Brazil faces a great educational challenge – students, teachers, parents and employers are unhappy with how the country´s current educational system works and its outcomes. Yet the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) of Brazilian students’ reading, mathematics, and science scores yielded disappointing-yet-optimistic results:

While Brazil performs below the OECD average, its mean performance in mathematics has improved since 2003 from 356 to 391 score points, making Brazil the country with the largest performance gains since 2003. Significant improvements are also found in reading and science. […] Brazil performs below the average in mathematics (ranks between 57 and 60), reading (ranks between 54 and 56) and science (ranks between 57 and 60) among the 65 countries and economies that participated in the 2012 PISA assessment of 15-year-olds.1

Educator Jose Pacheco points out one possible underlying cause: Brazil insists on using 19th educational paradigms and 20th century teachers to teach 21st century students2. Simply adding new electronic or online technologies will not solve the problem if these are planned and implemented in the old paradigm.

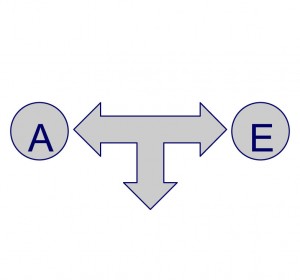

Another problem found in different levels of education is that many students do not show the level of autonomy that is expected of them. We understand autonomy as proposed by Gui Bonsiepe: a key element of democracy – the possibility to create a space of participation and self-determination for anyone. A space for individual projects of one´s own design. The opposite is heteronomy, or subordination to an order imposed by external agents, be that a dictatorship or the media.3

Educators continue to ask us to create didactic situations that stimulate students to develop autonomy and teamwork skills. At the moment, our educational system reduces these competencies, instead promoting an individualist heteronomy that reduces our students’ creativity and critical thinking. Sir Ken Robinson has notably criticized the factory line educational model that produces this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zDZFcDGpL4U

Role-playing games (RPGs) provide a way to develop autonomy and teamwork skills by our students due to their nature: a cooperative storytelling environment in which a player interprets one of the protagonists of the story being told and actually decides, within the rules of the game, what his or her character does. But how should we run tabletop RPGs, our specialty, in classrooms that have from 20 to 40 students? What if it is not possible to ask other students to be the Game Master (GM) for other students? Below is a discussion of our two attempts.

Didactic Ludonarrative

Didactic ludonarrative is a method to create a narrative game in which a player will experience a story and create a character, a plot, a setting or even a whole new story. This creative experience mobilizes competencies and existing knowledge from the participant through narrative gaming, desire and fantasy, and allows this person to build new competencies and knowledge.

Although we are aware of the use of the term “ludonarrative” in the videogame industry, and its variations, ludonarrative dissonance, ludonarrative cohesion and resonance, and ludonarrative alienation, through published gamer articles,4 we came to the term through our own work with educational applications of tabletop RPGs.

Currently, didactic ludonarrative consists in experiencing/playing a participatory story that happens in a setting chosen by the participants to achieve learning goals through (1) the expression of and/or solution of project problems5 and/or (2) the development of a setting by the participant.6

The didactic aspect of our method is based on the constructivist perspective of the Brazilian educators Paulo Freire and Carmen Moreira Neves, Fernando Hernández´ project pedagogy and Roland Barthes propositions about the educational potential of narratives.

In his book Pedagogy of Autonomy,7 Paulo Freire emphasizes giving value to the knowledge that students already have from previous experiences, both academic and from everyday life. Freire proposes that the teacher should try to establish an “intimacy” between the curricular knowledge that is considered fundamental for the students’ education and their social experience as individuals. Such an approach has an ethical commitment to recognize and respect the particulars of the students as co-protagonists of the educational process. Teachers are not considered the sole source of a “fundamental knowledge” that has to be transferred into the students, but rather the facilitators of a knowledge construction process in which they must work with the students and not for them. Freire points out that it is indispensable that the future teacher, since his/her formative years, understands and persuades him/herself that to teach is not to transfer knowledge but to create the possibilities for the production or construction of knowledge.

