technology need to make the larp (and its props) work. That fader would stretch from ubiquitous to simple. Larps with ubiquitous technology have automated what they can and sufficiently well-crafted technology is indistinguishable from magic. A simple larp would be easy to set up and move (“fits in a plastic bag”) does not require fancy gadgets, software updates, specific equipment, let alone unique prototypes. This fader has been suggested numerous times by Russian larpers since technology, and how it is handled, is particularly important in some of their larp traditions.

In France, the Mixing Desk is sometimes used when describing upcoming larps. In the French version35 there is an additional story fader that places experiencing a day in the life (simulationism) and experiencing a story (narrativism) at each end.

Indeed, the new fader proposals tend to be tied to the discourses that are going on in the larp scene. For example, the proposed stimulation fader, which accounts for how much the design prompts the players during runtime, is clearly tied to the discussion on brute force design.36 The fader would run from serene (no stimulation, possibly boring) to abundance (brute force design). Similarly, the discussion on labour at larp led to talk about a fader on character function.37 Does the character mainly exist as a role (e.g. guard, warrior, butler, wife, priest), or as a fully realized persona, with wants and need outside the roles they perform?

Finally, there is a group of proposed metafaders that describe the choices and motivations that underlie the concrete design choices. These metafaders are useful when comparing educational larps, long running campaigns, and thematic one-shots, but they fit better on a Mixing Desk of Organizer Motivations than a Mixing Desk of Larp. For example, there is the organizer motivation fader. At one end, there is the larp as the expression of the designer’s vision. Anything and everything is in the service of expressing this.38 Midway on the fader there is community vision, i.e. coming together to co-create something. At the other end there is customer service; the designer is creating a larp for a customer based on their specifications. Another metafader that has been proposed is political purpose. It would run from outright revolution to playfulness. Alternatively, perhaps, from social justice to separatism. Different variations have been discussed.

As discussed above, a fader can be in different positions in different parts of a larp and different designable surfaces in a larp can be approached according to different design ideals. Alternatively, a team of designers using the Mixing Desk in their creative process can split faders, and the design domains they represent, into smaller pieces. For example, a larp can apply transparency through meta-techniques but not through sharing character background before the larp starts. A design team wanting to use the Mixing Desk as a tool to discuss these design choices could apply a mechanics transparency fader and a pre-larp character transparency fader.

The twelve faders used by the Larpwriter Summer School represent one way to divide the design space of larp. They are a starting-point for thinking about larp, not an exhaustive statement. Indeed, the metaphoric form and the underlying philosophy of the Mixing Desk are more important than any specific fader.

In addition to alternative faders, there are examples of the entire model inspiring applications of the metaphor in other fields. For example, Anni Tolvanen made a Mixing Desk of sound design and Ingrid Galadriel Aune Nilsen has made a Mixing Desk of museum communication.39

Discussion

The end positions of the twelve faders are all tied to design ideals. As ideals, they are unachievable. Actual larps always exist somewhere between the ends, combining elements in an interesting fashion, and balancing not only the many ideals, but trying to protect those ideals in the harsh conditions of the reality of larp organizing. The Mixing Desk helps in visualizing those choices, which hopefully also helps in communicating them to the prospective players.

The faders have evolved quite a bit since they were first introduced – and still continue to do so. Even if the terminology would not have changed, the interpretation has. In the development of the Mixing Desk, discussion has helped it evolve, but more importantly new larps have been designed that have questioned or solidified the wisdom expressed in the Mixing Desk.

For example, there used to be a fader called scenography. The name was changed, as the term is very tied to theatre. Words are particularly important, as the Mixing Desk is a teaching and heuristic tool. The terms chosen are hopefully understandable and precise. References to other domains, such as theatre and games, are particularly thorny, as they are easily understood, yet they often have the wrong emphasis, or underlying power structure. The scenography fader is now known as the “environment” fader. Larps’ sites are not just a visual backdrop, but full environments where most things can be touched and used. Environment is thus more specific and accurate, while still being understandable.

Furthermore, the environment fader originally went from 360° illusion to minimalism, reflecting the strongest design ideals in Nordic larp at the time. Over the years, minimalism has morphed into clarity, as that is a more specific (and less limiting). In addition, material independence was added as a third ideal to account for all the convention larps being run –– and to underline that choosing to place very little focus on the environment is also a valid design choice with clear and concrete benefits.

Many of the faders also seem to cover similar questions, just from slightly different angles. Thus, most design choices will affect multiple faders simultaneously. This is the nature of larp itself. The Mixing Desk attempts to render the design questions specific to larp visible. In the final analysis, the Mixing Desk could be boiled down to two key dichotomies, two tensions that drive all larp design.