Carmen Neves, educator and former Secretary of Distance Learning (Seed) for the Brazilian Ministry of Education, drew on her many experiences to theorize a “pedagogy of authorship.” The pedagogy of authorship seeks to appropriate different forms of media for content creation through collaborative work among teachers and students. Neves proposes that the pedagogy of authorship “stimulates the integrated use of multiple forms of language (visual, written, musical etc.)”8 and promotes authorship and respect for plurality and collective construction, recognizing teachers, students and school managers as active subjects instead of passive ones. She proposes a 3-step process: exploration, experimentation and expression. Exploration is the search for information in different sources: books; TV; web, etc. Experimentation is the work done with the collected information (comparing, analyzing, debating with colleagues, extrapolation, etc.) Expression is authorship, i.e., creating from the information collected and analyzed.

The pedagogy of authorship does not intend to transfer the responsibility of the educational process solely to the students. It does wish to stimulate autonomy, creativity and the search for knowledge in the students, but the teachers are always present in the process working with the students.

Pedagogy of autonomy and pedagogy of authorship intend to motivate students and teachers to think critically and produce creatively. Our goal with Didactic Ludonarrative is to have the students present a production about what they have experienced (existing knowledge) and then move to present a creation based on what they have experienced but offers something new, thus creative! (new knowledge)

To organize the expected productions of the participants, we follow the example of work projects by Fernando Hernandez,9, who uses the word “project” with the same meaning that architects, designers and artists use: “the work procedure that involves the process of giving form to an idea that is in the horizon, but that admits modifications, that is in permanent dialogue with the context, with the circumstances and with the individuals who, in one way or another, will contribute to this process.”10 Therefore, we use a project method to guide the configuration of the expected production from the participants.

The ludic or game aspect comes from a Game Based Learning (GBL) perspective. Kevin Corbett, former science teacher and specialist in e-learning proposes the following definition of GBL:

[GBL] is a branch of serious games that deals with defined learning outcomes. They’re called Serious Games because instead of providing only entertainment, they have an educational goal to provide retention of a skill or concept that can be applied in the real world.11

Corbett explains that in games “failing” not only is allowed but also can be considered an expected part of the process. In games, a player can have second chances, multiple lives, and different paths to succeed. Games also require concentrated attention, thus developing focus. Feedback is constant and in real time, which constitutes an important element of learning. He points out that most games have a context-specific story, that is an important factor to attract and engage players, and that games can be fun.

The study conducted by the UK-based National Foundation for Educational Research on the effectiveness of Game Based Learning points out a series of principles and mechanisms of GBL.12 Yet we disagree with their definition that refers only to videogames to support teaching and learning.13 But we consider their list of principles and mechanisms applicable to Didactic Ludonarrative since they also point out to the principles of learning by fun while doing, autonomy, and the mechanisms of rules, clear goals, student agency, immediate and constructive feedback, the social element of sharing experiences and a fictional setting.

For the narrative aspect, we referred to the work of Roland Barthes.14 He argues that literature, and by extension all forms of narrative, have the powers of mathesis (many types of knowledge interweaving themselves) and mimesis (representation of reality), stressing its educational potential. Narratives allow the ludic meeting of several forms of knowledge in their production and reception, legitimating multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary work. For example, one can find in Daniel Defoe’s romance Robinson Crusoe (1719) different “teachable” elements: History, Social Geography (colonialism), Technology (building a house, creating tools), Anthropology and others. In a narrative, many forms of knowledge can coexist and, as he puts it, be “spun and savored.” That is mathesis. In its mimetic power the narrative can represent reality and make the applications of a concept or technique clearer for the student, thus answering a lingering question that anguishes many students: Why am I learning this? Barthesian mimesis has an answer, for it aims at a creative representation of reality that goes beyond its mere reproduction. The mimesis of Barthes does not limit itself at showing reality how it is (which it considers to be an impossible goal), but rather aims at showing how reality may yet be, assuming, therefore, a poetic commitment. Our students are our future poets.

In participatory narratives such as RPGs, the “movement” of the story occurs due to the decisions of the participants about the actions of their characters who are the protagonists of the story. Participatory narratives, as Janet Murray points out,15 engage us in a different way because they become “ours” – that story unfolded the way it did due to our decisions as readers or participants. When this participation is mediated through rules, such as in choose-your-own-adventure gamebooks (hereafter referred to as “gamebooks”) and RPGs, we have a convergence of game and narrative, a ludonarrative.

Therefore, we would like to propose a third Barthesian power for participatory narratives: dynamis. This power allows the participants to perceive that their actions bring consequences and, in the case of RPG, recreations of the plot. We believe that dynamis resonates with the GBL principles of “autonomy,” “learn by fun,” and the mechanisms of “clear goals,” “rules,” “student control,” “immediate and constructive feedback,” “fictional setting,” and, in the case of RPG, “social elements.” Dynamis permits a participant to have a similar experience to “dramatic agency” proposed by Murray, even though the play may not occur in a digital environment:

DRAMATIC AGENCY – The experience of agency within a procedural and participatory environment that makes use of compelling story elements, such as an adventure game or an interactive narrative. To create dramatic agency the designer must create transparent interaction conventions (like clicking on the image of a garment to put it on the player’s avatar) and map them onto actions which suggest rich story possibilities (like donning a magic cloak and suddenly becoming invisible) within clear stories with dramatically focused episodes (such as, an opportunity to spy on enemy conspirators in a fantasy role playing game).16

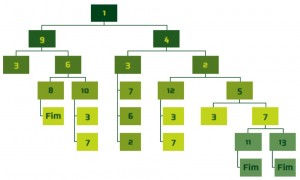

In our work we currently use gamebooks and tabletop RPGs. Gamebooks are choose-your-own-adventure stories in which the reader has to decide the path followed by the main character during certain key moments. Therefore, the reader is allowed to choose among preset alternatives. It can be considered a first step to motivate the development –– or reawakening –– of autonomy for the students. Using rules to determine the outcome of certain events not only brings gaming into the classroom, but the game design can promote learning goals. We present below the structure of story events of two gamebooks designed by us. The first was used to help deaf students (6-7 years old) to acquire written and oral Portuguese and sign language (Zoo). The second is being used for 5th year students (11 year old) in Brazil´s National Strategy for Financial Education (Enef)

Zoo

Tabletop RPGs were used as a follow-up with the students in the second experience where they played with the same characters in the same fictional setting used in the first gamebook.

The Experiences

Let us now discuss two experiences created by our research group. The first experience was conducted with bachelor degree students at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF). The second experience happened in a private school with students of the 4th year of the Fundamental level (10-11 years old) students. In both experiences, the same university teachers were involved, as well as bachelor students who are members of our research group, most of which are studying to pursue a career as teachers themselves.

The First Experience – Bachelor Degree Students at UFJF

The first experience was conducted throughout 2013, involving twelve students and two university professors. All the participants were members of our research group.

The goal was to use the Incorporeal RPG17 to help students to develop their competencies of Creativity, Ethics and Management for the production of illustrations. Competencies are here understood as mental operations through which a person articulates and mobilizes skills, knowledge and attitude to solve a challenge.18