Foremost for the larpwright, player creativity is the negative space of larp design. Everything else is put in by the designer, yet without that negative space, there is nothing to see. Larp, as a form, is co-creative. The larpwright can do much with design, but in the end, the players must have agency over their experience. Finding the right balance between control and freedom, collaboration and leadership, design and improvisation is challenging in every larp. Indeed, this division of labour is at the heart of larp design. This is the reason why so many of the faders aim to make sense of the numerous choices in being organizer-lead or player-driven.

The second key aspect is the negotiation between, on the one hand, naturalism, plausibility, immediacy, and authenticity, and, on the other, structure, curation, predictability, and artificiality. The larp experience should be as real as possible – without having the drawbacks of reality, such as being boring for long stretches of time, being very exclusionary based on skills and appearance, and being not only dangerous but often devoid of meaning. Indeed, it is important to remember that realism is an “-ism.” It is an artistic movement dating back to the 19th century. Similarly, simulation is never complete, or it stops being a simulation. This is the other balance that many of the faders help striking, the balance between wanting to be real and wanting to be meaningful.

Conclusions

The Mixing Desk has served as a teaching tool at the Larpwriter Summer School five times, and each year the faders have been iterated and the philosophy behind the model sharpened. Writing down a detailed account of the Mixing Desk implies that it has reached maturity. A consensus about the form of The Mixing Desk appears to have been reached, and adjustments at this point are minor. They are more about fine-tuning and updating, than overhauling and rethinking. Yet this account of the model is not meant as final, but as a snapshot. While the form of the Mixing Desk may not need overhauling very often, the contents should be reviewed regularly to keep up with the discourse. This constant updating also hopefully prevents the model from turning into a dogma. The Mixing Desk is a thing-to-think-with, a tool for the designer. As a tool, it fits certain jobs better than others.

The Mixing Desk was created to help raise grasp the design space of larps, to empower designers to be more aware of their choices and default positions, and to contribute to the development of larp design vocabulary. As a design theory, it has proven to be useful both in practice and in analysis.

Acknowledgements

First, the authors would like to thank everyone, who has participated in organizing the Larpwriter Summer School over the years: Erlend Sand Bruer, Aliaksandra Franskevich, Alexander Karalevich, Tatsiana Smaliak, Åslaug Ullerud, and Aliona Velichko. Second, the authors wish to thank all who have contributed to the Mixing Desk over the years. In the beginning Teresa Axner, Anna-Karin Lindner, Miriam Lundqvist, and Lars Nerback were especially helpful. Since then the Mixing Desk has been contributed to at least by Erik Aarebrot, Carolina Dahlberg, Tor Kjetil Edland, Nina Runa Essendrop, Eirik Fatland, Tova Gerge, Pavel Hamřík, Erlend Eidsem Hansen, Mads Havshøj, Signe Hertel, Jana Hřebecká, Masha Karachun, Yauheni Karachun, Petter Karlsson, Johanna Koljonen, Trine Lise Lindahl, Karete Jacobsen Meland, Magnar Grønvik Müller, Charles Bo Nielsen, Åke Nolemo, Oliver Nøglebæk, Bjarke Pedersen, Juhana Petterson, Maria Raczynska, Olga Rudak, Nastassia Sinitsina, Grethe Sofie Bulterud Strand, Kristoffer Thurøe, Anni Tolvanen, Eliot Wislander, Gabriel Widing, and everyone else who has taught at the Larpwriter Summer School. Finally, the authors would like to thank Johannes Axner, Thomas B, Anne Morgen Mark, and Evan Torner.

—-

Featured image by Petter Karlsson.

—–

Jaakko Stenros, PhD is a game and play researcher at the Game Research Lab (University of Tampere). He has published five books and over 50 articles and reports and has taught game studies and Internet studies for almost a decade. He is currently working on understanding and documenting adult play and uncovering the aesthetics of social play, but his research interests include norm-defying play, role-playing games, pervasive games, and playfulness. He has also collaborated with artists and designers to create ludic experiences. He lives in Helsinki, Finland.

Martin Eckhoff Andresen plays and organizes larps and larp-related

projects based in Oslo, Norway. Among the projects he has been

involved in are: Grenselandet – Oslo International Chamber Larp

festival, Knutepunkt, the Belarusian Larpwriter Challenge and the

Larpwriter Summer School. In another life, he’s a PhD student in

Economics.

Martin Nielsen is a larp designer and event organizer from Oslo Norway. He has been a key contributor to Fantasiforbundet’s projects in Lebanon, Belarus, and Palestine as well as meeting places such as Grenselandet and Knutepunkt in addition to The Larpwriter Summer School. As his dayjob, he is the manager of Alibier AS, a company making educational larps.

2 thoughts on “The Mixing Desk of Larp: History and Current State of a Design Theory”

Comments are closed.