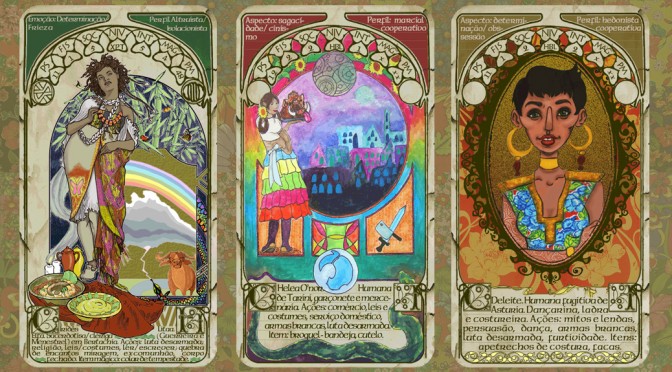

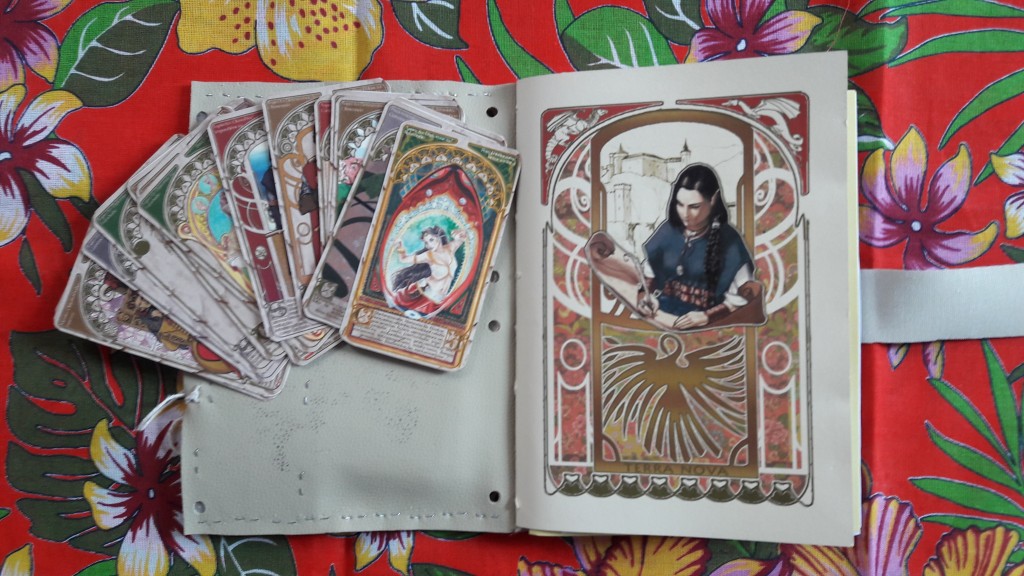

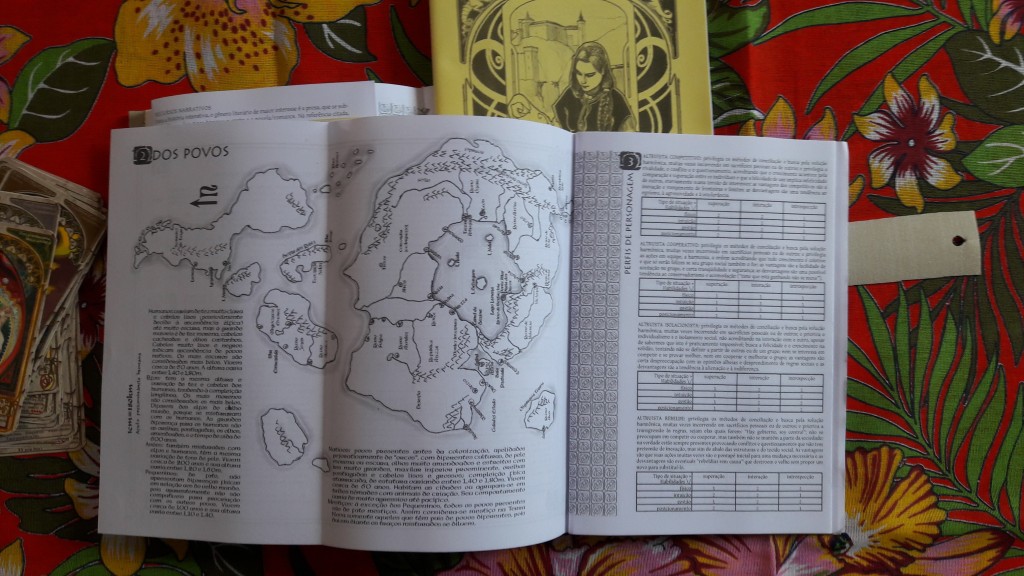

The RPG scenario used was one of medieval fantasy with an Art Noveau-inspired visual structure. A narrative and visual mixture that we named “Anthropophagic Pillage” in a combination of the strategies of “Narrative Pillage” and “Visual Anthropophagi”. Narrative Pillage consists in acts of appropriation of personal references and of other sources to create one´s character and other narrative elements.19 Visual Anthropophagi brings the proposals of contamination of the colonizer by the colonized as stated in the Anthropophagic Manifesto – a Brazilian artistic movement of the early 20th century. Based on these conceptual premises our students needed to combine their personal repertoires with Brazilian and non-Anglo-Saxon Art and Literature references.

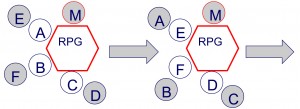

To accommodate larger groups each character was played in duo with a player and a “conscience”. The player controlled the character while the conscience wrote down the events and gave advice. Therefore a group of five player-characters actually involved ten students. There were several RPG sessions in which the students switched the roles of “player” and “conscience”. So each player would be the conscience for the other player´s character. One teacher (M) acted as the Game Master in all sessions.

Figure 2: The structures of RPG play sessions and post production.

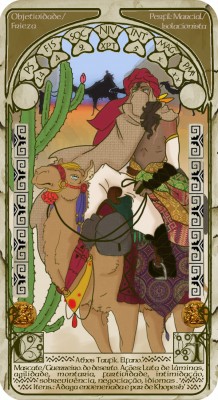

Afterwards, the students made conceptual illustrations as a preparation to create a final illustration for a card to incorporate their characters into a “RPG deck of characters”. They also created stories regarding places of the scenario and their characters. This was their final production. The students registered the steps of their production process in “journals” or sketchbooks. The first RPG experiences occurred from December 2012 to March 2013.

Besides the weekly face-to-face sessions the experiment also had the support of a Moodle platform for distance-learning where texts, images and references were made available.

This first experiment was conducted in the following steps:

- Contextualization: students read the setting concept in the Moodle Virtual Learning Environment (AVA) available to them. Then they proceeded to:

- Create their characters and play RPG sessions in the “Terra Nova” setting.

- Register through handwritten or virtual diaries the story of their characters and the events experienced during the adventures.

- Materialize the characters and their context through concept arts registered in personalized sketchbooks.

- Research: activity in a forum format in the AVA with links available for research. They had to:

- Based on the concept of their character, the students should research visual styles that they would like to “cannibalize” and “mestizise”20 with the Art Nouveau style.

- Make an iconographic research of places and cultures that they find interesting to mix with the background and context of their characters.

- Conception: activities of production that had to be presented through online posting of files and face to face presentation of the sketchbooks from January 11th of 2013 to March 22nd of 2013.

After a brief recess due to university activities, we resumed the research project from July to October of 2013. This time we had to include another goal: the creation of materials for an academic event called SEMAD. We organized the previous production of the students (concept art, text, sketchbooks) to extract a visual identity for a deck of character cards and non digital notebooks. This activity was registered in the AVA.

The students’ production finished with the elaboration of the final arts of their characters that became a part of the Terra Nova characters deck card that was posted in the setting blog: http://historias.interativas.nom.br/terranova/2-das-personagens-e-seus-feitos/

We assembled 14 Terra Nova RPG books, 2 for game masters (GM) and 12 for players, size A5 (closed), using black and white printing over offset 75g paper. These RPG books can be seen at:

http://historias.interativas.nom.br/terranova/caderno-e-encartes/

Finally, the results obtained by the students were evaluated considering innovative recombination (Creativity), critical thinking (Ethics) and consistency (Management) in the use of visual and narrative repertoires.

Analyzing the First Experience

Our analysis revealed that a process of research and combination of different repertoires was indeed used by the students in the elaboration of the materials that they presented.

Through interviews with the students, we verified that they considered the experiment engaging and that it had propelled the development of the competencies in question, leading to the creation of interesting illustrations. We reached the same conclusion. Here follows a summary of the interviews´ results with six students (A, B, C, D, E and F).

(A): felt the need to research to refine her character. Her brother (6th year Fundamental level, 12 years old) researched Geography and Mythology with her, including content that he was studying at school classes at that time. The little brother´s goal was to help her to elaborate a map of Terra Nova.

(B) and (C): it made a difference for them to have affection and fun as motivators to research things that otherwise they would never have researched.

(D) and (A): worked with personal and psychological questions in their production.

(D): the first version of his character was, in his view, “bureaucratic”, but when he worked with his desires and wishes, the relation with the character became pleasant and interesting. The method made it easier for him to draw from references, something that he did not like to do. He liked to be able to change and add things to his character as the narrative progressed through RPG sessions. He wished that the “consciences” could have participated more in the narrative itself. He missed seeing the production of the other students and felt that they could have produced more.

(E): felt that researching contemporary things to mix with Fantasy was very enjoyable.

(F): created a character based on the fact that he was a beginner as a RPG player and transferred that feeling by creating a character that was an inexperienced person. He researched the setting and made a connection with the Brazil´s state of Bahia in the northeast. He chose as a stylistic reference the color pallet of the illustrator Lisa Frank.

The production of the students was analyzed through what we called the “Anthropophagic Test.” We concentrated the analysis in the final art of the cards for the characters´ deck that were produced by the students. Two people produced written texts. The categories for the analysis were:

Visual anthropophagi: recombination of iconographic and stylistic repertoires of the setting with iconographic and stylistic repertoires that the participant mobilized and/or appropriated.

Narrative pillage: recombination of narrative repertoires of the setting with narrative repertoires that the participant mobilized and/or appropriated.

The production was analyzed in a group meeting with the students where all could give their assessment and opinions on each other’s production. The following questions were used as guidelines:

- Were there a mobilization and/or appropriation of visual styles other than the base style (art nouveau)? Which ones?

- Does the visual style of the presented card satisfactorily present the concept of the setting?

- Were there a mobilization and/or appropriation of iconography that not only the available iconography based on Tolkien´s work? Which ones?

- Does the iconography of the cart presented satisfactorily describe the concept of the character?

Our analysis showed that there was indeed a process of research and combination of different repertoires by the students in the elaboration of the materials presented by them in different narrative supports. After the test results some of the students remade their cards, as can be seen in Figure 3.

| Character card presented before the test | Character card presented after the test |

|

|

Figure 3: character created by one student that she opted to change after the anthropophagic test.

The activity brought a productive alternative to expositive classes. It is currently being used in the Illustration course of the first cycle of the Interdisciplinary Bachelor Program in Arts and Design of UFJF and was also used in the Ludonarrative Workshop for future Visual Art Teachers for the second cycle of the IAD-UFJF.

Analyzing the Second Experience

The second experience happened from October to November of 2014 with 36 students of 2 classes of the 4th year of Fundamental School and had the collaboration of 2 school teachers, the professors and 5 bachelor degree students of the first experiment.

The briefing session with the school teachers determined that the main competencies to be developed by their students were “focus” and “teamwork”. It was also necessary to work with topics of History and Geography. Plus, the school in question applies a “project approach” using the students´ current interests to motivate them. In that semester the project was Greek Mythology” due to the students´ interest in fictional works in that area. All these aspects were taken into consideration to elaborate the activity. The RPG scenario used was a contemporary one with a magic and a focus on Sustainability.

The experiment was done using two regular school classes in which the two groups of students were organized in one classroom under the supervision of their teachers. In the first session, the students played a gamebook that helped them to create their characters. The decisions made while reading the gamebook led to conclusions with different character profiles: Greek demigod or magical being from Brazilian folklore. The kids played the gamebook in pairs and at the end of it they created their characters together.

Three weeks later the students had their RPG session. They were organized in three groups of 12 participants. Each character was controlled by a duo, again a player and a conscience. One professor and two college students acted as GameMasters. After the RPG adventure the students were required to present a textual and visual production.

The topics of History and Geography were a part of the plots of the gamebook and the RPG session, the competencies of focus and teamwork were developed through the activities involved in these participative narratives.

The results of the experiment were evaluated using the techniques of participant observation and semi structured interviews with teachers and students. Two weeks later, the teachers were interviewed again and reported that the impact of the experiment had been very positive both in the learning of the topics and the development of the competencies by the students based on their observations of them and evaluation their production. As a result, the school requested that the experiment continue and expand to other classes in 2015.

A “Special Event”

The first experience was considered very satisfactory. The results for the second experience were not so satisfactory for us, as we haven´t yet received the production of the Fundamental Level students from their teachers. Also, some of the follow-up tasks that we proposed for the students were not done due to a lack of time in their part. Overall, we came with the impression that our ludonarrative activities became a “special event” but not really integrated into the school activities and therefore may not have the lasting effects in terms of attitude that we hoped for, although they did help with focus and content absorption. Since we will be working with the same group, now as 5th year students, we intend to research these matters further. We would like to encourage debate with other educators and researchers interested in the educational possibilities of tabletop RPG for classroom students.

–––

Featured Photo by Eliane Bettocchi

–––

Eliane “Lilith” Bettocchi is a professor at the Arts and Design Institute of the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF) in Brazil. Between 1991 and 2010, she was an illustrator, game designer and art director for Brazilian publishers. She also had illustrations published by US gaming companies such as Green Ronin, GenCon and Hidden City.